The dissipation of a mushroom cloud, a distinctive pyrocumulus cloud formed by a large explosion, particularly nuclear detonations, is a complex process influenced by various factors such as the size of the explosion, atmospheric conditions, and the surrounding environment. Typically, the initial visible cloud can rise rapidly, reaching its maximum height within minutes, but the complete dispersal of radioactive particles and gases can take significantly longer, ranging from hours to days or even weeks, depending on weather patterns and the nature of the explosion. Understanding this timeline is crucial for assessing the immediate and long-term impacts of such events on human health, the environment, and emergency response strategies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Factors affecting dissipation time (wind, humidity, explosion size, atmospheric conditions, particulate matter)

- Initial rise and stabilization (mushroom cloud formation, stem rise, cap expansion, stabilization height)

- Radioactive decay and fallout (fission products, radioactive isotopes, fallout patterns, decay rates, contamination spread)

- Atmospheric dispersion models (Gaussian models, Lagrangian models, Eulerian models, particle dispersion simulations)

- Environmental and health impacts (radiation exposure, thermal radiation, blast effects, long-term health consequences, ecological damage)

Factors affecting dissipation time (wind, humidity, explosion size, atmospheric conditions, particulate matter)

The dissipation time of a mushroom cloud is influenced by several key factors, each playing a critical role in how quickly the cloud disperses. Wind is one of the most significant factors, as it directly affects the movement and dispersal of the cloud. Strong, consistent winds can rapidly break apart the cloud and distribute its particles over a wide area, significantly reducing dissipation time. Conversely, calm or variable wind conditions can cause the cloud to linger longer, as the lack of consistent airflow hinders effective dispersal. Wind direction also matters; if winds carry the cloud away from populated areas, dissipation may appear faster due to reduced visibility, even if the particles remain suspended in the atmosphere.

Humidity levels in the atmosphere also impact dissipation time. High humidity can cause water vapor to condense around particulate matter in the cloud, increasing the mass of the particles and causing them to fall out of the atmosphere more quickly. This process, known as wet deposition, accelerates the dissipation of the lower portions of the mushroom cloud. However, in dry conditions, particles remain lighter and can stay suspended longer, prolonging the cloud's presence. Humidity also affects the chemical reactions occurring within the cloud, potentially altering the composition and behavior of the particulate matter.

The size of the explosion is another critical factor, as it determines the initial volume and density of the mushroom cloud. Larger explosions produce more particulate matter and energy, resulting in a taller, denser cloud that takes longer to dissipate. The greater mass of particles requires more time for atmospheric forces to disperse or settle them. Additionally, larger explosions often inject particles higher into the atmosphere, where they can remain suspended for extended periods due to reduced gravitational influence and stronger wind currents.

Atmospheric conditions, including temperature gradients and air stability, further influence dissipation time. In unstable atmospheric conditions, such as those with warm air rising rapidly, the cloud can be lifted higher and dispersed more quickly. Conversely, stable conditions, where air layers resist vertical movement, can trap the cloud closer to the ground, prolonging its visibility and presence. Temperature inversions, where warmer air sits above cooler air, can also act as a lid, preventing the cloud from rising and causing it to persist longer at lower altitudes.

Finally, the nature of the particulate matter within the cloud plays a crucial role in dissipation time. Larger, heavier particles, such as debris from the explosion, tend to settle out of the atmosphere more quickly due to gravity. In contrast, finer particles, like radioactive isotopes or ash, can remain suspended for much longer periods, especially if they are lightweight and resistant to aggregation. The chemical composition of the particles also matters; some materials may react with atmospheric components, altering their size, weight, or behavior and thus affecting how long they remain in the cloud. Understanding these factors collectively provides insight into the complex process of mushroom cloud dissipation.

Perfectly Sautéed Shiitake Mushrooms: Timing Tips for Optimal Flavor

You may want to see also

Initial rise and stabilization (mushroom cloud formation, stem rise, cap expansion, stabilization height)

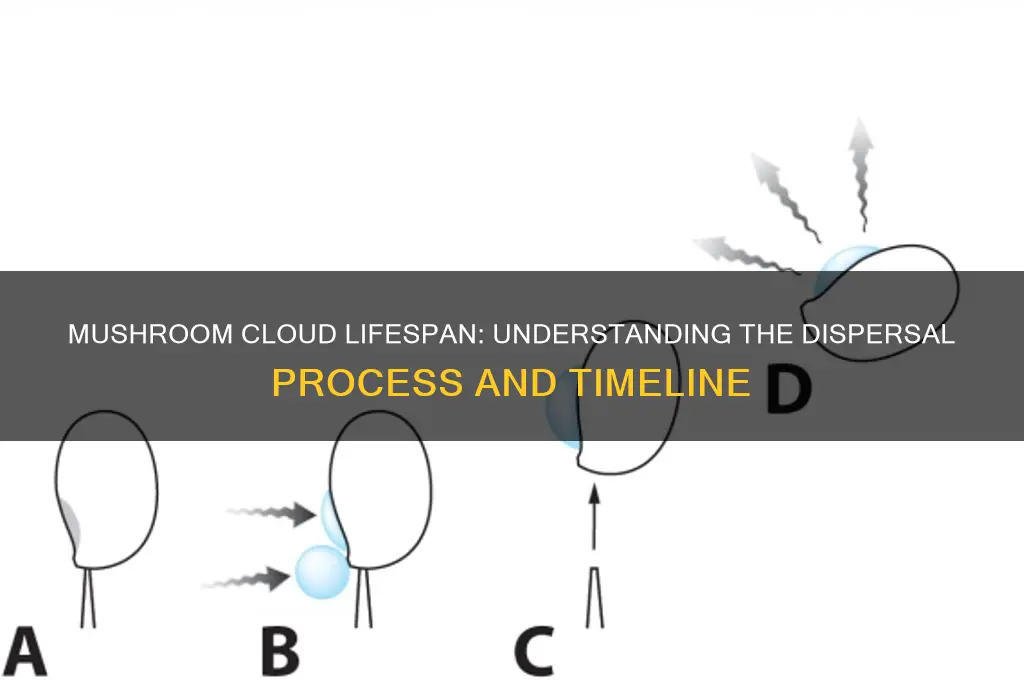

The initial rise and stabilization of a mushroom cloud is a complex and dynamic process that occurs within the first few minutes after a nuclear explosion. As the fireball touches the ground, it creates a massive upward rush of hot gases, dust, and debris, marking the beginning of the mushroom cloud formation. This phase is characterized by the rapid ascent of the cloud's stem, which can reach several thousand feet in the first 10 to 20 seconds. The stem's rise is fueled by the intense heat and pressure generated by the explosion, causing the air to expand and rise at incredible speeds.

As the stem continues to rise, it begins to cool and spread out, leading to the expansion of the cloud's cap. This cap expansion occurs as the hot gases and debris mix with the surrounding air, causing the cloud to flatten and widen. The cap's growth is influenced by atmospheric conditions, such as wind speed, humidity, and temperature, which can affect the rate and direction of its expansion. Typically, the cap will expand to a diameter of several miles within the first 1 to 2 minutes after the explosion. During this stage, the cloud's shape starts to resemble the classic mushroom form, with a distinct stem and a broad, flattened cap.

The stem rise and cap expansion are followed by a period of stabilization, where the cloud reaches its maximum height and begins to settle. The stabilization height is determined by the balance between the upward momentum of the hot gases and the downward pull of gravity. This height can vary depending on the yield of the explosion and atmospheric conditions, but it generally occurs between 30,000 and 50,000 feet above the ground. At this point, the cloud's ascent slows down significantly, and its shape becomes more defined, with a well-formed stem and a fully expanded cap.

During the stabilization phase, the mushroom cloud starts to interact with the surrounding atmosphere, leading to the formation of complex flow patterns and vortices. These interactions can cause the cloud to distort and change shape, but its overall structure remains relatively stable. The stabilization height is a critical factor in determining the subsequent behavior of the cloud, including its dissipation rate and the potential for fallout. As the cloud stabilizes, it begins to cool and mix with the surrounding air, setting the stage for the eventual dissipation of its components.

The initial rise and stabilization process typically lasts for about 5 to 10 minutes, after which the mushroom cloud enters a more gradual dissipation phase. The exact duration of this process depends on various factors, including the explosion's yield, atmospheric conditions, and the cloud's initial composition. However, by understanding the key stages of initial rise and stabilization – mushroom cloud formation, stem rise, cap expansion, and stabilization height – we can gain valuable insights into the behavior and lifespan of these iconic yet devastating phenomena. This knowledge is essential for assessing the potential impacts of nuclear explosions and developing strategies to mitigate their effects.

Safely Storing Morel Mushrooms: Optimal Refrigeration Time and Tips

You may want to see also

Radioactive decay and fallout (fission products, radioactive isotopes, fallout patterns, decay rates, contamination spread)

Radioactive decay and fallout are critical components in understanding how long a mushroom cloud persists and the subsequent environmental and health impacts. When a nuclear explosion occurs, it generates a vast array of fission products—radioactive isotopes created by the splitting of atomic nuclei. These isotopes, such as iodine-131, cesium-137, and strontium-90, are released into the atmosphere as part of the mushroom cloud. Each isotope has a unique decay rate, measured by its half-life, which determines how quickly it loses radioactivity. For instance, iodine-131 has a half-life of about 8 days, while cesium-137 decays over approximately 30 years. These decay rates influence how long the radioactive materials remain hazardous and how they contribute to fallout.

Fallout patterns are shaped by the size of the explosion, weather conditions, and the altitude of the detonation. Larger particles settle quickly near the blast site, while smaller particles can remain suspended in the atmosphere, traveling long distances before returning to the ground. This process creates a fallout pattern that can contaminate areas far beyond the immediate explosion zone. The spread of contamination depends on wind currents, precipitation, and the physical properties of the radioactive particles. For example, rain can wash radioactive materials out of the air, leading to localized "hot spots" of contamination.

The dissipation of a mushroom cloud itself is relatively rapid, typically within minutes to hours, as the hot gases cool and disperse. However, the radioactive fallout persists much longer, driven by the decay rates of the isotopes involved. Short-lived isotopes like iodine-131 decay quickly, reducing their impact within weeks, but long-lived isotopes like cesium-137 and strontium-90 can contaminate environments for decades. This extended contamination poses risks to human health, agriculture, and ecosystems, as these isotopes can accumulate in soil, water, and the food chain.

Understanding decay rates is essential for assessing the long-term effects of fallout. Isotopes with longer half-lives continue to emit radiation for extended periods, increasing the cumulative dose to exposed populations. For instance, cesium-137 can remain in the environment for centuries, gradually decaying and posing a persistent threat. Monitoring and managing contaminated areas require knowledge of these decay rates to predict when radiation levels will decrease to safer thresholds.

Finally, the spread of contamination is influenced by both physical and environmental factors. Soil type, vegetation, and human activities can affect how radioactive materials are distributed and absorbed. In areas with high rainfall, isotopes may leach into groundwater, while in arid regions, they may remain on the surface. Effective mitigation strategies, such as decontamination and land-use restrictions, depend on a clear understanding of fallout patterns and decay rates. By studying these processes, scientists and policymakers can better address the challenges posed by radioactive fallout and its long-term impacts.

Perfectly Cooked Stuffed Mushrooms: Timing Tips for Delicious Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Atmospheric dispersion models (Gaussian models, Lagrangian models, Eulerian models, particle dispersion simulations)

Atmospheric dispersion models are essential tools for predicting how pollutants, including the components of a mushroom cloud, spread and dissipate in the atmosphere. These models simulate the transport, diffusion, and transformation of substances released into the air, providing insights into their concentration over time and space. Among the most widely used models are Gaussian models, Lagrangian models, Eulerian models, and particle dispersion simulations, each with distinct methodologies and applications. Understanding these models is crucial for estimating how long a mushroom cloud, which consists of debris, radioactive particles, and gases, will persist in the atmosphere.

Gaussian models are among the simplest and most traditional atmospheric dispersion models. They assume that pollutants disperse in a Gaussian (bell curve) distribution perpendicular to the wind direction. These models rely on parameters such as wind speed, stability of the atmosphere, and the height of the emission source. While Gaussian models are computationally efficient and widely used for short-range predictions, they have limitations in complex terrains or for long-range dispersion. For a mushroom cloud, Gaussian models can provide initial estimates of downwind concentration but may not fully capture the vertical mixing or chemical transformations of radioactive particles.

Lagrangian models take a particle-based approach, tracking the movement of individual "parcels" of air as they disperse in the atmosphere. Each parcel is influenced by wind fields, turbulence, and other meteorological factors. Lagrangian models are particularly effective for simulating long-range transport and complex atmospheric conditions, making them suitable for analyzing the dispersion of mushroom cloud components over large areas. However, their computational intensity can be a drawback for real-time applications. These models can provide detailed predictions of how radioactive particles spread and dilute over time, contributing to estimates of dissipation rates.

Eulerian models divide the atmosphere into a fixed grid and solve equations for pollutant concentration within each grid cell. This approach is advantageous for simulating dispersion in highly complex or urban environments, where interactions between the ground and atmosphere are significant. Eulerian models are often used for regional or global-scale predictions and can account for chemical reactions and deposition processes. For a mushroom cloud, Eulerian models can simulate the gradual settling of heavier particles and the chemical breakdown of gases, offering insights into the cloud's dissipation timeline. However, their high computational demands and grid-based resolution can limit their use for fine-scale analyses.

Particle dispersion simulations combine elements of Lagrangian and Eulerian models, tracking individual particles while considering grid-based atmospheric conditions. These simulations are highly versatile and can incorporate detailed physics, such as particle size, density, and chemical properties. For a mushroom cloud, particle dispersion simulations can model the behavior of specific components, such as radioactive isotopes or debris, as they disperse and interact with the environment. This level of detail allows for precise predictions of how long different parts of the cloud will remain airborne and how they will eventually dissipate through deposition or decay.

In summary, atmospheric dispersion models—Gaussian, Lagrangian, Eulerian, and particle-based—each offer unique advantages for predicting the dissipation of a mushroom cloud. Gaussian models provide quick estimates, Lagrangian models excel in long-range transport, Eulerian models handle complex environments, and particle simulations offer detailed component tracking. By applying these models, scientists can estimate the time it takes for a mushroom cloud to dissipate, considering factors like wind patterns, atmospheric stability, and the physical properties of the released materials. This knowledge is vital for assessing the environmental and health impacts of such events.

Perfect Soaking Time for Wood Ear Mushrooms: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Environmental and health impacts (radiation exposure, thermal radiation, blast effects, long-term health consequences, ecological damage)

The dissipation of a mushroom cloud, a visible indicator of a nuclear explosion, is a complex process that varies depending on factors like the yield of the explosion, weather conditions, and altitude. However, the environmental and health impacts of such an event extend far beyond the cloud's disappearance, often persisting for decades. Radiation exposure is one of the most immediate and severe consequences. During a nuclear detonation, intense gamma and neutron radiation are released, which can cause acute radiation syndrome (ARS) in individuals within a few kilometers of the blast. This radiation also contaminates the surrounding area, creating a hazardous environment that can last for years. Radioactive fallout, consisting of particles carried by the mushroom cloud, can spread over vast distances, exposing populations to prolonged low-dose radiation, which increases the risk of cancer, genetic mutations, and other long-term health issues.

Thermal radiation from a nuclear explosion is another critical concern. The blast emits a massive amount of infrared and visible light, capable of causing severe burns and igniting fires across a wide area. These fires can merge into a firestorm, further spreading radioactive particles and exacerbating ecological damage. The heat can also destroy vegetation, wildlife habitats, and infrastructure, leaving long-lasting scars on the landscape. For humans, thermal radiation can lead to immediate fatalities or debilitating injuries, particularly in densely populated areas.

Blast effects contribute significantly to both environmental and health impacts. The shockwave generated by a nuclear explosion can level buildings, uproot trees, and displace large volumes of soil and debris. This physical destruction not only endangers human lives but also disrupts ecosystems, leading to habitat loss and species decline. The blast can also create craters and alter terrain, affecting water drainage and soil stability. In urban areas, the collapse of structures can release hazardous materials, further contaminating the environment and posing risks to survivors.

Long-term health consequences of a nuclear explosion are profound and multifaceted. Beyond the immediate effects of radiation exposure and burns, survivors face increased risks of thyroid disorders, leukemia, and solid cancers due to prolonged exposure to radioactive isotopes like iodine-131 and cesium-137. Psychological impacts, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are also prevalent among affected populations. Additionally, genetic damage caused by radiation can be passed down to future generations, leading to hereditary health issues. Public health systems in affected areas often struggle to cope with the surge in medical needs, exacerbating the long-term suffering.

Ecological damage from a nuclear explosion is extensive and persistent. Radioactive contamination can render land unusable for agriculture, forestry, or habitation for decades. Aquatic ecosystems are equally vulnerable, as radioactive particles can enter water bodies, affecting fish, plants, and other organisms. Biodiversity loss is a common outcome, as species may struggle to adapt to the altered environment. Soil erosion, deforestation, and the destruction of natural habitats further degrade ecosystems, hindering their recovery. Efforts to remediate contaminated areas are costly and time-consuming, often requiring the removal of topsoil, decontamination of water sources, and long-term monitoring.

In summary, while a mushroom cloud may dissipate within hours, the environmental and health impacts of a nuclear explosion endure for generations. Radiation exposure, thermal radiation, blast effects, long-term health consequences, and ecological damage collectively create a devastating legacy that demands comprehensive preparedness, mitigation, and recovery strategies. Understanding these impacts is crucial for policymakers, scientists, and communities to address the far-reaching consequences of nuclear events.

How Long Do Psilocybin Mushrooms Last? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The initial visible mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion typically dissipates within 10 to 30 minutes, depending on atmospheric conditions, altitude of the explosion, and the size of the blast.

While the visible cloud disperses, radioactive particles and debris remain suspended in the atmosphere and can spread over large areas, posing long-term health and environmental risks.

Key factors include wind speed, atmospheric stability, humidity, and the altitude of the explosion. Higher altitudes and unstable atmospheric conditions can cause the cloud to disperse more rapidly.