Fungi are a diverse and widespread group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to forming symbiotic relationships with plants and animals. While estimates vary, scientists believe there are between 2.2 million and 3.8 million fungal species globally, with only about 150,000 formally described and named. This vast diversity includes well-known types such as mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and lichens, each adapted to unique environments and functions. Despite their importance, the majority of fungal species remain undiscovered, highlighting the need for further research to understand their ecological impact and potential applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Classification of Fungi: Fungi are classified into five major phyla based on structure and reproduction

- Common Fungal Types: Includes mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and lichens, each with unique characteristics

- Estimating Fungal Diversity: Scientists estimate over 2.2 million fungal species exist globally

- Edible vs. Toxic Fungi: Some fungi are culinary delights, while others are deadly poisonous

- Fungi in Ecosystems: Fungi play vital roles in decomposition, nutrient cycling, and symbiotic relationships

Classification of Fungi: Fungi are classified into five major phyla based on structure and reproduction

Fungi represent a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, ranging from decomposition to symbiotic relationships. To understand their vast diversity, mycologists classify fungi into five major phyla based on their structural and reproductive characteristics. This classification system provides a framework to organize the estimated 144,000 described species of fungi, with potentially millions more awaiting discovery. The five primary phyla are Chytridiomycota, Zygomycota, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Glomeromycota, each with distinct features that define their ecological and biological roles.

Chytridiomycota, often referred to as chytrids, are the most primitive fungi and are primarily aquatic or found in damp environments. They are characterized by the presence of flagellated spores, a unique feature among fungi. Chytrids reproduce asexually through zoospores and play a significant role in nutrient cycling in aquatic ecosystems. Despite their simplicity, they are ecologically important and include species that can be pathogenic to amphibians.

Zygomycota are known for their ability to form zygospores, thick-walled structures produced during sexual reproduction. These fungi are commonly found in soil and decaying organic matter, where they act as decomposers. Examples include black bread mold (*Rhizopus stolonifer*). Zygomycota typically have coenocytic hyphae (lacking septa) and reproduce both sexually and asexually. However, recent taxonomic revisions have reclassified some members into other phyla, reducing the size of this group.

Ascomycota is the largest fungal phylum, comprising over 70% of described fungal species. Commonly known as sac fungi, they produce spores in sac-like structures called asci. This group includes yeasts, molds, truffles, and morel mushrooms. Ascomycota are incredibly diverse, ranging from unicellular yeasts like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* to filamentous fungi that form symbiotic relationships with plants. Their reproductive strategies and ecological roles make them one of the most successful fungal groups.

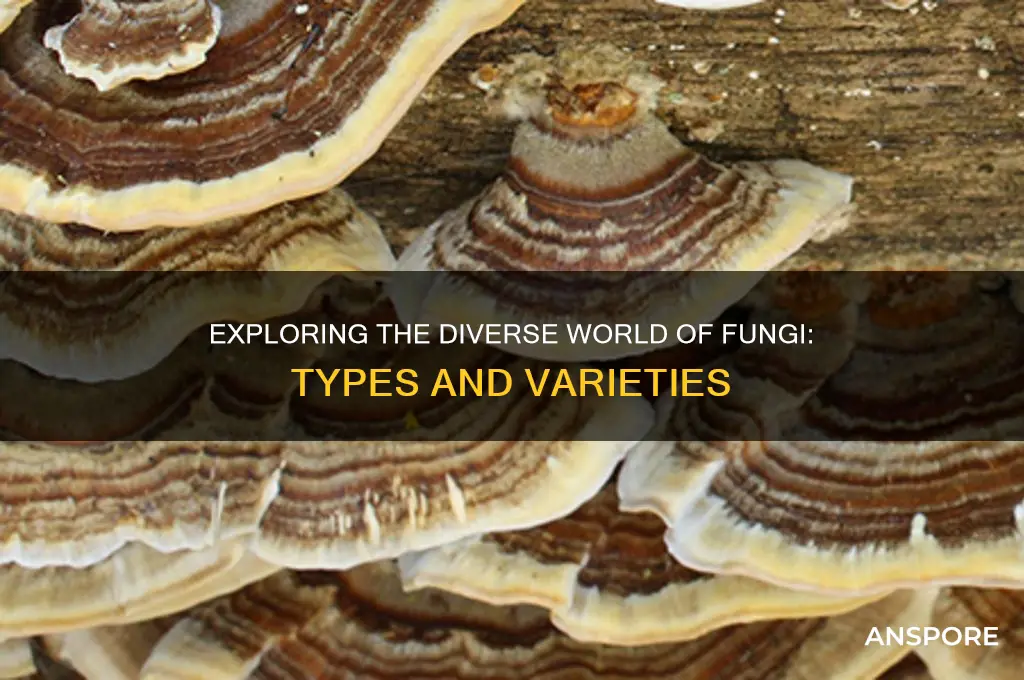

Basidiomycota, or club fungi, are the second-largest phylum and include many familiar mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. They are distinguished by the production of basidiospores on club-shaped structures called basidia. Basidiomycota play critical roles in ecosystems, particularly in wood decomposition and mycorrhizal associations. Examples include the edible button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) and the destructive Dutch elm disease pathogen (*Ophiostoma novo-ulmi*). Their complex life cycles and ecological importance highlight their significance in fungal diversity.

Glomeromycota are primarily known for their symbiotic relationships with plant roots, forming arbuscular mycorrhizae. These fungi lack a true sexual reproductive stage and are characterized by coenocytic hyphae and spore production. Glomeromycota enhance nutrient uptake in plants, particularly phosphorus, and are essential for the health of many ecosystems. Their mutualistic relationships underscore their ecological importance, despite their relatively small number of described species.

In summary, the classification of fungi into these five phyla—Chytridiomycota, Zygomycota, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Glomeromycota—reflects their structural and reproductive diversity. Each phylum contributes uniquely to ecosystems, from decomposition and nutrient cycling to symbiotic relationships with plants and animals. Understanding this classification is essential for appreciating the breadth of fungal diversity and their roles in the natural world.

How to Prevent Wild Mushroom Killers

You may want to see also

Common Fungal Types: Includes mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and lichens, each with unique characteristics

The fungal kingdom is incredibly diverse, with estimates suggesting there are over 144,000 known species of fungi, though some scientists believe the actual number could exceed 3 million. Among this vast array, certain types are more commonly encountered and studied. Common Fungal Types include mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and lichens, each with distinct characteristics that set them apart. These fungi play vital roles in ecosystems, industries, and even human health, making their understanding essential.

Mushrooms are perhaps the most recognizable fungi, characterized by their fruiting bodies that emerge from the ground or grow on organic matter. They belong to the group Basidiomycetes and Agaricomycetes and are known for their umbrella-like caps and gills or pores underneath. Mushrooms are decomposers, breaking down organic material and recycling nutrients in ecosystems. Some, like the button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), are edible and widely cultivated, while others, such as the death cap (*Amanita phalloides*), are highly toxic. Mushrooms also have medicinal properties, with species like *Ganoderma lucidum* (reishi) used in traditional medicine for their immune-boosting effects.

Yeasts are single-celled fungi primarily classified in the phylum Ascomycota, though some belong to Basidiomycota. Unlike mushrooms, yeasts do not form fruiting bodies and reproduce through budding or fission. They are crucial in fermentation processes, converting sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, which is essential in baking, brewing, and winemaking. *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, commonly known as baker's or brewer's yeast, is a prime example. Yeasts also have industrial applications, such as in the production of biofuels and enzymes. Additionally, some yeasts, like *Candida albicans*, can cause infections in humans, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Molds are multicellular fungi that grow in filamentous structures called hyphae, forming a network known as mycelium. They are primarily found in the phylum Zygomycota and Ascomycota and thrive in damp environments. Molds play a key role in decomposition, breaking down complex organic materials like wood and leaves. Common molds include *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, the latter of which is famous for producing penicillin, a groundbreaking antibiotic. However, molds can also be harmful, causing food spoilage and allergic reactions in humans. Some molds, like *Stachybotrys chartarum* (black mold), produce mycotoxins that pose serious health risks.

Lichens are unique organisms resulting from a symbiotic relationship between fungi (usually Ascomycetes or Basidiomycetes) and photosynthetic partners like algae or cyanobacteria. This partnership allows lichens to survive in extreme environments, from arid deserts to polar regions. Lichens grow slowly and come in various forms, including crustose (crust-like), foliose (leaf-like), and fruticose (branching). They are sensitive to air quality, making them valuable bioindicators of environmental health. Lichens also produce secondary metabolites with medicinal properties, such as usnic acid, which has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects.

In summary, the common fungal types—mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and lichens—each exhibit unique characteristics and play distinct roles in nature and human activities. Understanding these fungi not only highlights their diversity but also underscores their importance in ecosystems, industries, and medicine. As research continues, the fungal kingdom promises to reveal even more fascinating insights into its vast and varied world.

Hillbilly Mushrooms: Nature's Super Strong Superfood

You may want to see also

Estimating Fungal Diversity: Scientists estimate over 2.2 million fungal species exist globally

The question of how many kinds of fungi exist is a fascinating and complex one, with scientists continually refining their estimates as new research emerges. Estimating Fungal Diversity: Scientists estimate over 2.2 million fungal species exist globally, a number that dwarfs the approximately 150,000 species currently described. This staggering figure highlights the vast gap in our knowledge of the fungal kingdom, which plays a critical role in ecosystems as decomposers, symbionts, and pathogens. The 2.2 million estimate is based on advanced statistical models and molecular techniques that account for the hidden diversity of fungi, much of which remains undiscovered due to their microscopic size and cryptic lifestyles.

One of the primary challenges in estimating fungal diversity is the sheer abundance and ubiquity of fungi in nearly every habitat on Earth. From soil and water to plants and animals, fungi are omnipresent yet often invisible to the naked eye. Traditional taxonomic methods, which rely on morphological characteristics, have struggled to keep pace with the diversity of fungal forms. Modern approaches, such as DNA sequencing and metagenomics, have revolutionized the field by uncovering previously undetected species. These techniques have revealed that a single gram of soil can contain hundreds of fungal species, many of which are entirely novel.

The 2.2 million species estimate is not arbitrary but is derived from rigorous scientific analysis. Researchers use tools like high-throughput sequencing to analyze environmental DNA, providing a snapshot of fungal communities in various ecosystems. By extrapolating this data globally and accounting for undersampled regions, scientists arrive at the 2.2 million figure. This estimate also considers the ecological roles of fungi, such as their partnerships with plants (mycorrhizae) and their role in nutrient cycling, which suggest a high degree of specialization and, consequently, species diversity.

Despite these advances, significant uncertainties remain. Tropical regions, for example, are known hotspots of biodiversity but are vastly understudied compared to temperate zones. Additionally, many fungi live in symbiotic relationships with other organisms, and their diversity is often tied to that of their hosts. This interdependence complicates efforts to catalog fungal species independently. Furthermore, the discovery of "dark taxa"—fungi that do not culture easily in labs—has added another layer of complexity to diversity estimates.

In conclusion, Estimating Fungal Diversity: Scientists estimate over 2.2 million fungal species exist globally underscores the immense and largely untapped richness of the fungal kingdom. This estimate is a call to action for increased research and conservation efforts, as fungi are essential for ecosystem health and services. As technology advances and more regions are explored, we can expect this number to be refined, but for now, it stands as a testament to the hidden complexity of life on Earth. Understanding fungal diversity is not just an academic pursuit; it has practical implications for agriculture, medicine, and environmental sustainability.

Mushroom Day: Celebrating Fungi's Unique Number

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.44 $35

Edible vs. Toxic Fungi: Some fungi are culinary delights, while others are deadly poisonous

The world of fungi is astonishingly diverse, with estimates suggesting there are over 140,000 identified species and potentially millions more awaiting discovery. Among this vast array, a critical distinction exists: some fungi are prized for their culinary value, while others are lethally toxic. This duality underscores the importance of accurate identification, as the difference between a delicious meal and a fatal mistake can be subtle. Edible fungi, such as the beloved button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), the earthy porcini (*Boletus edulis*), and the delicate enoki (*Flammulina velutipes*), are staples in cuisines worldwide, celebrated for their unique flavors and textures. These species have been cultivated and foraged for centuries, contributing to both traditional and modern dishes.

In stark contrast, toxic fungi pose a significant risk to humans and animals. Species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) are notorious for their deadly toxins, which can cause severe organ failure and death if ingested. Even experienced foragers can mistake these poisonous species for their edible counterparts, as they often resemble benign varieties. For instance, the Death Cap shares similarities with the edible Paddy Straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*), highlighting the need for meticulous identification. Toxic fungi produce a range of toxins, such as amatoxins and orellanine, which can cause symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress to kidney and liver damage.

The challenge lies in the fact that many edible and toxic fungi belong to the same genera or exhibit similar physical characteristics. For example, the *Amanita* genus includes both the deadly Death Cap and the edible Lion's Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), which are morphologically distinct but underscore the complexity of fungal classification. Additionally, environmental factors such as location, substrate, and season can influence a fungus's appearance, further complicating identification. This ambiguity emphasizes the importance of relying on expert guidance, field guides, and, when in doubt, avoiding consumption altogether.

Despite these risks, the allure of foraging for wild fungi persists, driven by the unique flavors and textures they offer. Edible species like the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) and the Morel (*Morchella* spp.) are highly sought after for their culinary versatility and distinct tastes. However, foragers must exercise caution, as toxic look-alikes such as the False Morel (*Gyromitra* spp.) can cause severe illness if misidentified. Cultivating edible fungi at home or purchasing them from reputable sources is a safer alternative, ensuring both quality and safety.

In conclusion, the distinction between edible and toxic fungi is a critical aspect of understanding the fungal kingdom. While edible species enrich our diets and cultures, toxic varieties demand respect and caution. As our knowledge of fungi expands, so too does our appreciation for their complexity and the need for responsible engagement. Whether you're a chef, forager, or enthusiast, the key to safely enjoying fungi lies in education, vigilance, and a healthy dose of skepticism. After all, in the world of fungi, appearances can be deceiving, and the stakes are often a matter of life and death.

Microdosing Magic Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide

You may want to see also

Fungi in Ecosystems: Fungi play vital roles in decomposition, nutrient cycling, and symbiotic relationships

Fungi are an incredibly diverse group of organisms, with estimates suggesting there are between 2.2 million and 3.8 million species globally, though only about 150,000 have been formally described. This vast diversity underscores their importance in ecosystems, where they perform critical functions such as decomposition, nutrient cycling, and forming symbiotic relationships. Among the most well-known types of fungi are mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and lichens, each adapted to specific ecological niches. Despite their variety, all fungi share a common role as nature’s recyclers, breaking down organic matter and returning essential nutrients to the soil.

In decomposition, fungi are primary decomposers, particularly of complex materials like lignin and cellulose found in plant matter. Unlike bacteria, which struggle with these tough compounds, fungi secrete enzymes that efficiently break them down. This process releases nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus back into the ecosystem, making them available to other organisms. Without fungi, dead organic material would accumulate, stifling nutrient flow and disrupting ecosystem productivity. Their decomposing activity is especially vital in forests, where they help maintain soil fertility and support plant growth.

Fungi are also key players in nutrient cycling, forming extensive underground networks called mycorrhizae. These symbiotic associations between fungal hyphae and plant roots enhance the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. In exchange, the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. Mycorrhizal networks can connect multiple plants, facilitating nutrient transfer between them and promoting overall ecosystem resilience. This relationship is so widespread that over 90% of plant species are estimated to form mycorrhizal associations with fungi.

Beyond nutrient cycling, fungi engage in other symbiotic relationships that shape ecosystems. Lichens, for example, are composite organisms consisting of a fungus and a photosynthetic partner (usually algae or cyanobacteria). Lichens can colonize harsh environments, such as bare rock or Arctic tundra, where they pioneer soil formation and provide food and habitat for other organisms. Additionally, some fungi form mutualistic relationships with insects, such as leafcutter ants, which cultivate fungal gardens as their primary food source. These symbiotic interactions highlight fungi’s adaptability and their role in fostering biodiversity.

The diversity of fungi—estimated in the millions—reflects their evolutionary success and ecological significance. Their roles in decomposition, nutrient cycling, and symbiotic relationships are fundamental to the health and functioning of ecosystems worldwide. From breaking down dead matter to supporting plant growth and enabling life in extreme environments, fungi are unsung heroes of the natural world. Understanding their diversity and functions not only enriches our knowledge of biology but also emphasizes the need to conserve these vital organisms in the face of environmental change.

Trader Joe's Mushrooms: To Wash or Not Before Cooking?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Scientists estimate there are between 2.2 million and 3.8 million species of fungi, but only about 150,000 have been formally described and named so far.

Fungi are broadly classified into seven major groups: Chytridiomycota, Zygomycota, Glomeromycota, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Microsporidia, and Blastocladiomycota. Each group has unique characteristics and ecological roles.

There are approximately 2,000 known edible fungi species and over 1,000 species with documented medicinal properties, though research continues to uncover more.