The structures of ascus and basidium are fundamental to understanding fungal reproduction, particularly in Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, two of the largest fungal phyla. An ascus is a sac-like structure in Ascomycetes that typically contains eight ascospores, though this number can vary depending on the species. In contrast, a basidium in Basidiomycetes usually produces four basidiospores, each located at the tips of sterigmata. These differences in spore production and structure highlight the distinct reproductive strategies of these fungi, influencing their ecological roles, dispersal mechanisms, and taxonomic classification. Understanding the spore counts in these structures provides insights into fungal diversity and their evolutionary adaptations.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ascus Structure and Spore Count: Ascus typically contains 8 spores, arranged linearly within the sac-like structure

- Basidium Spore Production: Basidium usually produces 4 spores, attached externally via sterigmata

- Exceptions in Ascomycetes: Some ascomycetes deviate, producing 1 to thousands of spores per ascus

- Basidiomycete Variations: Rare basidiomycetes may produce 2 or more than 4 spores per basidium

- Ecological Significance: Spore counts influence dispersal, reproduction, and survival in fungi ecosystems

Ascus Structure and Spore Count: Ascus typically contains 8 spores, arranged linearly within the sac-like structure

The ascus, a defining feature of Ascomycota fungi, is a microscopic sac-like structure that serves as the birthplace of spores. Its most striking characteristic is the consistent presence of eight spores, arranged in a linear fashion within its confines. This arrangement is not arbitrary; it reflects the precise cellular divisions that occur during spore development. Each spore, known as an ascospore, is genetically distinct and poised for dispersal, ensuring the fungus’s survival and propagation.

To visualize this, imagine a tiny, elongated pouch under a microscope. Inside, eight spores line up like passengers in a train car, each separated by a thin septum. This linear configuration is a hallmark of ascus morphology and distinguishes it from other fungal structures. The uniformity in spore count and arrangement is a testament to the highly regulated process of sporulation in Ascomycetes. For mycologists and enthusiasts alike, observing this structure offers a window into the intricate reproductive strategies of fungi.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the ascus’s spore count is crucial for identification and classification. For instance, when examining a fungal sample, the presence of an ascus with exactly eight spores immediately narrows the possibilities to the Ascomycota phylum. This knowledge is invaluable in fields like taxonomy, ecology, and even food science, where identifying fungal species is essential for safety and quality control. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a yeast used in baking and brewing, belongs to this group, and its ascus structure can be observed during certain stages of its life cycle.

However, it’s important to note that while eight spores are the norm, exceptions exist. Some Ascomycetes may produce fewer spores due to developmental anomalies or environmental stressors. These variations, though rare, highlight the adaptability of fungi and the need for careful observation. For hobbyists or students studying fungi, using a 40x to 100x magnification microscope is ideal for clearly viewing the ascus and its spore arrangement. Adding a drop of lactophenol cotton blue stain can enhance contrast, making the structure easier to discern.

In summary, the ascus’s eight-spore count is more than just a number—it’s a key diagnostic feature and a marvel of biological precision. Whether you’re a researcher, educator, or curious observer, appreciating this structure deepens your understanding of fungal diversity and the elegance of their reproductive mechanisms. Next time you peer into a microscope, take a moment to admire the orderly lineup of spores within the ascus—a tiny yet profound example of nature’s ingenuity.

Inoculating Mushroom Mycelium with Cold Spores: Risks and Best Practices

You may want to see also

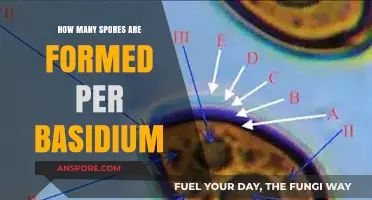

Basidium Spore Production: Basidium usually produces 4 spores, attached externally via sterigmata

In the intricate world of fungal reproduction, the basidium stands out as a master of efficiency, typically producing four spores, each attached externally via delicate structures called sterigmata. This precise arrangement is not merely a coincidence but a testament to the evolutionary refinement of basidiomycetes, a group that includes mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. The sterigmata act as tiny stalks, ensuring that each spore is positioned optimally for dispersal, maximizing the chances of successful colonization in new environments.

Consider the process as a biological assembly line, where the basidium functions as the production hub. As the spores mature, they develop at the tips of the sterigmata, ready to be released upon reaching maturity. This external attachment is crucial, as it allows the spores to be easily dislodged by environmental factors such as wind, water, or even passing animals. For instance, in a forest ecosystem, a single basidium on a mushroom cap can contribute to the dispersal of four spores, each capable of growing into a new mycelium under favorable conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding basidium spore production is essential for mycologists, ecologists, and even gardeners. For example, knowing that each basidium produces four spores can help in estimating fungal populations in a given area. If you observe 100 basidia under a microscope, you can infer the potential release of 400 spores, assuming optimal conditions. This knowledge is particularly useful in studying fungal diseases in crops or in cultivating edible mushrooms, where spore count directly impacts yield.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between basidia and asci, the spore-bearing structures of ascomycetes. While an ascus typically contains eight spores internally, the basidium’s external spore arrangement offers distinct advantages. The external attachment via sterigmata reduces the risk of spores becoming trapped or damaged during release, a common issue in internal spore containment. This difference underscores the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies and their adaptations to various ecological niches.

In conclusion, the basidium’s production of four externally attached spores via sterigmata is a marvel of fungal biology, balancing precision and practicality. Whether you’re a researcher studying fungal ecology or a hobbyist cultivating mushrooms, appreciating this mechanism enhances your understanding of how fungi thrive and spread. By focusing on this specific aspect, you gain insights into the broader role of fungi in ecosystems and their applications in agriculture, medicine, and beyond.

Alcohol's Power: Can 95% Concentration Inactivate Biological Spores?

You may want to see also

Exceptions in Ascomycetes: Some ascomycetes deviate, producing 1 to thousands of spores per ascus

Ascomycetes, a diverse group of fungi, typically produce eight spores per ascus, a sac-like structure where sexual spores develop. However, this rule is not absolute. Some ascomycetes break the mold, producing anywhere from a single spore to thousands within a single ascus. This deviation challenges our understanding of fungal reproduction and highlights the remarkable adaptability of these organisms.

Let's delve into these exceptions, exploring their mechanisms, implications, and the fascinating diversity they represent.

Mechanisms Behind the Deviation:

Several factors contribute to this atypical spore production. Some species, like *Neolecta*, produce only one spore per ascus, a phenomenon known as "monosporic" asci. This could be due to specialized cellular divisions or unique developmental pathways. Conversely, species like *Hypomyces* can produce hundreds or even thousands of spores per ascus, a condition termed "polymorphic" asci. This might involve altered cell wall formation or extended periods of spore maturation within the ascus.

Understanding these mechanisms requires further research into the genetic and environmental factors influencing ascus development.

Implications for Fungal Ecology:

These exceptions have significant ecological implications. Monosporic asci could indicate a strategy for ensuring spore quality over quantity, potentially beneficial in specific environments. Polymorphic asci, on the other hand, might be an adaptation for rapid colonization or dispersal in competitive habitats. Studying these deviations can shed light on the evolutionary pressures shaping fungal reproductive strategies and their role in ecosystem dynamics.

Practical Considerations:

Identifying these exceptions is crucial for accurate fungal identification and classification. Mycologists should be aware of these variations to avoid misidentification. Additionally, understanding these deviations can have applications in biotechnology. For instance, species with high spore production could be valuable for industrial fermentation processes, while those with unique spore characteristics might offer insights into novel biomaterials.

The exceptions in Ascomycetes spore production challenge our assumptions and showcase the incredible diversity within this fungal group. By studying these deviations, we gain a deeper understanding of fungal biology, ecology, and potential applications. From monosporic to polymorphic asci, these variations remind us of the endless surprises the fungal kingdom holds.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Legal in the US? Exploring the Law

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Basidiomycete Variations: Rare basidiomycetes may produce 2 or more than 4 spores per basidium

Fungi in the Basidiomycota division typically produce four spores per basidium, a structure integral to their reproductive cycle. This tetrad pattern is a hallmark of the group, distinguishing them from Ascomycetes, which form spores within an ascus. However, the natural world thrives on exceptions, and rare basidiomycetes challenge this norm by producing two or more than four spores per basidium. These deviations offer a fascinating glimpse into the evolutionary flexibility and diversity within fungal reproductive strategies.

Understanding these variations requires examining the underlying mechanisms. Some species, like certain rust fungi (Pucciniales), produce two spores per basidium, a condition known as bisporidy. This reduction in spore number may be linked to specialized parasitic lifestyles, where efficiency in spore dispersal outweighs the benefits of higher spore counts. Conversely, species producing more than four spores, such as some jelly fungi (Dacrymycetes), exhibit polyspory, a trait possibly tied to their unique ecological niches or evolutionary histories.

From a practical standpoint, identifying these rare basidiomycetes requires careful observation. Look for deviations from the typical four-spored basidium during microscopic examination. Bisporic basidia will appear as pairs, while polysporic basidia may show clusters of six or more spores. Documenting these findings contributes to our understanding of fungal biodiversity and highlights the importance of meticulous field and laboratory work.

For enthusiasts and researchers alike, cultivating these rare species can be rewarding. While specific cultivation techniques vary by species, general principles apply. Maintain sterile conditions to prevent contamination, use appropriate growth media tailored to the species’ nutritional needs, and monitor environmental factors like temperature and humidity closely. Patience is key, as some species may have extended growth cycles.

The study of these variations not only enriches our knowledge of fungal biology but also has broader implications. Understanding how and why these exceptions occur can shed light on evolutionary processes, ecological adaptations, and even potential biotechnological applications. For instance, polysporic species might offer insights into mechanisms of increased spore production, which could be relevant in agricultural or industrial contexts. In conclusion, while the typical basidiomycete produces four spores per basidium, the rare exceptions that produce two or more than four spores provide a window into the remarkable diversity and adaptability of fungi. By studying these variations, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity of life and the endless possibilities within the microbial world.

Pine Trees: Pollen Producers or Spores Carriers? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Ecological Significance: Spore counts influence dispersal, reproduction, and survival in fungi ecosystems

Fungi, often overlooked in ecological discussions, play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships. Central to their life cycles are spores, the microscopic units of dispersal and reproduction. The number of spores produced in an ascus (typically 8 in Ascomycetes) or a basidium (usually 4 in Basidiomycetes) is not arbitrary; it directly influences their ecological success. These counts are finely tuned by evolution to balance energy investment with reproductive output, ensuring fungi thrive in diverse environments.

Consider the ascus, a sac-like structure in Ascomycetes, which typically contains 8 spores. This fixed number is a strategic adaptation. Producing exactly 8 spores minimizes resource expenditure while maximizing dispersal potential. Each spore is a lightweight, resilient vessel capable of traveling vast distances via wind, water, or animals. In nutrient-poor environments, this efficiency is critical. For instance, truffles, prized Ascomycetes, rely on animals to disperse their spores, a process facilitated by their precise spore count and enticing aroma. Without this balance, their survival in forest ecosystems would be compromised.

Basidiomycetes, on the other hand, produce 4 spores per basidium. This lower count reflects a different ecological strategy. Basidiomycetes often form larger, more complex fruiting bodies (like mushrooms) that invest more energy in spore production and dispersal. The reduced number of spores allows for larger individual spores, which can carry more nutrients and genetic material. This is particularly advantageous in competitive environments, such as dense forests, where spores must quickly establish themselves. For example, the iconic Amanita mushrooms use their 4 spores to colonize forest floors, playing a key role in decomposing organic matter and recycling nutrients.

Spore counts also influence fungal survival under stress. In arid or unpredictable climates, fungi with higher spore counts (like certain Ascomycetes) have a better chance of at least one spore finding favorable conditions. Conversely, Basidiomycetes, with fewer but larger spores, are better suited to stable environments where successful germination is more likely. This ecological partitioning ensures that both groups can coexist and contribute uniquely to their ecosystems.

Understanding these spore counts offers practical insights for conservation and agriculture. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, often have specific spore counts that correlate with their host preferences. By manipulating spore dispersal—through controlled burns, soil amendments, or even synthetic spore release—we can enhance forest health and crop yields. Similarly, in fungal restoration projects, knowing the optimal spore count for a given species can improve success rates, ensuring that reintroduced fungi thrive and fulfill their ecological roles.

In summary, the spore counts in asci and basidia are not mere biological curiosities; they are ecological masterstrokes. These numbers dictate how fungi disperse, reproduce, and survive, shaping their interactions with the environment and other organisms. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can better manage ecosystems, harness fungal benefits, and appreciate the intricate ways these organisms sustain life on Earth.

Wandering Trader Spore Blossoms: Can You Obtain Them in Minecraft?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An ascus, the sac-like structure in Ascomycota fungi, typically contains 8 spores.

A basidium, the spore-bearing structure in Basidiomycota fungi, usually produces 4 spores.

The difference in spore count is due to the distinct reproductive mechanisms of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota fungi, with asci undergoing meiosis and mitosis to produce 8 spores, while basidia typically produce 4 spores through meiosis.

Yes, while 8 spores in an ascus and 4 in a basidium are typical, some species may deviate due to genetic or environmental factors.

The number of spores in asci and basidia is a key characteristic used to distinguish between Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, two major fungal phyla.