Zygomycota, a phylum of fungi commonly known as zygomycetes, primarily reproduces through the formation of thick-walled zygospores, which are created when two compatible hyphae fuse during sexual reproduction. This process, known as zygosporangium formation, results in the production of a single, highly resilient spore per zygote. While the exact number of spores produced per reproductive cycle is typically limited to one zygospore, asexual reproduction in Zygomycota can also occur through the release of numerous sporangiospores from sporangia, though these are less durable and serve primarily for rapid dispersal rather than long-term survival. Thus, the reproductive strategy of Zygomycota balances both quality and quantity, ensuring survival in diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Method | Sexual and asexual reproduction |

| Sexual Spores Produced | Zygospores (formed after gametangial fusion) |

| Number of Zygospores per Zygote | Typically one zygospore per zygote |

| Asexual Spores Produced | Sporangiospores (produced within sporangia) |

| Number of Sporangiospores | Hundreds to thousands per sporangium |

| Sporulation Mechanism | Asexual spores are released upon sporangium maturation and rupture |

| Environmental Factors | Sporulation influenced by nutrient availability and environmental cues |

| Role of Zygospores | Serve as dormant, resistant structures for survival in harsh conditions |

| Role of Sporangiospores | Primary means of rapid dispersal and colonization |

| Life Cycle Stage | Zygospores are part of the sexual phase; sporangiospores are asexual |

Explore related products

$9.75 $11.99

What You'll Learn

Sporangiospores production in Zygomycota

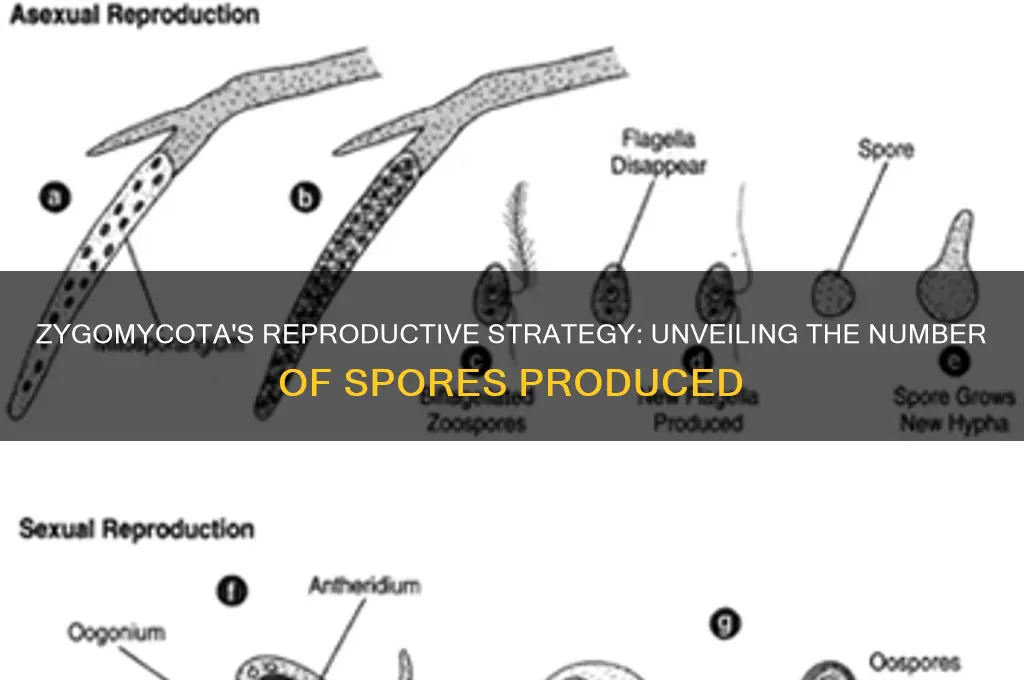

Zygomycota, a diverse group of fungi, primarily reproduces through the formation of sporangiospores, a process that is both efficient and fascinating. These spores are produced within a structure called the sporangium, which develops at the tip of a specialized hyphal branch known as a sporangiophore. The number of sporangiospores produced by Zygomycota can vary widely depending on the species and environmental conditions, but a single sporangium typically contains hundreds to thousands of spores. This high volume ensures that even if a small fraction germinate successfully, the species can effectively propagate.

The production of sporangiospores begins with the maturation of the sporangium, which swells as the spores develop inside. These spores are haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes, and are formed through the process of meiosis followed by mitosis. Once mature, the sporangium wall ruptures or undergoes enzymatic digestion, releasing the spores into the environment. This release mechanism is often facilitated by environmental cues such as changes in humidity or physical disturbance, ensuring dispersal at optimal times.

One of the most intriguing aspects of sporangiospore production is its adaptability. For instance, species like *Rhizopus stolonifer*, commonly known as black bread mold, can produce sporangiospores rapidly under favorable conditions, such as high moisture and warm temperatures. This adaptability allows Zygomycota to thrive in diverse habitats, from soil and decaying organic matter to indoor environments. However, the exact number of spores produced can be influenced by factors such as nutrient availability, pH, and competition from other microorganisms.

Practical considerations for studying or managing Zygomycota include controlling environmental conditions to manipulate spore production. For example, reducing humidity can inhibit sporangium development, while maintaining a consistent temperature range (typically 20–30°C) can promote optimal spore formation. Researchers often use these parameters to cultivate Zygomycota in laboratory settings, allowing for detailed observation of the sporangiospore lifecycle. Additionally, understanding spore production can aid in pest management, as many Zygomycota species are opportunistic pathogens of plants and stored foods.

In conclusion, sporangiospore production in Zygomycota is a highly efficient reproductive strategy characterized by its volume and adaptability. While the exact number of spores produced varies, the process is finely tuned to environmental cues, ensuring successful dispersal and colonization. By studying this mechanism, scientists gain insights into fungal ecology and develop practical applications for agriculture, food preservation, and biotechnology. Whether in a laboratory or natural setting, the production of sporangiospores remains a cornerstone of Zygomycota’s survival and proliferation.

Can Mold Spores Penetrate N95 Masks? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Zygospores formation process

Zygomycota, a diverse group of fungi, employs a unique reproductive strategy centered around the formation of zygospores. Unlike many fungi that produce vast quantities of spores, Zygomycota typically generates a single, robust zygospore per reproductive event. This process, known as zygosporangium formation, is a fascinating interplay of cellular fusion and environmental adaptation.

The Mating Dance: A Tale of Two Gametangia

The journey begins with the encounter of two compatible hyphae, each belonging to a different mating type. At the tips of these hyphae, specialized structures called gametangia develop. These gametangia, often club-shaped or swollen, house the haploid gametes. When conditions are favorable, typically in response to nutrient scarcity or environmental stress, the gametangia come into close contact, initiating the mating process.

A delicate fusion of the gametangial walls follows, allowing the cytoplasm and nuclei of the two cells to mingle. This fusion, known as plasmogamy, marks the beginning of a new genetic entity.

Nuclear Union and Zygospore Maturation

Within the fused gametangia, the haploid nuclei from each parent remain distinct for a period, a stage called dikaryosis. This dikaryotic phase is crucial for genetic recombination. Eventually, the nuclei fuse, forming a diploid zygote nucleus. This zygote nucleus then undergoes meiosis, reducing the chromosome number back to haploid. The resulting haploid nuclei are packaged into a thick-walled, highly resistant structure called the zygospore.

The zygospore wall is a marvel of fungal engineering, composed of multiple layers that provide protection against desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other environmental insults. This durability allows zygospores to persist in the environment for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate.

Germination: Awakening from Dormancy

When environmental conditions become favorable, the zygospore germinates. The thick wall ruptures, and a germ tube emerges, giving rise to a new haploid mycelium. This mycelium will then grow, spread, and potentially repeat the reproductive cycle, ensuring the survival and propagation of the Zygomycota species.

The zygospore formation process is a testament to the adaptability and resilience of Zygomycota. By producing a single, highly resilient spore, these fungi ensure their genetic continuity even in challenging environments. Understanding this process not only sheds light on fungal biology but also has implications for fields like agriculture and biotechnology, where harnessing fungal resilience can be beneficial.

Clostridium Difficile Spores: Understanding Their Long-Term Viability and Persistence

You may want to see also

Aplanospores role in reproduction

Aplanospores, though less celebrated than other spore types, play a crucial role in the reproductive strategy of Zygomycota under specific environmental conditions. These non-motile spores are produced asexually, often in response to adverse conditions such as nutrient depletion or desiccation. Unlike zoospores, which are flagellated and require water for dispersal, aplanospores are resilient and can remain dormant until conditions improve. This adaptability ensures the survival of Zygomycota in unpredictable environments, making aplanospores a vital component of their life cycle.

To understand the practical application of aplanospores, consider their production process. When a Zygomycota organism senses environmental stress, it forms aplanospores within sporangia or directly from hyphae. These spores are typically thicker-walled and more resistant to harsh conditions than other spore types. For example, in laboratory settings, inducing aplanospore formation often involves gradually reducing nutrient availability or increasing salinity. Researchers can then observe how these spores remain viable for extended periods, sometimes years, until favorable conditions return.

From a comparative perspective, aplanospores differ significantly from other Zygomycota spores like zygospores and sporangiospores. While zygospores are sexual and result from the fusion of gametangia, and sporangiospores are asexual and produced in sporangia, aplanospores are a specialized response to stress. Their primary function is survival rather than immediate dispersal or reproduction. This distinction highlights the versatility of Zygomycota’s reproductive strategies, with aplanospores serving as a last resort in challenging environments.

For those studying or working with Zygomycota, understanding aplanospores offers practical benefits. For instance, in agriculture, recognizing aplanospore formation can indicate soil stress, prompting interventions like irrigation or nutrient supplementation. In biotechnology, aplanospores’ durability makes them candidates for preserving fungal strains long-term. To encourage aplanospore production, gradually expose cultures to stress conditions, monitor for spore formation, and store them in low-humidity environments. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of Zygomycota’s resilience but also provides actionable insights for applied fields.

Do Trees Have Spores? Unveiling the Secrets of Tree Reproduction

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental triggers for spore release

Zygomycota, a diverse group of fungi, relies on environmental cues to optimize spore release, ensuring successful dispersal and colonization. Among these triggers, humidity stands out as a critical factor. Sporangiospores, the primary reproductive units of Zygomycota, are often released when humidity levels reach a threshold, typically between 80% and 95%. This moisture facilitates the rupture of sporangia, allowing spores to escape and be carried by air currents. For example, in laboratory settings, researchers simulate this by maintaining high humidity chambers, observing peak spore release during these conditions. Practical applications include controlling indoor environments to prevent Zygomycota proliferation, such as using dehumidifiers in damp basements.

Temperature fluctuations also play a pivotal role in triggering spore release. Zygomycota species are particularly responsive to sudden temperature shifts, often releasing spores during cooler periods following warmth. This mechanism is thought to mimic natural transitions, such as evening temperature drops after a warm day. Field studies have shown that spore counts increase significantly during these thermal transitions, highlighting the fungi’s adaptability to environmental rhythms. Gardeners and farmers can leverage this knowledge by monitoring temperature changes to predict and manage Zygomycota outbreaks, especially in crop storage areas where temperature control is feasible.

Light exposure, particularly transitions between light and dark, acts as another environmental trigger. Many Zygomycota species exhibit phototropic responses, releasing spores during specific light cycles. For instance, some species release spores at dusk, a behavior believed to maximize dispersal during calmer evening air. This phenomenon is exploited in controlled environments like greenhouses, where light cycles are manipulated to suppress spore release and reduce fungal contamination. Home growers can replicate this by using timers on grow lights to disrupt the fungi’s reproductive cycle.

Physical disturbances, such as wind or rain, provide immediate cues for spore release. Zygomycota’s sporangia are often mechanically fragile, designed to burst upon contact with water droplets or air movement. In natural settings, rain-splashed spores can travel short distances, while wind carries them farther, aiding colonization. This mechanism underscores the importance of ventilation in indoor spaces to disperse spores and prevent accumulation. For instance, using fans in mold-prone areas can mimic natural wind, reducing spore concentration and mitigating fungal growth.

Chemical signals from neighboring organisms or decaying matter can also induce spore release. Zygomycota often thrives in nutrient-rich environments, and the presence of certain organic compounds triggers reproductive responses. For example, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by decaying plant material can stimulate sporangia to release spores, ensuring they land in fertile substrates. This insight is valuable in composting operations, where managing VOC levels can control Zygomycota populations. By understanding these chemical triggers, practitioners can design environments that either promote or inhibit fungal reproduction, depending on the desired outcome.

Unveiling the Underground Journey: How Truffles Disperse Their Spores

You may want to see also

Comparison of spore types in Zygomycota

Zygomycota, a diverse phylum of fungi, employs a variety of spore types for reproduction, each adapted to specific environmental conditions and life cycle stages. Understanding these spore types—zygospores, sporangiospores, and aplanospores—reveals the phylum's reproductive strategies and ecological roles. Zygospores, for instance, are thick-walled, highly resilient structures formed during sexual reproduction. They serve as survival units, capable of enduring harsh conditions such as desiccation and extreme temperatures. In contrast, sporangiospores are asexual spores produced within sporangia, thin-walled and designed for rapid dispersal. These spores are short-lived but efficient in colonizing favorable environments quickly. Aplanospores, though less common, are another asexual form, often produced under stress conditions, offering a middle ground between the durability of zygospores and the dispersal efficiency of sporangiospores.

Analyzing these spore types highlights their functional differences. Zygospores are the result of sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity and long-term survival. Their production is energy-intensive but crucial for species persistence in unpredictable environments. Sporangiospores, on the other hand, are the primary means of rapid propagation, allowing Zygomycota to exploit nutrient-rich niches swiftly. This dual reproductive strategy—sexual and asexual—maximizes the phylum's adaptability. For example, in a laboratory setting, researchers often induce zygospore formation by manipulating environmental factors like pH and nutrient availability, while sporangiospore production can be observed under optimal growth conditions.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between these spore types is essential for mycologists and ecologists. Zygospores are typically identified by their size (20–100 μm) and dark, thick walls, often requiring microscopy for detailed examination. Sporangiospores, being smaller (5–10 μm) and lighter, are more easily dispersed and detected in air samples. Aplanospores, though rare, can be differentiated by their intermediate characteristics and context of formation. For instance, in agricultural settings, monitoring sporangiospore counts can predict fungal outbreaks, while zygospore detection indicates long-term fungal presence in soil.

Persuasively, the study of Zygomycota spore types underscores the importance of fungal diversity in ecosystems. Each spore type plays a unique role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships. For example, zygospores contribute to soil health by persisting through adverse conditions, ensuring fungal populations rebound when resources become available. Sporangiospores, by rapidly colonizing organic matter, accelerate decomposition processes. This knowledge can inform conservation efforts and agricultural practices, such as using spore counts to optimize fungicide application timing or enhancing soil biodiversity through managed fungal populations.

In conclusion, the comparison of spore types in Zygomycota reveals a sophisticated reproductive system tailored to environmental challenges. Zygospores, sporangiospores, and aplanospores each fulfill distinct ecological functions, from long-term survival to rapid colonization. By understanding these differences, researchers and practitioners can better manage fungal populations in various contexts, from laboratories to agricultural fields. This knowledge not only advances mycological science but also highlights the critical role of fungi in sustaining ecosystems.

Discovering New Space Colonies: Tips to Find Your Next Spore Adventure

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Zygomycota produces a variable number of spores, but typically, a single sporangium can contain hundreds to thousands of spores.

Zygomycota primarily reproduces using asexual spores called sporangiospores, which are produced inside a sporangium.

Yes, Zygomycota can also reproduce sexually by forming zygospores, which are thick-walled spores resulting from the fusion of gametangia.

Spores in Zygomycota are dispersed through various means, including wind, water, or insects, after the sporangium ruptures or dries out.

The spores of Zygomycota, such as sporangiospores and zygospores, are typically unicellular structures.