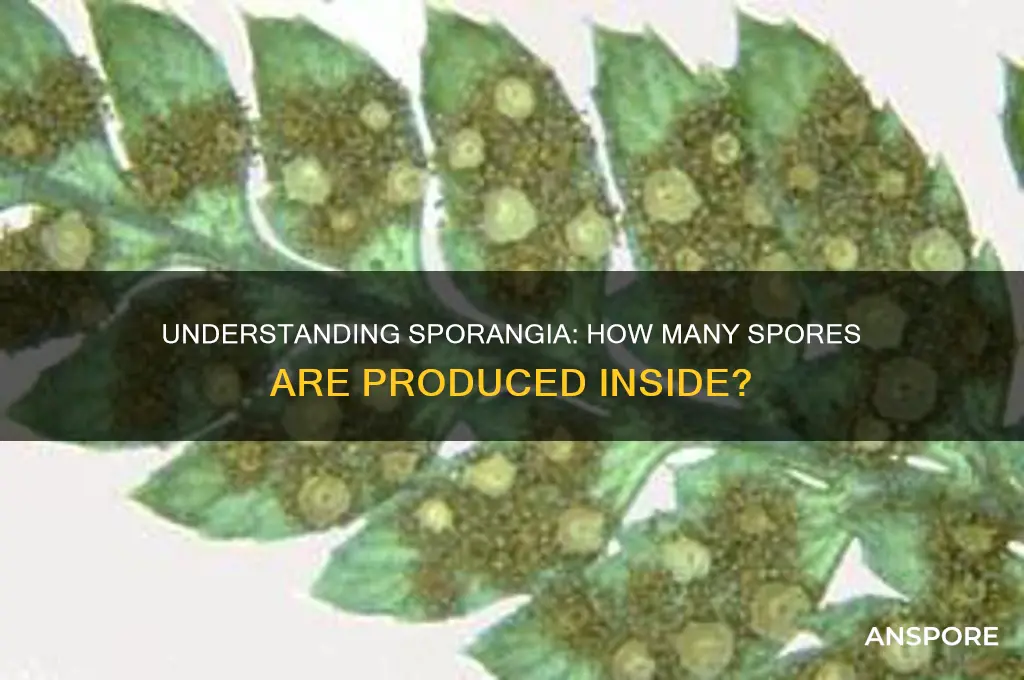

The sporangia, a vital structure in the life cycle of many plants and fungi, serves as a protective sac that houses and disperses spores. Understanding the number of spores within a sporangium is crucial for studying reproductive strategies, ecological roles, and evolutionary adaptations of spore-producing organisms. Typically, the quantity of spores in a sporangium varies widely depending on the species, environmental conditions, and developmental stage. For instance, a single sporangium in ferns may contain hundreds to thousands of spores, while in certain fungi, the count can range from a few dozen to several thousand. This variability highlights the complexity and diversity of spore production mechanisms across different organisms, making it an intriguing area of research in botany and mycology.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangium Structure and Function: Understanding the role and anatomy of sporangia in spore production

- Spore Count Variability: Factors influencing the number of spores within a single sporangium

- Species-Specific Spore Counts: How spore numbers differ across various plant and fungal species

- Environmental Impact on Spores: Effects of conditions like humidity and temperature on spore production

- Methods for Counting Spores: Techniques used to accurately measure spores within sporangia

Sporangium Structure and Function: Understanding the role and anatomy of sporangia in spore production

The sporangium, a critical structure in the life cycle of many plants and fungi, serves as the factory for spore production. Its anatomy is finely tuned to protect and disperse spores, ensuring the survival and propagation of the species. Typically, a single sporangium can contain anywhere from a few dozen to several thousand spores, depending on the organism. For instance, a fern sporangium may house 64 spores, while certain fungal species can produce up to 10,000 spores per sporangium. This variability highlights the adaptability of sporangia across different organisms.

To understand the sporangium’s function, consider its structure. In ferns, sporangia are clustered into sori on the underside of leaves. Each sporangium is a sac-like structure with a wall that responds to environmental cues, such as humidity, to trigger spore release. In fungi, sporangia are often more robust, with thick walls that protect spores until optimal dispersal conditions arise. The number of spores within a sporangium is directly tied to its size and the organism’s reproductive strategy. For example, species in nutrient-rich environments may produce fewer, larger spores, while those in harsh conditions often produce many smaller spores to increase dispersal success.

Practical observation of sporangia can be a rewarding exercise for enthusiasts and educators. To examine a sporangium, collect a mature fern frond and use a magnifying glass to locate the sori. Gently tapping the frond over a piece of paper will release the spores, allowing you to count them under a microscope. For fungal sporangia, such as those of *Pilobolus*, observe their explosive discharge mechanism, which can propel spores up to 2 meters. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the sporangium’s role but also underscores its efficiency in spore dispersal.

Comparatively, the sporangium’s design is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. Unlike seeds, which contain embryonic plants and nutrient stores, spores are minimalist survival units, relying on the sporangium for protection and dispersal. This distinction reflects the sporangium’s dual role as both a shelter and a launchpad. Its structure—often featuring elastic walls or specialized openings—ensures that spores are released only when conditions favor germination. For instance, some fungal sporangia have a drop of fluid that propels spores when disturbed, a mechanism akin to a biological spring.

In conclusion, the sporangium’s structure and function are intricately linked to its role in spore production. Whether housing dozens or thousands of spores, its design maximizes reproductive success through protection and efficient dispersal. By studying sporangia, we gain insights into the diversity of life’s strategies for survival and propagation. For those interested in botany or mycology, understanding the sporangium offers a window into the fascinating world of plant and fungal reproduction.

Dry Rot Spores: Uncovering Potential Health Risks and Concerns

You may want to see also

Spore Count Variability: Factors influencing the number of spores within a single sporangium

The number of spores within a sporangium can vary dramatically, even among the same species. For instance, *Physarum polycephalum*, a slime mold, produces sporangia containing anywhere from 50 to 500 spores, depending on environmental conditions. This variability is not random but influenced by a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and developmental factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and biotechnology, where spore count directly impacts propagation, disease spread, and experimental consistency.

Environmental stressors play a pivotal role in shaping spore count. Nutrient availability, for example, is a critical determinant. In *Neurospora crassa*, a model fungus, sporangia grown on media rich in nitrogen and carbon produce 2-3 times more spores than those on minimal media. Similarly, temperature fluctuations can induce stress responses, leading to reduced spore production. A study on *Aspergillus nidulans* showed that temperatures above 37°C halved the average spore count per sporangium compared to optimal growth at 30°C. Humidity and light exposure also influence spore development, with arid conditions or prolonged darkness often resulting in smaller, less populated sporangia.

Genetic factors provide the blueprint for spore production but allow for flexibility. Mutations in genes controlling meiosis or sporulation can drastically alter spore count. For example, knockout mutations in the *spo11* gene, essential for DNA recombination during meiosis, can reduce spore production in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* by up to 80%. Conversely, overexpression of genes like *brlA* in *Aspergillus* species, which regulates conidiation, can increase spore yield by 40-50%. Genetic diversity within a population also contributes to variability, as different strains may have evolved distinct sporulation strategies in response to their specific ecological niches.

Developmental timing and spatial organization within the sporangium further modulate spore count. In many fungi, spore formation is a highly coordinated process. Premature or delayed initiation of sporulation can lead to incomplete or overcrowded sporangia. For instance, in *Magnaporthe oryzae*, the rice blast fungus, disruption of the *COM1* pheromone signaling pathway results in asynchronous spore development, reducing the average count by 30%. Additionally, the physical arrangement of spores within the sporangium can influence their viability and number. In *Zygomycota*, spores at the periphery of the sporangium often mature faster and are more numerous than those in the center, where nutrient diffusion is limited.

Practical implications of spore count variability demand precise control in applied settings. In agriculture, inconsistent spore counts in biocontrol agents like *Trichoderma* can compromise their efficacy against pathogens. To mitigate this, growers often use standardized growth media and controlled environments to optimize spore production. In biotechnology, where spores are used for enzyme production or genetic studies, researchers employ techniques like flow cytometry to quantify spores accurately. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, maintaining stable humidity (85-90%) and temperature (22-25°C) during the pinning stage can significantly enhance spore yield per sporangium.

By dissecting the factors influencing spore count variability, we gain insights into the resilience and adaptability of spore-producing organisms. Whether in the lab, field, or kitchen, understanding these dynamics empowers us to harness the potential of spores more effectively, from combating crop diseases to advancing scientific discovery.

Are Pine Cones Spores? Unraveling Nature's Seed Dispersal Mysteries

You may want to see also

Species-Specific Spore Counts: How spore numbers differ across various plant and fungal species

The number of spores produced within a sporangium varies dramatically across species, reflecting unique evolutionary strategies and ecological roles. For instance, a single sporangium of the fern *Pteridium aquilinum* can contain upwards of 64 spores, optimized for rapid colonization of disturbed habitats. In contrast, the sporangia of certain mosses, like *Physcomitrella patens*, typically house fewer than 10 spores, a trait linked to their reliance on water for sperm dispersal. This disparity highlights how spore count is finely tuned to the reproductive needs and environmental pressures of each species.

Analyzing fungal species reveals even more striking differences. The model fungus *Neurospora crassa* produces approximately 50–100 spores per sporangium, a moderate count that balances dispersal efficiency with resource conservation. Conversely, the pathogenic fungus *Aspergillus fumigatus* can generate over 3,000 spores per sporangium (technically, a conidiophore), a prolific output that enhances its ability to spread and infect hosts. Such variations underscore the role of spore count in fungal survival strategies, from benign decomposition to virulent pathogenesis.

Practical applications of species-specific spore counts are evident in agriculture and conservation. For example, understanding that a single sporangium of the water mold *Phytophthora infestans* (cause of late blight in potatoes) releases 50–100 spores helps farmers implement targeted fungicide applications during peak spore release. Similarly, conservationists monitoring rare fern species can use spore counts as a proxy for reproductive health, with low counts signaling potential population decline. These insights demonstrate the utility of spore count data in real-world scenarios.

Comparing spore counts across kingdoms further illuminates evolutionary trade-offs. While plant sporangia often prioritize quality over quantity, producing fewer but larger, nutrient-rich spores, fungal sporangia tend to favor quantity, releasing vast numbers of smaller, lightweight spores for wind dispersal. This divergence reflects the distinct challenges faced by plants and fungi: the former must anchor themselves in place, while the latter thrive on mobility. By studying these differences, researchers can unravel the intricate relationship between spore count and ecological success.

To harness this knowledge effectively, consider these practical tips: when cultivating spore-bearing species, monitor sporangium maturity to optimize spore collection—for ferns, harvest when sporangia turn brown; for fungi, collect during active sporulation. For research or conservation, standardize spore counts by normalizing to sporangium size or environmental conditions, as humidity and temperature can influence production. Finally, leverage species-specific data to tailor interventions, whether combating fungal pathogens or restoring endangered plant populations. Understanding spore counts is not just an academic exercise—it’s a tool for action.

Understanding Mould Spores: How They Spread and Thrive in Your Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Impact on Spores: Effects of conditions like humidity and temperature on spore production

The number of spores within a sporangium can vary dramatically, from a few dozen to several thousand, depending on the species and environmental conditions. This variability is not random; it’s a direct response to the surrounding environment, particularly humidity and temperature. For instance, *Physarum polycephalum*, a slime mold, produces fewer but larger spores under high humidity, while *Aspergillus niger*, a common fungus, increases spore count in warm, dry conditions. Understanding these responses is crucial for fields like agriculture, where spore production directly impacts crop health and disease spread.

Humidity acts as a double-edged sword for spore production. Optimal moisture levels (typically 70–90% relative humidity) encourage spore formation by facilitating the growth of hyphal networks and the maturation of sporangia. However, excessive humidity can lead to spore clumping, reducing dispersal efficiency. Conversely, low humidity (<50%) triggers stress responses in many fungi, prompting them to produce smaller, more resilient spores. For example, *Botrytis cinerea*, a grapevine pathogen, increases spore output under moderate humidity but halts production below 40%. Practical tip: Maintain greenhouse humidity at 75% to balance spore production and prevent fungal diseases without hindering dispersal.

Temperature plays an equally pivotal role, often dictating the timing and quantity of spore release. Most fungi thrive in mesophilic conditions (20–30°C), where spore production peaks. *Fusarium graminearum*, a wheat pathogen, maximizes spore output at 25°C but drastically reduces it above 35°C. Cold temperatures (<10°C) can delay spore maturation, while heat stress (>35°C) may trigger early release of underdeveloped spores. Comparative analysis shows that thermophilic fungi like *Thermomyces lanuginosus* produce spores optimally at 45°C, highlighting species-specific adaptations. Caution: Sudden temperature shifts can disrupt spore viability, so gradual acclimation is key in controlled environments.

The interplay of humidity and temperature creates a dynamic landscape for spore production. For instance, *Penicillium expansum*, a post-harvest apple pathogen, requires 25°C and 85% humidity to produce its maximum spore count. Deviations from these conditions reduce spore numbers by up to 70%. In contrast, *Alternaria alternata*, a ubiquitous allergen, thrives in warmer (30°C) and drier (60% humidity) conditions, producing spores in abundance. Takeaway: Tailoring environmental conditions to specific fungal species can either suppress or enhance spore production, offering a strategic tool for disease management.

To harness this knowledge, consider these actionable steps: Monitor humidity and temperature daily in high-risk areas like crop fields or storage facilities. Use dehumidifiers or misting systems to maintain optimal levels, and avoid abrupt temperature changes during critical growth phases. For example, reducing humidity to 60% during the late stages of *Aspergillus* growth can minimize spore clumping without sacrificing production. By manipulating these environmental factors, you can predict and control spore output, mitigating risks while optimizing natural processes.

Can Black Mold Spores Be Deadly? Uncovering the Lethal Truth

You may want to see also

Methods for Counting Spores: Techniques used to accurately measure spores within sporangia

The number of spores within a sporangia varies widely across species, with some fungi producing as few as 4 spores per sporangium, while others, like certain ferns, can contain up to 64 or more. Accurately counting these spores is crucial for research in botany, mycology, and agriculture, yet the task is complicated by their microscopic size and the sporangia’s often opaque structure. Methods for counting spores must balance precision with practicality, as the technique chosen can significantly impact the reliability of results. Below, we explore several techniques tailored to different experimental needs and constraints.

Direct Microscopy with Hemacytometer: A Hands-On Approach

For small-scale studies or species with accessible sporangia, direct microscopy using a hemacytometer is a straightforward method. First, carefully rupture the sporangium using a sterile needle or scalpel under a dissecting microscope. Suspend the released spores in a known volume of sterile water or buffer solution, ensuring thorough mixing to avoid clumping. Place a 10 μL drop of the suspension onto a hemacytometer grid, count the spores in multiple squares, and calculate the concentration per unit volume. This method is ideal for species like *Physarum polycephalum*, where sporangia are large and easy to manipulate. However, it requires skill in handling delicate structures and may underestimate counts if spores adhere to the sporangium walls.

Fluorescent Staining and Flow Cytometry: Precision at Scale

When working with smaller sporangia or requiring high-throughput analysis, fluorescent staining combined with flow cytometry offers unparalleled accuracy. Treat the spore suspension with a DNA-binding dye like SYBR Green (1:10,000 dilution) for 15–30 minutes in the dark to label nuclei. Pass the stained sample through a flow cytometer, which detects fluorescence and counts individual spores based on their size and nucleic acid content. This technique is particularly useful for species like *Phytophthora infestans*, where sporangia are tiny and numerous. While flow cytometry requires specialized equipment, it minimizes human error and can process thousands of samples daily, making it suitable for large-scale studies or pathogen monitoring.

Image Analysis Software: Automating the Count

Advances in digital microscopy and image analysis have introduced automated methods for spore counting. Capture high-resolution images of the sporangium cross-section or spore suspension using a compound microscope with a digital camera. Software like ImageJ or specialized algorithms can then analyze the images, distinguishing spores from debris based on size, shape, and intensity thresholds. For instance, applying a particle analysis tool with a size filter of 5–15 μm (typical spore diameter) can yield accurate counts for species like *Pilobolus*, whose sporangia are translucent. This method reduces bias but requires careful calibration and high-quality imaging to avoid over- or undercounting.

Comparative Analysis: Choosing the Right Technique

Each counting method has trade-offs. Direct microscopy is cost-effective and accessible but labor-intensive and prone to variability. Flow cytometry provides precision and speed but demands expensive equipment and staining expertise. Image analysis bridges the gap, offering automation with moderate resource requirements, though it relies on clear imaging conditions. For field studies or resource-limited settings, direct microscopy remains the go-to, while labs with advanced infrastructure may prefer flow cytometry or image analysis. Tailoring the technique to the species and experimental goals ensures both accuracy and efficiency in determining spore counts within sporangia.

Does Bleach Kill Ringworm Spores? Effective Disinfection Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The number of spores in a sporangium varies by species, but it can range from a few dozen to several thousand, depending on the organism and environmental conditions.

No, the number of spores produced in a sporangium differs among species and can be influenced by factors like nutrient availability, humidity, and genetic traits.

While rare, some species produce sporangia with only one spore, but most commonly, sporangia contain multiple spores to ensure successful dispersal and reproduction.

Generally, larger sporangia can house more spores, but the exact relationship depends on the species and the efficiency of spore-producing structures within the sporangium.