The concept of how many spores in CFU is a critical aspect of microbiology, particularly in the study of bacterial and fungal populations. CFU, or Colony Forming Units, is a measure used to quantify the number of viable cells or spores capable of forming visible colonies on a culture medium. When discussing spores, which are highly resistant dormant forms of microorganisms, understanding their concentration in terms of CFU is essential for various applications, including food safety, pharmaceutical production, and environmental monitoring. The relationship between spore count and CFU is influenced by factors such as spore viability, germination efficiency, and the specific conditions of the culture medium, making it a nuanced yet vital parameter in microbial analysis.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Understanding CFU (Colony Forming Units)

Colony Forming Units (CFUs) are a critical measure in microbiology, quantifying the number of viable cells or spores capable of forming colonies under specific conditions. When discussing how many spores in CFU, it’s essential to understand that CFU counts represent the number of active, cultivable spores in a sample, not the total spore count. This distinction is crucial because not all spores are viable or will germinate under given conditions. For instance, in probiotic supplements, a typical dosage ranges from 1 billion to 100 billion CFUs, indicating the number of live microorganisms present. However, this doesn’t account for dormant or non-viable spores, which may be present in higher numbers but do not contribute to CFU counts.

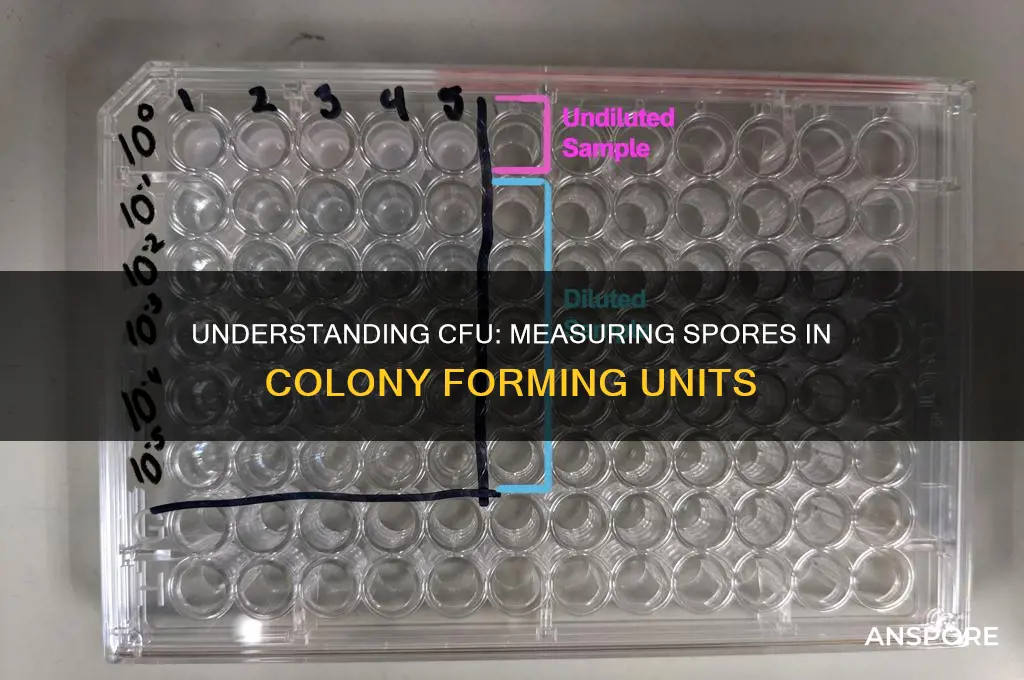

To determine how many spores in CFU, scientists use dilution plating or spread plating techniques, where a sample is diluted and plated on growth media. Colonies that form after incubation are counted, and the CFU value is extrapolated based on the dilution factor. For example, if 0.1 mL of a 10^-6 dilution yields 30 colonies, the CFU count is calculated as 30 / (0.1 * 10^-6) = 3 * 10^8 CFU/mL. This method assumes each colony arises from a single viable spore or cell, though clumping or chaining can lead to underestimation. In spore-specific studies, such as those involving *Bacillus* species, heat or chemical treatment may be applied to activate spores before plating, ensuring a more accurate CFU count.

A key challenge in correlating how many spores in CFU is the variability in spore viability and germination rates. Spores can remain dormant for years, and their ability to form colonies depends on environmental factors like temperature, pH, and nutrient availability. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores may have a germination rate of 90% under optimal conditions, but this drops significantly in suboptimal environments. This variability means CFU counts may underestimate the total spore population, particularly in samples with high spore concentrations but low germination rates. Researchers often use multiple plating techniques or alternative methods like flow cytometry to improve accuracy.

Practical applications of understanding how many spores in CFU are widespread. In the food industry, CFU counts are used to assess microbial contamination, with regulatory limits often set at <100 CFU/g for pathogens like *Salmonella*. In biotechnology, CFU measurements ensure consistent spore concentrations in products like biofertilizers or biopesticides. For consumers, knowing the CFU count in probiotics helps gauge potency, though higher CFUs don’t always equate to better efficacy. For example, a 10 billion CFU probiotic may be more effective than a 100 billion CFU product if the strains are better suited to the gut environment. Always follow dosage guidelines, typically 1–10 billion CFUs daily for adults, and consult a healthcare provider for specific needs.

In summary, while CFU counts provide a standardized measure of viable spores, they do not reflect the total spore population. Understanding how many spores in CFU requires consideration of spore viability, germination conditions, and methodological limitations. Whether in research, industry, or personal health, accurate CFU interpretation ensures informed decision-making and effective applications. For precise spore quantification, complement CFU data with additional techniques like microscopy or molecular methods to capture the full picture.

Microban's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation in Microorganisms

Spore formation is a survival mechanism employed by certain microorganisms, notably bacteria and fungi, to endure harsh environmental conditions. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals, allowing them to persist in environments that would otherwise be lethal. This resilience is achieved through a combination of structural modifications, such as a thick spore coat and reduced water content, and metabolic dormancy. Understanding spore formation is crucial when quantifying microbial populations, as spore-forming organisms can significantly impact colony-forming unit (CFU) counts in laboratory and industrial settings.

In the context of CFU measurements, spore-forming microorganisms present a unique challenge. A single CFU represents one viable cell capable of forming a colony under specific growth conditions. However, spores do not immediately form colonies upon plating; they must first germinate and revert to their vegetative state. This germination process can be influenced by factors such as temperature, nutrient availability, and pH, leading to variability in CFU counts. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores require specific triggers, such as L-valine and high temperatures, to initiate germination. Failure to account for these requirements can result in underestimating the true number of spores in a sample.

To accurately quantify spores in CFU, specialized techniques are often employed. One common method is the heat-shock treatment, where samples are exposed to high temperatures (e.g., 80°C for 10 minutes) to kill vegetative cells while leaving spores intact. This ensures that only spores contribute to the CFU count. Another approach is the use of selective media that inhibit vegetative cell growth while allowing spores to germinate and form colonies. For example, DSMZ Medium 101 is specifically designed to enumerate *Bacillus* spores by suppressing the growth of non-spore-forming bacteria. These methods highlight the importance of tailoring experimental conditions to the unique biology of spore-forming organisms.

Comparatively, non-spore-forming microorganisms lack the ability to produce spores, making their CFU counts more straightforward. However, spore-forming organisms require a deeper understanding of their life cycle and environmental triggers. For instance, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* species, may require specific humidity levels and nutrients to germinate. In industrial applications, such as food preservation and pharmaceutical manufacturing, misestimating spore counts can lead to contamination or product failure. Thus, precise quantification of spores in CFU is not just a laboratory exercise but a critical aspect of ensuring safety and efficacy in various industries.

In practical terms, researchers and professionals must consider several factors when working with spore-forming microorganisms. First, validate the germination conditions to ensure all spores have the opportunity to form colonies. Second, use appropriate controls, such as untreated samples, to distinguish between vegetative cells and spores. Finally, document the methodology clearly, as small variations in protocol can significantly affect results. By mastering these techniques, one can accurately determine the number of spores in CFU, providing valuable insights into microbial populations and their potential impact on health, industry, and the environment.

Are Mildew Spores Dangerous? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Methods to Count Spores in CFU

Counting spores in Colony Forming Units (CFU) is a critical process in microbiology, particularly for assessing microbial contamination or viability in samples. One of the most widely used methods is the spread plate technique, where a known volume of a diluted spore suspension is evenly distributed across the surface of an agar plate. After incubation, the number of visible colonies is counted, and the CFU per unit volume is calculated based on the dilution factor. This method is straightforward but requires careful technique to avoid overloading the plate, which can lead to overlapping colonies and inaccurate counts.

For samples with extremely high spore concentrations, the pour plate method offers a more controlled approach. Here, the diluted spore suspension is mixed with molten agar and poured into a Petri dish. As the agar solidifies, the spores become evenly distributed throughout the medium. Colonies grow both on the surface and within the agar, allowing for higher spore loads to be counted accurately. However, this method is more time-consuming and requires precise temperature control to avoid killing the spores during the pouring process.

When dealing with low spore concentrations, membrane filtration becomes a preferred technique. The sample is filtered through a sterile membrane, which is then placed on an agar plate. Spores trapped on the membrane grow into colonies, which can be counted directly. This method is particularly useful for water or air samples, where spores are often present in low numbers. The filtration step ensures that even a small number of spores are retained and detectable, enhancing sensitivity.

Advanced technologies like flow cytometry and quantitative PCR (qPCR) provide alternative approaches to traditional plating methods. Flow cytometry uses fluorescent dyes to detect and count individual spores based on their size and nucleic acid content, offering rapid results with high precision. qPCR, on the other hand, quantifies spore-specific DNA sequences, allowing for species-level identification. While these methods are more expensive and require specialized equipment, they offer unparalleled accuracy and speed, especially in research or industrial settings where traditional methods fall short.

Regardless of the method chosen, proper dilution and replication are essential for reliable results. Diluting the sample ensures that colonies do not overlap, while replicating plates reduces counting errors and increases confidence in the data. For example, a 1:100 dilution of a spore suspension plated in triplicate can provide a robust estimate of CFU, with variations between plates indicating the need for further dilution or replication. Practical tips include using sterile techniques to avoid contamination and incubating plates at optimal temperatures (e.g., 37°C for most bacteria) for 24–48 hours to ensure colony growth.

Bacillus Anthracis Spores: Understanding Their Role in Anthrax Infections

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Factors Affecting Spore Viability

Spore viability is a critical factor in determining the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) in a given sample. Understanding the elements that influence spore survival is essential for accurate quantification and practical applications in fields like microbiology and biotechnology. One of the primary factors affecting spore viability is temperature exposure. Spores can withstand extreme temperatures, but prolonged exposure to high heat or repeated freeze-thaw cycles can significantly reduce their ability to germinate. For instance, spores of *Bacillus subtilis* exposed to 100°C for 10 minutes retain 90% viability, but this drops to 50% after 20 minutes. Conversely, freezing spores without cryoprotectants like glycerol (typically 10-15% v/v) can lead to ice crystal formation, damaging cell structures and reducing CFU counts by up to 70%.

Another critical factor is humidity and storage conditions. Spores are remarkably resilient in dry environments, but even slight moisture can trigger premature germination or degradation. For example, storing spores at 20% relative humidity (RH) can maintain viability for years, whereas 80% RH reduces viability by 50% within six months. Practical storage tips include using desiccants like silica gel and airtight containers to minimize moisture exposure. Additionally, light exposure, particularly UV radiation, can damage spore DNA, reducing CFU counts. Wrapping storage containers in aluminum foil or using amber vials can mitigate this effect, preserving viability for extended periods.

Chemical exposure also plays a significant role in spore viability. Disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide (3-6% concentration) and ethanol (70%) are effective at inactivating spores, but their efficacy depends on contact time and spore species. For instance, *Clostridium difficile* spores require 10 minutes of exposure to 6% hydrogen peroxide for complete inactivation, while *Bacillus anthracis* spores are more resistant, needing up to 30 minutes. In industrial settings, residual chemicals from cleaning processes can inadvertently reduce spore viability in samples, leading to underestimations of CFU counts. To counteract this, rinsing samples with sterile water or buffer solutions before enumeration is recommended.

Finally, nutrient availability and pH influence spore germination and viability. Spores require specific triggers, such as L-alanine or inosine, to initiate germination. In the absence of these nutrients, spores remain dormant, and CFU counts may appear lower than expected. pH levels outside the optimal range (typically 7.0-7.5) can also inhibit germination. For example, acidic conditions (pH < 5) can denature spore proteins, while alkaline environments (pH > 9) disrupt cell membranes. When preparing spore suspensions for CFU enumeration, using nutrient-rich media like nutrient agar and maintaining neutral pH ensures accurate viability assessments.

In summary, spore viability is influenced by a combination of environmental and chemical factors, each requiring careful consideration in experimental design and storage practices. By controlling temperature, humidity, chemical exposure, and nutrient conditions, researchers can maximize spore survival and obtain reliable CFU counts. Practical steps, such as using cryoprotectants, desiccants, and protective packaging, can significantly enhance spore longevity and accuracy in quantification.

Understanding Botulism Spores: Germination Timeline and Factors Explained

You may want to see also

Applications of Spore CFU Measurement

Spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, produce highly resistant endospores that can survive extreme conditions. Measuring the number of spores in colony-forming units (CFU) is critical for assessing microbial contamination, sterilization efficacy, and product safety. This technique quantifies viable spores capable of growing into colonies under specific conditions, providing actionable data for industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to food production.

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, spore CFU measurement ensures the effectiveness of sterilization processes like autoclaving or gamma irradiation. For instance, a common validation involves exposing spore strips containing *Geobacillus stearothermophilus* (10^6 spores/strip) to steam sterilization at 121°C for 15–20 minutes. Post-sterilization, the strips are incubated at 55–60°C for 24–48 hours. Absence of growth confirms successful sterilization, while any CFU detected indicates process failure. This method is mandated by regulatory bodies like the FDA and USP to ensure product sterility.

Food and beverage industries rely on spore CFU measurement to detect heat-resistant contaminants, particularly in canned goods and dairy products. *Bacillus cereus* and *Clostridium botulinum* spores are common targets. For example, in canned vegetables, a sample is heated to 80°C for 10 minutes to activate spores, then plated on nutrient agar and incubated at 30°C for 48 hours. A CFU count exceeding 10^2/g indicates potential spoilage or safety risks. This process helps manufacturers comply with food safety standards and extend product shelf life.

Environmental monitoring in cleanrooms and laboratories uses spore CFU measurement to assess air and surface contamination. Settle plates containing tryptic soy agar are exposed to the environment for 1–4 hours, then incubated at 37°C for 24–48 hours. A CFU count above 1/plate in ISO Class 5 cleanrooms signals contamination. This method is essential for maintaining sterile conditions in biotechnology, semiconductor manufacturing, and surgical suites, where even a single spore can compromise operations.

Finally, spore CFU measurement plays a role in developing antimicrobial agents and disinfectants. Researchers expose spore suspensions (e.g., 10^6 *Bacillus subtilis* spores/mL) to varying concentrations of disinfectants for defined contact times. Post-exposure, samples are neutralized, diluted, and plated on nutrient agar. A 99.9999% (6-log) reduction in CFU compared to the control demonstrates efficacy, meeting EPA or EN standards. This data guides product formulation and application protocols for healthcare, agriculture, and household use.

By providing precise, quantifiable data, spore CFU measurement underpins critical decisions across industries, ensuring safety, compliance, and innovation. Its applications highlight the versatility of this technique in addressing microbial challenges in diverse contexts.

Can Ceila Effectively Block Spores? Exploring Its Protective Capabilities

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

CFU stands for Colony Forming Units, which is a measure used to estimate the number of viable spores or cells in a sample based on their ability to form colonies under specific growth conditions.

The number of spores in CFU is determined by diluting a sample, plating it on a growth medium, incubating it, and counting the number of colonies that form. Each colony typically represents one viable spore or cell.

Yes, the number of spores in CFU can vary significantly between different types of microorganisms due to differences in spore formation, viability, and growth requirements.

Measuring spores in CFU is important in microbiology for assessing microbial contamination, evaluating sterilization processes, studying spore viability, and ensuring product safety in industries like food, pharmaceuticals, and healthcare.