Eating wild mushrooms can be extremely risky due to the difficulty in distinguishing between edible and toxic species, even for experienced foragers. Many poisonous mushrooms closely resemble their safe counterparts, and consuming the wrong one can lead to severe symptoms, including organ failure, neurological damage, or even death. Common toxic varieties like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) are particularly dangerous, often causing delayed symptoms that make timely treatment challenging. Additionally, cooking or drying does not always neutralize toxins, and there is no universal rule to identify safe mushrooms by appearance alone. Without proper knowledge, tools, or expert guidance, foraging for wild mushrooms poses a significant health hazard, making it a practice best avoided by amateurs.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Toxic Species Identification: Learn to recognize poisonous mushrooms to avoid deadly mistakes in foraging

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Understand early signs of mushroom toxicity for prompt medical intervention

- Safe Foraging Practices: Follow expert guidelines to minimize risks while collecting wild mushrooms

- Regional Mushroom Risks: Know local toxic species and their habitats to avoid accidental ingestion

- Cooking and Preparation: Properly prepare wild mushrooms to reduce potential toxins and ensure safety

Toxic Species Identification: Learn to recognize poisonous mushrooms to avoid deadly mistakes in foraging

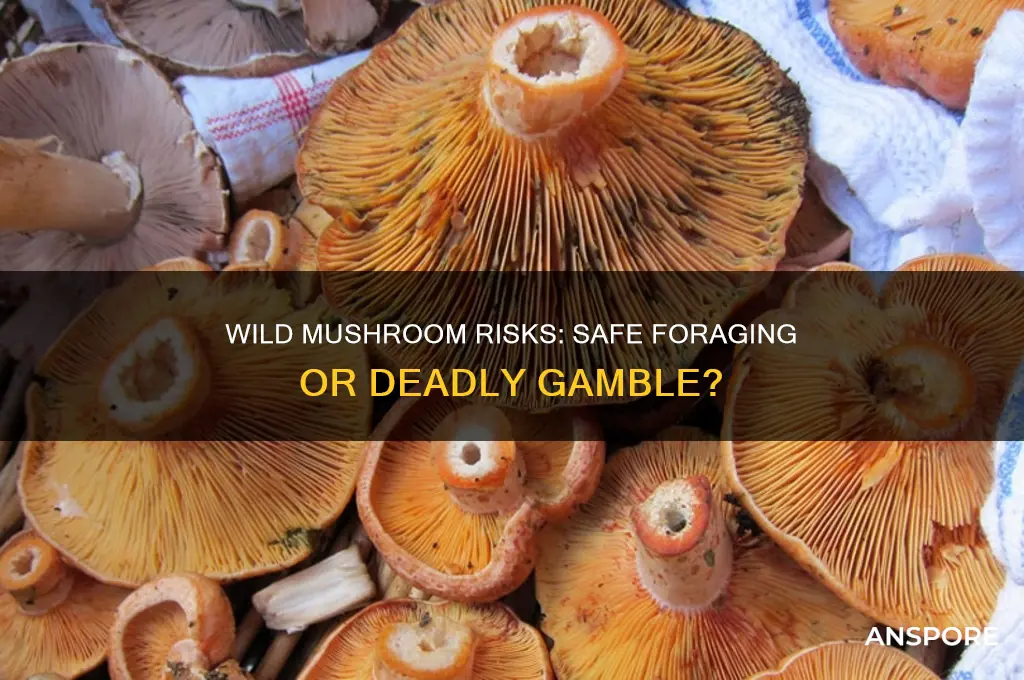

Eating wild mushrooms can be a rewarding culinary adventure, but it comes with significant risks, especially when it comes to toxic species. Toxic Species Identification is a critical skill for anyone interested in foraging, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. The first step in safe foraging is understanding that many poisonous mushrooms closely resemble edible varieties, making it essential to learn the specific characteristics of toxic species. For instance, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) is often mistaken for edible mushrooms like the Paddy Straw (*Coprinus comatus*) due to its similar size and color. However, the Death Cap contains potent toxins that can cause liver and kidney failure.

To avoid deadly mistakes, foragers must familiarize themselves with key identifiers of toxic mushrooms. These include gill color, spore print, cap shape, and the presence of a volva or ring. For example, the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) has a pure white appearance, free gills, and a distinctive volva at the base, all of which are red flags. Another dangerous species, the Galerina (*Galerina marginata*), often grows on wood and has rusty brown spores, which can be identified by taking a spore print. Learning these features requires hands-on practice and reliable field guides, as well as cross-referencing with expert resources.

One of the most treacherous aspects of toxic mushrooms is their delayed symptoms. Many poisonous species, like the Conocybe filaris, cause symptoms only hours or even days after ingestion, leading foragers to falsely believe the mushroom is safe. This delay can result in irreversible damage before medical help is sought. Therefore, never consume a wild mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity, and even then, start with a small amount to test for allergic reactions.

Additionally, relying on folklore or myths, such as "poisonous mushrooms taste bad" or "animals avoid toxic mushrooms," can be fatal. These misconceptions have no scientific basis and have led to numerous poisonings. Instead, focus on systematic identification methods, such as examining the mushroom’s habitat, season, and physical traits. Joining local mycological societies or attending foraging workshops can provide valuable hands-on experience and mentorship from experts.

Lastly, always carry a reliable field guide and consider using digital tools like mushroom identification apps, though these should never replace human expertise. If in doubt, discard the mushroom entirely. The risks of toxic species are too high to take chances. By mastering toxic species identification, foragers can enjoy the bounty of the wild while minimizing the dangers associated with this ancient practice. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms, but to avoid the deadly ones.

Cow Manure Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Toxic Treat?

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning: Understand early signs of mushroom toxicity for prompt medical intervention

Eating wild mushrooms can be extremely risky due to the difficulty in distinguishing between edible and toxic species. Even experienced foragers can make mistakes, and the consequences of consuming a poisonous mushroom can be severe or even fatal. Understanding the early signs of mushroom toxicity is crucial for prompt medical intervention, as timely treatment can significantly improve outcomes. Symptoms of mushroom poisoning can vary widely depending on the type of toxin involved, but there are common indicators that should never be ignored.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms are often the first signs of mushroom poisoning and typically appear within 6 to 24 hours after ingestion. These may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and cramps. While these symptoms can mimic common food poisoning, their onset after consuming wild mushrooms should raise immediate concern. For example, mushrooms containing amatoxins, such as the deadly Amanita species, often cause severe gastrointestinal distress followed by a temporary improvement before more serious symptoms develop. Recognizing this pattern is vital for seeking urgent medical care.

Neurological Symptoms can also occur, particularly with mushrooms containing toxins like muscarine, psilocybin, or ibotenic acid. These may manifest as confusion, dizziness, hallucinations, muscle spasms, or seizures. Some toxic mushrooms, like the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), can cause altered mental states or delirium. Others, such as certain Clitocybe species, may lead to excessive sweating, salivation, or tear production due to their cholinergic effects. Any neurological changes after mushroom consumption warrant immediate medical attention.

Organ-Specific Symptoms are a red flag for severe toxicity. Amatoxin-containing mushrooms, for instance, can cause liver and kidney damage, leading to symptoms like jaundice, dark urine, or swelling. Delayed treatment in such cases can result in liver failure or death. Similarly, mushrooms containing orellanine, such as the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius orellanus*), can cause kidney damage with symptoms like reduced urine output or back pain appearing days after ingestion. Monitoring for these signs is critical, as they indicate a medical emergency.

Systemic Symptoms such as rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, difficulty breathing, or loss of consciousness should never be overlooked. These can occur with mushrooms that affect the cardiovascular or respiratory systems, such as those containing toxins like coprine or gyromitrin. Even if symptoms seem mild initially, they can escalate rapidly, making it essential to seek medical help at the first sign of distress. Carrying a sample of the consumed mushroom for identification can aid healthcare providers in determining the appropriate treatment.

In conclusion, the risks of eating wild mushrooms are significant, and the early symptoms of poisoning can be subtle but life-threatening. Being vigilant for gastrointestinal, neurological, organ-specific, and systemic symptoms is key to ensuring prompt medical intervention. When in doubt, avoid consuming wild mushrooms altogether and consult experts or poison control centers for guidance. Remember, quick action can save lives.

Can You Eat Mushroom Stems? Safety Tips and Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Safe Foraging Practices: Follow expert guidelines to minimize risks while collecting wild mushrooms

Wild mushroom foraging can be a rewarding activity, but it comes with significant risks if not approached with caution and knowledge. Many wild mushrooms are toxic, and some can be deadly, making proper identification crucial. To minimize risks, it is essential to follow expert guidelines and adopt safe foraging practices. Start by educating yourself through reputable sources such as mycology books, local foraging clubs, or certified courses. Understanding the basics of mushroom anatomy, such as gills, spores, and stems, can aid in accurate identification. Always remember that relying on folklore or unverified methods, like the "color test" or "animal consumption test," can be misleading and dangerous.

One of the most critical safe foraging practices is to never consume a wild mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Even experienced foragers double-check their findings using field guides or expert consultation. Carry a notebook and document details like the mushroom’s habitat, color, size, and smell, as these characteristics are vital for identification. Avoid collecting mushrooms that are damaged, decaying, or infested with insects, as they may be difficult to identify or unsafe to eat. Additionally, always forage in areas free from pollution, such as roadsides or industrial zones, to prevent contamination.

Another key practice is to forage selectively and sustainably. Only collect what you need and leave the majority of mushrooms in their natural habitat to ensure ecological balance. Use a knife to cut mushrooms at the base rather than pulling them out, as this preserves the mycelium and allows the fungus to continue growing. Avoid foraging in protected areas or private property without permission. By respecting nature and local regulations, you contribute to the long-term health of mushroom populations and their ecosystems.

Proper handling and preparation are equally important after foraging. Clean mushrooms thoroughly to remove dirt and debris, but avoid washing them until you are ready to cook, as moisture can cause spoilage. If you are new to foraging, start by identifying and cooking commonly edible species like chanterelles or oyster mushrooms before attempting less familiar varieties. Always cook wild mushrooms before consuming them, as heat can neutralize certain toxins. If you experience any adverse symptoms after eating foraged mushrooms, seek medical attention immediately and bring a sample of the mushroom for identification.

Finally, join a local mycological society or connect with experienced foragers to enhance your skills and knowledge. Group foraging trips provide opportunities to learn from experts and verify your findings. Many regions also have poison control centers or mycologists who can assist with identification. By combining personal education, cautious practices, and community support, you can enjoy the benefits of wild mushroom foraging while significantly reducing the associated risks. Remember, the goal is not just to find mushrooms but to do so safely and responsibly.

Optimal Mushroom Capsule Dosage: A Guide to Safe Consumption

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$5.49 $6.67

Regional Mushroom Risks: Know local toxic species and their habitats to avoid accidental ingestion

Eating wild mushrooms can be a rewarding culinary adventure, but it comes with significant risks, especially if you’re unfamiliar with regional toxic species and their habitats. Regional Mushroom Risks vary widely because different areas harbor unique fungal ecosystems, each with its own set of edible and poisonous varieties. For instance, the Pacific Northwest in the United States is home to the deadly *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap), often found near oak trees, while the Eastern United States may host the toxic *Galerina marginata*, commonly growing on decaying wood. Understanding these regional differences is crucial to avoid accidental ingestion of harmful species.

To mitigate risks, know local toxic species by consulting field guides, mycological societies, or local experts. In Europe, the *Amanita virosa* (Destroying Angel) is a notorious killer, thriving in woodland areas, particularly under birch and coniferous trees. In Australia, the *Lepidella muscoda* (Poison Fire Coral) is a highly toxic species found in wet forests. Familiarize yourself with the appearance, habitat, and seasonality of these mushrooms to reduce the likelihood of mistaking them for edible varieties. Remember, some toxic mushrooms closely resemble safe ones, such as the *Amanita muscaria* (Fly Agaric) and edible *Amanita caesarea* (Caesar’s Mushroom).

Habitats play a critical role in identifying risky mushrooms. Toxic species often favor specific environments, such as deciduous forests, coniferous woods, or grassy areas. For example, the *Clitocybe dealbata* (Ivory Funnel) grows in lawns and gardens across Europe and North America, while the *Cortinarius rubellus* (Deadly Webcap) prefers coniferous forests in the UK. Learning these habitat preferences can help foragers avoid areas where dangerous mushrooms are likely to grow. Additionally, be cautious after periods of rain, as many toxic species flourish in wet conditions.

Regional climate and geography further influence mushroom distribution. In tropical regions like Southeast Asia, the *Podostroma cornu-damae* (Poison Fire Coral) is a highly toxic species found in mountainous areas. In contrast, arid regions may have fewer mushroom species overall, but those present could still include toxic varieties. Always research the specific risks associated with your location, as even neighboring regions can have vastly different fungal populations.

Finally, never rely solely on folklore or visual identification when foraging. Common myths, such as "toxic mushrooms always taste bad" or "animals avoid poisonous mushrooms," are unreliable and dangerous. Instead, adopt a cautious approach: if in doubt, leave it out. Joining local mycological clubs or workshops can provide hands-on learning and expert guidance. By knowing local toxic species and their habitats, you can enjoy the thrill of mushroom foraging while minimizing the risks of accidental ingestion.

Preparing Berkeley Polypore Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Culinary Guide

You may want to see also

Cooking and Preparation: Properly prepare wild mushrooms to reduce potential toxins and ensure safety

Eating wild mushrooms can be a rewarding culinary experience, but it comes with significant risks due to the presence of toxic species and potential contaminants. Proper cooking and preparation are essential to minimize these risks and ensure safety. While no method guarantees complete toxin removal, certain practices can reduce harmful substances and make consumption safer. Here’s how to approach the cooking and preparation of wild mushrooms with caution.

Identification and Sourcing: Before cooking, ensure the mushrooms are correctly identified by an expert. Misidentification is the leading cause of mushroom poisoning. Avoid mushrooms with uncertain identities, and never rely solely on online guides or apps. Once you’re certain of the species, source mushrooms from clean, unpolluted areas to prevent exposure to heavy metals, pesticides, or other environmental toxins. Mushrooms absorb contaminants easily, so avoid areas near roads, industrial sites, or agricultural fields.

Cleaning and Preparation: Thoroughly clean wild mushrooms to remove dirt, debris, and potential surface toxins. Gently brush off soil with a soft brush or damp cloth, avoiding excessive water absorption, as mushrooms are like sponges. If necessary, rinse them quickly under cold water and pat them dry. Trim any damaged or discolored parts, as these may harbor toxins or bacteria. Proper cleaning reduces the risk of ingesting harmful substances and ensures a better cooking outcome.

Cooking Methods to Reduce Toxins: Cooking wild mushrooms is crucial for breaking down certain toxins and making them safer to eat. Heat treatment can deactivate enzymes and destroy some toxic compounds. Always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly; never consume them raw. Boiling or simmering in water for at least 15–20 minutes is effective, as toxins can leach into the water, which should then be discarded. Alternatively, sautéing or frying at high temperatures for an extended period can also reduce toxin levels. Avoid consuming the cooking liquid, as it may contain concentrated toxins.

Additional Safety Measures: Even after proper cooking, some toxins may remain, so moderation is key. Start with small portions to test tolerance and watch for adverse reactions. Avoid serving wild mushrooms to children, pregnant women, or individuals with compromised immune systems, as they are more susceptible to poisoning. If in doubt, consult a mycologist or poison control center. Combining proper identification, careful cleaning, and thorough cooking significantly reduces the risks associated with eating wild mushrooms, but always prioritize caution.

Do Mushrooms Eat Ferns? Unraveling the Fungal-Plant Relationship

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Eating wild mushrooms can be extremely risky, as many species are toxic or deadly. Without proper identification by an expert, consuming wild mushrooms can lead to severe poisoning, organ failure, or even death.

No, appearance alone is not a reliable way to identify edible mushrooms. Many toxic species closely resemble safe ones, and even experienced foragers can make mistakes. Always consult an expert or use a trusted field guide.

There are no wild mushrooms that are universally safe for everyone. Even commonly edible species can cause allergic reactions or digestive issues in some people. Additionally, misidentification remains a significant risk.

Symptoms vary depending on the type of mushroom ingested but can include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, hallucinations, seizures, organ failure, and in severe cases, death. Symptoms may appear within minutes to hours after consumption.

No, cooking, boiling, or drying does not eliminate most mushroom toxins. Toxic compounds remain harmful even after preparation. Only consume wild mushrooms if you are 100% certain of their identification.