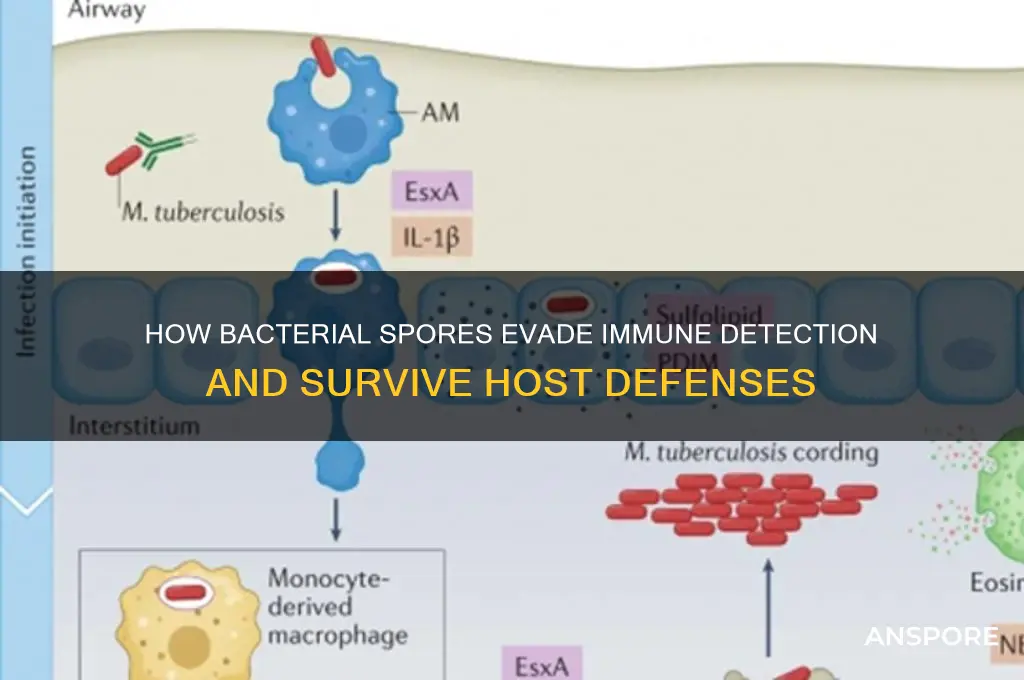

Spores play a crucial role in helping bacteria evade immune responses through several adaptive mechanisms. When environmental conditions become unfavorable, certain bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, form highly resistant endospores that can remain dormant for extended periods. These spores are encased in a protective layer that shields them from harsh conditions, including immune system attacks. Their robust outer coat, composed of proteins and peptidoglycan, resists phagocytosis and enzymatic degradation by immune cells. Additionally, spores lack metabolic activity, making them invisible to immune sensors that detect active pathogens. Once conditions improve, spores germinate into vegetative cells, allowing bacteria to re-establish infection without triggering a strong immune response. This survival strategy enables bacteria to persist in hostile environments and evade immune detection, posing challenges for treatment and eradication.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore coat composition resists immune cell recognition and phagocytosis

- Spores remain dormant, avoiding immune detection and response activation

- Spore surface proteins mask pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)

- Spores withstand antimicrobial peptides and enzymes produced by immune cells

- Spores evade complement system activation and immune cascade triggering

Spore coat composition resists immune cell recognition and phagocytosis

Bacterial spores are masters of survival, capable of enduring extreme conditions that would destroy their vegetative counterparts. One of their most remarkable strategies involves the spore coat, a multi-layered protective shell that not only shields the spore from physical and chemical stressors but also plays a pivotal role in evading the host immune system. The composition of the spore coat is uniquely tailored to resist immune cell recognition and phagocytosis, making it a critical component in the bacterium's immune evasion toolkit.

Consider the spore coat as a stealth suit, engineered to minimize detection by the immune system. Its outer layers are composed of proteins and polymers that lack the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) typically recognized by immune cells. For instance, the exosporium, the outermost layer of the spore coat in species like *Bacillus anthracis*, is rich in glycoproteins and polysaccharides that mask the underlying immunogenic components. This masking effect reduces the binding of opsonins—proteins that tag pathogens for phagocytosis—and diminishes the activation of complement pathways, which are crucial for immune cell recruitment and attack.

The spore coat’s resistance to phagocytosis is further enhanced by its structural integrity and surface properties. Phagocytic cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, rely on surface receptors to bind and internalize pathogens. However, the spore coat’s smooth, hydrophobic surface often lacks the adhesive properties needed for efficient phagocytic uptake. Studies have shown that spores of *Bacillus subtilis* and *Clostridium difficile* exhibit reduced phagocytosis rates compared to their vegetative forms, primarily due to the coat’s ability to repel immune cell attachment. Additionally, the coat’s cross-linked protein network provides mechanical strength, making it difficult for phagocytic cells to deform and engulf the spore.

Practical implications of this immune evasion strategy are particularly evident in clinical settings. For example, *C. difficile* spores can persist in hospital environments for months, resisting both disinfectants and the immune defenses of vulnerable patients. To mitigate this, healthcare facilities must employ stringent cleaning protocols, such as using sporicidal agents like chlorine bleach (at concentrations of 5,000–10,000 ppm) to disrupt the spore coat’s protective barrier. Similarly, in vaccine development, understanding the spore coat’s role in immune evasion has led to innovative approaches, such as engineering spore-based vaccines where the coat is modified to enhance immunogenicity without compromising stability.

In summary, the spore coat’s composition is a sophisticated defense mechanism that enables bacteria to evade immune detection and destruction. By masking immunogenic molecules, resisting phagocytic uptake, and maintaining structural integrity, the coat ensures the spore’s survival in hostile environments. For researchers and clinicians, unraveling the intricacies of this composition not only deepens our understanding of bacterial resilience but also informs strategies to combat spore-forming pathogens more effectively.

Black Mold Sporulation: Understanding the Timeline for Spore Development

You may want to see also

Spores remain dormant, avoiding immune detection and response activation

Bacterial spores are masters of survival, employing a strategy that hinges on dormancy to evade the immune system's vigilant surveillance. This dormant state, characterized by minimal metabolic activity and a robust, protective coat, allows spores to persist in hostile environments, including the human body, without triggering an immune response. Imagine a stealth mode for bacteria, where they become nearly invisible to the immune system's radar. This ability to remain dormant is not just a passive defense mechanism; it is an active strategy that ensures the bacterium's long-term survival and potential for future proliferation.

The spore's outer layers play a critical role in this immune evasion. Composed of proteins and peptides, these layers act as a barrier, shielding the spore's internal components from immune detection. For instance, the exosporium, the outermost layer, can contain glycoproteins that mimic host molecules, effectively disguising the spore as a non-threatening entity. This molecular mimicry is a sophisticated tactic, akin to a spy blending into a crowd by wearing a disguise. As a result, the immune system fails to recognize the spore as a foreign invader, allowing it to persist without eliciting an inflammatory response.

Consider the implications of this dormancy in clinical settings. Infections caused by spore-forming bacteria, such as *Clostridium difficile*, can be particularly challenging to treat. Spores can survive in hospital environments for extended periods, resisting disinfection efforts and waiting for the opportune moment to germinate and cause disease. For patients, especially the elderly or immunocompromised, this means a higher risk of recurrent infections. Practical measures, such as thorough environmental cleaning with sporicidal agents like chlorine bleach (at a concentration of 5,000–10,000 ppm), are essential to disrupt this cycle. Additionally, healthcare providers should be vigilant about hand hygiene, using alcohol-based rubs followed by soap and water to physically remove spores, as alcohol alone does not kill them.

From an evolutionary perspective, the spore's dormancy is a testament to the ingenuity of bacterial survival strategies. By remaining metabolically inactive, spores avoid producing the metabolic byproducts that typically alert the immune system to their presence. This is particularly advantageous in nutrient-poor or hostile environments, where rapid growth and replication are not feasible. For example, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, can form spores that survive in soil for decades, waiting for a suitable host to initiate infection. This long-term persistence highlights the spore's ability to outwait both environmental challenges and immune defenses.

In conclusion, the dormancy of bacterial spores is a key mechanism in their immune evasion strategy. By minimizing metabolic activity, adopting a protective coat, and employing molecular mimicry, spores effectively avoid detection and response activation by the immune system. Understanding this mechanism not only sheds light on bacterial survival tactics but also informs practical measures to prevent and control spore-related infections. Whether in healthcare settings or natural environments, recognizing the role of dormancy in immune evasion is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat these resilient microorganisms.

Can You Spot Spores Without a Microscope? The Naked Eye Test

You may want to see also

Spore surface proteins mask pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)

Bacterial spores are masters of deception, employing a sophisticated strategy to evade the immune system's vigilant surveillance. One of their cunning tactics involves the strategic deployment of spore surface proteins, which act as a disguise, concealing the telltale signs of bacterial invasion. These proteins are the key players in a molecular masquerade, effectively masking the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that would otherwise trigger a robust immune response.

The immune system relies on pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to identify PAMPs, which are essential molecular structures common to various pathogens. However, spore-forming bacteria have evolved a clever countermeasure. The spore surface proteins, through their unique composition and structure, interfere with the binding of PAMPs to PRRs, thereby preventing the activation of immune signaling pathways. This interference is akin to a molecular cloak, rendering the spores invisible to the immune system's radar. For instance, research has identified specific proteins in *Bacillus anthracis* spores that bind to immune cells, blocking the recognition of PAMPs and subsequently inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are crucial for mounting an effective immune response.

This immune evasion strategy is particularly critical during the early stages of spore germination, a vulnerable period when the emerging bacterium is susceptible to immune attack. By masking PAMPs, the spores buy time for the bacteria to establish an infection before the immune system can respond effectively. The success of this tactic is evident in the ability of spore-forming pathogens to cause persistent and often severe infections, such as anthrax and tetanus, where the immune system's delayed response contributes to the diseases' severity.

Understanding this mechanism has significant implications for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. For example, designing inhibitors that target these spore surface proteins could potentially unmask the PAMPs, allowing the immune system to recognize and combat the infection more efficiently. Furthermore, this knowledge can inform the creation of improved vaccines, where the inclusion of specific spore surface proteins might enhance the immune system's ability to identify and remember these cunning pathogens.

In the ongoing arms race between pathogens and the immune system, the study of spore surface proteins and their role in PAMP masking provides valuable insights. It highlights the intricate ways bacteria manipulate immune responses and offers potential targets for intervention, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective treatments and preventive measures against spore-forming bacterial infections.

Exploring Sports Opportunities in Peru's Universities: Programs and Facilities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores withstand antimicrobial peptides and enzymes produced by immune cells

Bacterial spores are remarkably resilient, capable of withstanding harsh conditions that would destroy their vegetative counterparts. Among their survival strategies is an innate resistance to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and enzymes produced by immune cells. These molecules, which are crucial components of the innate immune system, typically target and disrupt bacterial cell membranes or essential cellular processes. However, spores evade this defense mechanism through their unique structure and composition. The outer layer of a spore, known as the exosporium, is rich in proteins and lipids that act as a protective barrier, preventing AMPs from penetrating and exerting their antimicrobial effects. This structural fortification ensures that spores remain dormant and unscathed, even in the presence of immune-derived enzymes like lysozyme, which would otherwise degrade bacterial cell walls.

To understand this resistance, consider the mechanism of AMPs. These peptides, such as defensins and cathelicidins, typically insert into bacterial membranes, causing disruption and cell lysis. However, spores possess a highly cross-linked cortical layer beneath the exosporium, which is impermeable to most AMPs. Additionally, the spore coat contains enzymes like superoxide dismutase and catalase, which neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by immune cells. For instance, studies have shown that *Bacillus subtilis* spores can withstand concentrations of up to 100 μM of human β-defensin-2, a dosage lethal to vegetative cells. This resistance is not merely passive; it is an active defense system honed through evolutionary adaptation to hostile environments.

From a practical standpoint, this resistance has significant implications for infection control and treatment. Spores of pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis* can persist in clinical settings, evading standard disinfection protocols that rely on AMPs or enzymatic cleaners. For example, quaternary ammonium compounds (QUATs), commonly used in hospital disinfectants, are ineffective against spores due to their inability to penetrate the spore coat. To combat this, healthcare facilities must employ spore-specific decontamination methods, such as hydrogen peroxide vaporization or chlorine dioxide treatment, which can breach the spore’s protective layers. Understanding this resistance also highlights the need for novel antimicrobial strategies that target dormant spores, such as spore germination inhibitors or coat-degrading enzymes.

Comparatively, the resilience of spores to immune-derived enzymes like lysozyme and proteases underscores their evolutionary advantage. While these enzymes efficiently degrade the peptidoglycan and proteins of vegetative bacteria, spores remain impervious due to their modified cell wall structure and the presence of spore-specific proteins like SASPs (Small Acid-Soluble Spore Proteins). These proteins bind to DNA, protecting it from enzymatic degradation and further safeguarding the spore’s genetic material. This dual-layered defense—structural and biochemical—ensures that spores can survive in immune-active environments, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate and resume growth. For researchers and clinicians, this comparison highlights the need to develop targeted therapies that disrupt spore-specific defenses rather than relying on broad-spectrum antimicrobials.

In conclusion, the ability of spores to withstand antimicrobial peptides and enzymes produced by immune cells is a testament to their evolutionary sophistication. This resistance is not just a passive byproduct of their structure but an active defense system that ensures survival in hostile environments. For practitioners, understanding this mechanism is crucial for designing effective disinfection protocols and antimicrobial therapies. By targeting the unique vulnerabilities of spores, such as their germination process or coat integrity, we can develop strategies that neutralize these resilient forms and prevent bacterial persistence in clinical and environmental settings.

Can N95 Masks Effectively Block Mold Spores? Expert Insights

You may want to see also

Spores evade complement system activation and immune cascade triggering

Bacterial spores, particularly those of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade the host immune system, ensuring their survival and persistence. One of the most remarkable strategies involves their ability to resist complement system activation, a critical component of innate immunity. The complement system, comprising over 30 proteins, is designed to tag pathogens for destruction, promote inflammation, and directly lyse microbial cells. However, spores possess a unique outer layer, primarily composed of spore coat proteins and peptidoglycan, which acts as a stealth shield against complement recognition. This layer lacks the molecular patterns that typically trigger complement activation, allowing spores to remain invisible to this immune cascade.

To understand this evasion mechanism, consider the structure of the spore coat. It is rich in highly cross-linked proteins and lacks the negatively charged lipids found on bacterial cell membranes, which are known to attract complement proteins. For instance, the absence of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in spores prevents the binding of complement factor C1q, the initiator of the classical pathway. Additionally, the spore surface is resistant to opsonization by complement proteins like C3b, which would otherwise mark the spore for phagocytosis. This resistance is further enhanced by the spore’s ability to bind host proteins, such as fibrinogen and plasminogen, which can mask complement-activating sites and promote immune evasion.

From a practical standpoint, this immune evasion has significant implications for infection control and vaccine development. For example, *Bacillus anthracis* spores, the causative agent of anthrax, can persist in the environment for decades, evading immune detection until they germinate into vegetative cells. Understanding how spores resist complement activation could inform the design of spore-based vaccines, where controlled immune recognition is essential. Researchers are exploring surface modifications, such as introducing complement-activating ligands, to enhance the immunogenicity of spore-based vaccines. For instance, conjugating spores with C3b-coated nanoparticles has shown promise in animal models, increasing phagocytosis and immune response.

A comparative analysis reveals that while vegetative bacterial cells often rely on rapid replication and toxin production to outpace immune responses, spores adopt a more passive yet equally effective strategy. By minimizing immunogenic surface features and exploiting host proteins for camouflage, spores ensure long-term survival in hostile environments. This contrasts with the short-lived evasion tactics of vegetative cells, which are more prone to complement-mediated lysis. For clinicians and researchers, this distinction underscores the need for targeted therapies that disrupt spore-specific evasion mechanisms, such as inhibiting plasminogen binding to prevent immune masking.

In conclusion, the ability of spores to evade complement system activation and immune cascade triggering is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By leveraging a non-immunogenic surface and host protein binding, spores achieve stealth survival, posing challenges for both natural immunity and medical interventions. Practical applications of this knowledge range from improving vaccine efficacy to developing novel antimicrobial strategies. As research progresses, unraveling the molecular intricacies of spore-immune interactions will be key to combating spore-forming pathogens effectively.

Understanding Spore Prints: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Identification

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bacterial spores have a thick, protective outer layer that resists phagocytosis by immune cells and is resistant to antibodies, enzymes, and other immune components, allowing them to evade detection and destruction.

Yes, bacterial spores can survive inside phagocytic immune cells due to their dormant state and robust structure, which prevents degradation and allows them to persist until conditions are favorable for germination.

Spore dormancy reduces metabolic activity, making spores less recognizable to the immune system, as they do not produce antigens or toxins that typically trigger immune responses.

Spores can evade immune memory responses because their dormant state and unique structure differ from active bacterial cells, making it difficult for the immune system to recognize and mount an effective memory-based response.