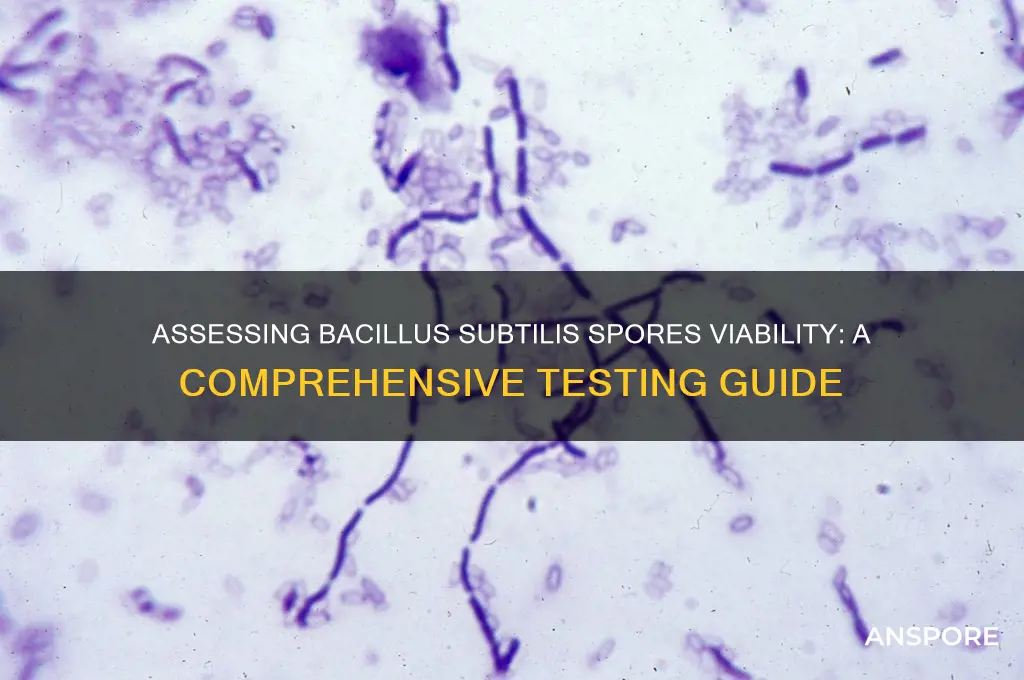

Checking the viability of *Bacillus subtilis* spores is crucial for ensuring their effectiveness in various applications, such as probiotics, biocontrol agents, or industrial processes. Viability can be assessed using several methods, including germination assays, where spores are exposed to nutrient-rich conditions to induce growth, and colony-forming unit (CFU) counts, which involve plating spores on agar media and counting the resulting colonies. Additionally, fluorescent staining techniques, such as using dyes like propidium iodide or SYTO 9, can differentiate between live and dead spores based on membrane integrity. Heat or chemical treatments, like exposure to ethanol or sodium hypochlorite, can also be used to eliminate non-viable spores before viability testing. Combining these methods provides a comprehensive assessment of spore viability, ensuring their functionality and reliability in downstream applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method | Germination Assay, Heat Resistance Test, Dye Exclusion Assay, CFU Counting |

| Germination Assay | Spores are incubated in nutrient-rich medium; viable spores germinate and grow into vegetative cells. |

| Heat Resistance Test | Spores are heated at 80°C for 10 minutes; viable spores survive and can be cultured. |

| Dye Exclusion Assay | Spores are stained with dyes like malachite green or CFU dyes; viable spores exclude dye, appearing colorless. |

| CFU Counting | Spores are plated on nutrient agar; viable spores form colonies (CFU/mL). |

| Microscopy | Phase-contrast or fluorescence microscopy to observe spore morphology and integrity. |

| Flow Cytometry | Spores are analyzed for size, granularity, and viability using fluorescent dyes. |

| PCR-Based Methods | Detection of specific DNA sequences in viable spores using PCR or qPCR. |

| Metabolic Activity Assay | Measurement of ATP production or enzyme activity in viable spores. |

| Storage Conditions | Spores remain viable for years when stored at -20°C or lyophilized. |

| Optimal Germination Conditions | Nutrient broth with L-valine or other germinants at 37°C. |

| Viability Range | Viable spores retain metabolic activity and can germinate under suitable conditions. |

| Inhibition Factors | High humidity, extreme temperatures, or exposure to UV light reduce viability. |

| Confirmation of Viability | Combination of multiple methods (e.g., CFU counting + dye exclusion) for accuracy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Staining Techniques: Simple, quick method to visualize spores under a microscope

- Germination Assays: Test spore viability by inducing germination in specific conditions

- Heat Shock Treatment: Apply heat to kill vegetative cells, leaving only viable spores

- Colony Counting Method: Plate spores on agar to count colonies formed by viable spores

- Fluorescence Viability Stains: Use dyes like FDA or CTC to detect metabolically active spores

Spore Staining Techniques: Simple, quick method to visualize spores under a microscope

Spores of *Bacillus subtilis* are renowned for their resilience, but confirming their viability requires precise visualization. Spore staining techniques offer a straightforward, time-efficient solution for this purpose. By employing specific dyes and protocols, these methods differentiate spores from vegetative cells, enabling researchers to assess their presence and condition under a microscope. This approach is particularly valuable in microbiology labs where rapid, accurate results are essential.

One widely adopted technique is the Wirtz-Conklin method, which uses a combination of malachite green as the primary stain and safranin as the counterstain. To perform this, heat-fix a smear of the bacterial culture on a slide and expose it to malachite green vapor for 10–15 minutes. This process allows the dye to penetrate the spore’s thick coat. After rinsing, decolorize the slide with water and apply safranin for 2–3 minutes to stain the vegetative cells. Under a microscope, viable spores appear as distinct, refractile, green bodies, while vegetative cells take on a pink hue. This contrast facilitates easy identification and enumeration.

While the Wirtz-Conklin method is effective, it requires careful handling of heat and dyes. An alternative is the Schaeffer-Fulton technique, which eliminates the need for steaming by directly applying malachite green to the smear for 5 minutes at 80°C. After cooling, rinse the slide, counterstain with safranin, and observe. This method is less time-consuming and reduces the risk of overheating the sample, making it suitable for beginners or high-throughput applications. Both techniques, however, rely on the spore’s resistance to decolorization, a key indicator of viability.

For those seeking a simpler, more cost-effective option, the cotton blue stain can be employed. This method involves staining the smear with cotton blue for 5 minutes, followed by gentle rinsing. Viable spores appear as bright blue, refractile structures against a lighter background. While less discriminatory than malachite green-based methods, cotton blue staining is ideal for quick assessments or educational settings where precision is secondary to ease of use.

In conclusion, spore staining techniques provide a rapid, reliable means to visualize *Bacillus subtilis* spores under a microscope. Whether using the Wirtz-Conklin, Schaeffer-Fulton, or cotton blue method, each approach offers unique advantages tailored to specific needs. By mastering these techniques, researchers can efficiently confirm spore viability, ensuring the integrity of their experiments and applications. Practical tips include maintaining consistent heating times, using fresh dyes, and optimizing slide preparation for clarity. With these tools, even novice microbiologists can achieve accurate, reproducible results.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Do Spores Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Germination Assays: Test spore viability by inducing germination in specific conditions

Spore germination assays provide a direct method to assess the viability of *Bacillus subtilis* spores by inducing them to return to their vegetative state under controlled conditions. This approach leverages the fact that viable spores can sense and respond to specific environmental cues, such as nutrient availability, temperature, and pH, by activating metabolic processes and breaking dormancy. By monitoring germination rates and efficiency, researchers can quantitatively determine the proportion of viable spores in a sample.

To perform a germination assay, prepare a spore suspension in distilled water or a minimal buffer solution, ensuring the concentration is standardized (e.g., 10^7–10^8 spores/mL). Transfer aliquots of the suspension into tubes containing germination-inducing agents, such as L-valine (10 mM), inositol (10 mM), or a rich medium like LB broth. Incubate the tubes at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 1–2 hours, as this temperature and agitation mimic optimal growth conditions for *B. subtilis*. Include a control without inducers to account for spontaneous germination.

During incubation, viable spores will germinate, leading to changes in optical density (OD) due to the resumption of metabolic activity. Measure the OD at 600 nm at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes) using a spectrophotometer. A significant increase in OD compared to the control indicates successful germination. For a more precise analysis, pair this with microscopy to observe morphological changes, such as the loss of refractivity and swelling of spores, confirming their transition to vegetative cells.

While germination assays are effective, they require careful optimization. Factors like inducer concentration, incubation time, and spore age can influence results. For instance, older spores may exhibit delayed or reduced germination rates. Additionally, ensure the spore suspension is free of vegetative cells, as their presence can skew results. Combining germination assays with other viability tests, such as heat resistance or plating on agar, enhances the reliability of the assessment.

In conclusion, germination assays offer a robust and quantitative approach to evaluating *Bacillus subtilis* spore viability by mimicking natural activation conditions. By carefully controlling variables and employing complementary techniques, researchers can accurately determine the proportion of viable spores, making this method invaluable in fields like microbiology, biotechnology, and environmental science.

Mastering Galactic Warfare: Strategies to Dominate Spore's Space Stage

You may want to see also

Heat Shock Treatment: Apply heat to kill vegetative cells, leaving only viable spores

Heat shock treatment is a precise and effective method to differentiate between vegetative cells and viable spores of *Bacillus subtilis*. By applying a controlled heat treatment, typically at 80°C for 10–15 minutes, vegetative cells are selectively killed due to their inability to withstand such temperatures. Spores, however, remain intact because of their robust, heat-resistant structure. This process isolates spores, allowing for subsequent viability testing without interference from vegetative cells. It’s a critical step in spore enumeration and quality control in industries like probiotics, agriculture, and biotechnology.

To implement heat shock treatment, begin by preparing a suspension of *Bacillus subtilis* in a suitable buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Ensure the suspension is well-mixed to distribute cells and spores evenly. Transfer aliquots of the suspension into heat-resistant tubes, and immerse them in a preheated water bath at 80°C. Maintain this temperature for 10–15 minutes, using a thermometer to monitor consistency. After treatment, immediately cool the tubes on ice to prevent accidental germination of spores. This rapid cooling step is essential to preserve spore integrity for further analysis.

While heat shock is straightforward, precision is key. Overheating or underheating can yield inaccurate results. For instance, temperatures above 85°C may damage spores, while temperatures below 75°C might fail to kill all vegetative cells. Additionally, the duration of heat exposure must be strictly controlled; extending beyond 15 minutes risks spore viability, while shorter times may leave vegetative cells alive. Always calibrate your equipment and use a timer to ensure accuracy. For large-scale applications, consider using a heat block or automated system to standardize the process.

A practical tip for researchers is to include positive and negative controls. A positive control, such as an untreated sample, confirms the presence of vegetative cells and spores. A negative control, treated with a spore-killing agent like autoclaving, ensures no false positives. After heat shock, plate the treated suspension onto nutrient agar and incubate at 37°C for 24–48 hours. Count the colonies to determine spore viability. Compare these results to the untreated control to validate the efficacy of the heat shock treatment. This method not only isolates spores but also provides a quantitative measure of their viability.

In conclusion, heat shock treatment is a powerful tool for assessing *Bacillus subtilis* spore viability. Its simplicity and specificity make it ideal for both laboratory and industrial settings. By adhering to precise temperature and time parameters, researchers can confidently isolate spores for further testing. Whether for academic research or commercial applications, mastering this technique ensures accurate and reliable results, paving the way for advancements in spore-based technologies.

Fruit Spores: Are They Harmful to Your Health?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Colony Counting Method: Plate spores on agar to count colonies formed by viable spores

The Colony Counting Method stands as a cornerstone technique for assessing the viability of *Bacillus subtilis* spores, offering a direct and quantifiable measure of their ability to germinate and form colonies. This method hinges on the principle that only viable spores can resume metabolic activity, grow, and produce visible colonies on nutrient-rich agar plates. By enumerating these colonies, researchers can estimate the concentration of viable spores in a sample, a critical parameter in fields ranging from microbiology to biotechnology.

To execute this method, begin by preparing a series of dilutions of the spore suspension to ensure that the number of colonies on the agar plate falls within a countable range—typically 30 to 300 colonies per plate. For instance, dilutions of 10^-4 to 10^-6 are commonly used for *Bacillus subtilis* spores. Heat-shock the spores at 80°C for 10 minutes to eliminate any vegetative cells, as *B. subtilis* spores are heat-resistant while vegetative cells are not. Next, plate 100 μL of each dilution onto nutrient agar plates, such as LB agar, and spread the suspension evenly using a sterile glass spreader. Incubate the plates at 37°C for 16–24 hours, allowing sufficient time for viable spores to germinate and form visible colonies.

The accuracy of colony counting relies on meticulous technique and adherence to best practices. Ensure that the agar plates are free of contaminants by using sterile techniques throughout the process. Avoid overcrowding by selecting dilutions that yield countable colonies; plates with too many colonies (confluent growth) or too few (<30) will yield unreliable results. Use a colony counter or a grid to systematically count colonies, and calculate the number of viable spores per unit volume by multiplying the average colony count by the dilution factor. For example, if a 10^-5 dilution yields 150 colonies, the spore concentration is 1.5 × 10^7 CFU/mL.

While the Colony Counting Method is robust, it is not without limitations. The method assumes that each colony arises from a single viable spore, but clumping or chaining of spores can lead to underestimation. Additionally, the method does not distinguish between spores with varying degrees of viability; a spore that forms a small, slow-growing colony may be less robust than one forming a large, rapidly growing colony. Despite these caveats, the Colony Counting Method remains a gold standard for its simplicity, reliability, and direct correlation between colony number and spore viability.

In practical applications, this method is invaluable for quality control in spore production, environmental monitoring, and research on spore biology. For instance, industries producing *B. subtilis* spores as probiotics or biocontrol agents rely on colony counting to ensure product efficacy. Researchers studying spore germination mechanisms or resistance traits also use this method to quantify the impact of experimental conditions on spore viability. By mastering the Colony Counting Method, scientists and practitioners can confidently assess the viability of *Bacillus subtilis* spores, underpinning advancements in both fundamental and applied microbiology.

How Do Ferns Reproduce? Unveiling the Role of Spores in Their Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Fluorescence Viability Stains: Use dyes like FDA or CTC to detect metabolically active spores

Fluorescence viability stains offer a precise and efficient method to assess the metabolic activity of *Bacillus subtilis* spores, a critical step in determining their viability. Among the most commonly used dyes are Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) and 5-Cyano-2,3-ditolyl Tetrazolium Chloride (CTC). These dyes penetrate the spore membrane and are hydrolyzed by active enzymes, producing a fluorescent signal that indicates metabolic activity. FDA, for instance, is cleaved by esterases into fluorescein, emitting a green fluorescence under blue light excitation. CTC, on the other hand, is reduced by dehydrogenase enzymes to formazan, a red precipitate detectable under brightfield or fluorescence microscopy. Both dyes are highly sensitive and can differentiate between viable, metabolically active spores and non-viable ones with remarkable accuracy.

To implement this technique, begin by preparing a spore suspension in a suitable buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), at a concentration of approximately 10^6 to 10^7 spores per mL. Add the FDA dye at a final concentration of 5–10 µg/mL or CTC at 5 mM, ensuring thorough mixing. Incubate the suspension at 37°C for 30–60 minutes to allow enzymatic activity to occur. For FDA, examine the sample under a fluorescence microscope with a blue excitation filter (450–490 nm), looking for green fluorescence. For CTC, use a red filter (530–560 nm) or brightfield microscopy to detect red formazan deposits. Spores exhibiting fluorescence or coloration are considered metabolically active and, therefore, viable.

While fluorescence viability stains are powerful tools, their application requires careful consideration. False negatives can occur if spores are in a dormant state or if the dye concentration is too low. Conversely, false positives may arise from non-specific binding or contamination. To mitigate these risks, include positive (known viable spores) and negative (heat-killed spores) controls in every experiment. Additionally, ensure the dyes are stored in the dark and used within their shelf life to maintain efficacy. For optimal results, combine this method with other viability assays, such as germination tests or plate counting, to cross-validate findings.

The choice between FDA and CTC depends on the experimental goals and available equipment. FDA is ideal for rapid assessment due to its quick hydrolysis and bright fluorescence, making it suitable for high-throughput screening. CTC, however, provides a more stable signal and is better for long-term observations or when fluorescence microscopy is not available. Both dyes are cost-effective and compatible with standard laboratory protocols, making them accessible for routine viability testing. By leveraging these fluorescence viability stains, researchers can efficiently and accurately determine the metabolic activity of *Bacillus subtilis* spores, ensuring the reliability of their experimental outcomes.

Understanding Spore Syringe Contents: A Comprehensive Guide to Quantity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The most common method is the viable plate count assay, where spores are heat-shocked to kill vegetative cells, diluted, plated on nutrient agar, and incubated to count colonies, indicating viable spores.

Heat treatment (e.g., 80°C for 10 minutes) kills vegetative cells but not spores, ensuring that only viable spores germinate and grow into colonies during the assay.

Yes, phase-contrast microscopy or fluorescent staining (e.g., with dyes like propidium iodide) can assess spore integrity, but it does not confirm metabolic activity or germination ability.

Germination medium (e.g., nutrient broth or L-alanine) is used to induce spore germination. Viable spores will germinate and grow, while non-viable spores remain dormant.

Results from plating methods typically take 24–48 hours of incubation at 37°C, depending on the growth rate of Bacillus subtilis.