Checking for spore contamination in bacterial cultures is crucial to ensure the purity and integrity of the desired bacterial strain. Spores, particularly from spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium, are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals, making them difficult to eliminate once introduced. Contamination can lead to inaccurate experimental results, compromised research outcomes, or even safety risks in industrial applications. To detect spore contamination, several methods can be employed, including visual inspection for changes in colony morphology, Gram staining to identify spore-forming bacteria, and the use of selective media that inhibit spore-forming organisms while allowing the target bacteria to grow. Additionally, heat treatment or prolonged incubation at elevated temperatures can be used to selectively kill vegetative cells, leaving behind spores for identification. Early detection and proper handling are essential to prevent the spread of contamination and maintain the reliability of the culture.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | Look for cloudy or turbid areas in the culture, which may indicate spore formation. Spores can also appear as granular or clumped structures under a microscope. |

| Gram Staining | Spores appear as refractile, oval bodies within the bacterial cell. They are typically Gram-positive, but the surrounding vegetative cell may be Gram-negative. |

| Heat Shock Treatment | Incubate a portion of the culture at 80°C for 10-15 minutes. If spores are present, they will survive and germinate upon return to optimal growth conditions, leading to visible growth. |

| Spore Stain (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton) | Spores stain green with malachite green, while the vegetative cell stains red with safranin. This method specifically identifies endospores. |

| Phase-Contrast Microscopy | Spores appear as bright, refractile bodies within the bacterial cell due to their high refractive index. |

| Cultural Characteristics | Some spore-forming bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) produce distinct colony morphologies, such as rough or irregular edges, which may suggest spore contamination. |

| Biochemical Tests | Spores may exhibit different biochemical properties compared to vegetative cells. For example, spore-specific enzymes or metabolic activities can be tested. |

| Molecular Methods (PCR) | Target spore-specific genes (e.g., spo0A in Bacillus) using PCR to detect the presence of spore-forming bacteria. |

| Time to Detection | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, so contamination may not be immediately apparent. Repeated subculturing or prolonged incubation may be necessary to detect spore germination. |

| Selective Media | Use media that inhibits vegetative cell growth while allowing spore germination (e.g., heat-treated or enriched media) to isolate and confirm spore contamination. |

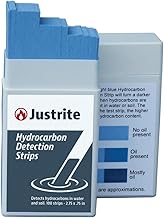

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Visual Inspection: Look for discoloration, fuzzy growth, or unusual textures indicating spore contamination

- Microscopic Examination: Use a microscope to identify spore structures distinct from bacterial cells

- Sporulation Tests: Incubate cultures at elevated temperatures to induce spore formation for detection

- Antibiotic Sensitivity: Test resistance to spore-specific antibiotics to confirm contamination presence

- PCR Assays: Use DNA-based methods to detect spore-specific genes in the culture

Visual Inspection: Look for discoloration, fuzzy growth, or unusual textures indicating spore contamination

A trained eye can often detect spore contamination in bacterial cultures through visual inspection alone. Discoloration is a key indicator, as bacterial colonies typically exhibit consistent pigmentation specific to the strain. Any deviation from the expected color—whether darker, lighter, or entirely different hues—warrants scrutiny. For instance, *Bacillus* spores may introduce a yellowish or brown tint, distinct from the creamy white of *E. coli*. Pair this observation with other signs for a more accurate assessment.

Fuzzy or cotton-like growth is another telltale sign of spore contamination. Unlike the smooth, defined edges of healthy bacterial colonies, spore-forming contaminants often produce filamentous or irregular textures. This "fuzzy" appearance results from the rapid proliferation of spore-forming organisms like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, which thrive in nutrient-rich agar environments. If you notice such growth, especially at the periphery of the plate, it’s time to investigate further.

Unusual textures, such as slimy or granular surfaces, can also signal spore contamination. Bacterial cultures should generally appear moist but not wet or gritty. A slimy texture may indicate the presence of spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis*, which produce biofilms as they mature. Conversely, a granular texture could suggest the growth of fungal spores, which often form clusters or aggregates. Document these observations carefully, as they provide critical clues for identifying the contaminant.

To perform an effective visual inspection, use proper lighting and magnification. Hold the culture plate at eye level under a bright, uniform light source to detect subtle color changes. For textured anomalies, a handheld magnifying glass (10x magnification) can reveal details invisible to the naked eye. Regularly compare the culture to a known uncontaminated sample of the same strain to establish a baseline. Early detection through visual inspection not only saves time but also prevents cross-contamination in shared lab spaces.

Can High-Proof Alcohol Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores? Find Out

You may want to see also

Microscopic Examination: Use a microscope to identify spore structures distinct from bacterial cells

Spore contamination in bacterial cultures can derail experiments, skew results, and waste valuable resources. Microscopic examination offers a direct, cost-effective method to identify these intruders. Unlike bacterial cells, spores exhibit distinct morphological features under magnification, making them detectable even in early stages of contamination.

A 1000x magnification oil-immersion lens is ideal for this task, revealing the characteristic oval or spherical shape of spores, typically 0.5 to 1.5 micrometers in diameter. Their refractile nature, often appearing as bright, phase-dark structures against the bacterial cytoplasm, further aids identification.

Technique: Prepare a wet mount of your culture by placing a small sample on a microscope slide, covering it with a coverslip, and sealing the edges with petroleum jelly to prevent drying. Focus on areas with lower bacterial density for clearer visualization. Look for structures that differ in size, shape, and refractive properties from the surrounding bacteria. Spores may appear singly or in chains, depending on the contaminating species.

Caution: Distinguishing spores from cellular debris or precipitated media components can be challenging. Familiarity with the expected morphology of your target bacteria and common contaminant spores is crucial. Consulting reference images or seeking guidance from experienced microbiologists can be invaluable.

Takeaway: Microscopic examination is a powerful tool for early detection of spore contamination. While it requires practice and a keen eye, its simplicity and accessibility make it a valuable technique for any laboratory dealing with bacterial cultures. Regular monitoring, especially during critical stages of experimentation, can prevent costly setbacks and ensure the integrity of your results.

Cryptococcus: Unveiling the Truth About Spores in This Fungal Pathogen

You may want to see also

Sporulation Tests: Incubate cultures at elevated temperatures to induce spore formation for detection

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, can withstand extreme conditions, making them a persistent threat to culture purity. Detecting their presence is crucial, and sporulation tests offer a targeted approach. This method leverages the fact that many spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, increase spore production under stress, including elevated temperatures. By incubating cultures at temperatures above their optimal growth range, typically 37°C to 45°C for 24 to 48 hours, researchers can induce sporulation, making spores more detectable through subsequent staining or microscopy techniques.

The process begins with inoculating a nutrient-rich medium, such as nutrient agar or tryptic soy broth, with the bacterial culture in question. After incubation at the elevated temperature, the culture is examined for morphological changes indicative of sporulation. For instance, *Bacillus* species often form endospores visible as bright, refractile bodies within the bacterial cells when stained with malachite green or safranin. These spores appear as oval or round structures under a light microscope, distinct from the vegetative cells. This visual confirmation is a critical step in identifying spore contamination.

While sporulation tests are effective, they require careful execution. Overheating or prolonged incubation can kill both vegetative cells and spores, leading to false-negative results. Conversely, insufficient temperature or time may fail to induce sporulation, resulting in false negatives. Researchers must also consider the specific sporulation requirements of the target bacteria, as some species may require additional stressors, such as nutrient deprivation or pH changes, to initiate spore formation. For example, *Clostridium* species often sporulate more efficiently in anaerobic conditions, necessitating the use of anaerobic jars or chambers during incubation.

A practical tip for enhancing detection accuracy is to perform a parallel control culture incubated at the organism’s optimal temperature (e.g., 37°C for most mesophiles). Comparing the control to the heat-stressed culture highlights sporulation-induced changes more clearly. Additionally, combining sporulation tests with molecular methods, such as PCR targeting spore-specific genes (e.g., *spo0A* in *Bacillus*), can provide a more definitive confirmation of spore presence, especially in mixed cultures where morphological identification is challenging.

In conclusion, sporulation tests are a powerful tool for detecting spore contamination in bacterial cultures. By strategically applying elevated temperatures to induce spore formation, researchers can visualize and confirm the presence of spores with relative ease. However, success hinges on precise control of incubation conditions and an understanding of the target bacteria’s sporulation requirements. When paired with complementary techniques, this method ensures robust detection, safeguarding culture integrity in both research and industrial settings.

Exploring the Size and Scope of Spore's Expansive DLC Content

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Antibiotic Sensitivity: Test resistance to spore-specific antibiotics to confirm contamination presence

Spore contamination in bacterial cultures can be insidious, often going unnoticed until it compromises experimental results. One of the most definitive ways to confirm the presence of spores is by testing resistance to spore-specific antibiotics. Spores, particularly those from Bacillus and Clostridium species, are notoriously resistant to many antibiotics due to their dormant, protective structure. Leveraging this resistance can serve as a diagnostic tool to identify contamination.

To perform an antibiotic sensitivity test, begin by preparing a bacterial culture on a solid agar medium, such as nutrient agar. Once the culture is established, use a sterile swab to inoculate a Mueller-Hinton agar plate, which is commonly used for antibiotic susceptibility testing. Next, apply spore-specific antibiotics, such as rifampicin (10–30 µg/mL) or vancomycin (5–30 µg/mL), to the plate using antibiotic discs or by creating a gradient with an antibiotic-infused strip. Incubate the plate at 37°C for 18–24 hours. If the culture exhibits resistance to these antibiotics, characterized by visible growth around the discs or within the gradient zone, it strongly suggests spore contamination.

A critical caution is to ensure the antibiotics used are specific to spore-forming bacteria. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may yield false negatives, as they could inhibit non-spore-forming bacteria while leaving spores unaffected. Additionally, control plates without antibiotics should be included to confirm the viability of the culture and rule out other inhibitory factors. This method is particularly useful in research settings where precision is paramount, such as in pharmaceutical or microbiological studies.

The takeaway is that antibiotic sensitivity testing is a targeted, reliable method to confirm spore contamination. By focusing on spore-specific resistance patterns, researchers can quickly identify and address contamination, preserving the integrity of their cultures. This approach not only saves time but also prevents the propagation of misleading data, making it an indispensable tool in the microbiologist’s arsenal.

Mastering Spore: Quick Tips to Access Commands Efficiently

You may want to see also

PCR Assays: Use DNA-based methods to detect spore-specific genes in the culture

Spore contamination in bacterial cultures can derail experiments, waste resources, and compromise results. PCR assays offer a precise, DNA-based solution by targeting spore-specific genes, providing a sensitive and specific detection method. Unlike traditional microscopy or plating techniques, PCR can identify spores even at low concentrations, making it ideal for early contamination detection.

To implement this method, begin by extracting DNA from your bacterial culture using a kit or protocol optimized for spore-rich samples. Spore coats are notoriously tough, so mechanical lysis (e.g., bead beating) or enzymatic treatment (e.g., lysozyme and proteinase K) may be necessary to ensure complete DNA release. Once extracted, design primers targeting conserved spore-specific genes, such as those encoding sporulation proteins (e.g., *spo0A* or *cotB* in *Bacillus* species). These genes are unique to spore-forming bacteria, minimizing false positives.

The PCR reaction itself follows standard protocols: denaturation at 95°C, annealing at 55–60°C (depending on primer Tm), and extension at 72°C. Use a high-fidelity polymerase to ensure accuracy, especially if sequencing is planned. Include positive (known spore DNA) and negative (sterile water) controls to validate the assay. For quantitative analysis, consider qPCR, which provides spore load estimates by measuring cycle threshold (Ct) values. A Ct value below 35 typically indicates significant contamination, though this threshold may vary by species and primer efficiency.

While PCR assays are powerful, they are not without limitations. False negatives can occur if spores are present but DNA extraction is incomplete, and false positives may arise from non-specific primer binding. To mitigate these risks, optimize extraction protocols and validate primer specificity using BLAST searches. Additionally, PCR detects DNA from both viable and non-viable spores, so complement this method with viability assays (e.g., propidium monoazide treatment) if distinguishing live spores is critical.

In conclusion, PCR assays provide a robust, DNA-based approach to detecting spore contamination in bacterial cultures. By targeting spore-specific genes, this method offers sensitivity and specificity unmatched by traditional techniques. With careful optimization and validation, PCR can become a cornerstone of contamination monitoring, ensuring the integrity of your experiments and saving time and resources in the long run.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Legal in Texas? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spore contamination often appears as cloudy, granular, or cotton-like patches in the culture, sometimes with a different texture or color compared to the desired bacterial growth. Spores may also form distinct colonies or clumps that resemble mold.

Perform a Gram stain to check for spore-forming bacteria, which appear as refractile, oval bodies within or outside the cells. Additionally, heat-shock the culture at 80°C for 10 minutes; spore-forming bacteria will survive, while most non-spore-forming bacteria will die.

Spore contamination often originates from the environment, such as soil, dust, or unsterilized equipment. It can also come from contaminated media, water, or improper sterilization techniques.

Use sterile techniques, autoclave all media and equipment, and filter-sterilize liquids. Regularly clean the workspace, use laminar flow hoods, and avoid exposing cultures to open air. Additionally, store cultures properly and use antibiotics or selective media when appropriate.