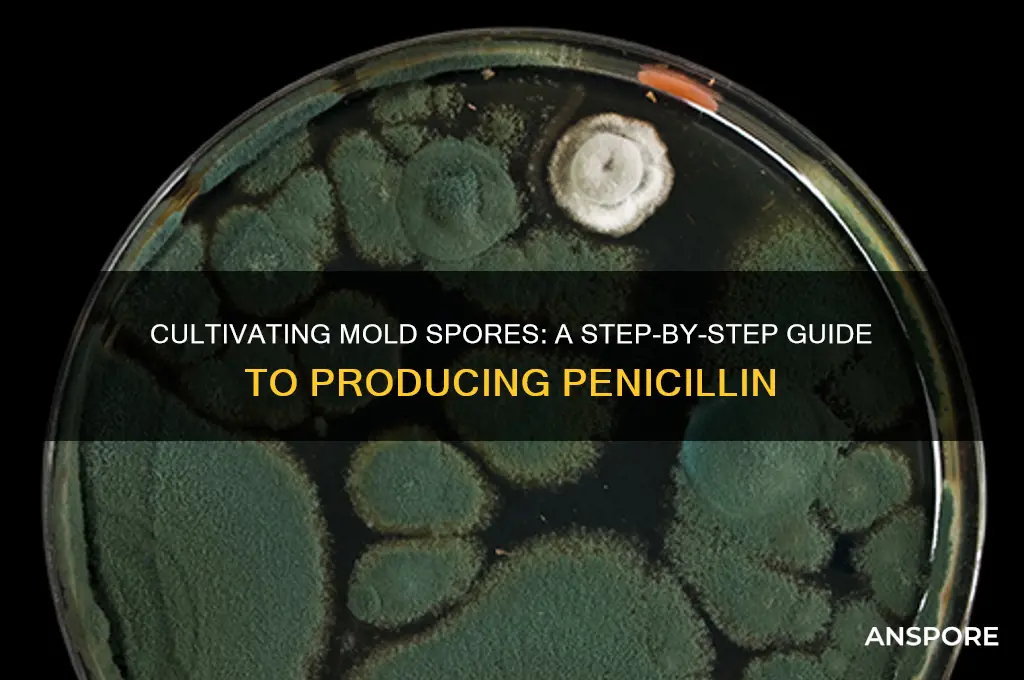

Culturing and processing mold spores for penicillin production is a fascinating and historically significant process that revolutionized modern medicine. It begins with isolating *Penicillium* fungi, typically *Penicillium chrysogenum* or *P. notatum*, from natural sources like soil or decaying organic matter. The spores are then cultured in a nutrient-rich medium, such as agar plates or liquid broths, under controlled conditions to encourage growth. Once the mold has proliferated, it is transferred to larger fermentation vessels where it produces penicillin as a secondary metabolite. The fermentation process is carefully monitored to optimize yield, and the resulting broth is filtered to separate the mold biomass from the penicillin-containing liquid. Subsequent steps involve extraction, purification, and concentration to obtain the antibiotic in a usable form. This intricate process, pioneered by Alexander Fleming and later scaled up by scientists like Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, remains a cornerstone of antibiotic production, highlighting the intersection of microbiology, chemistry, and biotechnology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mold Species | Penicillium chrysogenum (formerly P. notatum) is the primary species used for penicillin production. |

| Growth Medium | Nutrient-rich broth or agar containing sugars (e.g., lactose, glucose), nitrogen sources (e.g., corn steep liquor, peptone), and mineral salts. pH 5.0–7.0. |

| Inoculation | Spores are inoculated into sterile medium via aseptic techniques (e.g., flame sterilization, laminar flow hood). |

| Incubation Conditions | Temperature: 24–28°C (75–82°F); Aeration: Shaken or stirred for optimal oxygen transfer; Duration: 7–14 days for spore growth and penicillin production. |

| Fermentation Scale | Starts in small flasks (laboratory scale) and scales up to bioreactors (industrial scale) for mass production. |

| Penicillin Extraction | Mycelium is separated from broth via filtration. Penicillin is extracted using organic solvents (e.g., butyl acetate) and purified through precipitation or chromatography. |

| Sterilization | Medium and equipment sterilized via autoclaving (121°C, 15–20 minutes) to prevent contamination. |

| Contamination Prevention | Aseptic techniques, antibiotic additives (e.g., streptomycin), and regular monitoring of cultures. |

| Yield Optimization | Factors like pH, temperature, aeration, and nutrient concentration are optimized to maximize penicillin yield. |

| Strain Improvement | Mutagenesis and genetic engineering are used to enhance penicillin-producing strains. |

| Quality Control | Penicillin concentration and purity are tested using HPLC, bioassays, and antimicrobial activity tests. |

| Storage | Spores stored in glycerol at -80°C or lyophilized for long-term preservation. Penicillin stored in refrigerated, sterile conditions. |

| Safety Precautions | Personal protective equipment (PPE), proper ventilation, and adherence to biosafety guidelines to handle mold and penicillin. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sterile Techniques: Maintaining aseptic conditions to prevent contamination during mold spore cultivation

- Nutrient Media Preparation: Formulating agar or broth media for optimal mold growth

- Sporulation Induction: Techniques to encourage mold spore production for penicillin synthesis

- Fermentation Process: Scaling up mold cultivation for large-scale penicillin extraction

- Extraction & Purification: Isolating penicillin from mold cultures using filtration and chromatography

Sterile Techniques: Maintaining aseptic conditions to prevent contamination during mold spore cultivation

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of mold spore cultivation for penicillin production. A single unwanted microbe can outcompete your desired mold, rendering your efforts futile. Sterile techniques are your armor in this battle, a meticulous dance of precision and vigilance to maintain aseptic conditions.

Every step, from preparing your growth medium to transferring spores, demands unwavering attention to detail.

Imagine your workspace as a surgical theater. Cleanliness is paramount. Begin by sterilizing all equipment – Petri dishes, inoculating loops, and even your work surface – using an autoclave, a pressure cooker designed to kill all microorganisms. For smaller items, a flame from a Bunsen burner can be used for quick sterilization, but exercise extreme caution to avoid burns. Remember, heat is your ally in this process.

Allow sterilized equipment to cool before use, as heat can damage delicate spores.

The air itself is a potential carrier of contaminants. Work in a laminar flow hood, a specialized cabinet that creates a sterile airflow, pushing contaminants away from your work area. If a hood is unavailable, create a makeshift sterile environment by working near an open flame, which helps to reduce airborne microbes. However, this method is less reliable and requires even greater vigilance.

Always handle cultures with sterile instruments, never touching the growth medium directly.

Techniques like the streak plate method are essential for isolating pure mold colonies. This involves carefully streaking a small sample of spores across the surface of a nutrient agar plate, allowing individual colonies to grow separately. Incubate plates at the optimal temperature for your mold species, typically around 25°C (77°F), and monitor for growth. Select the most robust colonies for further cultivation, ensuring the purity of your penicillin-producing mold.

Maintaining aseptic conditions is a constant battle against the invisible. It requires patience, precision, and a healthy dose of paranoia. Every step, from sterilization to incubation, must be executed with meticulous care. Remember, the success of your penicillin production hinges on your ability to create and maintain a sterile environment, allowing your desired mold to flourish uncontested.

Effective Furniture Cleaning Tips to Eliminate Mold Spores Safely

You may want to see also

Nutrient Media Preparation: Formulating agar or broth media for optimal mold growth

The foundation of successful mold cultivation for penicillin production lies in crafting a nutrient media that mimics the mold's natural environment while providing essential resources for growth. This delicate balance requires careful selection and formulation of agar or broth media, considering factors like nutrient composition, pH, and sterility.

Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, solidifies the media, allowing for surface growth and easier observation of mold colonies. Broth, a liquid medium, promotes submerged growth and can be advantageous for large-scale production. The choice between agar and broth depends on the specific mold strain, desired growth characteristics, and downstream processing requirements.

Formulating the media involves a precise blend of carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Glucose, sucrose, or starch often serve as carbon sources, fueling mold metabolism. Nitrogen sources like peptone, yeast extract, or ammonium salts are crucial for protein synthesis and enzyme production. Trace elements like magnesium, potassium, and phosphorus are essential cofactors for various biochemical reactions. A typical agar media recipe for penicillin-producing molds might include: 20g agar, 20g glucose, 5g peptone, 2g yeast extract, 1g KH2PO4, 0.5g MgSO4·7H2O, and distilled water to 1 liter, adjusted to pH 6.5-7.0. Sterilization by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes ensures a contaminant-free environment.

It's crucial to note that media composition can significantly impact penicillin yield. Optimizing nutrient concentrations through trial and error, considering factors like mold strain specificity and desired growth rate, is essential for maximizing production. Additionally, maintaining sterile conditions throughout media preparation and handling is paramount to prevent contamination by competing microorganisms.

Beyond the basic components, additives can further enhance mold growth and penicillin production. Corn steep liquor, a byproduct of corn processing, provides vitamins and growth factors, while lactose can induce penicillin biosynthesis in some strains. Experimentation with different additives and their concentrations can lead to significant improvements in yield.

Mastering nutrient media preparation is a critical step in cultivating mold for penicillin production. By understanding the mold's nutritional requirements and employing careful formulation techniques, researchers and enthusiasts can create an optimal environment for robust mold growth and maximize the potential for penicillin yield.

Spores Unveiled: Exploring Varieties and Their Impact on Human Life

You may want to see also

Sporulation Induction: Techniques to encourage mold spore production for penicillin synthesis

Mold sporulation is a critical phase in penicillin production, as it directly impacts the yield and quality of the antibiotic. To maximize spore production, researchers and cultivators employ specific techniques that manipulate environmental conditions and nutrient availability. One effective method is nutrient limitation, particularly the reduction of nitrogen sources in the growth medium. When nitrogen becomes scarce, *Penicillium* species, such as *P. chrysogenum*, respond by diverting energy toward sporulation as a survival mechanism. For instance, a medium containing 1% glucose and 0.1% ammonium sulfate can induce sporulation within 72 hours, compared to richer media that promote vegetative growth. This technique underscores the principle that stress triggers spore formation, a key insight for optimizing penicillin synthesis.

Another powerful approach is osmotic stress induction, achieved by adding osmotic agents like sodium chloride or glycerol to the culture medium. A concentration of 0.5 M sodium chloride has been shown to significantly enhance spore production in *Penicillium* cultures, as the mold responds to the stress by forming spores to protect its genetic material. However, caution must be exercised, as excessive osmotic pressure can inhibit growth altogether. Balancing stress levels is crucial; for example, a gradual increase in salt concentration over 24 hours allows the mold to adapt and sporulate efficiently. This method highlights the delicate interplay between stress and survival in mold cultivation.

Physical factors also play a pivotal role in sporulation induction. Lowering the incubation temperature from the optimal 25°C to 20°C can stimulate spore formation, as cooler conditions mimic environmental stress and signal the mold to prepare for dispersal. Similarly, adjusting pH levels—ideally to a slightly acidic range of 5.5–6.0—can further enhance sporulation. These adjustments require precision, as extreme temperatures or pH values can halt growth. For instance, a study found that cultures maintained at 20°C and pH 5.8 produced 30% more spores than those at 25°C and pH 7.0, demonstrating the importance of fine-tuning environmental parameters.

Finally, aeration and agitation are essential techniques to promote sporulation. Molds like *Penicillium* are aerobic organisms, and increasing oxygen availability through vigorous shaking or aerated fermentation systems encourages spore development. In bioreactors, an aeration rate of 1 vvm (volume of air per volume of medium per minute) has been shown to optimize spore production while preventing the formation of clumps that could hinder penicillin extraction. This method not only boosts sporulation but also ensures uniform growth, a critical factor for industrial-scale production. By combining these techniques—nutrient limitation, osmotic stress, physical adjustments, and aeration—cultivators can systematically enhance mold spore production, laying the foundation for efficient penicillin synthesis.

Is Milky Spore Safe for Your Lawn and Garden? Find Out

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.79

Fermentation Process: Scaling up mold cultivation for large-scale penicillin extraction

Scaling up mold cultivation for large-scale penicillin extraction requires a meticulous fermentation process that balances precision, efficiency, and scalability. At its core, this process involves optimizing conditions for *Penicillium chrysogenum* (formerly *P. notatum*) to produce maximum penicillin while minimizing contamination. Industrial fermentation begins with selecting high-yielding strains, often genetically modified for enhanced productivity, and inoculating them into a nutrient-rich medium. This medium typically contains sugars (e.g., lactose or glucose), mineral salts, and precursors like phenylacetic acid to boost penicillin synthesis. The fermentation vessel, or bioreactor, must maintain strict parameters: a temperature of 24–28°C, pH 6.5–7.0, and dissolved oxygen levels above 30% saturation to support aerobic growth. Stirring speeds and aeration rates are critical, as inadequate mixing can lead to oxygen deprivation, while excessive agitation may damage the mycelium.

One of the key challenges in scaling up is ensuring uniform conditions across larger volumes. In small-scale lab settings, a 500 mL flask might suffice, but industrial production uses bioreactors ranging from 10,000 to 200,000 liters. To address this, engineers employ advanced monitoring systems, such as pH and oxygen probes, coupled with automated control mechanisms. For instance, foam formation, a common issue in large-scale fermentation, is managed using antifoam agents or mechanical breakers to prevent overflow and oxygen transfer inefficiencies. Additionally, the fermentation duration is optimized—typically 7 to 10 days—to maximize penicillin yield before the mold enters the stationary phase, where productivity declines. Post-fermentation, the broth contains penicillin at concentrations of 50–100 g/L, which is then extracted through filtration, precipitation, and purification steps.

A comparative analysis of batch versus continuous fermentation reveals distinct advantages and trade-offs. Batch fermentation, the traditional method, is simpler to implement but suffers from downtime between cycles. Continuous fermentation, on the other hand, offers higher productivity by maintaining a steady-state culture, but it requires sophisticated equipment and precise control to prevent contamination. For large-scale penicillin production, hybrid systems combining elements of both methods are increasingly popular. These systems use a series of interconnected bioreactors, allowing for continuous operation while minimizing the risk of batch-to-batch variability. This approach can increase penicillin output by up to 30% compared to conventional batch processes.

Practical tips for successful scaling include rigorous sterilization protocols, as even trace contaminants can outcompete the mold. Autoclaving the medium and bioreactor at 121°C for 20–30 minutes is standard practice. Another critical aspect is strain maintenance: regularly subculturing the mold on agar slants ensures genetic stability and prevents degeneration. For cost-effectiveness, by-products like mycelial biomass can be repurposed as animal feed or biofertilizer, reducing waste and improving sustainability. Finally, pilot-scale trials are indispensable for identifying bottlenecks before full-scale implementation. By simulating industrial conditions on a smaller scale, manufacturers can fine-tune parameters and avoid costly errors during production.

In conclusion, scaling up mold cultivation for penicillin extraction is a complex but achievable endeavor. It demands a blend of biological insight, engineering precision, and operational efficiency. From strain selection to bioreactor design, every step must be optimized to meet the global demand for this life-saving antibiotic. With advancements in biotechnology and process control, the fermentation process continues to evolve, promising higher yields, lower costs, and greater accessibility for penicillin worldwide.

Exploring the Astonishing Spore Production of Fungi: A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Extraction & Purification: Isolating penicillin from mold cultures using filtration and chromatography

The extraction and purification of penicillin from mold cultures is a delicate process that hinges on two primary techniques: filtration and chromatography. Once the mold, typically *Penicillium chrysogenum*, has been cultured and allowed to produce penicillin in a nutrient-rich broth, the first step is to separate the antibiotic from the mycelium and other cellular debris. Filtration serves as the initial purification method, where the fermented broth is passed through a series of filters to remove solid particles. A coarse filter captures larger mold fragments, while a finer filter, such as a 0.22-micron membrane, ensures the removal of smaller contaminants. This step is critical, as residual mold can interfere with subsequent purification stages and compromise the final product’s purity.

Following filtration, chromatography becomes the cornerstone of isolating penicillin from other compounds in the broth. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is commonly employed due to its precision and scalability. The filtered broth is injected into the chromatography system, where it is separated based on the differential affinity of molecules to the stationary phase. Penicillin, with its unique chemical properties, binds and elutes at a distinct time, allowing for its isolation. The mobile phase, often a carefully calibrated buffer solution, is chosen to optimize penicillin’s separation from impurities like proteins, sugars, and secondary metabolites. This step requires meticulous attention to pH, temperature, and flow rate to ensure maximum yield and purity.

A practical tip for researchers is to monitor the chromatography process using UV-Vis spectroscopy, as penicillin absorbs strongly at 260 nm. This real-time analysis allows for immediate adjustments to the system, ensuring the target compound is effectively isolated. Once collected, the penicillin fraction undergoes further concentration, typically through rotary evaporation under reduced pressure, to remove residual solvents and water. The resulting product is then lyophilized (freeze-dried) to yield a stable, powdered form of penicillin suitable for pharmaceutical use.

While filtration and chromatography are powerful tools, they are not without challenges. Contamination at any stage can render the entire batch unusable, emphasizing the need for sterile conditions and rigorous quality control. Additionally, the cost and technical expertise required for HPLC can be prohibitive for small-scale operations. For those with limited resources, alternative methods like ion-exchange chromatography or affinity chromatography may offer more accessible options, though they may sacrifice some efficiency.

In conclusion, the extraction and purification of penicillin from mold cultures demand a blend of precision, patience, and problem-solving. By mastering filtration and chromatography techniques, researchers can isolate this life-saving antibiotic with high purity and yield, ensuring its efficacy in clinical applications. Whether in a state-of-the-art lab or a modest research setting, the principles remain the same: separate, isolate, and refine, turning mold into medicine.

Fungi's Survival Strategy: Understanding How Spores Ensure Species Continuity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Begin by collecting soil samples from environments likely to contain *Penicillium* species, such as gardens or decaying organic matter. Sterilize Petri dishes and prepare a nutrient agar medium (e.g., potato dextrose agar). Dilute the soil sample, spread it onto the agar, and incubate at 22–28°C for 5–7 days. Identify *Penicillium* colonies by their characteristic green or blue-green color and velvety texture.

Once a pure *Penicillium* culture is obtained, transfer it to a larger fermentation medium (e.g., corn steep liquor, lactose, and mineral salts) in a sterile flask or bioreactor. Incubate with agitation and aeration at 25–28°C for 7–14 days. After fermentation, filter the broth to remove mycelium, and then extract penicillin using solvent extraction or ion-exchange chromatography. Purify the extract through precipitation or crystallization.

Work in a sterile environment, such as a laminar flow hood, to prevent contamination. Wear personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, lab coats, and goggles, to avoid exposure to mold spores and chemicals. Ensure proper ventilation or use a biosafety cabinet when handling mold cultures. Sterilize all equipment and waste materials to prevent the spread of spores. Follow local regulations for disposal of biological materials.