Distinguishing between vegetative cells and spore mother cells is crucial in understanding the life cycles and reproductive strategies of various organisms, particularly in fungi and certain bacteria. Vegetative cells are primarily involved in growth, metabolism, and asexual reproduction, maintaining the organism's day-to-day functions. In contrast, spore mother cells are specialized cells that undergo meiosis or other forms of cell division to produce spores, which are resilient structures capable of surviving harsh conditions and dispersing to new environments. Key differences include their roles, cellular morphology, and genetic processes: vegetative cells are typically larger and actively dividing, while spore mother cells are often smaller, more compact, and genetically programmed for spore formation. Additionally, spore mother cells may exhibit distinct nuclear divisions or cellular modifications, such as thickening of cell walls, that are absent in vegetative cells. Understanding these distinctions is essential for studying organismal development, survival strategies, and biotechnological applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cell Type | Vegetative cells are the actively growing and dividing cells of a fungus, while spore mother cells are specialized cells that give rise to spores. |

| Function | Vegetative cells are involved in growth, metabolism, and asexual reproduction through fragmentation or budding. Spore mother cells are specifically dedicated to sexual or asexual spore production. |

| Location | Vegetative cells are found in the mycelium (network of fungal hyphae). Spore mother cells are typically located at the tips of specialized structures like sporangia, asci, or basidia. |

| Nuclear State | Vegetative cells are usually haploid (n) or dikaryotic (n+n) in fungi. Spore mother cells are often diploid (2n) before meiosis or dikaryotic (n+n) in basidiomycetes. |

| Division Type | Vegetative cells divide mitotically. Spore mother cells undergo meiosis (sexual spores) or mitosis (asexual spores) to produce spores. |

| Daughter Cells | Vegetative cells produce more vegetative cells. Spore mother cells produce spores, which are dormant, resistant structures capable of dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. |

| Morphology | Vegetative cells are typically elongated and thread-like (hyphal cells). Spore mother cells may be enlarged or differentiated in shape, often forming distinct structures like sporangia or asci. |

| Genetic Variation | Vegetative cells maintain the genetic identity of the parent. Spore mother cells, through meiosis, generate genetically diverse spores via recombination. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Vegetative cells represent the actively growing phase of the fungal life cycle. Spore mother cells are part of the reproductive phase, leading to spore formation. |

| Resistance | Vegetative cells are less resistant to environmental stresses. Spores produced by spore mother cells are highly resistant to desiccation, temperature extremes, and other adverse conditions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Nuclear Division Differences: Vegetative cells undergo mitosis; spore mother cells undergo meiosis for genetic diversity

- Cell Wall Changes: Spore mother cells develop thickened, protective walls; vegetative cells have standard walls

- Metabolic Shifts: Spore mother cells reduce metabolism; vegetative cells maintain active metabolic processes

- Genetic Content: Vegetative cells are diploid; spore mother cells are haploid post-meiosis

- Environmental Triggers: Spore formation is stress-induced; vegetative growth occurs in favorable conditions

Nuclear Division Differences: Vegetative cells undergo mitosis; spore mother cells undergo meiosis for genetic diversity

In the microscopic world of cellular division, the processes of mitosis and meiosis serve as distinct pathways, each with a unique purpose. Vegetative cells, the workhorses of growth and development, rely on mitosis to replicate their genetic material. This process ensures that each new cell receives an identical copy of the parent cell's DNA, maintaining the organism's genetic stability. Mitosis is a precise and efficient mechanism, ideal for the routine maintenance and expansion of tissues in multicellular organisms.

Contrastingly, spore mother cells embark on a different journey, one that prioritizes genetic diversity. Through meiosis, these cells undergo a specialized form of nuclear division, reducing the chromosome number by half and facilitating the exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes. This reduction division is a cornerstone of sexual reproduction, enabling the formation of spores or gametes with unique genetic combinations. The significance of this process becomes evident when considering the survival strategies of various organisms, particularly in challenging environments.

The distinction between these nuclear division processes is not merely academic; it has profound implications for the organisms' life cycles. Vegetative cells, with their mitotic division, contribute to the asexual reproduction and vegetative growth of organisms, ensuring the rapid proliferation of genetically identical individuals. This strategy is advantageous for colonizing stable environments, where adaptability is less critical. In contrast, spore mother cells, through meiosis, introduce genetic variation, a key factor in the long-term survival of species. This diversity equips offspring with a broader range of traits, increasing the chances of adaptation and survival in changing or unpredictable habitats.

Understanding these differences is crucial for various fields, from botany to mycology and beyond. For instance, in agriculture, recognizing the role of mitosis in vegetative growth can inform strategies for crop propagation and yield enhancement. Conversely, in the study of fungi, the meiotic division of spore mother cells explains the vast diversity of spore types and their dispersal mechanisms, which is essential for species identification and ecological research. By grasping these nuclear division differences, scientists can make more informed decisions, whether in breeding programs, conservation efforts, or the development of new biotechnological applications.

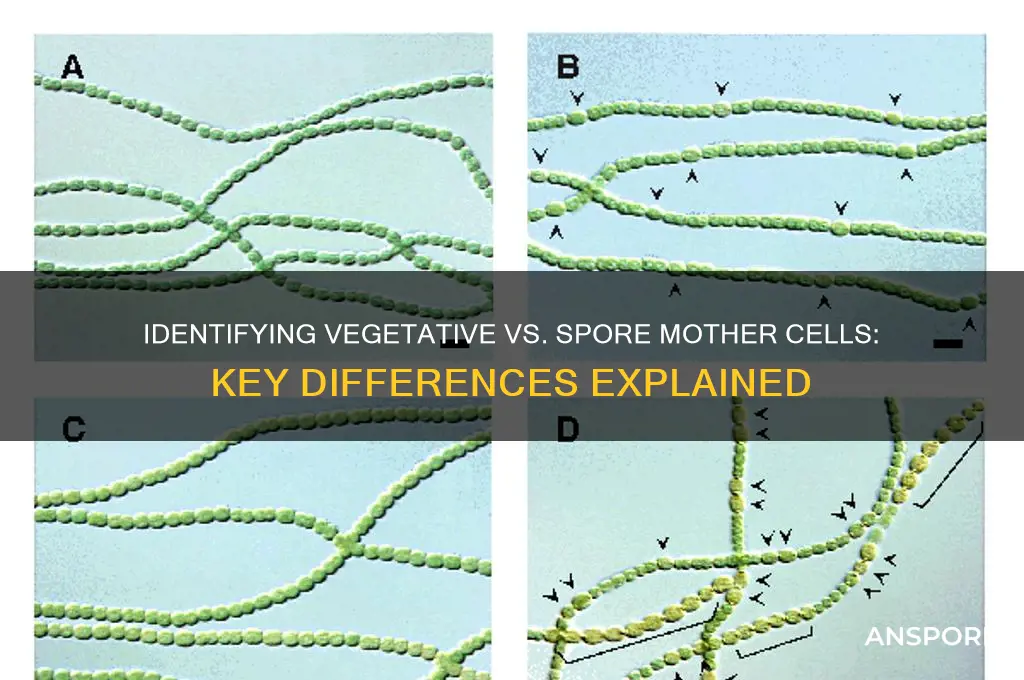

In practical terms, distinguishing between these cell types can be achieved through microscopic observation and genetic analysis. Vegetative cells typically exhibit a higher rate of division and are often found in actively growing tissues. Spore mother cells, on the other hand, may be identified by their unique morphology and the presence of specialized structures associated with spore formation. Advanced techniques, such as flow cytometry and DNA sequencing, can further confirm the ploidy levels and genetic diversity resulting from these distinct division processes. This knowledge empowers researchers and practitioners to manipulate and harness the potential of these cells for various applications, from food production to medical advancements.

Mastering Fungal Spore Collection: Techniques for Successful Harvesting

You may want to see also

Cell Wall Changes: Spore mother cells develop thickened, protective walls; vegetative cells have standard walls

One of the most striking differences between vegetative and spore mother cells lies in their cell wall composition and structure. While vegetative cells maintain a standard cell wall designed for everyday growth and metabolism, spore mother cells undergo a dramatic transformation, developing thickened, protective walls. This change is not merely cosmetic; it serves as a critical adaptation for survival under harsh conditions. The thickened wall acts as a barrier against desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other environmental stressors, ensuring the longevity of the spore.

To understand this distinction, consider the function of each cell type. Vegetative cells are the workhorses of an organism’s life cycle, focusing on nutrient absorption, growth, and reproduction under favorable conditions. Their cell walls are optimized for flexibility and permeability, allowing for efficient exchange of resources. In contrast, spore mother cells are specialized for survival, not growth. Their thickened walls are rich in sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer that provides durability and impermeability. This structural change is a clear marker for identifying spore mother cells under microscopic examination.

For researchers and practitioners, distinguishing between these cell types based on cell wall characteristics requires specific techniques. Staining methods, such as Calcofluor White, can highlight cell wall components, making the thickened walls of spore mother cells more visible under fluorescence microscopy. Additionally, electron microscopy can reveal the layered, dense structure of spore mother cell walls compared to the uniform, thin walls of vegetative cells. These tools are essential for accurate identification, particularly in species where morphological differences are subtle.

Practically, understanding cell wall changes has applications in fields like agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, in crop plants, identifying spore mother cells can help predict stress tolerance and improve breeding programs. In biotechnology, manipulating cell wall thickness could enhance the resilience of microorganisms used in industrial processes. By focusing on this specific cellular feature, scientists can unlock new strategies for improving organism survival and productivity in challenging environments.

In summary, the thickened, protective walls of spore mother cells stand in stark contrast to the standard walls of vegetative cells, offering a clear and functional distinction between these two cell types. This difference is not just a biological curiosity but a critical adaptation with practical implications. Whether in research, agriculture, or industry, recognizing and leveraging this cellular feature can lead to significant advancements in understanding and manipulating organismal resilience.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Acne Breakouts? Uncovering the Hidden Link

You may want to see also

Metabolic Shifts: Spore mother cells reduce metabolism; vegetative cells maintain active metabolic processes

In the intricate dance of cellular life, metabolic activity serves as a defining feature distinguishing spore mother cells from their vegetative counterparts. Spore mother cells, poised for dormancy, undergo a deliberate reduction in metabolic processes. This shift is not merely a slowdown but a strategic recalibration, minimizing energy expenditure to conserve resources for long-term survival. In contrast, vegetative cells remain metabolic powerhouses, sustaining active processes essential for growth, division, and immediate environmental interaction. This divergence in metabolic behavior is a critical marker for differentiation, offering insights into the distinct roles these cells play in the life cycle of organisms.

Consider the practical implications of this metabolic shift. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism for spore formation, spore mother cells decrease ATP production by up to 70% compared to vegetative cells. This reduction is achieved through downregulation of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, pathways central to energy generation. Researchers can quantify this difference using techniques like fluorometric ATP assays or metabolic flux analysis, providing a tangible metric for distinguishing cell types. Understanding this metabolic slowdown is not just academic—it has applications in biotechnology, where controlling spore formation is crucial for preserving microbial cultures or producing bioactive compounds.

From an instructive standpoint, identifying metabolic shifts requires targeted experimental approaches. One effective method is measuring enzyme activity levels of key metabolic enzymes, such as pyruvate kinase or citrate synthase. Vegetative cells exhibit higher activity in these enzymes, reflecting their need for continuous energy production. Conversely, spore mother cells show significantly reduced activity, aligning with their energy-conserving state. Pairing these measurements with transcriptomic analysis can reveal downregulation of genes encoding metabolic enzymes, offering a molecular basis for the observed metabolic differences. For laboratories, this dual approach provides a robust framework for distinguishing cell types with precision.

Persuasively, the metabolic distinction between these cells underscores their evolutionary adaptation to environmental challenges. Vegetative cells, with their high metabolic activity, thrive in nutrient-rich conditions, optimizing growth and reproduction. Spore mother cells, however, prepare for adversity by minimizing metabolic demands, a strategy that ensures survival in harsh environments. This dichotomy highlights the elegance of biological systems, where metabolic flexibility is tailored to specific life stages. For educators, framing this metabolic shift as a survival mechanism can engage students in the broader principles of cellular adaptation and resilience.

In conclusion, the metabolic divergence between spore mother cells and vegetative cells is a nuanced yet accessible criterion for differentiation. By focusing on energy production pathways, enzyme activity, and molecular markers, researchers and practitioners can accurately distinguish these cell types. This knowledge not only advances fundamental biology but also informs practical applications in biotechnology and education, demonstrating the profound impact of metabolic shifts in shaping cellular destiny.

Mastering Spore: Befriending Epic Creatures with Proven Strategies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic Content: Vegetative cells are diploid; spore mother cells are haploid post-meiosis

In the realm of cellular biology, understanding the genetic makeup of cells is crucial for distinguishing between vegetative and spore mother cells. One key differentiator lies in their ploidy levels: vegetative cells are diploid, containing two sets of chromosomes, while spore mother cells are haploid, possessing only one set of chromosomes post-meiosis. This fundamental difference has significant implications for their function, behavior, and role in the life cycle of organisms.

Consider the process of meiosis, where a diploid cell undergoes two rounds of cell division to produce four haploid cells. In the context of spore mother cells, this process is essential for generating spores capable of developing into new individuals. For instance, in fungi, the spore mother cell undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, which can then germinate and grow into new fungal organisms. In contrast, vegetative cells remain diploid, allowing them to carry out essential metabolic functions, such as nutrient absorption and growth, without the need for genetic recombination.

To illustrate the practical implications of this genetic distinction, let's examine the life cycle of a fern. The sporophyte generation (diploid) produces spore mother cells through meiosis, which give rise to haploid spores. These spores develop into the gametophyte generation, where vegetative cells (still haploid) grow and eventually produce gametes. Fertilization restores the diploid state, and the cycle repeats. This example highlights the critical role of ploidy in regulating cellular function and development.

When attempting to distinguish between vegetative and spore mother cells in a laboratory setting, several techniques can be employed. One common method is flow cytometry, which measures the DNA content of cells to determine their ploidy level. By staining cells with a DNA-binding dye, such as propidium iodide, researchers can quantify the amount of DNA present in each cell. Diploid vegetative cells will exhibit twice the DNA content of haploid spore mother cells, providing a clear distinction between the two. Additionally, techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) can be used to visualize specific chromosomes, further confirming the ploidy status of the cells.

In conclusion, the genetic content of vegetative and spore mother cells serves as a critical distinguishing factor, with diploid vegetative cells and haploid spore mother cells playing distinct roles in the life cycle of organisms. By understanding the underlying genetic differences and employing appropriate analytical techniques, researchers can accurately identify and study these cell types, shedding light on the complex mechanisms governing cellular function, development, and reproduction. This knowledge has far-reaching implications, from advancing our understanding of fundamental biology to informing practical applications in fields like agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology.

Effective Ways to Remove Mold Spores from Your Carpet

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Spore formation is stress-induced; vegetative growth occurs in favorable conditions

Spore formation and vegetative growth represent two distinct survival strategies in microorganisms, each triggered by specific environmental conditions. While vegetative cells thrive in nutrient-rich, stable environments, spore mother cells emerge as a response to stress, such as nutrient depletion, desiccation, or extreme temperatures. This dichotomy highlights how organisms adapt to their surroundings, prioritizing growth in favorable conditions and survival in adversity. Understanding these triggers not only sheds light on microbial behavior but also has practical applications in fields like food preservation, medicine, and biotechnology.

Consider the lifecycle of *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied bacterium. In nutrient-rich media, vegetative cells proliferate rapidly, focusing on metabolism and replication. However, when starved of essential nutrients like carbon or nitrogen, the cell initiates a stress response, activating genes that lead to spore formation. For instance, the addition of less than 0.05% glucose to a culture medium can trigger this transition in *B. subtilis*, demonstrating how subtle environmental changes can induce a dramatic shift in cellular function. This example underscores the precision with which microorganisms detect and respond to stress.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing these environmental triggers can inform strategies for controlling microbial growth. In food preservation, for example, creating conditions that favor vegetative growth (e.g., maintaining optimal pH and moisture levels) can inadvertently accelerate spoilage. Conversely, applying stressors like heat or dehydration can force spore formation, which, while dormant, may pose risks if conditions later become favorable for germination. For instance, pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds effectively kills vegetative cells but may leave spores intact, necessitating additional measures like sterilization for complete safety.

Comparatively, the distinction between vegetative and spore mother cells also illuminates broader evolutionary principles. Vegetative growth maximizes resource utilization during times of plenty, ensuring rapid proliferation and colonization. Spore formation, on the other hand, is a long-term survival mechanism, allowing organisms to endure harsh conditions for years or even decades. This duality mirrors the balance between exploitation and conservation seen across biological systems, from hibernation in mammals to seed dormancy in plants. By studying these microbial strategies, we gain insights into resilience and adaptability in the natural world.

In conclusion, environmental triggers act as the linchpin distinguishing vegetative growth from spore formation. Favorable conditions promote metabolic activity and replication, while stress induces a protective, dormant state. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of microbial biology but also equips us with tools to manipulate these processes for practical ends. Whether in the lab, the kitchen, or the clinic, recognizing these triggers allows us to harness or counteract microbial behavior, shaping outcomes in ways that benefit human health and industry.

Turning Foes into Friends: Befriending Hostile Tribes in Spore

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Vegetative cells are typically smaller, uniform in size, and actively involved in growth and metabolism. Spore mother cells, however, are larger, often swollen, and undergo differentiation to form spores, showing distinct changes in shape and size during sporulation.

Vegetative cells contain a single copy of the genome and divide by binary fission. Spore mother cells, in contrast, often undergo DNA replication and rearrangement to prepare for spore formation, sometimes containing multiple copies of the genome or specialized genetic material.

Vegetative cells are responsible for growth, metabolism, and reproduction under favorable conditions. Spore mother cells are specialized for survival under stress, producing spores that are dormant and resistant to harsh environments.

Vegetative cells can transform into spore mother cells under specific environmental triggers, such as nutrient depletion or stress. This transformation is regulated by genetic and signaling pathways, initiating the sporulation process.