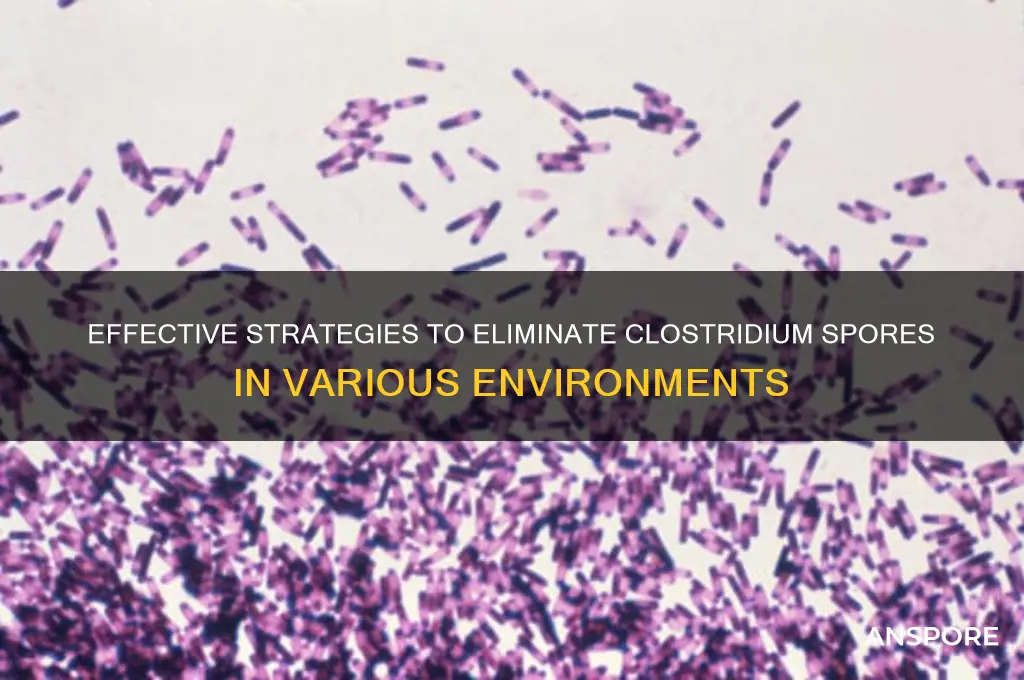

Eliminating *Clostridium* spores, particularly those of *Clostridioides difficile* (formerly *Clostridium difficile*), is a critical challenge due to their remarkable resistance to standard disinfection methods. These spores can survive harsh environmental conditions, including heat, desiccation, and many common disinfectants, making them persistent in healthcare settings and contributing to healthcare-associated infections. Effective elimination strategies include the use of sporicidal agents such as chlorine-based disinfectants (e.g., sodium hypochlorite), hydrogen peroxide, or peracetic acid, which can penetrate and disrupt the spore's protective coat. Additionally, physical methods like steam sterilization (autoclaving) at high temperatures and pressures are highly effective in destroying spores. Proper environmental cleaning protocols, combined with appropriate disinfectant selection and contact time, are essential to reduce the risk of *Clostridium* spore transmission and prevent outbreaks.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heat Resistance | Spores survive boiling (100°C) for up to 5 minutes. Autoclaving at 121°C for 15-30 minutes is required for complete elimination. |

| Chemical Disinfectants | Spores are resistant to most disinfectants. Effective agents include: |

| - Chlorine dioxide (200-1000 ppm for 30-60 minutes) | |

| - Hydrogen peroxide (6-7% for 30 minutes) | |

| - Peracetic acid (0.2-0.35% for 30-60 minutes) | |

| pH Sensitivity | Spores are most resistant at neutral pH (7). Slightly acidic or alkaline conditions may reduce resistance. |

| Radiation Resistance | Spores are highly resistant to UV light. Gamma irradiation (2-10 kGy) is effective. |

| Physical Methods | Filtration (0.22 μm filters) can remove spores but not eliminate them. |

| Environmental Survival | Spores can survive in soil for years and are resistant to desiccation. |

| Biological Control | No known biological agents (e.g., bacteriophages) effectively target spores. |

| Temperature for Elimination | Minimum 121°C under pressure (autoclave) for 15-30 minutes. |

| Chemical Concentration | Higher concentrations of disinfectants (e.g., 10% hydrogen peroxide) are needed for efficacy. |

| Time Required | Prolonged exposure (30-60 minutes) to chemicals is necessary for spore elimination. |

| Resistance to Antibiotics | Spores are not affected by antibiotics; only the vegetative form is susceptible. |

| Surface Decontamination | Surfaces must be cleaned before disinfection to ensure chemical contact with spores. |

| Storage Conditions | Spores remain viable in dry, cool conditions for extended periods. |

| Industrial Applications | Used in food processing (e.g., retorting at 121°C) and medical sterilization. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Heat Sterilization Techniques: Autoclaving at 121°C for 15-30 minutes effectively kills Clostridium spores

- Chemical Disinfectants: Use sporicides like bleach, hydrogen peroxide, or peracetic acid for surface disinfection

- Filtration Methods: Sterilizing-grade filters (0.22 μm) remove spores from liquids and gases

- Radiation Treatment: Gamma or electron beam irradiation destroys spores in food and medical supplies

- pH and Pressure Control: Extreme pH levels or high hydrostatic pressure can inactivate Clostridium spores

Heat Sterilization Techniques: Autoclaving at 121°C for 15-30 minutes effectively kills Clostridium spores

Clostridium spores are notoriously resilient, capable of surviving extreme conditions that would destroy most other microorganisms. Among the most reliable methods to eliminate them is heat sterilization, specifically autoclaving at 121°C for 15 to 30 minutes. This technique leverages the principle of moist heat, which penetrates materials more effectively than dry heat, ensuring thorough sterilization. The high temperature and pressure combination denatures the spore’s proteins and disrupts its cellular structures, rendering it non-viable. This method is widely used in laboratories, medical facilities, and food processing industries due to its consistency and reliability.

To implement autoclaving effectively, follow these steps: first, ensure the materials to be sterilized are placed in heat-resistant containers or autoclave bags. Load the autoclave chamber, leaving enough space for steam circulation. Set the machine to 121°C and allow it to run for at least 15 minutes, extending to 30 minutes for denser or larger volumes. After the cycle, allow the autoclave to cool naturally to avoid contamination. Proper maintenance of the autoclave, including regular calibration and cleaning, is crucial to ensure consistent performance. This process is particularly critical when handling Clostridium spores, as incomplete sterilization can lead to their survival and potential regrowth.

While autoclaving is highly effective, it’s not without limitations. Materials sensitive to heat or moisture, such as certain plastics or electronic components, may be damaged. In such cases, alternative methods like chemical sterilization or radiation must be considered. However, for most applications involving Clostridium spores, autoclaving remains the gold standard. Its simplicity, combined with its proven efficacy, makes it an indispensable tool in environments where spore elimination is non-negotiable.

A comparative analysis highlights why autoclaving stands out among sterilization methods. Unlike chemical disinfectants, which may not penetrate spores effectively, autoclaving guarantees complete eradication. Compared to dry heat sterilization, which requires higher temperatures and longer exposure times, autoclaving is more efficient and less energy-intensive. Its ability to handle large volumes of materials simultaneously further enhances its practicality. For industries and laboratories dealing with Clostridium spores, investing in a reliable autoclave system is a strategic decision that ensures safety and compliance.

In conclusion, autoclaving at 121°C for 15 to 30 minutes is a scientifically validated and practical approach to eliminating Clostridium spores. Its effectiveness, combined with its ease of use, makes it the preferred choice for professionals across various fields. By adhering to proper procedures and maintaining equipment, users can confidently rely on this method to achieve sterilization goals. Whether in a clinical setting, research lab, or industrial facility, autoclaving remains a cornerstone technique in the fight against spore-forming pathogens.

Buying Psychedelic Spores in Ireland: Legalities and Availability Explained

You may want to see also

Chemical Disinfectants: Use sporicides like bleach, hydrogen peroxide, or peracetic acid for surface disinfection

Clostridium spores are notoriously resilient, surviving extreme conditions that would destroy most other microorganisms. To effectively eliminate them, chemical disinfectants known as sporicides are essential. Among these, bleach, hydrogen peroxide, and peracetic acid stand out for their proven efficacy against Clostridium spores. Each of these agents works by disrupting the spore’s protective coat and neutralizing its core, ensuring thorough disinfection. However, their application requires precision to maximize effectiveness while minimizing risks to users and surfaces.

Bleach, a household staple, is a cost-effective sporicide when used correctly. A solution of 5,000–10,000 ppm (parts per million) of sodium hypochlorite, equivalent to 1:10 to 1:50 dilution of household bleach, is recommended for surface disinfection. Allow the solution to remain in contact with the surface for at least 10 minutes to ensure spore inactivation. Caution is advised, as bleach can corrode metals and discolor fabrics. Always wear gloves and ensure proper ventilation to avoid respiratory irritation. For healthcare settings, follow CDC guidelines for precise dilution ratios and contact times.

Hydrogen peroxide, particularly in its stabilized or vaporized forms, offers a more environmentally friendly alternative. Concentrations of 6–7% hydrogen peroxide are effective against Clostridium spores when applied for 5–10 minutes. Its decomposing nature into water and oxygen makes it safer for use on sensitive surfaces and in food processing areas. However, it is less stable than bleach and requires storage away from light and heat. For larger areas, hydrogen peroxide vapor systems provide thorough disinfection but necessitate professional handling due to their complexity.

Peracetic acid, a potent oxidizer, is highly effective even at low concentrations (0.2–0.35%). It is commonly used in the food and beverage industry for its rapid action and broad-spectrum efficacy. Unlike bleach, it leaves no harmful residues, making it ideal for surfaces that come into contact with consumables. However, its strong odor and potential skin irritation require protective measures, including gloves and eye protection. Always follow manufacturer instructions for dilution and application to avoid surface damage or user harm.

In selecting a sporicide, consider the specific environment and surface material. Bleach is versatile but harsh, hydrogen peroxide is gentle but less stable, and peracetic acid is powerful but requires careful handling. Each has its place in the fight against Clostridium spores, and their proper use ensures not only disinfection but also safety and practicality. Regular training and adherence to guidelines are critical to achieving consistent results in both industrial and domestic settings.

Micrococcus luteus: Understanding Its Spore Formation Capabilities Explained

You may want to see also

Filtration Methods: Sterilizing-grade filters (0.22 μm) remove spores from liquids and gases

Sterilizing-grade filters with a pore size of 0.22 μm are a cornerstone in the battle against Clostridium spores in liquids and gases. These filters operate on a simple yet powerful principle: physical exclusion. The spores, typically ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 μm in diameter, are mechanically trapped by the filter’s matrix, preventing their passage. This method is particularly effective in industries like pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and food and beverage, where spore contamination can have catastrophic consequences. Unlike chemical or thermal methods, filtration is a non-destructive process, preserving the integrity of heat-sensitive or chemically reactive materials.

Implementing sterilizing-grade filters requires careful consideration of the filtration system’s design and operation. For liquids, the filter must be compatible with the fluid’s viscosity, pH, and chemical composition to avoid clogging or degradation. Pre-filters are often used to remove larger particles, extending the life of the sterilizing-grade filter. In gas filtration, the system must account for flow rate and pressure differentials to ensure efficient spore removal without compromising performance. Regular integrity testing, such as bubble point or diffusion tests, is essential to confirm the filter’s effectiveness. Manufacturers like Merck and Pall offer validated filters with certifications for spore retention, providing reliability in critical applications.

One of the key advantages of 0.22 μm filters is their ability to achieve sterility without altering the product’s properties. For example, in biopharmaceutical production, these filters are used to sterilize culture media, buffers, and final drug products. Similarly, in the beverage industry, they ensure the removal of spores from water and other ingredients, preventing spoilage and ensuring safety. However, it’s crucial to note that filtration alone may not be sufficient for all scenarios. Spores can aggregate or form biofilms, potentially bypassing the filter. Thus, combining filtration with other methods, such as heat treatment or chemical disinfection, can enhance overall efficacy.

Despite their effectiveness, sterilizing-grade filters are not without limitations. They are not suitable for removing dissolved contaminants or toxins produced by spores, such as botulinum neurotoxin. Additionally, the cost and scalability of filtration systems can be prohibitive for small-scale operations. Proper training and adherence to protocols are essential to avoid human error, such as incorrect installation or failure to monitor filter integrity. When used correctly, however, 0.22 μm filters provide a reliable, reproducible method for spore removal, making them an indispensable tool in industries where sterility is non-negotiable.

In conclusion, sterilizing-grade filters (0.22 μm) offer a precise and non-invasive solution for eliminating Clostridium spores from liquids and gases. Their mechanical action ensures spore retention without compromising product quality, making them ideal for sensitive applications. While they require careful implementation and may need to be paired with complementary methods, their reliability and versatility cement their role as a critical component in spore control strategies. Whether in large-scale manufacturing or laboratory settings, these filters provide a robust defense against spore-related risks.

Mastering Spore Prints: A Step-by-Step Guide Using Spore Syringes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Radiation Treatment: Gamma or electron beam irradiation destroys spores in food and medical supplies

Clostridium spores, notorious for their resilience, pose significant challenges in food safety and medical sterilization. Among the methods to eliminate them, radiation treatment stands out for its efficacy and precision. Gamma and electron beam irradiation, in particular, offer a non-chemical approach to destroy these spores, ensuring safety without altering the essential properties of the treated materials. This method is widely recognized by regulatory bodies, including the FDA, for its ability to reduce microbial contamination in food and medical supplies.

Mechanism and Application

Gamma irradiation employs cobalt-60 as its source, emitting high-energy photons that penetrate materials deeply, disrupting the DNA of Clostridium spores and rendering them incapable of reproduction. Electron beam irradiation, on the other hand, uses accelerated electrons, which are less penetrating but highly effective for surface or shallow treatments. For food, doses typically range from 1 to 10 kGy, depending on the product and desired log reduction. Medical supplies, such as surgical instruments or bandages, may require higher doses, often exceeding 25 kGy, to ensure complete sterilization. Both methods are applied in specialized facilities under strict safety protocols to prevent exposure to operators.

Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Compared to chemical treatments or heat sterilization, radiation offers distinct advantages. It does not introduce residues, making it ideal for sensitive products like spices, fruits, and medical devices. Unlike heat, it preserves the nutritional value and sensory qualities of food, as it operates at low temperatures. Additionally, its ability to treat bulk materials uniformly reduces processing time and costs. For instance, irradiation has been successfully used to eliminate *Clostridium botulinum* spores in spices, preventing foodborne outbreaks without compromising flavor.

Practical Considerations and Limitations

While effective, radiation treatment is not without limitations. High initial setup costs and the need for specialized equipment make it less accessible for small-scale operations. Certain materials, such as plastics or packaging, may degrade under high doses, requiring careful selection of compatible materials. Furthermore, public perception remains a challenge, as irradiated food often faces skepticism despite its safety and approval by health authorities. Clear labeling and education are essential to address these concerns.

Implementation Tips

For optimal results, follow these guidelines: (1) Determine the appropriate dose based on the product and spore load—consult regulatory guidelines or experts for accuracy. (2) Ensure uniform exposure by proper packaging and arrangement of items. (3) Monitor the process using dosimeters to verify effectiveness. (4) Store irradiated products appropriately to maintain sterility. When applied correctly, radiation treatment provides a reliable, scalable solution to eliminate Clostridium spores, safeguarding both food and medical supplies.

Giant Puffball's Astonishing Spore Count: Unveiling Nature's Tiny Secrets

You may want to see also

pH and Pressure Control: Extreme pH levels or high hydrostatic pressure can inactivate Clostridium spores

Extreme pH levels can disrupt the delicate balance Clostridium spores rely on for survival. These spores, notorious for their resilience, thrive in neutral to slightly alkaline environments (pH 7-8). However, exposing them to highly acidic (pH < 3) or highly alkaline (pH > 11) conditions can denature their proteins and damage their DNA, rendering them inactive. For instance, a study published in the *Journal of Food Protection* demonstrated that immersing Clostridium spores in a solution with a pH of 2.5 for 30 minutes reduced their viability by over 99.9%. This method is particularly effective in food processing, where acidic ingredients like vinegar or citric acid can be incorporated to create an inhospitable environment for these spores.

High hydrostatic pressure (HHP) offers another powerful tool to combat Clostridium spores. By subjecting spores to pressures exceeding 400 MPa (approximately 4,000 times atmospheric pressure) for several minutes, their cellular structures are compromised. This process, known as pascalization, disrupts the spore’s core and inactivates its metabolic functions. For example, research in *Applied and Environmental Microbiology* showed that applying 600 MPa for 10 minutes inactivated 99.999% of Clostridium botulinum spores. HHP is widely used in the food industry to sterilize products like juices and ready-to-eat meals without compromising their nutritional value or sensory qualities, making it a preferred alternative to thermal processing.

While both pH control and HHP are effective, their application requires careful consideration. Extreme pH treatments must be compatible with the product being treated, as some materials may degrade or alter in taste under such conditions. For instance, acidic treatments are unsuitable for dairy products, as they can curdle milk proteins. Similarly, HHP equipment is costly and requires specialized facilities, limiting its accessibility for small-scale operations. However, when applied correctly, these methods provide a non-thermal, chemical-free approach to spore inactivation, aligning with consumer demand for minimally processed, preservative-free foods.

In practice, combining pH and pressure treatments can enhance their effectiveness. A two-step process—first lowering the pH to weaken the spores, followed by HHP to deliver the final blow—can achieve complete inactivation with shorter treatment times. For example, treating Clostridium spores at pH 4.5 followed by 400 MPa for 5 minutes has been shown to be more efficient than either method alone. This synergistic approach maximizes spore elimination while minimizing the impact on product quality, making it a valuable strategy for industries ranging from food preservation to medical sterilization.

Ultimately, pH and pressure control offer precise, science-backed solutions for eliminating Clostridium spores. Whether applied individually or in combination, these methods leverage the spores’ vulnerabilities to extreme conditions, providing effective alternatives to traditional heat or chemical treatments. By understanding the specific requirements and limitations of each technique, industries can tailor their approaches to ensure safety without sacrificing product integrity. This makes pH and pressure control indispensable tools in the ongoing battle against Clostridium contamination.

Promote Creatures to Tribal in Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The most effective methods include autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for 30 minutes, using chemical disinfectants like chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm) or hydrogen peroxide, and exposure to high temperatures (e.g., incineration).

Yes, Clostridium spores are highly resistant to standard disinfection processes, including many common disinfectants and low-temperature sterilization methods. Specialized treatments are required for effective elimination.

Clostridium spores can remain viable in the environment for years, even decades, under favorable conditions, making them challenging to eradicate without proper intervention.

Natural methods are generally ineffective against Clostridium spores due to their resilience. Chemical or heat-based treatments are necessary for reliable elimination.