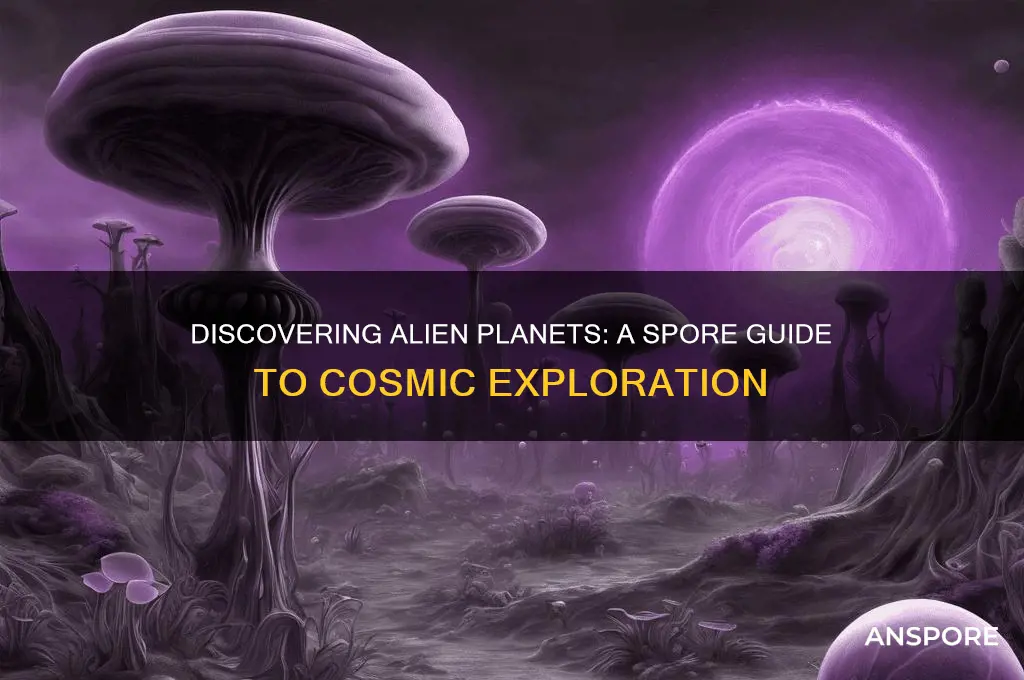

Finding alien planets, particularly those that might resemble the diverse and imaginative worlds of *Spore*, involves a blend of cutting-edge astronomy and creative speculation. Scientists use advanced telescopes like Kepler and TESS to detect exoplanets by observing subtle changes in a star's brightness caused by orbiting planets. Techniques such as radial velocity measurements and direct imaging further refine these discoveries. While *Spore* allows players to design fantastical ecosystems and creatures, real-world exoplanet research focuses on identifying habitable zones, atmospheric compositions, and potential biosignatures. Combining scientific methods with the imaginative spirit of *Spore* inspires both the exploration of actual alien worlds and the creation of virtual ones, bridging the gap between reality and fantasy in the search for life beyond Earth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Game | Spore |

| Objective | Find alien planets and explore extraterrestrial life |

| Method to Find Alien Planets | Use the Space Stage in Spore to travel between star systems |

| Tools Required | Spaceship with upgraded engines, fuel, and scanning capabilities |

| Planet Types | T-0 (uninhabitable), T-1 (microbial life), T-2 (tribal life), T-3 (civilized life) |

| Scanning | Use the planet scanner to detect life forms and resources |

| Colonization | Establish colonies on T-2 and T-3 planets to expand your empire |

| Alien Encounters | Interact with or combat alien species depending on their disposition |

| Resources | Collect spices, gems, and rare items from alien planets |

| Achievements | Unlock achievements for discovering and colonizing multiple planets |

| Difficulty | Varies based on the planet type and alien presence |

| Tips | Upgrade your spaceship, explore thoroughly, and avoid hostile aliens |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Transit Method: Detect dimming starlight as planets pass, indicating potential alien worlds orbiting distant stars

- Radial Velocity: Measure star wobbles caused by planetary gravity, revealing hidden exoplanets

- Direct Imaging: Capture photos of planets using advanced telescopes and light-blocking techniques

- Microlensing: Observe gravitational lensing events to find planets around faraway stars

- Astrometry: Track star movements precisely to infer orbiting planets' presence indirectly

Transit Method: Detect dimming starlight as planets pass, indicating potential alien worlds orbiting distant stars

The transit method is a powerful tool in the search for alien planets, relying on a simple yet elegant principle: as a planet passes in front of its star, it blocks a tiny fraction of the star's light, causing a measurable dip in brightness. This dimming, often less than 1%, is a telltale sign of a potential exoplanet. For example, NASA's Kepler mission used this method to detect thousands of exoplanet candidates by monitoring the brightness of over 150,000 stars simultaneously. The key lies in precision—instruments like the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) can detect changes in brightness as small as 0.0001%, making it possible to identify even Earth-sized planets around distant stars.

To apply the transit method effectively, astronomers follow a series of steps. First, they select a target star and monitor its brightness over time using highly sensitive telescopes. Next, they analyze the light curve—a graph of the star's brightness versus time—for periodic dips. If these dips repeat at regular intervals, it suggests a planet is orbiting the star and passing in front of it at consistent intervals. Caution must be taken to rule out false positives, such as binary star systems or instrumental errors. Advanced techniques, like measuring the star's radial velocity, can confirm whether the dimming is indeed caused by a planet. Practical tip: amateur astronomers can contribute to this effort by joining citizen science projects like Planet Hunters, where they analyze real Kepler data to identify potential transits.

One of the most compelling aspects of the transit method is its ability to reveal not just the presence of a planet, but also its size and orbit. By measuring the depth of the dimming, astronomers can calculate the planet’s radius relative to its star. For instance, if a star dims by 0.01% during a transit, it suggests a planet with a radius about 10% that of the star. Additionally, the duration and frequency of the transits provide insights into the planet’s orbital period and distance from its star. Comparative analysis shows that this method is particularly effective for detecting close-in planets, such as hot Jupiters, which orbit their stars in just a few days. However, it can also identify Earth-like planets in the habitable zone with sufficient observation time and precision.

Despite its strengths, the transit method has limitations that must be considered. It is most effective for edge-on planetary systems, where the planet’s orbit aligns with our line of sight. If the orbit is tilted, the planet may not pass in front of the star from our perspective, making detection impossible. Furthermore, small or distant planets produce faint signals that can be drowned out by stellar activity or instrumental noise. To mitigate these challenges, astronomers often combine transit data with other techniques, such as the radial velocity method, to confirm detections and gather more detailed information about the planet’s mass and composition. Takeaway: while the transit method is a cornerstone of exoplanet discovery, it is most powerful when used in conjunction with complementary approaches.

In the context of "how to find alien planets spore," the transit method serves as a foundational technique for identifying potential habitats beyond our solar system. By detecting the subtle dimming of starlight, astronomers can pinpoint planets that might harbor life, especially those within the habitable zone where liquid water could exist. For enthusiasts and aspiring astronomers, understanding this method provides a tangible way to engage with the search for extraterrestrial life. Practical tip: use online tools like the NASA Exoplanet Archive to explore confirmed exoplanets discovered via the transit method and visualize their characteristics. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding but also inspires further exploration of the cosmos.

Apple Cider Vinegar: Effective Remedy to Kill Ringworm Spores?

You may want to see also

Radial Velocity: Measure star wobbles caused by planetary gravity, revealing hidden exoplanets

Stars, like our Sun, are not always solitary travelers in the vastness of space. The gravitational pull of orbiting planets can cause a star to wobble ever so slightly, a phenomenon known as radial velocity. This subtle dance is a telltale sign of hidden exoplanets, and astronomers have honed techniques to detect these celestial waltzes. By analyzing the spectrum of a star's light, scientists can measure shifts in its wavelength, indicating the star's movement toward or away from Earth. These periodic shifts correspond to the gravitational tug of an unseen planet, allowing researchers to infer the presence, mass, and orbit of exoplanets without ever directly observing them.

To employ the radial velocity method effectively, astronomers use high-precision spectrographs, such as the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS), which can detect velocity changes as small as 1 meter per second. This sensitivity is crucial, as the wobble caused by Earth-sized planets is minuscule compared to that of gas giants. For instance, a Jupiter-sized planet might cause its star to wobble at speeds of 10–100 meters per second, while an Earth-like planet would induce a wobble of just 0.1 meters per second. By collecting data over months or years, astronomers can identify recurring patterns in the star's motion, revealing the orbital period and minimum mass of the exoplanet.

One of the key advantages of the radial velocity method is its ability to detect planets in a wide range of orbits, from tight, Mercury-like paths to more distant, Jupiter-like trajectories. However, it is not without limitations. The method is most effective for detecting large planets close to their stars, as these produce the strongest signals. Additionally, radial velocity alone cannot determine a planet's size or composition—only its mass relative to the star. To overcome these constraints, astronomers often combine radial velocity data with other techniques, such as transit photometry, to paint a more complete picture of an exoplanet's characteristics.

For aspiring exoplanet hunters, understanding the radial velocity method is a critical step in the search for alien worlds. Amateur astronomers can contribute to this field by monitoring nearby stars for signs of wobble, using affordable spectrographs or collaborating with professional observatories. Online platforms like the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) provide resources and tutorials for those interested in learning the basics of spectroscopy and data analysis. By participating in citizen science projects, enthusiasts can help expand our catalog of exoplanets and potentially discover new worlds beyond our solar system.

In the broader context of *Spore*-like exploration, the radial velocity method serves as a metaphor for uncovering hidden potential. Just as players in *Spore* evolve and adapt to discover new species and worlds, astronomers use this technique to reveal the unseen diversity of planetary systems. The method’s reliance on precision and patience mirrors the game’s progression, where small, incremental changes lead to significant discoveries. Whether in a virtual universe or the real cosmos, the pursuit of knowledge begins with observing the subtle clues that point to something extraordinary.

Unveiling the Microscopic World: Bacillus Spore Size Explained

You may want to see also

Direct Imaging: Capture photos of planets using advanced telescopes and light-blocking techniques

Direct imaging stands as one of the most visually compelling methods for detecting exoplanets, offering a glimpse of distant worlds in a way that feels almost tangible. Unlike indirect methods that infer a planet’s presence through its effects on a star, direct imaging captures the planet itself, albeit as a faint speck of light against the overwhelming brightness of its host star. This technique relies on advanced telescopes equipped with coronagraphs or starshades, which block the star’s blinding light, allowing the dimmer planet to become visible. While challenging, direct imaging provides invaluable data, including atmospheric composition and orbital characteristics, making it a cornerstone of exoplanet exploration.

To achieve direct imaging, astronomers employ a series of precise steps. First, they select a target star system, often young or distant, where planets are more likely to be separated enough from their star to be distinguishable. Next, they use adaptive optics to correct for atmospheric distortion, ensuring the sharpest possible images. Coronagraphs, which act like tiny masks within the telescope, block the star’s light, while starshades—large, flower-shaped structures positioned in front of the telescope—can be used in space-based missions to achieve the same effect. Finally, advanced image processing techniques isolate the planet’s light, revealing its presence and properties. This method is particularly effective for large, Jupiter-sized planets orbiting far from their stars, as they emit more infrared radiation and are easier to distinguish.

Despite its potential, direct imaging is not without limitations. The technique is currently constrained by the vast distance between Earth and exoplanets, as well as the overwhelming brightness of stars compared to their planets. For example, a star can be 10 billion times brighter than its orbiting planet, making detection akin to spotting a firefly next to a searchlight from miles away. Additionally, direct imaging is most successful for planets in wide orbits, which take decades or even centuries to complete, limiting the number of systems that can be studied in detail. However, ongoing advancements in telescope technology, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, are pushing these boundaries, enabling the detection of smaller, Earth-like planets in the future.

The payoff for overcoming these challenges is immense. Direct imaging not only confirms the existence of exoplanets but also provides spectral data that can reveal their atmospheric composition, temperature, and even weather patterns. This information is crucial for assessing habitability and understanding the diversity of planetary systems in our galaxy. For instance, the first directly imaged exoplanet, HR 8799 b, has been studied extensively, revealing a complex atmosphere rich in methane and water vapor. Such discoveries inspire further exploration and underscore the importance of direct imaging in the search for life beyond Earth.

In practice, direct imaging is a testament to human ingenuity and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. It requires collaboration across disciplines, from engineering to astrophysics, and pushes the limits of current technology. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, understanding this method offers a deeper appreciation for the challenges and triumphs of exoplanet discovery. While direct imaging may not yet be the most common technique, its potential to reveal alien worlds in stunning detail ensures its place as a vital tool in the quest to find life among the stars.

Collimating Spores: Visualizing Their Unique Transformation Under Microscopy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Microlensing: Observe gravitational lensing events to find planets around faraway stars

Gravitational microlensing is a cosmic magnifying glass, bending light from distant stars to reveal hidden planets. When a star passes in front of another, more distant star, its gravity acts as a lens, amplifying the background star's light. This brief, telltale brightening can signal the presence of planets orbiting the foreground star, even if they’re too faint to see directly. Unlike other planet-finding methods, microlensing excels at detecting low-mass planets in wide orbits, akin to Earth’s position in our solar system, making it a unique tool in the search for alien worlds.

To harness microlensing for planet discovery, astronomers monitor dense star fields, such as those toward the center of the Milky Way. Specialized telescopes and surveys, like the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) and the Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA), scan these regions nightly, searching for the characteristic light curves of microlensing events. When a planet orbits the lensing star, it creates a distinct anomaly in the brightening pattern, a brief deviation lasting hours to days. Analyzing these anomalies requires precision and speed, as the events are transient and cannot be repeated.

One of the challenges of microlensing is its one-time nature; each event is unrepeatable, making follow-up observations impossible. However, this limitation is also a strength, as it allows for the detection of planets around stars thousands of light-years away, far beyond the reach of other methods like transit or radial velocity. For example, in 2017, microlensing revealed a rocky planet just 40% larger than Earth orbiting a low-mass star 2,500 light-years away. Such discoveries highlight the method’s potential to uncover Earth-like planets in distant regions of the galaxy.

Practical tips for amateur astronomers interested in microlensing include joining citizen science projects that analyze microlensing data, such as the Einstein@Home project. While amateurs cannot conduct their own microlensing observations due to the need for specialized equipment and continuous monitoring, they can contribute to data analysis and help identify planetary signals. For professionals, collaboration with established microlensing surveys and access to high-cadence telescopes are essential. Future missions, like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, promise to expand microlensing’s capabilities, potentially detecting thousands of exoplanets and refining our understanding of planetary systems across the galaxy.

In the quest to find alien planets, microlensing stands out as a method that bridges the gap between nearby and distant worlds. Its ability to detect low-mass planets in wide orbits complements other techniques, offering a fuller picture of exoplanetary diversity. While it may not provide detailed atmospheric data or repeated observations, microlensing’s reach and sensitivity make it an indispensable tool in the search for Earth-like planets in the vastness of space. By observing these fleeting cosmic events, we inch closer to answering the age-old question: Are we alone in the universe?

Listeria Species: Do They Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Astrometry: Track star movements precisely to infer orbiting planets' presence indirectly

Stars, despite their immense size, are not stationary. They wobble ever so slightly, influenced by the gravitational pull of orbiting planets. Astrometry, the precise measurement of stellar positions, leverages this subtle dance to reveal hidden worlds. By tracking a star's minuscule deviations from its expected path, astronomers can infer the presence of unseen companions, even if those companions are too faint or distant to be directly observed.

Think of it as deducing the presence of a hidden weight on a pendulum by observing its altered swing.

This method, while conceptually elegant, demands extraordinary precision. Traditional astrometry relied on photographic plates and manual measurements, limiting its sensitivity. Modern advancements, however, have revolutionized the field. Space-based telescopes like Gaia, equipped with ultra-sensitive instruments, can measure stellar positions with astonishing accuracy, detecting movements as small as a few microarcseconds – roughly the width of a human hair seen from 10 kilometers away. This level of precision allows astronomers to detect planets with masses comparable to Earth orbiting at distances similar to those in our own solar system.

Moreover, astrometry excels at identifying long-period planets, those with orbital times spanning decades or even centuries, which are often missed by other detection methods.

Despite its power, astrometry is not without challenges. The technique is particularly sensitive to instrumental errors and atmospheric distortions. Careful calibration and data analysis are crucial to distinguish planetary signals from noise. Additionally, astrometry is most effective for detecting massive planets orbiting relatively close to their stars. Smaller, Earth-like planets at greater distances remain elusive, requiring even more advanced instruments and longer observation periods.

The future of astrometry holds immense promise. Upcoming missions like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will further enhance our ability to detect Earth-sized planets in the habitable zones of nearby stars. By combining astrometry with other techniques like radial velocity and transit photometry, astronomers are poised to paint a more complete picture of the planetary systems that populate our galaxy, bringing us closer to answering the age-old question: Are we alone in the universe?

How to Delete Phone Numbers on a Santa Fe Spore

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

To find alien planets in Spore, you need to progress to the Space Stage. Once you have a spaceship, explore the galaxy by clicking on star systems in the galactic map. Each system may contain habitable or alien planets.

Use the "Scan Planet" tool in the Space Stage to analyze planets for life signs. Planets with alien life will show green or red indicators, depending on whether the life is friendly or hostile.

Yes, once you locate an alien planet, you can land on it to explore, meet indigenous species, and even trade or engage in combat, depending on the planet's inhabitants.

Alien planets vary in size, atmosphere, and life forms. Look for planets with green or red indicators during scanning, as these signify the presence of alien life. T-class planets are particularly notable for hosting advanced civilizations.