Fly agaric mushrooms, scientifically known as *Amanita muscaria*, are iconic fungi recognized by their bright red caps dotted with white flakes. To find these distinctive mushrooms, focus on temperate and boreal forests, particularly in regions like North America, Europe, and Asia. They often grow in symbiotic relationships with birch, pine, and spruce trees, so search in areas with these species. Fly agarics typically appear in late summer to early autumn, thriving in moist, well-drained soil. Look for them in open woodlands, along forest edges, or near tree bases, where they emerge singly or in small clusters. Always exercise caution, as they are psychoactive and can be toxic if ingested improperly. Proper identification is crucial to avoid confusion with similar-looking species.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identify Habitat: Look for coniferous forests, birch trees, mossy areas, and cool, moist environments

- Seasonal Timing: Hunt in late summer to early autumn when fruiting bodies appear

- Distinct Features: Recognize bright red cap, white spots, and distinct umbrella shape

- Avoid Lookalikes: Differentiate from poisonous imposters like Amanita muscaria var. guessowii

- Ethical Foraging: Harvest sustainably, leaving some mushrooms to spore and regenerate

Identify Habitat: Look for coniferous forests, birch trees, mossy areas, and cool, moist environments

Fly agaric mushrooms, scientifically known as *Amanita muscaria*, thrive in specific habitats that are as distinctive as their vibrant red caps dotted with white flakes. To locate these iconic fungi, focus on coniferous forests, where the symbiotic relationship between the mushrooms and trees like spruce, pine, and fir creates an ideal environment. These forests provide the acidic soil and shaded canopy that fly agarics prefer, making them a prime hunting ground for foragers.

Birch trees are another critical indicator of fly agaric presence. Often found in mixed woodlands, birch trees form a mycorrhizal association with these mushrooms, meaning the fungi help the trees absorb nutrients while the trees provide carbohydrates in return. Look for clusters of fly agarics at the base of birch trees, especially in regions where these trees dominate the understory. This mutualistic relationship is a reliable clue for foragers seeking these mushrooms.

Mossy areas further enhance the likelihood of finding fly agarics. These mushrooms favor damp, organic-rich soil, often covered in a layer of moss that retains moisture and moderates temperature. Moss acts as a natural sponge, keeping the environment cool and humid—conditions fly agarics require to flourish. Foraging in mossy patches, particularly in shaded areas, increases your chances of a successful find.

Cool, moist environments are non-negotiable for fly agarics. These mushrooms are sensitive to heat and dryness, so they typically appear in late summer to early autumn when temperatures drop and humidity rises. Avoid areas exposed to direct sunlight or prone to drought. Instead, seek out low-lying regions near streams, ravines, or north-facing slopes where moisture is abundant and temperatures remain consistently cool.

To maximize your foraging success, combine these habitat clues. Start by locating coniferous forests or birch groves, then narrow your search to mossy, shaded areas within these zones. Time your expedition during cooler, wetter months, and carry a field guide to confirm identification, as fly agarics can resemble other red-capped species. Remember, while these mushrooms are culturally iconic, they are psychoactive and potentially toxic, so proper identification and caution are essential.

Discovering Wavy Cap Mushrooms: Top Spots for Foraging Success

You may want to see also

Seasonal Timing: Hunt in late summer to early autumn when fruiting bodies appear

The fly agaric mushroom, with its iconic red cap and white spots, is a sight to behold, but its appearance is fleeting. These fungi are not year-round residents of the forest floor; they emerge during a specific window, typically from late summer to early autumn. This seasonal timing is crucial for foragers, as it dictates when to venture into the woods with basket in hand. Understanding this natural cycle not only increases your chances of a successful hunt but also ensures you’re respecting the mushroom’s life stages.

From an ecological perspective, the fruiting bodies of fly agaric mushrooms appear as a response to environmental cues, primarily temperature and moisture. As summer transitions to autumn, cooler nights and increased rainfall create the ideal conditions for mycelium—the underground network of fungal threads—to produce these visible mushrooms. This period is short-lived, often lasting only a few weeks, making timing essential. Foragers in regions with distinct seasons should mark their calendars for late August through October, though local microclimates can shift this slightly.

For those new to mushroom hunting, here’s a practical tip: pair your search with other autumn activities, like leaf-peeping or hiking. Fly agarics often grow in symbiotic relationships with birch, pine, and spruce trees, so focus your efforts in coniferous or mixed woodlands. Carry a small trowel to gently uncover specimens hidden under leaf litter, and always leave some behind to allow spores to disperse, ensuring future generations. Avoid areas treated with pesticides or near busy roads, as these can contaminate the mushrooms.

A comparative analysis of seasonal foraging reveals why autumn is superior for fly agarics. Spring, dominated by morels and ramps, lacks the moisture needed for these mushrooms. Winter’s frost renders the ground inhospitable, while summer’s heat and dryness suppress fruiting. Autumn, however, strikes a balance—cool enough to stimulate growth, wet enough to sustain it. This seasonality also aligns with the lifecycle of the trees they depend on, creating a harmonious ecological rhythm.

Finally, a persuasive argument for respecting this seasonal window: foraging outside of late summer to early autumn not only yields poor results but also disrupts the mushroom’s reproductive cycle. Overharvesting or mistiming your hunt can weaken mycelium networks, reducing future fruiting. By adhering to this natural schedule, you become a steward of the forest, ensuring these striking fungi continue to thrive. So, mark your calendar, sharpen your observation skills, and embrace the ephemeral beauty of the fly agaric in its prime.

Discover the Perfect Music for Your Mushroom Playlist: Top Sources

You may want to see also

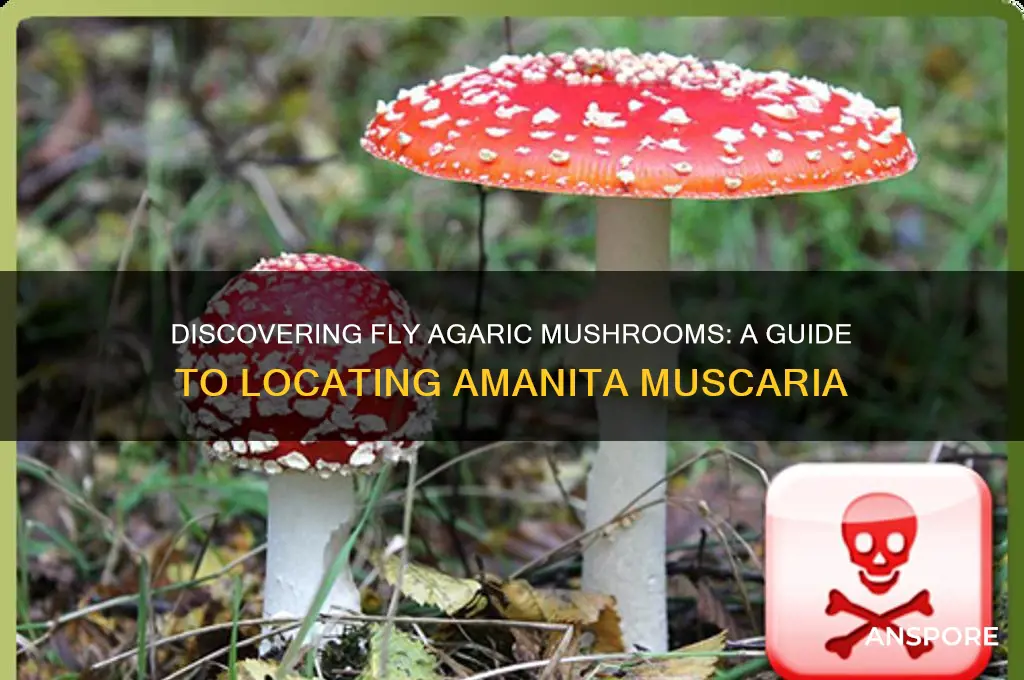

Distinct Features: Recognize bright red cap, white spots, and distinct umbrella shape

The fly agaric mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita muscaria*, is instantly recognizable due to its vibrant red cap, which stands out like a beacon in forested areas. This cap, often ranging from 8 to 20 cm in diameter, is not just red but a deep, fiery hue that can vary slightly depending on environmental conditions. The color alone is a primary identifier, but it’s the combination of this vivid red with its distinct features that makes it unmistakable. For foragers, this is your first clue—look for a splash of red among the greens and browns of the forest floor.

White spots, or warts, are another defining characteristic of the fly agaric. These are remnants of the universal veil, a protective layer that encases the mushroom during its early development. As the cap expands, the veil breaks apart, leaving behind these distinctive patches. The contrast between the bright red cap and the pure white spots is striking, making the mushroom easy to spot even from a distance. However, be cautious: these spots can wash off in rainy conditions, so a clean red cap doesn’t necessarily rule out a fly agaric. Always look for other features to confirm your find.

The umbrella-like shape of the fly agaric is its third unmistakable trait. The cap is convex when young, gradually flattening with age, and often has a slightly raised center. This shape, combined with the red cap and white spots, creates a silhouette that’s hard to confuse with other mushrooms. For beginners, practice by comparing photos of fly agarics to other red-capped species like *Amanita jacksonii* or *Rubinoboletus* species, which lack the white spots and distinct shape. Familiarizing yourself with these differences will sharpen your identification skills.

While the fly agaric’s appearance is iconic, it’s crucial to approach it with respect. This mushroom is psychoactive and contains compounds like muscimol and ibotenic acid, which can cause hallucinations, nausea, and disorientation if ingested. Foraging for it should only be done for identification or photographic purposes unless you’re an experienced mycologist or working under expert guidance. Even then, proper dosage and preparation are essential—a single cap can contain enough active compounds to induce effects, and misidentification can lead to severe poisoning.

In practical terms, the best time to find fly agarics is late summer to early autumn, particularly in coniferous and deciduous forests with birch, pine, or spruce trees. They often grow in symbiotic relationships with these trees, so focus your search in areas where their roots are abundant. Carry a field guide or use a mushroom identification app to cross-reference your findings, and always collect samples responsibly, leaving most mushrooms undisturbed to ensure their ecological role continues. Recognizing the fly agaric’s bright red cap, white spots, and umbrella shape is just the beginning—understanding its habitat and handling it safely completes the picture.

Discovering the Elusive Black Mushroom: Top Locations and Hunting Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Avoid Lookalikes: Differentiate from poisonous imposters like Amanita muscaria var. guessowii

The vibrant red cap and white flecks of the fly agaric mushroom (Amanita muscaria) are unmistakable, but its doppelgängers lurk in the same forests. One such imposter, Amanita muscaria var. guessowii, shares a striking resemblance but harbors toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress or worse. Misidentification can turn a foraging expedition into a dangerous gamble, making it crucial to master the subtle distinctions between these fungi.

Begin by examining the cap’s color and texture. While both varieties sport a red cap, var. guessowii often displays a deeper, almost burgundy hue compared to the brighter red of the classic fly agaric. The white flecks, or warts, on var. guessowii tend to be more densely clustered and less prone to washing off with rain. However, these visual cues alone are not foolproof, as environmental factors can influence appearance. A hand lens can reveal finer details, such as the arrangement of warts or the texture of the cap’s surface, but even this requires practice to interpret accurately.

Gills and stem characteristics offer more reliable clues. The gills of Amanita muscaria are typically white and closely spaced, while var. guessowii may show a slight yellowish tint or broader spacing. The stem of var. guessowii often lacks the prominent bulbous base of its cousin, instead tapering more uniformly. Additionally, the partial veil remnants—the skirt-like ring on the stem—can differ in thickness and persistence between the two. These features, though subtle, can be decisive when combined with other observations.

Habitat and seasonality play a supporting role in identification. Both varieties thrive in coniferous and deciduous forests, often forming mycorrhizal relationships with birch or pine trees. However, var. guessowii is more commonly found in North America, particularly in the eastern United States, whereas Amanita muscaria has a broader global distribution. Foraging during peak seasons—late summer to early fall—increases the likelihood of encountering both species, but it also heightens the risk of confusion. Always cross-reference multiple field guides or consult an expert if uncertainty persists.

Ultimately, the safest approach is to avoid consumption altogether unless you are absolutely certain of your identification. Even experienced foragers rely on a combination of visual, ecological, and microscopic analysis to distinguish these lookalikes. Carrying a spore print kit can provide additional confirmation, as the spore color of var. guessowii may differ slightly from its more famous relative. Remember, the goal is not just to find fly agaric mushrooms but to do so without risking your health—a task that demands patience, precision, and respect for the complexity of the fungal world.

Discovering Magic Mushrooms in New York: Top Spots and Tips

You may want to see also

Ethical Foraging: Harvest sustainably, leaving some mushrooms to spore and regenerate

Fly agaric mushrooms, with their iconic red caps and white spots, are a symbol of both fascination and caution in the foraging world. While their psychoactive properties draw curiosity, sustainable harvesting is crucial to preserve their ecological role and ensure future abundance. Ethical foraging isn’t just a practice—it’s a responsibility. By leaving some mushrooms to mature and release spores, you contribute to the regeneration of the species and the health of the forest ecosystem.

Consider this: a single mature fly agaric can release billions of spores, each with the potential to grow into a new mushroom. When foraging, adopt the "one-third rule"—harvest no more than one-third of the mushrooms in a patch, leaving the rest to spore. This ensures the population remains robust. Additionally, avoid picking young, immature specimens, as they haven’t yet contributed to the spore cycle. Focus on older mushrooms with caps that are fully open or slightly upturned, as these are past their prime for consumption but ideal for spore dispersal.

The forest floor is a delicate tapestry, and fly agaric mushrooms play a vital role in nutrient cycling and mycorrhizal relationships with trees. Overharvesting disrupts this balance, threatening not just the mushrooms but the entire ecosystem. For instance, birch trees, a common symbiont of fly agarics, rely on these fungi for nutrient uptake. By foraging ethically, you protect these relationships and maintain the biodiversity of the woodland.

Practical tips can make ethical foraging second nature. Carry a small knife to cut mushrooms at the base, minimizing damage to the mycelium. Avoid stepping on surrounding vegetation, as this can compact the soil and harm underground fungal networks. Keep a foraging journal to track locations and harvest quantities, ensuring you don’t over-collect from the same area. Finally, educate fellow foragers—sharing knowledge about sustainable practices amplifies the impact of your efforts.

In the end, ethical foraging of fly agaric mushrooms is about balance—taking what you need while ensuring the species thrives. It’s a mindful approach that respects the interconnectedness of nature. By leaving some mushrooms to spore and regenerate, you’re not just preserving a resource; you’re honoring the forest’s ability to sustain life for generations to come.

Discover Maine's Best Morel Mushroom Hunting Spots and Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fly agaric mushrooms (Amanita muscaria) typically appear in late summer to early autumn, often coinciding with cooler, moist weather. Look for them from August to October in the Northern Hemisphere.

Fly agarics are mycorrhizal fungi, meaning they form symbiotic relationships with trees. They are commonly found in coniferous and deciduous forests, particularly under birch, pine, and spruce trees. Look for them in mossy, shaded areas with well-drained soil.

Fly agarics are distinctive with their bright red caps covered in white flecks (remnants of the universal veil). They have white gills and a bulbous base. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert, as they resemble some toxic species. Never consume them without proper identification and knowledge of their psychoactive properties.