Finding mushrooms on dead trees, also known as standing deadwood or snags, requires a keen eye and an understanding of fungal habitats. These trees, often overlooked, provide an ideal environment for various mushroom species to thrive due to their decaying wood, which is rich in nutrients. To locate mushrooms, start by identifying dead or dying trees in your area, particularly those with visible signs of decay like cracks, holes, or peeling bark. Different mushroom species prefer specific tree types, so knowing the local tree species can be advantageous. Early morning or after rain is the best time to search, as mushrooms tend to be more visible and abundant during these periods. Look for colorful caps or unusual growths on the tree's trunk, branches, or base, as these are telltale signs of mushroom presence. Remember, some mushrooms are toxic, so proper identification is crucial before considering consumption.

Explore related products

$16.63 $20

$14.8 $22.95

What You'll Learn

- Identify suitable tree species for mushroom growth, such as oak, beech, or maple

- Look for signs of decay, including cracks, holes, or fungal growth on the tree

- Check the tree's base and surrounding soil for mushroom fruiting bodies

- Observe the tree's environment, including sunlight, moisture, and nearby vegetation

- Learn to recognize common mushroom species that grow on dead trees, like oyster mushrooms

Identify suitable tree species for mushroom growth, such as oak, beech, or maple

Dead trees, often overlooked in the forest, are hotspots for mushroom growth, but not all species are created equal. Certain trees, like oak, beech, and maple, provide ideal conditions for fungi to thrive due to their wood composition and decomposition rates. Oak, for instance, is rich in tannins, which can inhibit some fungi but create a niche environment for specialized species like the prized lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*). Beech trees, with their dense, slow-to-decay wood, often host bracket fungi such as the turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*). Maple, with its softer wood, decomposes more quickly, attracting fast-growing mushrooms like oyster (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). Understanding these relationships is the first step in pinpointing where mushrooms are likely to appear.

To identify suitable trees, start by examining the bark and wood texture. Oak bark is deeply furrowed, while beech bark is smooth and gray, and maple bark varies from smooth to ridged depending on age. Look for signs of decay, such as cracks, hollows, or soft spots, which indicate the tree is in an advanced stage of decomposition—prime territory for mushrooms. Foraging in areas with a mix of these species increases your chances of finding a variety of fungi. Pro tip: Bring a small hand lens to inspect the wood grain and fungal mycelium, which often appears as white threads beneath the bark.

While oak, beech, and maple are reliable candidates, not all individuals of these species will host mushrooms. Focus on older, dead, or dying trees, as they provide the nutrients and structure fungi need to fruit. Avoid freshly fallen trees, as they haven’t had time to decompose sufficiently. Instead, seek out standing deadwood (snags) or fallen logs that have been on the forest floor for at least a year. A cautionary note: Be mindful of safety when approaching dead trees, as they can be unstable. Always assess the risk before getting too close.

Comparing these tree species reveals why they’re favored by different mushrooms. Oak’s hardness and chemical composition support fungi that can break down lignin, a complex polymer in wood. Beech’s density slows decomposition, creating a long-lasting habitat for perennial fungi. Maple’s softer wood decomposes faster, providing a quick energy source for opportunistic mushrooms. By observing these patterns, you can predict which fungi are likely to appear on each tree type. For example, if you spot a cluster of oyster mushrooms, chances are you’re near a maple.

Finally, seasonality plays a role in mushroom growth on these trees. Spring and fall are peak seasons, with cooler temperatures and higher humidity encouraging fruiting. In summer, look for mushrooms in shaded, moist areas near these trees. Winter can still yield surprises, particularly with species like lion’s mane, which often fruits in colder months. Keep a foraging journal to track which trees produce mushrooms and when, refining your ability to locate them year after year. With practice, identifying suitable tree species will become second nature, transforming your forest walks into a treasure hunt for fungi.

Discover Snake Head Mushroom Wukong: Top Locations and Hunting Tips

You may want to see also

Look for signs of decay, including cracks, holes, or fungal growth on the tree

Dead trees, often overlooked in the forest, are treasure troves for mushroom hunters. The key to uncovering these fungal gems lies in recognizing the subtle yet telling signs of decay. Cracks, holes, and fungal growth are not merely indicators of a tree’s demise but also signals of the perfect environment for mushrooms to thrive. These features create pockets of moisture and nutrients, fostering the conditions mycelium—the vegetative part of a fungus—needs to fruit into mushrooms. By learning to spot these signs, you transform a casual woodland stroll into a targeted search for edible or medicinal fungi.

Analyzing the tree’s surface is the first step in this process. Cracks, particularly those that run deep into the bark, are prime locations for mycelium to establish itself. These fissures often retain moisture longer than the surrounding wood, creating a microclimate conducive to fungal growth. Holes, whether caused by insects or rot, serve a similar purpose. They provide entry points for spores and shelter for developing mycelium. A tree riddled with such imperfections is far more likely to host mushrooms than one with smooth, intact bark.

However, not all decay is created equal. Fungal growth on the tree itself—such as bracket fungi or conks—is a particularly strong indicator of mushroom potential. These wood-decay fungi break down the tree’s structure, releasing nutrients into the surrounding environment. While they may not always be the same species as the mushrooms you seek, their presence suggests the tree is in an advanced stage of decomposition, ideal for a variety of fungi. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) often appear on trees already colonized by other wood-decay fungi.

Practical tips can enhance your search. Carry a small tool, like a knife or awl, to gently probe cracks and holes for hidden mycelium. Look for trees with a mix of decay types—a combination of cracks, holes, and visible fungal growth increases the likelihood of finding mushrooms. Seasonality matters too; late summer and fall are prime times, as cooler, wetter weather triggers fruiting. Avoid trees in early stages of decay, as they may not yet support a robust fungal ecosystem.

In conclusion, mastering the art of identifying decay signs transforms dead trees from obstacles into opportunities. By focusing on cracks, holes, and existing fungal growth, you narrow your search area and increase your chances of success. This methodical approach not only makes mushroom hunting more efficient but also deepens your understanding of the intricate relationship between fungi and their environment. Armed with this knowledge, you’ll find that even the most unassuming dead tree can yield a surprising bounty.

Discover Arizona's Best Spots for Edible Mushroom Foraging

You may want to see also

Check the tree's base and surrounding soil for mushroom fruiting bodies

Mushrooms often emerge from the base of dead or decaying trees, where the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—has colonized the wood. This area is a prime location for fruiting bodies to sprout, as the tree’s decomposition provides nutrients and moisture. When inspecting a tree, kneel or bend to examine the lowest 12–18 inches of the trunk and the immediate soil around it. Look for clusters or solitary mushrooms, which may appear as small bumps, caps, or gills depending on their growth stage. A flashlight or magnifying glass can help spot subtle signs of fungal activity in low-light conditions.

The soil surrounding a dead tree is another critical zone to explore. Mushrooms often grow here because the mycelium extends outward from the tree, breaking down organic matter in the ground. Use a trowel or your hands to gently dig into the top 2–3 inches of soil, where fruiting bodies may be hidden beneath leaves or debris. Be mindful of the soil’s texture—moist, crumbly earth is more conducive to mushroom growth than dry, compacted dirt. If the soil smells earthy or slightly fungal, it’s a good indicator that mushrooms may be present or developing underground.

While searching, consider the tree species and its stage of decay. Hardwoods like oak, beech, and maple are particularly attractive to fungi, as their dense wood provides ample nutrients. Softwoods like pine may also host mushrooms, but the species are often different. A tree in advanced decay—with crumbling bark, hollows, or visible wood fibers—is more likely to support fruiting bodies than one recently fallen. However, even freshly dead trees can show early signs of fungal colonization, so don’t overlook them entirely.

Practical tips can enhance your search efficiency. Wear gloves to protect your hands from splinters and soil-borne irritants. Carry a small brush to gently clean mushrooms for identification without damaging them. Note the color, shape, and texture of any fruiting bodies you find, as these details are crucial for species identification. Avoid disturbing the surrounding area excessively, as this can harm the mycelium and reduce future fruiting potential. Finally, always cross-reference your findings with a reliable field guide or app to ensure safe and accurate identification.

Discovering Matsutake Mushrooms: Expert Tips for Finding This Elusive Delicacy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.53 $39.95

Observe the tree's environment, including sunlight, moisture, and nearby vegetation

Sunlight, moisture, and surrounding vegetation form a silent dialogue that mushrooms heed. Dead trees don’t exist in isolation; they’re part of an ecosystem where these elements dictate fungal presence. Observe sunlight patterns: mushrooms thrive in dappled or indirect light, as direct sun can desiccate delicate mycelium. A north-facing slope or forest understory often provides the ideal balance. Moisture is equally critical; look for trees near streams, damp depressions, or areas with consistent dew. However, avoid waterlogged zones, as excessive moisture can drown mycelial networks. Nearby vegetation matters too: certain plants, like ferns or mosses, signal a microclimate conducive to fungal growth. Conversely, dense grass can compete for resources, reducing mushroom yields.

To systematically assess these factors, start by mapping sunlight exposure throughout the day. Use a compass to identify cardinal directions and note how light filters through the canopy. For moisture, check the soil: it should be damp to the touch but not muddy. A simple test is to squeeze a handful—if water drips, it’s too wet; if it crumbles, it’s too dry. Vegetation analysis requires familiarity with indicator species. For instance, bracket fungi often coexist with oyster mushrooms, while chanterelles favor beech or oak forests. Carry a field guide or app to identify symbiotic relationships.

Consider the tree’s stage of decay. Freshly fallen logs lack the nutrients mushrooms need, while overly decomposed wood may have already exhausted its fungal potential. The “Goldilocks zone” is wood soft enough to dent with a thumb but still retaining structure. Pair this with optimal environmental conditions, and you’ll maximize your chances. For example, a dead aspen in partial shade, near a moss-covered stream, is a prime candidate for morels or lion’s mane.

Caution: not all environments are created equal. Avoid areas treated with pesticides or near industrial runoff, as toxins can accumulate in fungi. Similarly, invasive plant species can disrupt native fungal communities. Always cross-reference your findings with local mycological resources or experts. While observing the environment is a powerful tool, it’s just one piece of the puzzle—combine it with knowledge of fruiting seasons and tree species for a comprehensive approach.

In practice, think like a detective. A dead oak in full sun is less promising than one in a fern-lined ravine. A maple near a leaky creek might host turkey tail mushrooms, while a pine in an open meadow likely won’t. By synthesizing sunlight, moisture, and vegetation cues, you’ll develop an intuition for where mushrooms hide. Remember, fungi are opportunists—they exploit niches where conditions align. Your task is to learn their language and follow the clues they leave in the environment.

Identifying Bluing in Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide to Foraging Safely

You may want to see also

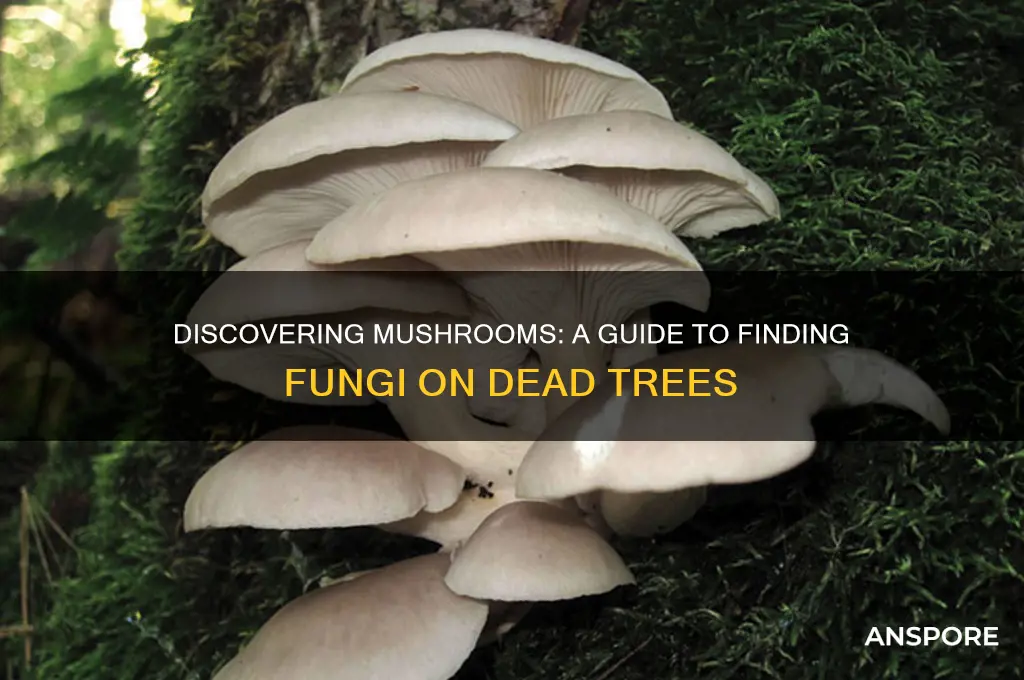

Learn to recognize common mushroom species that grow on dead trees, like oyster mushrooms

Dead trees, often overlooked, are treasure troves for foragers seeking mushrooms. Among the most sought-after species are oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which thrive on decaying wood. Recognizing these mushrooms begins with understanding their habitat: they favor hardwoods like beech, oak, and maple, though they can also grow on conifers. Look for trees with bark that’s cracked, softened, or peeling—signs of advanced decay that oysters love. Their fan-shaped caps, ranging from gray to brown, often grow in clusters, resembling overlapping shells. A key identifier is their gills, which run down the stem, a trait not all mushrooms share.

To spot oysters effectively, time your search to late summer through fall, their peak season. However, they can appear in spring if conditions are damp and cool. Carry a small knife and basket, not a plastic bag, to avoid damaging the mushrooms or hastening spoilage. When harvesting, twist the stem gently to preserve the mycelium, allowing future growth. Avoid specimens growing near roadsides or polluted areas, as mushrooms absorb toxins readily. Always cross-reference your find with a field guide or app like *Mushroom Observer* to confirm identification, as look-alikes like the elm oyster (*Hypsizygus ulmarius*) are edible but differ slightly in appearance.

Beyond oysters, dead trees host other notable species. The turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*) is a bracket fungus with colorful, layered caps, though it’s medicinal rather than edible. Chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureos*) appears as bright orange-yellow shelves and is a culinary favorite, but caution is advised—it can cause reactions in some people, especially when undercooked. Compare these to the artist’s conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), which has a varnished brown cap and is inedible but useful for natural dyeing. Each species has unique characteristics, so study their textures, colors, and growth patterns to avoid confusion.

Mastering identification requires practice and patience. Start by focusing on one species at a time, using detailed guides like *National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms*. Join local foraging groups or workshops to learn from experienced foragers. Document your finds with photos and notes, noting the tree type, location, and environmental conditions. Over time, you’ll develop an eye for subtle differences, like the slightly fuzzy cap edge of oysters or the zoned coloration of chicken of the woods. Remember, misidentification can be dangerous, so when in doubt, leave it out.

Finally, ethical foraging is as important as accurate identification. Only take what you need, leaving enough mushrooms to spore and regenerate. Avoid damaging the tree or surrounding habitat, and never uproot entire clusters. By respecting nature’s balance, you ensure these species thrive for future foragers. With knowledge, caution, and care, recognizing and harvesting mushrooms from dead trees becomes a rewarding skill, connecting you to the forest’s hidden bounty.

Discover the Perfect Music for Your Mushroom Playlist: Top Sources

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Deciduous trees like oak, beech, and maple are commonly associated with mushroom growth, especially species like oyster mushrooms and turkey tail. Coniferous trees like pine and spruce can also host mushrooms such as chaga and birch polypore.

Look for signs of decay, such as cracked or peeling bark, soft wood, and the presence of wood-eating insects. Mushrooms often grow on trees that are in advanced stages of decomposition or have been damaged by disease or injury.

Mushrooms on dead trees are most commonly found in late summer, fall, and early winter, as cooler, damp conditions promote fungal growth. However, some species, like oyster mushrooms, can also appear in spring.