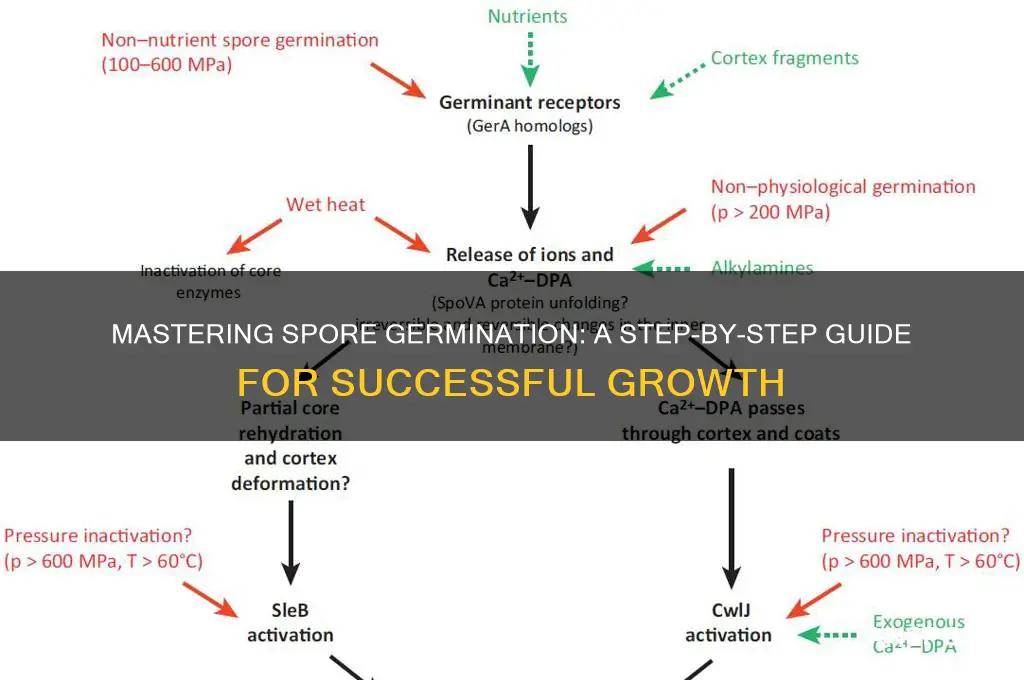

Germinating spores is a fascinating process that marks the beginning of a fungus's life cycle, requiring specific conditions to transition from dormancy to active growth. Spores, which are highly resilient and can survive in harsh environments, need a combination of moisture, warmth, and a suitable substrate to initiate germination. Typically, the process begins by hydrating the spores, often in a sterile water solution, followed by transferring them to a nutrient-rich medium like agar or soil. Maintaining optimal temperature, usually between 20-28°C (68-82°F), and ensuring proper humidity are critical for success. Additionally, some spores may require specific triggers, such as light or chemical signals, to break dormancy. Understanding these requirements is essential for cultivating fungi, whether for scientific research, agriculture, or mycological hobbyists.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Optimal Temperature | 20-30°C (68-86°F) for most species; some require specific ranges. |

| Light Requirement | Indirect light or darkness, depending on species. |

| Moisture | High humidity (90-100%) is essential; substrate must remain moist. |

| Substrate | Sterilized organic matter (e.g., agar, soil, or wood chips). |

| Nutrients | Minimal nutrients required; often provided by the substrate. |

| Oxygen | Adequate airflow is necessary to prevent contamination. |

| pH Level | Slightly acidic to neutral (pH 5.5-7.0) for most species. |

| Sterilization | Substrate and equipment must be sterilized to prevent contamination. |

| Time to Germination | Varies by species, typically 1-4 weeks. |

| Contamination Prevention | Use sterile techniques, such as flame sterilization and clean workspaces. |

| Species-Specific Needs | Some spores require specific triggers (e.g., cold shock or scarification). |

| Storage Conditions | Spores can be stored in a cool, dark place (e.g., refrigerator) for years. |

| Hydration | Spores must be hydrated before germination; often done with sterile water. |

| Inoculation Method | Spores are typically inoculated onto a sterile substrate using a syringe. |

| Monitoring | Regularly check for signs of growth or contamination. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal Temperature Range: Spores germinate best within specific temperature ranges, varying by species

- Moisture Requirements: Consistent moisture is crucial for spore germination; avoid over or under-watering

- Light Conditions: Some spores require light to trigger germination, while others prefer darkness

- Substrate Preparation: Use sterile, nutrient-rich substrates like agar or soil for successful germination

- Sterilization Techniques: Prevent contamination by sterilizing tools, containers, and substrates before use

Optimal Temperature Range: Spores germinate best within specific temperature ranges, varying by species

Temperature is a critical factor in spore germination, acting as a trigger that signals to dormant spores that conditions are favorable for growth. Each spore species has evolved to respond to specific temperature ranges, often tied to their natural habitat. For example, spores of certain mushroom species, like * Psilocybe cubensis*, typically germinate optimally between 24°C and 28°C (75°F and 82°F), mirroring the warm, humid environments where they thrive in the wild. Understanding these species-specific ranges is essential for successful germination, whether for mycological research, cultivation, or ecological studies.

To harness the power of temperature for spore germination, precise control is key. For most fungal spores, a consistent temperature within their optimal range accelerates the germination process, often reducing the time from days to hours. However, deviations from this range can inhibit germination or even kill the spores. For instance, temperatures above 35°C (95°F) can denature enzymes essential for spore activation, while temperatures below 15°C (59°F) may slow metabolic processes to a halt. Using tools like heating mats, incubators, or even simple thermostats can help maintain the necessary conditions, ensuring spores receive the thermal cue they need to awaken from dormancy.

Comparing spore species highlights the diversity in temperature requirements and the importance of tailoring conditions to each type. For example, *Aspergillus* spores often germinate best at temperatures between 25°C and 37°C (77°F and 98.6°F), reflecting their adaptability to both environmental and host-associated niches. In contrast, spores of certain lichen-forming fungi may require cooler temperatures, such as 10°C to 20°C (50°F to 68°F), to mimic their alpine or boreal habitats. This variability underscores the need for research or reference guides to determine the optimal temperature range for the specific spores being cultivated, avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach.

Practical tips for achieving optimal temperatures include monitoring both ambient and substrate temperatures, as spores often require warmth at the point of contact with their growth medium. For small-scale projects, placing spore-inoculated substrates in sealed containers with a heat source can create a microclimate conducive to germination. For larger operations, automated climate control systems can maintain precise temperatures across entire grow rooms. Additionally, gradual temperature adjustments can mimic natural conditions, such as the warming of soil in spring, potentially enhancing germination rates. By respecting the unique thermal preferences of each spore species, cultivators can maximize success and unlock the full potential of these microscopic powerhouses.

Troubleshooting Spore Registration Issues: Common Problems and Quick Fixes

You may want to see also

Moisture Requirements: Consistent moisture is crucial for spore germination; avoid over or under-watering

Spores, those resilient microscopic survivalists, awaken from dormancy only when conditions are just right. Moisture, the lifeblood of germination, must be meticulously managed. Too little, and the spore remains dormant, its potential locked away. Too much, and you risk drowning it, fostering rot instead of life. This delicate balance demands attention, for it is the cornerstone of successful spore germination.

Understanding the moisture needs of spores requires a shift in perspective. Unlike seeds, which often require a period of dryness before germination, spores thrive in consistently damp environments. This is because they lack the protective seed coat and stored nutrients, relying instead on external conditions to trigger growth. Imagine a desert flower blooming after a rare rain – that’s the level of moisture sensitivity we’re dealing with.

Achieving this balance involves more than just watering. Consider the substrate, the medium in which spores are sown. Materials like vermiculite, perlite, or agar gels are popular choices due to their ability to retain moisture without becoming waterlogged. A common technique is the "misting method," where the substrate is lightly sprayed with water several times a day to maintain a humid environment. For more precise control, some cultivators use humidity domes or sealed containers to create a mini-greenhouse effect, ensuring the spores are surrounded by moisture-rich air.

However, even with these methods, over-watering remains a constant threat. Excess moisture can lead to the growth of competing molds and bacteria, which can outcompete the spores for resources. To mitigate this, ensure proper ventilation and avoid saturating the substrate. A good rule of thumb is to maintain the substrate at a moisture level similar to a wrung-out sponge – damp but not dripping.

The age and species of the spore also play a role in moisture requirements. Fresh spores, harvested within the past year, generally germinate more readily and may require slightly higher humidity levels. Older spores, while still viable, may need a more controlled environment to overcome their natural dormancy. Researching the specific needs of the spore species you’re working with can provide valuable insights into optimal moisture conditions.

In conclusion, mastering moisture is an art in spore germination. It demands a combination of careful observation, precise technique, and an understanding of the spore’s unique biology. By maintaining consistent moisture without over-saturating the environment, you create the ideal conditions for these microscopic powerhouses to awaken and thrive. Remember, in the world of spores, moisture is not just a requirement – it’s the key that unlocks their potential.

Transitioning Your Spore Creature: Carnivore to Omnivore Diet Guide

You may want to see also

Light Conditions: Some spores require light to trigger germination, while others prefer darkness

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, plants, and some bacteria, exhibit a fascinating dichotomy in their response to light. For some, light acts as a crucial signal, triggering the metabolic processes necessary for germination. Others, however, thrive in darkness, where the absence of light initiates their growth. Understanding this light-dependent behavior is essential for successfully cultivating spores, whether for scientific research, horticulture, or mycological exploration.

Consider the *Physarum polycephalum*, a slime mold whose spores germinate optimally under continuous low-intensity light (around 10–20 μmol/m²/s). This species relies on light to activate photoreceptors, which in turn stimulate enzyme activity and break dormancy. Conversely, spores of certain mushroom species, like *Stropharia rugosoannulata*, prefer complete darkness. Exposing these spores to light, even briefly, can inhibit germination by disrupting their internal circadian rhythms. To cater to such preferences, cultivators often use opaque containers or cover petri dishes with aluminum foil to ensure a light-free environment.

The mechanism behind light-dependent germination often involves phytochrome proteins, which detect light and trigger downstream signaling pathways. For light-requiring spores, a brief exposure to red light (660 nm) followed by far-red light (730 nm) can mimic natural conditions and enhance germination rates. This technique, known as "light pulsing," is particularly effective for species like *Ceratopteris richardii*, a fern whose spores respond dramatically to this treatment. Conversely, for darkness-preferring spores, maintaining a consistent light-free environment is critical. Even ambient room light can interfere, so storing spore containers in dark cabinets or using blackout materials is advisable.

Practical application of this knowledge requires precision. For light-dependent spores, LED grow lights with adjustable spectra can provide the necessary wavelengths without overheating. A timer ensures consistent exposure, typically 8–12 hours daily. For darkness-preferring spores, the focus shifts to eliminating light contamination. Using double-layered containers or storing cultures in windowless rooms minimizes accidental exposure. Additionally, monitoring temperature and humidity remains crucial, as these factors often interact with light conditions to influence germination success.

In essence, mastering spore germination hinges on respecting their light preferences. Whether harnessing light as a catalyst or shielding spores from it, the key lies in creating an environment that mimics their natural triggers. By tailoring light conditions to the specific needs of each species, cultivators can unlock the dormant potential of spores, fostering growth with precision and care.

Detecting Mold Spores in Air: Effective Testing Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Substrate Preparation: Use sterile, nutrient-rich substrates like agar or soil for successful germination

Sterilization is non-negotiable when preparing substrates for spore germination. Even a single contaminant can outcompete your spores, rendering your efforts futile. Autoclaving is the gold standard, using steam under pressure (15 psi at 121°C for 30 minutes) to eliminate bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms. For smaller batches, chemical sterilization with 70% ethanol or 10% bleach solutions can suffice, but these methods are less reliable and may leave residues harmful to spores. Always allow sterilized substrates to cool to room temperature before inoculation to prevent heat damage.

Nutrient composition is equally critical, as spores require a balanced mix of carbohydrates, amino acids, and vitamins to activate metabolic processes. Agar, a seaweed-derived gelatinous substance, is ideal for laboratory settings due to its clarity and ability to solidify at room temperature. For soil-based substrates, a mix of peat moss, vermiculite, and a small amount of lime-free sand provides aeration and moisture retention. Enriching soil with 0.5–1% glucose or malt extract can significantly enhance germination rates, though excessive nutrients may promote contamination.

The choice between agar and soil depends on your goals and environment. Agar is preferred for controlled experiments due to its sterility and uniformity, allowing precise observation of germination patterns. Soil, however, mimics natural conditions, making it suitable for mycorrhizal fungi or species adapted to terrestrial ecosystems. When using soil, ensure it is pasteurized (heated to 60°C for 30 minutes) to reduce microbial load without compromising its structure. For agar, adding activated carbon (0.1–0.2%) can inhibit bacterial growth while supporting fungal development.

Practical tips can streamline the process. Label all substrates with preparation dates and sterilization methods to avoid confusion. Store sterilized agar plates at 4°C for up to two weeks, but use soil substrates within 48 hours to prevent recontamination. When inoculating, use a flame-sterilized inoculation loop or needle to transfer spores, and work in a clean environment, such as a laminar flow hood or a DIY still-air box. Finally, monitor humidity levels around soil substrates; covering them with a breathable material like cheesecloth can maintain moisture without fostering mold growth.

Mastering substrate preparation is a blend of precision and adaptability. While agar offers consistency, soil provides ecological relevance. By prioritizing sterility, tailoring nutrient content, and employing practical techniques, you create an environment where spores thrive. Whether in a lab or garden, the right substrate is the foundation for successful germination, turning dormant spores into thriving mycelial networks.

Can Bacterial Spores Outlast Wildfires? Exploring Their Fire Survival Abilities

You may want to see also

Sterilization Techniques: Prevent contamination by sterilizing tools, containers, and substrates before use

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of successful spore germination, capable of derailing weeks of effort in an instant. Even a single stray bacterium or fungus can outcompete your spores for resources, rendering your substrate useless. Sterilization, therefore, isn't just a step—it's the foundation of your entire process. Every tool, container, and substrate must be treated as a potential threat until proven otherwise.

The Autoclave Advantage: For those with access to laboratory equipment, the autoclave reigns supreme. This pressurized steam chamber achieves temperatures of 121°C (250°F) for 15-30 minutes, effectively obliterating all microorganisms, including spore-forming bacteria. It's the gold standard for sterilizing substrates like agar, grain, and soil, ensuring a pristine environment for your spores. However, autoclaves are expensive and require proper training, making them less accessible for hobbyists.

Chemical Alternatives: When an autoclave isn't an option, chemical sterilization steps in. A 10% bleach solution (sodium hypochlorite) can be used to disinfect tools and glassware, followed by thorough rinsing with sterile water to remove residues. For substrates, a 70% isopropyl alcohol solution can be applied, but its effectiveness diminishes in the presence of organic matter. Remember, chemicals can leave harmful residues, so always prioritize thorough rinsing and drying.

Flame Sterilization: A Classic Technique: The simplicity of flame sterilization makes it a favorite for inoculation tools like needles and scalpels. Holding the metal portion of the tool in a bunsen burner flame until it glows red ensures all microorganisms are incinerated. This method is quick, effective, and requires minimal equipment, but demands caution to avoid burns and fires.

Dry Heat Sterilization: For heat-resistant materials like glass and metal, dry heat sterilization in an oven at 160°C (320°F) for 2 hours can be effective. This method is less reliable for substrates due to the uneven heat distribution and potential for scorching.

Choosing the Right Method: The best sterilization technique depends on your resources, the materials involved, and the level of sterility required. While autoclaving offers the highest assurance, it's not always feasible. Chemical and flame sterilization provide viable alternatives, but require careful execution to avoid contamination or damage. Remember, sterilization is not a one-time event; it's a mindset that permeates every step of the spore germination process.

How Spores Spread: Person-to-Person Transmission Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The best method to germinate spores is the PF Tek (Psilocybe Fanaticus Technique), which involves using a substrate like brown rice flour mixed with vermiculite, sterilizing it, and then inoculating it with spores in a sterile environment.

The ideal temperature for spore germination is between 75°F to 80°F (24°C to 27°C). This range promotes optimal growth without encouraging contamination.

Spores typically germinate within 3 to 14 days after inoculation, depending on the species, temperature, and environmental conditions.

Spores do not require light to germinate, but once mycelium develops, indirect light can help guide the growth of mushrooms.

To prevent contamination, sterilize all equipment, work in a clean environment, use a still air box or glove box, and avoid exposing the substrate to open air during inoculation.