Mycoremediation, the use of fungi to restore degraded environments, is an innovative and sustainable approach to addressing pollution and soil contamination. Growing mushrooms specifically for this purpose involves selecting the right species, such as oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) or shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*), which are known for their ability to break down toxins like hydrocarbons and heavy metals. The process begins with preparing a substrate, often contaminated soil or organic waste, which is inoculated with mushroom spawn. Maintaining optimal conditions—such as proper moisture, temperature, and aeration—is crucial for fungal growth and remediation effectiveness. As the mushrooms grow, they absorb and metabolize pollutants, transforming them into less harmful substances. This method not only cleanses the environment but also produces edible or medicinal mushrooms, making it a dual-purpose solution for ecological restoration and resource utilization.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mushroom Species | Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), Shiitake (Lentinula edodes), and Wine Cap Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata) are commonly used for mycoremediation due to their ability to degrade pollutants. |

| Substrate | Agricultural waste (straw, sawdust, corn cobs), contaminated soil, or lignocellulosic materials. Substrate should be pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competing organisms. |

| pH Level | Optimal pH range: 5.5–7.0. Adjust substrate pH using lime or sulfur to create a suitable environment for mushroom growth. |

| Moisture Content | Maintain 60–70% moisture in the substrate. Regular misting or watering is required to prevent drying. |

| Temperature | Ideal temperature range: 20–28°C (68–82°F) for most species. Avoid extreme temperatures to ensure healthy mycelium growth. |

| Humidity | High humidity (85–95%) is essential for fruiting. Use humidifiers or enclosed environments to maintain humidity levels. |

| Light | Indirect light is sufficient for mycelium growth. Direct sunlight can dry out the substrate. |

| Spawn Rate | Use 5–10% spawn (mushroom mycelium) by weight of the substrate for optimal colonization. |

| Colonization Time | 2–4 weeks, depending on species and environmental conditions. Monitor for full substrate colonization before fruiting. |

| Contaminant Types | Effective for remediating hydrocarbons (petroleum), heavy metals (lead, mercury), pesticides, and dyes. |

| Bioremediation Mechanism | Mushrooms secrete enzymes (e.g., laccases, peroxidases) that break down pollutants into less toxic compounds. |

| Harvesting | Harvest mushrooms when caps are fully open but before spores drop. Repeated fruiting cycles enhance remediation efficiency. |

| Safety Precautions | Wear protective gear when handling contaminated substrates. Ensure proper disposal of remediated materials. |

| Scalability | Suitable for small-scale (e.g., gardens) to large-scale (e.g., industrial sites) applications. |

| Cost | Low-cost compared to chemical or physical remediation methods, especially when using agricultural waste as substrate. |

| Regulations | Check local regulations for mycoremediation practices, especially for contaminated sites requiring permits. |

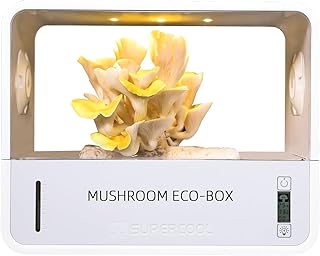

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

- Selecting suitable mushroom species for specific pollutants

- Preparing substrate with contaminated materials for fungal growth

- Optimizing environmental conditions for mycoremediation efficiency

- Monitoring mushroom growth and pollutant degradation over time

- Harvesting and disposing of mushrooms post-remediation safely

Selecting suitable mushroom species for specific pollutants

When selecting suitable mushroom species for mycoremediation, it is crucial to understand the specific pollutants you aim to target, as different fungi have varying abilities to degrade or accumulate particular contaminants. Mycoremediation leverages the natural metabolic processes of mushrooms to break down or absorb pollutants, making species selection a critical first step. For instance, *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom) is widely recognized for its ability to degrade petroleum hydrocarbons, making it an excellent choice for oil-contaminated sites. Similarly, *Trametes versicolor* (turkey tail) is effective against polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and certain pesticides, while *Ganoderma lucidum* (reishi) has shown potential in heavy metal accumulation. Researching the pollutant profile of your site will guide you in choosing the most effective species.

For heavy metal contamination, mushrooms with bioaccumulation capabilities are ideal. Species like *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) and *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane) are known to accumulate metals such as lead, cadmium, and mercury. However, it is essential to manage the disposal of these mushrooms carefully, as they can become toxic if consumed. In contrast, for organic pollutants like pesticides, herbicides, and industrial chemicals, white-rot fungi such as *Pleurotus* and *Trametes* species are highly effective due to their lignin-degrading enzymes, which can break down complex organic molecules. Understanding the pollutant type and the mushroom’s remediation mechanism ensures a targeted and efficient approach.

The environmental conditions of the remediation site also play a significant role in species selection. Some mushrooms thrive in specific pH levels, temperatures, and moisture conditions. For example, *Lentinula edodes* (shiitake) prefers a slightly acidic environment, while *Stropharia rugosoannulata* (wine cap) is more tolerant of a wider pH range. Additionally, consider the substrate on which the mushrooms will grow. Oyster mushrooms, for instance, grow well on straw and wood chips, making them suitable for sites with abundant agricultural waste. Matching the mushroom species to the site’s conditions maximizes their remediation potential.

Another factor to consider is the growth rate and colonization ability of the mushroom species. Fast-growing species like *Pleurotus ostreatus* can quickly cover large areas, making them ideal for rapid remediation projects. Slower-growing species, such as *Ganoderma lucidum*, may be more suitable for long-term, sustained remediation efforts. Additionally, some species, like *Mycelium* of *Stropharia rugosoannulata*, excel at colonizing disturbed soils, making them effective for stabilizing contaminated land while remediating it.

Lastly, consider the post-remediation management of the mushrooms. If the goal is to reuse the land for agriculture or other purposes, selecting edible or non-toxic species is advantageous. For example, *Pleurotus ostreatus* and *Lentinula edodes* are both edible and can be harvested for consumption or sale after remediation. However, if the mushrooms have accumulated heavy metals or toxic chemicals, they should be disposed of safely to prevent contamination of the food chain. Always consult local regulations and guidelines for the proper handling and disposal of mycoremediated materials.

In summary, selecting the right mushroom species for mycoremediation involves a detailed analysis of the pollutant type, environmental conditions, growth characteristics, and post-remediation management. By matching the species to the specific needs of the site, you can maximize the effectiveness of the remediation process and achieve sustainable results. Research and experimentation with different species may also uncover new applications for mycoremediation in various environmental contexts.

Shipping Mushroom Grow Kits to California: Legal Tips and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Preparing substrate with contaminated materials for fungal growth

Mycoremediation, the process of using fungi to degrade or sequester contaminants in the environment, begins with preparing a suitable substrate that both supports fungal growth and contains the contaminated materials. The substrate serves as the nutrient base for the mushrooms while exposing them to the pollutants they are intended to remediate. Here’s a detailed guide on preparing a substrate with contaminated materials for fungal growth.

First, identify the type of contamination you are addressing, as different fungi species have specific capabilities for breaking down particular pollutants, such as hydrocarbons, heavy metals, or pesticides. Once the contaminant is identified, select a fungal species known to remediate that specific pollutant. Common species used in mycoremediation include *Oyster mushrooms* (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), *Shiitake* (*Lentinula edodes*), and *Turkey Tail* (*Trametes versicolor*). The substrate should be composed of organic materials that the chosen fungus can easily colonize, such as straw, wood chips, sawdust, or agricultural waste. These materials provide the necessary carbon and nutrients for fungal growth.

Next, collect the contaminated material, ensuring it is safe to handle and does not pose health risks. The material should be finely ground or shredded to increase the surface area available for fungal interaction. Mix the contaminated material with the organic substrate in a ratio that allows the fungus to grow effectively while being exposed to the pollutant. A common ratio is 80% organic substrate to 20% contaminated material, but this may vary depending on the contaminant and fungal species. Sterilization or pasteurization of the substrate may be necessary to eliminate competing microorganisms that could hinder fungal colonization. This can be done by steaming, boiling, or using a pressure cooker, depending on the scale of the project.

After preparing the substrate, inoculate it with the chosen fungal species using spawn (fungal mycelium grown on a medium like grain). Mix the spawn thoroughly into the substrate to ensure even distribution. The inoculated substrate should then be placed in a clean, humid environment conducive to fungal growth, such as a plastic bag or tray with small holes for ventilation. Maintain optimal conditions for the fungus, including proper temperature, humidity, and light levels, as these vary by species.

Finally, monitor the substrate regularly for signs of fungal colonization, such as mycelium growth, and ensure it remains moist but not waterlogged. Over time, the fungus will begin to break down the contaminated material as part of its metabolic process. Regular testing of the substrate can help track the reduction of pollutants, ensuring the mycoremediation process is effective. Proper preparation of the substrate is critical to the success of mycoremediation, as it directly influences the fungus’s ability to grow and remediate contaminants.

Rapid Growth of Psychedelic Mushroom Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Optimizing environmental conditions for mycoremediation efficiency

Mycoremediation, the use of fungi to degrade or sequester environmental pollutants, relies heavily on optimizing environmental conditions to maximize the efficiency of mushroom growth and their pollutant-degrading capabilities. The first critical factor is substrate selection and preparation. Mushrooms used for mycoremediation, such as oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), thrive on lignocellulosic materials like straw, wood chips, or agricultural waste. The substrate should be pre-treated to enhance its bioavailability for fungal colonization. For instance, soaking wood chips in water or sterilizing the substrate can reduce competing microorganisms and create a favorable environment for mycelium growth. Additionally, enriching the substrate with nutrients like nitrogen can stimulate fungal activity, though care must be taken to avoid over-fertilization, which can inhibit mycoremediation efficiency.

Temperature and humidity control are equally vital for optimizing mycoremediation. Most mycoremediation fungi perform best in temperatures ranging from 20°C to 28°C (68°F to 82°F). Maintaining this range ensures rapid mycelial growth and enzymatic activity, which are essential for breaking down pollutants. Humidity levels should be kept consistently high, around 70-90%, to prevent desiccation of the mycelium and substrate. This can be achieved by misting the environment regularly or using humidifiers. Proper ventilation is also crucial to prevent the buildup of carbon dioxide, which can inhibit fungal growth, while ensuring adequate oxygen supply for aerobic degradation processes.

PH and moisture management play a significant role in mycoremediation efficiency. Fungi generally prefer slightly acidic to neutral pH levels, typically between 5.5 and 7.5. The substrate's pH can be adjusted using amendments like lime or sulfur to create an optimal environment for fungal activity. Moisture content must be carefully monitored; the substrate should be damp but not waterlogged, as excessive moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions and hinder mycelial growth. Regular monitoring with moisture meters and adjusting watering practices accordingly can help maintain the ideal balance.

Light and aeration are often overlooked but essential factors. While mushrooms do not require intense light for growth, indirect light can stimulate fruiting body formation, which is beneficial for certain mycoremediation strategies. Aeration is critical for maintaining oxygen levels necessary for fungal metabolism and pollutant degradation. This can be achieved by ensuring the substrate is not compacted and by periodically turning or agitating the material to introduce oxygen. In larger-scale applications, passive or active aeration systems can be employed to enhance oxygen availability.

Finally, monitoring and adjusting environmental conditions is key to sustained mycoremediation efficiency. Regularly testing the substrate for pH, moisture, and contaminant levels allows for timely adjustments to optimize fungal activity. Additionally, observing mycelial growth patterns and health indicators, such as color and density, can provide insights into the effectiveness of the remediation process. By maintaining a dynamic and responsive approach to environmental management, practitioners can ensure that mushrooms perform at their peak capacity for pollutant degradation.

Are Poisonous Mushrooms Common in Maryland? A Forager's Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Monitoring mushroom growth and pollutant degradation over time

To track pollutant degradation, collect soil or substrate samples at regular intervals (e.g., weekly or biweekly) and analyze them for target contaminants such as hydrocarbons, heavy metals, or pesticides. Techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) or atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) can provide precise measurements of pollutant levels. Compare these results to the baseline data to quantify the reduction in contaminants over time. Additionally, monitor environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity, and light exposure, as these factors influence both mushroom growth and remediation efficiency. Adjust conditions as needed to optimize fungal activity, ensuring the environment remains conducive to mycelium development.

Visual indicators of mushroom growth, such as fruiting bodies (the visible mushrooms), can also provide valuable insights. The presence of fruiting bodies typically signifies a mature and healthy mycelial network, though not all mycoremediation species will fruit under remediation conditions. Document the timing, size, and abundance of fruiting bodies, as these can correlate with the stage of pollutant degradation. However, the absence of fruiting bodies does not necessarily indicate failure, as mycelium can still actively remediate without producing mushrooms.

Incorporate biological assays to assess the toxicity of the substrate over time. For example, seed germination tests or bioassays using indicator organisms (e.g., *Daphnia* or *Vibrio fischeri*) can reveal changes in substrate toxicity as pollutants are degraded. These assays provide a functional measure of remediation progress, complementing chemical analyses. Maintain detailed records of all observations and test results, including photographs and notes on any anomalies or unexpected outcomes.

Finally, consider long-term monitoring to evaluate the sustainability of mycoremediation efforts. Even after pollutant levels have significantly decreased, continue periodic sampling to ensure contaminants do not reaccumulate and that the ecosystem remains healthy. Long-term monitoring also helps in understanding the resilience of the fungal species and their ability to persist in the environment, which is crucial for the lasting success of mycoremediation projects. By systematically tracking both mushroom growth and pollutant degradation, practitioners can refine their methods and maximize the effectiveness of this eco-friendly remediation technique.

Growing Button Mushrooms in Kenya: A Step-by-Step Guide to Success

You may want to see also

Harvesting and disposing of mushrooms post-remediation safely

Harvesting mushrooms post-remediation requires careful planning and execution to ensure both safety and effectiveness. Once the mycelium has completed its remediation work, typically indicated by the cessation of new growth or the stabilization of contaminant levels, it’s time to harvest the mushrooms. Wear protective gear, including gloves, a mask, and goggles, to avoid exposure to residual toxins or spores. Use clean, sterilized tools like knives or scissors to cut the mushrooms at the base, ensuring you don't damage the substrate or mycelium. Harvest only the mature mushrooms, leaving behind younger ones to continue growing if the remediation process is ongoing. Proper harvesting minimizes the risk of contaminant spread and ensures the mushrooms are safely removed for disposal.

After harvesting, the mushrooms must be disposed of safely to prevent the release of accumulated toxins or pathogens. Do not compost or discard them in regular waste, as this can reintroduce contaminants into the environment. Instead, place the harvested mushrooms in sealed, heavy-duty plastic bags to contain spores and toxins. Label the bags clearly with warnings about their contents and the type of contaminants they may hold. Contact local hazardous waste disposal facilities to inquire about proper disposal methods, as these mushrooms are often treated as contaminated material. Some regions may require specific protocols or accept them only at designated sites.

If you intend to test the mushrooms for contaminant levels, handle them with extra caution. Store them in airtight containers and send samples to a certified laboratory for analysis. This step is crucial to assess the success of the remediation process and ensure the mushrooms are safe for disposal. Avoid any contact with skin or inhalation of spores during this process, and clean all tools and surfaces thoroughly afterward. Proper documentation of test results can also be useful for future remediation projects or regulatory compliance.

In cases where mushrooms are grown in large-scale remediation projects, mechanical methods like vacuuming or HEPA-filtered equipment may be used to collect spores and mushroom fragments safely. This approach minimizes airborne contaminants and ensures a thorough cleanup. After collection, the substrate itself should be treated as contaminated material and disposed of according to local regulations. If the substrate is soil, it may need to be excavated and sent to a hazardous waste facility, depending on the severity of contamination.

Finally, educate yourself and any team members on post-remediation safety protocols. Wash all clothing and gear used during harvesting in hot water to remove any traces of contaminants. Monitor the remediation site for regrowth of mushrooms or signs of residual contamination. Proper documentation of the entire process, from harvesting to disposal, is essential for transparency and compliance with environmental regulations. By following these steps, you can ensure that the mycoremediation process is completed safely and effectively, protecting both human health and the environment.

Mastering Mushroom Cakes: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Success

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mycoremediation is the use of fungi, particularly mushrooms, to degrade or neutralize pollutants in the environment. Mushrooms secrete enzymes that break down toxins like hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and pesticides, converting them into less harmful substances.

Oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) and shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) are commonly used due to their ability to break down a wide range of pollutants. Other species like *Trametes versicolor* and *Ganoderma lucidum* are also effective for specific contaminants.

The substrate should be contaminated with the target pollutant but still provide nutrients for the mushrooms. Common substrates include straw, wood chips, or sawdust, which are sterilized or pasteurized before inoculating with mushroom spawn.

Yes, mycoremediation can be done indoors using controlled environments like grow tents or trays. Ensure proper ventilation, humidity, and temperature to support mushroom growth while addressing the contaminated material.

The time varies depending on the pollutant type, concentration, and mushroom species. It can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months. Regular monitoring of pollutant levels is essential to assess progress.