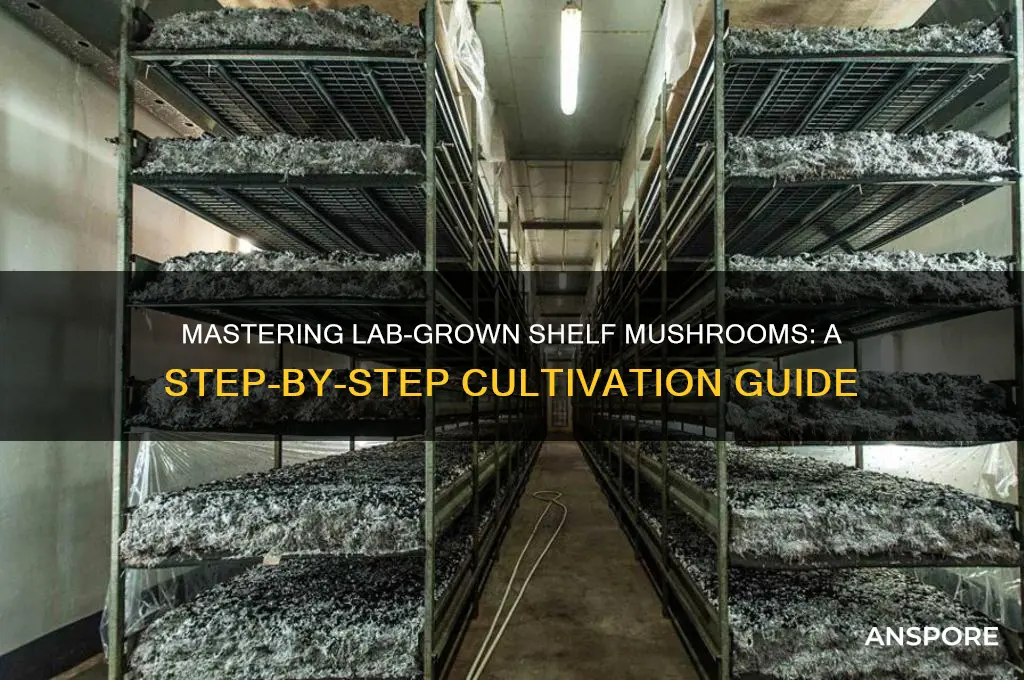

Growing shelf mushrooms in a lab setting requires a controlled environment to mimic their natural habitat, ensuring optimal conditions for mycelium development and fruiting. The process begins with selecting a suitable mushroom species, such as *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom), known for its adaptability and rapid growth. Sterilized substrates, typically composed of straw, sawdust, or agricultural waste, are inoculated with spawn, which introduces the mushroom’s mycelium. The substrate is then placed in a humid, temperature-regulated environment, usually between 20–25°C (68–77°F), with proper ventilation to prevent contamination. Light exposure, though not critical for mycelium growth, can stimulate fruiting body formation. Regular monitoring for mold or bacterial growth is essential, and the lab must maintain strict aseptic techniques throughout the process. With proper care, shelf mushrooms can be harvested within 2–4 weeks, offering a sustainable and efficient method for cultivation in a controlled setting.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mushroom Species | Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are most commonly grown due to fast growth and adaptability. |

| Substrate | Straw, sawdust, coffee grounds, or agricultural waste (sterilized or pasteurized). |

| Spawn | Grain spawn (e.g., rye, wheat) inoculated with mushroom mycelium. |

| Sterilization/Pasteurization | Substrate must be sterilized (autoclave at 121°C for 1-2 hours) or pasteurized (60-80°C for 1-2 hours) to kill contaminants. |

| Humidity | 85-95% relative humidity for optimal growth. |

| Temperature | 20-28°C (68-82°F) for incubation; 15-20°C (59-68°F) for fruiting. |

| Light | Indirect light (6-8 hours daily) triggers fruiting. |

| Air Exchange | Fresh air is essential; use a grow tent or room with ventilation. |

| pH Level | Substrate pH should be 5.5-6.5. |

| Incubation Time | 2-4 weeks for mycelium colonization. |

| Fruiting Time | 7-14 days after inducing fruiting conditions. |

| Harvesting | Mushrooms are ready when caps flatten or curl upward; twist and pull to harvest. |

| Contamination Prevention | Sterile techniques, HEPA filters, and clean lab environment. |

| Yield | 0.5-1 kg (1-2 lbs) per 5 kg (11 lbs) of substrate, depending on conditions. |

| Shelf Life | Fresh mushrooms last 5-7 days; dried mushrooms last 6-12 months. |

| Common Challenges | Contamination (mold, bacteria), improper humidity, or temperature fluctuations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sterilization Techniques: Autoclaving substrates, tools, and containers to eliminate contaminants for successful mushroom growth

- Spawn Preparation: Selecting and preparing mycelium spawn for inoculation into sterilized substrate

- Substrate Formulation: Mixing sawdust, grains, or straw with nutrients to create ideal growing medium

- Environmental Control: Maintaining humidity, temperature, and light conditions for optimal mushroom development

- Harvesting Process: Timing and techniques for picking mature mushrooms without damaging mycelium

Sterilization Techniques: Autoclaving substrates, tools, and containers to eliminate contaminants for successful mushroom growth

Sterilization is a critical step in cultivating shelf mushrooms in a lab setting, as it ensures that contaminants such as bacteria, fungi, and spores are eliminated, creating a clean environment for mycelium growth. Autoclaving is the most reliable method for sterilizing substrates, tools, and containers, as it uses high-pressure steam at 121°C (250°F) for 15–30 minutes to kill all microorganisms. Before autoclaving, prepare your substrate (e.g., sawdust, straw, or grain) by moistening it to the consistency of a wrung-out sponge and placing it in autoclavable bags. Seal the bags loosely to allow steam penetration, and ensure they are made of polypropylene or another heat-resistant material to withstand the autoclaving process.

When sterilizing tools such as scalpels, tweezers, and glassware, wrap them in aluminum foil or place them in heat-resistant containers to prevent damage. For containers like Petri dishes, jars, or grow bags, ensure they are empty and dry before autoclaving. Arrange items inside the autoclave in a way that allows steam to circulate freely, avoiding overcrowding. Run the autoclave cycle according to its specifications, typically at 15 psi for 30 minutes for most lab equipment and substrates. After the cycle, allow the autoclave to cool naturally to avoid contamination from external air.

For substrates, proper preparation is key to successful sterilization. If using sawdust or straw, supplement it with nutrients like wheat bran or gypsum, mix thoroughly, and moisten before bagging. Grain substrates, such as rye or millet, should be soaked, drained, and rinsed before autoclaving to remove inhibitors and ensure even moisture distribution. Once sterilized, allow substrates to cool to room temperature before inoculating with mushroom spawn to prevent heat damage to the mycelium.

It’s essential to verify autoclave effectiveness by using biological indicators, such as spore strips containing *Geobacillus stearothermophilus*, which confirm that the autoclave has reached the required temperature and pressure. Additionally, maintain a clean workspace and handle sterilized materials under a laminar flow hood or in a still-air box to minimize post-sterilization contamination. Regularly inspect and maintain your autoclave to ensure it functions correctly, as even minor malfunctions can compromise sterilization.

Finally, timing is crucial when working with sterilized materials. Inoculate substrates within 24 hours of autoclaving to reduce the risk of contamination. Store sterilized containers and tools in a clean, sealed environment until use. By mastering autoclaving techniques and adhering to strict sterilization protocols, you can create an optimal environment for shelf mushroom growth, maximizing yield and minimizing the risk of failed cultures.

Master Mushroom Cultivation: Growing on Straw Logs Step-by-Step

You may want to see also

Spawn Preparation: Selecting and preparing mycelium spawn for inoculation into sterilized substrate

Spawn preparation is a critical step in cultivating shelf mushrooms in a laboratory setting, as it directly influences the success of mycelial colonization and subsequent fruiting. The process begins with selecting a suitable mycelium strain, which should be robust, fast-growing, and known for its ability to fruit reliably. Common shelf mushroom species like *Lentinula edodes* (shiitake) or *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom) are popular choices. Ensure the mycelium culture is obtained from a reputable supplier or sourced from a healthy, contaminant-free mother culture. Contaminated spawn can lead to failed crops, so visual inspection for molds, bacteria, or other abnormalities is essential before proceeding.

Once a healthy mycelium strain is selected, the next step is preparing the spawn medium. Grain spawn is the most commonly used type due to its ease of sterilization and ability to support vigorous mycelial growth. Typically, grains like rye, wheat, or millet are used. The grains must be cleaned thoroughly to remove dust and debris, then soaked in water for 12–24 hours to hydrate them. After soaking, the grains are drained and placed in jars or bags, leaving enough headspace for expansion during sterilization. Sterilization is crucial to eliminate competing microorganisms; this is achieved using an autoclave at 121°C (250°F) for 60–90 minutes. Properly sterilized grains should appear moist but not waterlogged.

After sterilization, the grains must cool to a temperature that will not kill the mycelium (around 25–30°C or 77–86°F) before inoculation. Inoculating the grain spawn involves transferring a small amount of healthy mycelium culture to the sterilized grains under sterile conditions. This is typically done in a laminar flow hood or a still-air box to minimize contamination. Using a sterile tool, such as a scalpel or inoculation loop, introduce a few pieces of actively growing mycelium into the grain substrate. Seal the jars or bags with a filter patch to allow gas exchange while preventing contaminants from entering.

Following inoculation, the spawn jars are placed in a warm, dark environment (22–28°C or 72–82°F) to encourage mycelial growth. Monitoring the spawn during incubation is vital; the mycelium should colonize the grains within 2–3 weeks, depending on the strain and conditions. Fully colonized spawn appears uniformly white and dense, with no signs of contamination. If mold or unusual colors appear, the spawn should be discarded to prevent contamination of the substrate.

Finally, the prepared spawn is ready for inoculation into the sterilized substrate. Ensure the substrate is cooled to a safe temperature before introducing the spawn to avoid damaging the mycelium. Mix the spawn thoroughly but gently into the substrate, maintaining sterile conditions throughout the process. Properly prepared spawn will rapidly colonize the substrate, setting the stage for healthy mushroom fruiting. Attention to detail during spawn preparation is key to achieving consistent and successful shelf mushroom cultivation in a laboratory environment.

Discovering Chanterelle Mushrooms: Ideal Habitats and Growing Conditions Explained

You may want to see also

Substrate Formulation: Mixing sawdust, grains, or straw with nutrients to create ideal growing medium

Substrate formulation is a critical step in growing shelf mushrooms in a lab setting, as it directly influences mycelium colonization and fruiting body development. The substrate serves as both a physical support and a nutrient source for the mushrooms. To create an ideal growing medium, start by selecting a base material such as sawdust, grains, or straw, each offering unique advantages. Sawdust, particularly from hardwoods like oak or beech, is widely used due to its high lignin and cellulose content, which mushrooms efficiently break down. Grains like rye or wheat provide faster colonization due to their rich carbohydrate profile, while straw (e.g., wheat or rice) is cost-effective and readily available, though it may require supplementation for optimal nutrition.

Once the base material is chosen, it must be mixed with nutrients to create a balanced substrate. A common approach is to combine the base with a nutrient supplement, such as bran, soybean meal, or cottonseed meal, which provide essential proteins and minerals. For example, a typical sawdust-based substrate might include 70-80% sawdust and 20-30% bran or soybean meal. For grain-based substrates, the grains are often pre-pasteurized or sterilized before mixing with supplements to prevent contamination. Straw-based substrates benefit from the addition of gypsum (calcium sulfate) to improve water retention and provide calcium, a crucial element for mushroom growth.

Moisture content is another critical factor in substrate formulation. The mixture should be damp but not waterlogged, typically achieving a moisture level of 60-70%. This can be tested by squeezing a handful of the substrate—it should release a few drops of water but not leave your hand wet. Adjust moisture by adding water gradually during mixing. Proper hydration ensures the mycelium can efficiently colonize the substrate while preventing anaerobic conditions that could lead to contamination.

Sterilization or pasteurization of the substrate is essential to eliminate competing microorganisms. For lab settings, sterilization is often preferred, involving the use of an autoclave to treat the substrate at 121°C (250°F) for 1-2 hours. Pasteurization, which uses lower temperatures (60-80°C or 140-176°F), is less harsh but may not eliminate all contaminants. After sterilization or pasteurization, allow the substrate to cool to around 25-30°C (77-86°F) before inoculating with mushroom spawn to avoid damaging the mycelium.

Finally, the substrate should be packed into growing containers, such as polypropylene bags or trays, with small holes for gas exchange. The density of packing depends on the mushroom species; for shelf mushrooms like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms), a loose to medium pack works best to allow fruiting bodies to develop. Properly formulated and prepared substrate sets the foundation for successful mushroom cultivation, ensuring robust mycelium growth and abundant fruiting in the controlled environment of a lab.

Do Morel Mushrooms Grow at Night? Unveiling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.49 $29.99

Environmental Control: Maintaining humidity, temperature, and light conditions for optimal mushroom development

Growing shelf mushrooms in a lab setting requires precise environmental control to mimic their natural habitat and ensure optimal development. Humidity is one of the most critical factors, as mushrooms thrive in high-moisture environments. The ideal relative humidity for shelf mushrooms typically ranges between 85% and 95%. To maintain this, use a humidifier or misting system to regularly add moisture to the air. Additionally, ensure proper ventilation to prevent stagnant air, which can lead to mold or bacterial growth. Substrates should also be kept moist but not waterlogged, as excessive water can suffocate the mycelium. Regularly monitor humidity levels using a hygrometer and adjust the misting frequency or ventilation accordingly.

Temperature control is equally vital for successful mushroom cultivation. Shelf mushrooms generally grow best in temperatures ranging from 65°F to 75°F (18°C to 24°C). Fluctuations outside this range can slow growth or even kill the mycelium. Use heating or cooling systems, such as thermostatically controlled incubators or grow rooms, to maintain a stable temperature. Insulation and thermal curtains can help regulate temperature in larger setups. Monitor temperature continuously with a digital thermometer and make adjustments as needed to ensure consistency. During the fruiting stage, a slight drop in temperature (around 5°F or 3°C) can often stimulate mushroom formation.

Light conditions play a subtle but important role in mushroom development. Unlike plants, mushrooms do not require intense light for photosynthesis, but they do need some light to trigger fruiting. Indirect, diffused light is ideal, mimicking the dappled light of a forest floor. Provide 8–12 hours of low-intensity light daily using LED or fluorescent bulbs. Avoid direct sunlight, as it can dry out the substrate and stress the mushrooms. Darkness is also necessary for mycelium growth during the initial colonization phase, so consider using a timer to automate light cycles.

Maintaining the right balance between humidity, temperature, and light requires consistent monitoring and adjustments. Use environmental sensors and automated systems where possible to reduce human error and ensure stability. Regularly inspect the growing area for signs of contamination or stress, such as discoloration or slow growth, and address issues promptly. Proper environmental control not only maximizes yield but also ensures the health and quality of the mushrooms produced. By creating a stable and controlled environment, you can replicate the conditions shelf mushrooms need to flourish in a lab setting.

Optimal Conditions for Morel Mushrooms: Habitat, Soil, and Climate Secrets

You may want to see also

Harvesting Process: Timing and techniques for picking mature mushrooms without damaging mycelium

Harvesting shelf mushrooms in a lab setting requires careful timing and precise techniques to ensure the mushrooms are picked at peak maturity while preserving the mycelium for future flushes. The ideal time to harvest is when the caps of the mushrooms have fully expanded but before the gills begin to drop spores. This stage is typically reached 5-7 days after the mushrooms first appear, depending on the species and growing conditions. Observing the mushrooms daily is crucial; look for signs such as caps flattening out or slightly curling upward, which indicate maturity. Harvesting too early results in underdeveloped mushrooms, while waiting too long allows spores to drop, reducing shelf life and potentially contaminating the growing environment.

To harvest without damaging the mycelium, use a clean, sharp knife or scalpel to cut the mushroom at the base of the stem. Avoid pulling or twisting the mushroom, as this can disturb the mycelium and reduce future yields. Hold the mushroom gently with one hand and carefully slice it off, ensuring a clean break from the substrate. Leave a small portion of the stem attached to the growing medium to minimize injury to the mycelial network. Work methodically, harvesting the largest, most mature mushrooms first to allow smaller ones more time to develop.

After harvesting, inspect the growing area for any signs of contamination or damage to the mycelium. Remove any debris or decaying mushrooms that could introduce pathogens. Properly cleaning your tools with alcohol or a sterilizing solution between cuts is essential to prevent the spread of contaminants. If multiple mushrooms are ready for harvest, work in a pattern across the growing surface to avoid concentrating pressure or damage in one area.

Post-harvest, the substrate should be misted lightly to maintain humidity and encourage the next flush of mushrooms. Avoid overwatering, as excess moisture can lead to mold or other issues. Monitor the mycelium for signs of new pinhead formation, which typically appears within 5-10 days after the first harvest. With proper care, shelf mushrooms can produce multiple flushes, making the preservation of the mycelium during harvesting critical for long-term success.

Finally, store the harvested mushrooms properly to maintain their quality. Place them in a breathable container, such as a paper bag or loosely covered with a damp cloth, and refrigerate immediately. Shelf mushrooms can last up to a week when stored correctly, but they are best used within a few days for optimal flavor and texture. By mastering the timing and techniques of harvesting, you can maximize yields while ensuring the health and productivity of the mycelium in your lab-grown mushroom cultivation.

Exploring Porcini Mushrooms: Natural Habitats and Ideal Growing Conditions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Shelf mushrooms (like oyster mushrooms) require a controlled environment with specific conditions: a temperature range of 65–75°F (18–24°C), humidity levels of 60–80%, and proper ventilation. Additionally, a sterile substrate (e.g., straw, sawdust, or coffee grounds) and mushroom spawn are necessary for successful growth.

Sterilize the substrate by steaming it at 176°F (80°C) for 1–2 hours or using a pressure cooker at 15 psi for 1.5 hours. This kills contaminants and prepares the substrate for inoculation with mushroom spawn.

Mix the mushroom spawn evenly into the sterilized and cooled substrate, ensuring thorough distribution. Place the mixture into sterile containers or bags, seal them, and incubate in a dark, warm area (65–75°F) for 2–4 weeks until fully colonized.

After full colonization, expose the mycelium to cooler temperatures (55–65°F or 13–18°C), high humidity (85–95%), and indirect light. Introduce fresh air exchange to trigger pinhead formation and fruiting body development. Maintain these conditions until mushrooms mature.