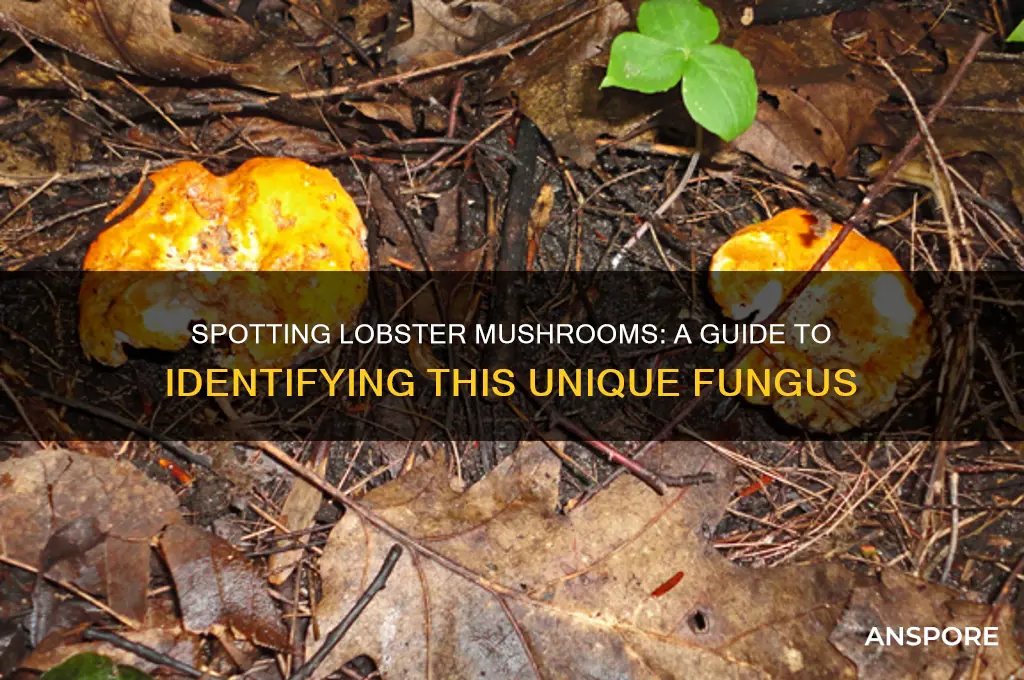

The lobster mushroom, despite its name, is not a mushroom but rather a unique culinary creation resulting from a parasitic relationship between a fungus (Hypomyces lactifluorum) and a host mushroom, typically the Russulaceae family. Identifying a lobster mushroom involves recognizing its distinctive appearance: it has a vibrant reddish-orange exterior resembling the shell of a cooked lobster, hence its name. The interior is usually white to pale orange, and the texture is firm and meaty. Unlike many other mushrooms, the lobster mushroom lacks gills, instead featuring a smooth or slightly wrinkled surface. Its size can vary, but it often grows to be several inches tall. Foraging enthusiasts should also note its strong, seafood-like aroma, which is a key characteristic. Proper identification is crucial, as some mushrooms can be toxic, but the lobster mushroom is not only safe to eat but also highly prized for its flavor and texture.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Hypomyces lactifluorum |

| Common Name | Lobster Mushroom |

| Color | Bright orange to reddish-orange, resembling a cooked lobster |

| Shape | Irregular, lumpy, or lobed, often deforming the host mushroom |

| Texture | Firm, chewy, and meaty when cooked |

| Host Mushroom | Typically Lactarius or Russula species |

| Size | 5–20 cm (2–8 inches) in diameter |

| Gill/Pore Structure | Host mushroom's gills or pores are usually obscured by the parasitic mold |

| Spore Color | White to pale yellow (from the Hypomyces mold) |

| Smell | Mild, seafood-like aroma |

| Taste | Mild, slightly nutty or seafood-like when cooked |

| Habitat | Coniferous and deciduous forests, often under trees |

| Season | Late summer to fall |

| Edibility | Edible and prized when properly prepared (host mushroom is inedible alone) |

| Key Identifier | Bright orange color and parasitic growth on Lactarius or Russula |

| Look-Alikes | Avoid confusing with toxic orange fungi like Omphalotus olearius |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Color and Texture: Look for reddish-orange, wrinkled, lobster shell-like appearance with a firm, meaty texture

- Host Mushroom: Typically grows on Russula or Lactarius mushrooms, distorting their shape

- Aroma: Mild, seafood-like scent, distinct from typical mushroom odors

- Parasitic Nature: Caused by *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, a fungus that infects other mushrooms

- Habitat: Found in coniferous or deciduous forests, often under trees, in late summer/fall

Color and Texture: Look for reddish-orange, wrinkled, lobster shell-like appearance with a firm, meaty texture

When identifying a lobster mushroom, color is one of the most striking features to look for. The cap and stem of a mature lobster mushroom typically exhibit a vibrant reddish-orange hue, reminiscent of cooked lobster meat. This color is a result of a parasitic fungus, *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, colonizing a host mushroom, usually a species from the *Lactarius* or *Russula* genus. The intensity of the reddish-orange color can vary, but it should be consistent and evenly distributed across the mushroom's surface. If you notice patches of white or other colors, it may indicate an immature specimen or a different species altogether.

The texture of a lobster mushroom is equally distinctive. Its surface is characterized by a wrinkled, lobster shell-like appearance, which adds to its unique visual appeal. These wrinkles are not smooth but rather have a slightly rough, bumpy texture that mimics the exterior of a lobster shell. When you handle the mushroom, you’ll notice its firm, meaty texture, which sets it apart from many other fungi. Unlike delicate or spongy mushrooms, the lobster mushroom feels dense and substantial, almost like a piece of cooked seafood. This texture is a key identifier and should feel consistent throughout the cap and stem.

To further assess the texture, gently press the mushroom’s surface. A lobster mushroom should yield slightly under pressure but quickly bounce back, indicating its firmness. Avoid specimens that feel soft, mushy, or hollow, as these may be overripe or affected by decay. The wrinkled appearance is not just a visual cue but also a tactile one—run your fingers over the surface to confirm the presence of these characteristic ridges. This combination of color and texture makes the lobster mushroom one of the most recognizable fungi in the wild.

When examining the mushroom’s reddish-orange color, pay attention to its uniformity. The shade should be consistent, though it may deepen or lighten slightly in certain areas. The wrinkled texture should be present across the entire cap and often extends down the stem, though it may be less pronounced there. The firm, meaty texture is particularly important, as it distinguishes the lobster mushroom from its host, which is typically brittle or spongy in comparison. If the mushroom feels too hard or too soft, it may not be a true lobster mushroom.

Finally, the lobster shell-like appearance is a defining trait. Imagine the uneven, ridged surface of a lobster’s exoskeleton, and you’ll have a good mental image of what to look for. This texture is not just superficial but is a result of the parasitic fungus transforming the host mushroom’s structure. Combined with the reddish-orange color and firm texture, these features make the lobster mushroom unmistakable. Always remember to cross-reference these characteristics with other identification guides to ensure accuracy, as misidentification can lead to unsafe foraging.

Psychedelic Mushroom Spores: Are They Illegal?

You may want to see also

Host Mushroom: Typically grows on Russula or Lactarius mushrooms, distorting their shape

The lobster mushroom, despite its seafood-inspired name, is not a mushroom that grows in the ocean. Instead, it is a unique culinary delight formed through a fascinating parasitic relationship. The star of this relationship is the *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, a fungus that specifically targets two genera of mushrooms: Russula and Lactarius. These host mushrooms are commonly found in forests across North America, Europe, and Asia, and they serve as the foundation for the lobster mushroom's distinctive appearance and texture. When identifying a lobster mushroom, it's crucial to recognize the presence of its host, as the *Hypomyces lactifluorum* completely envelops and transforms the original mushroom, distorting its shape and altering its color.

Russula and Lactarius mushrooms are typically characterized by their brittle flesh and distinct cap and stem structure. Russula mushrooms often have brightly colored caps and are known for their spicy or acrid taste, while Lactarius mushrooms are recognized by their milky latex-like substance that exudes when the flesh is damaged. However, when these mushrooms become hosts to *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, their original features are dramatically altered. The parasitic fungus grows over the host, creating a thick, crust-like layer that resembles the texture of lobster shell, hence the name "lobster mushroom." This transformation results in a distorted shape, where the original cap and stem of the host mushroom may become misshapen or entirely obscured.

To identify a lobster mushroom, look for signs of the host mushroom's original structure beneath the parasitic layer. The distorted shape is a key indicator, as the *Hypomyces lactifluorum* does not grow independently but relies on the host for its structure. The lobster mushroom typically retains the general form of the host, but with a noticeably warped or lumpy appearance. The host's gills or pores are usually covered by the parasitic fungus, which forms a dense, reddish-orange to brownish exterior. This color is another distinguishing feature, as it contrasts sharply with the typical hues of Russula and Lactarius mushrooms.

When examining a potential lobster mushroom, consider the habitat where it was found. Russula and Lactarius mushrooms are often found in coniferous or deciduous forests, particularly under trees like pine, oak, or birch. The presence of these trees can be a clue that you are in an area where the host mushrooms, and consequently lobster mushrooms, are likely to grow. Additionally, the season plays a role, as lobster mushrooms are most commonly found in late summer to early fall, coinciding with the fruiting season of their host mushrooms.

In summary, identifying a lobster mushroom hinges on recognizing the distorted shape of its Russula or Lactarius host, which is enveloped by the *Hypomyces lactifluorum*. The parasitic fungus transforms the host's appearance, creating a unique, crust-like exterior that mimics the texture of lobster shell. By focusing on the distorted shape, the reddish-orange to brownish color, and the typical habitats of the host mushrooms, foragers can confidently distinguish lobster mushrooms from other forest fungi. This knowledge not only aids in identification but also ensures a safe and rewarding foraging experience.

Mastering Stuffed Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide to Prepping Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Aroma: Mild, seafood-like scent, distinct from typical mushroom odors

When identifying a lobster mushroom, one of the most distinctive features to pay attention to is its aroma. Unlike the earthy, woody, or nutty scents commonly associated with mushrooms, the lobster mushroom emits a mild, seafood-like scent that is immediately recognizable. This unique fragrance is often described as reminiscent of cooked lobster or shellfish, which is fitting given its name. To detect this aroma, gently crush or break a small piece of the mushroom and bring it close to your nose. The scent should be subtle yet unmistakable, setting it apart from other fungi in the forest.

The seafood-like scent of the lobster mushroom is a result of a parasitic relationship between a fungus (*Hypomyces lactifluorum*) and a host mushroom (typically *Lactarius* or *Russula* species). This interaction alters not only the appearance but also the chemical composition of the mushroom, contributing to its distinct aroma. When foraging, this characteristic can be a valuable clue, especially in dense woodland areas where visual identification alone might be challenging. The aroma is not overpowering but rather a delicate hint of the sea, making it a key sensory marker.

To ensure you’re correctly identifying the aroma, compare it with the typical smells of other mushrooms you encounter. Common mushrooms often have earthy, musky, or even pungent odors, whereas the lobster mushroom’s scent is distinctly different. It lacks the forest floor notes and instead carries a light, briny quality. This contrast is crucial for accurate identification, as it helps rule out similar-looking species that lack this unique fragrance.

When examining the aroma, it’s also important to note that the intensity can vary slightly depending on the mushroom’s age and environmental conditions. Younger specimens may have a fresher, more pronounced seafood scent, while older ones might be milder. Regardless, the mild, seafood-like quality remains consistent. If the aroma is absent or resembles that of a typical mushroom, it’s likely not a lobster mushroom.

Finally, while the aroma is a critical identifier, it should always be used in conjunction with other characteristics such as appearance, texture, and habitat. The lobster mushroom’s reddish-orange color, firm yet pliable flesh, and woodland habitat are equally important. However, the distinct seafood-like scent remains one of the most reliable and memorable features for foragers. By focusing on this aroma, you can confidently distinguish the lobster mushroom from its forest counterparts.

False Pheasant Back Mushroom: Myth or Misidentification Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

Parasitic Nature: Caused by *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, a fungus that infects other mushrooms

The lobster mushroom, despite its seafood-inspired name, is not a mushroom in the conventional sense but rather a dramatic transformation of other fungi by the parasitic fungus *Hypomyces lactifluorum*. This unique relationship begins when the spores of *Hypomyces lactifluorum* land on a suitable host mushroom, typically species from the *Lactarius* or *Russula* genera. Once the spores germinate, the parasite begins to grow hyphae—thread-like structures—that penetrate the host’s tissues. This invasion is not merely superficial; *Hypomyces lactifluorum* takes over the host’s cells, redirecting its resources to fuel its own growth and reproduction. This parasitic takeover is the first key to identifying a lobster mushroom: it is always the result of this specific fungal infection.

As *Hypomyces lactifluorum* colonizes its host, it alters the mushroom’s appearance, texture, and even chemical composition. The once soft, often brittle flesh of the host becomes firm and meaty, resembling the texture of cooked lobster—hence the name. The parasite also imparts a striking reddish-orange to rust-brown color, which contrasts sharply with the host’s original hues. This transformation is so complete that the original features of the host mushroom are often obscured, making it difficult to identify the species that was initially infected. However, this dramatic change in color and texture is a telltale sign of the parasitic nature of *Hypomyces lactifluorum* and a primary characteristic to look for when identifying a lobster mushroom.

The parasitic relationship between *Hypomyces lactifluorum* and its host is not just physical but also biochemical. The parasite produces compounds that not only alter the host’s structure but also enhance its own survival. For instance, *Hypomyces lactifluorum* synthesizes pigments that give the lobster mushroom its distinctive color, which may serve to attract insects for spore dispersal. Additionally, the parasite breaks down the host’s tissues, converting them into nutrients that sustain its growth. This process is so efficient that the host mushroom essentially becomes a vessel for the parasite’s life cycle. When identifying a lobster mushroom, understanding this biochemical takeover helps explain why the mushroom’s original characteristics are so thoroughly masked.

Another critical aspect of the parasitic nature of *Hypomyces lactifluorum* is its specificity and consistency. While it primarily infects *Lactarius* and *Russula* species, the resulting lobster mushroom retains a predictable set of features regardless of the host. For example, the infected mushroom will always have a firm, lobster-like texture and a reddish-orange to brown color. The cap and stem may appear distorted or elongated compared to the original host, but the overall structure remains mushroom-like. This consistency in transformation is a direct result of the parasite’s uniform effect on its hosts and is a key identifier when distinguishing a lobster mushroom from other fungi.

Finally, the parasitic nature of *Hypomyces lactifluorum* also influences the lobster mushroom’s habitat and seasonality. Since the parasite relies on specific host mushrooms, lobster mushrooms are typically found in the same environments as *Lactarius* and *Russula* species—often coniferous or mixed woodlands. They are most commonly encountered in late summer to fall, coinciding with the fruiting season of their hosts. When searching for lobster mushrooms, knowing the ecology of their hosts and the timing of their appearance can further confirm their identity. This parasitic relationship, therefore, not only shapes the lobster mushroom’s physical characteristics but also dictates where and when it can be found.

Kettle & Fire Mushroom Chicken Bone Broth: Nutrition, Benefits, and Taste Review

You may want to see also

Habitat: Found in coniferous or deciduous forests, often under trees, in late summer/fall

The lobster mushroom, a unique and sought-after fungus, thrives in specific environments that are crucial for its identification. Its habitat is primarily coniferous or deciduous forests, where the interplay of trees and soil creates the ideal conditions for its growth. These forests provide the necessary shade, humidity, and organic matter that the lobster mushroom relies on. When foraging, focus your search in wooded areas dominated by trees like pines, spruces, or hardwoods such as oaks and maples. The forest floor, rich in decaying leaves and wood, acts as a nutrient base for this parasitic fungus.

Lobster mushrooms are often found under trees, particularly where the soil is moist and well-drained. They form a symbiotic relationship with their host mushrooms, typically species from the *Lactarius* or *Russula* genera, which are commonly found near tree roots. Look for them in areas with dense tree cover, as the shade helps maintain the cool, damp conditions they prefer. Fallen logs, tree stumps, and mossy patches are also prime locations, as they provide additional organic material and moisture.

The timing of your search is just as important as the location. Lobster mushrooms are most commonly found in late summer to fall, coinciding with the fruiting season of their host mushrooms. This period typically spans from August to October, depending on your geographic location and local climate. Cooler temperatures and increased rainfall during this time stimulate their growth, making them more visible on the forest floor.

To maximize your chances of finding lobster mushrooms, focus on forests with a mix of coniferous and deciduous trees, as these environments offer diverse habitats for their hosts. Walk slowly and scan the ground carefully, as their reddish-orange color can blend with fallen leaves or pine needles. Remember, their presence is closely tied to the availability of their host mushrooms, so areas with abundant *Lactarius* or *Russula* species are particularly promising.

Lastly, while exploring these habitats, be mindful of the ecosystem. Avoid disturbing the forest floor unnecessarily, and always follow local foraging regulations. By understanding and respecting their habitat, you’ll not only increase your chances of identifying lobster mushrooms but also contribute to their conservation in the wild.

Mushroom vs Yeast: What's the Difference?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A lobster mushroom is not a single species but a parasitic fungus (*Hypomyces lactifluorum*) that infects certain mushrooms, typically from the *Lactarius* or *Russula* genera. It transforms the host mushroom, giving it a reddish-orange color, firm texture, and seafood-like flavor, resembling cooked lobster.

Look for a reddish-orange to brownish exterior with a firm, dense texture. The mushroom often retains the shape of its host (e.g., *Lactarius* or *Russula*), but the surface will be wrinkled or lobed. The gills of the host are usually obscured by the parasitic fungus.

Yes, lobster mushrooms are edible and highly prized for their unique flavor. However, proper identification is crucial, as the host mushroom alone may be inedible or toxic. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert, and ensure the mushroom has the characteristic reddish-orange color, firm texture, and parasitic growth pattern.