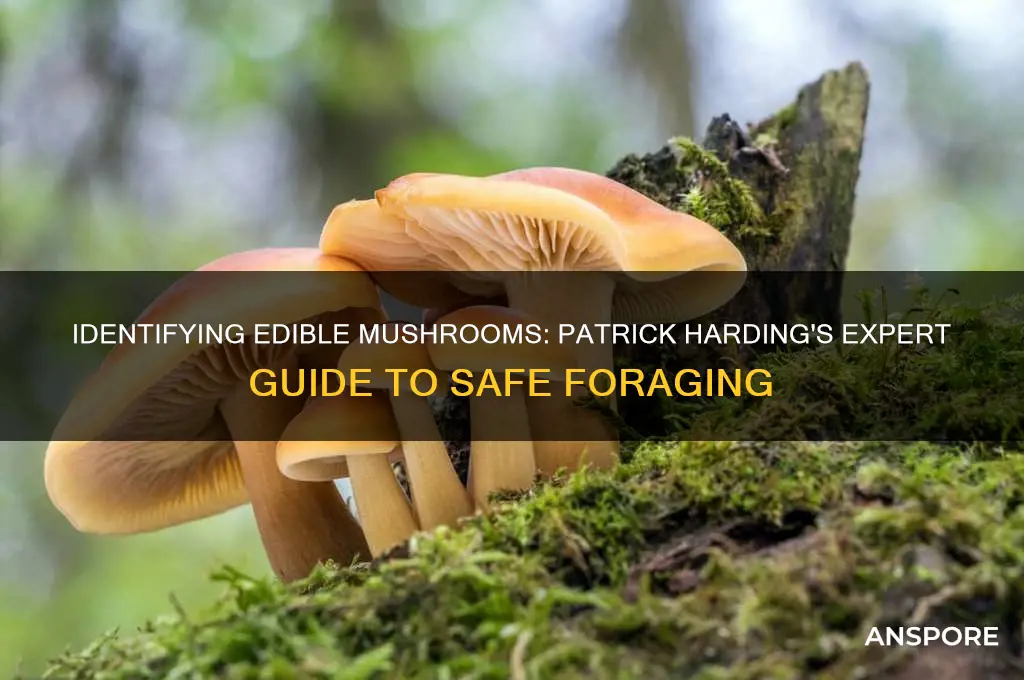

Identifying edible mushrooms is a skill that requires knowledge, caution, and practice, and Patrick Harding, a renowned mycologist and foraging expert, offers invaluable insights into this fascinating yet potentially dangerous endeavor. With a deep understanding of fungal ecology and taxonomy, Harding emphasizes the importance of accurately identifying species to avoid toxic look-alikes. His teachings focus on key characteristics such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat, while also highlighting the risks of relying solely on folklore or superficial traits. By following Harding’s meticulous approach, enthusiasts can safely distinguish edible varieties like chanterelles or porcini from poisonous imposters, ensuring a rewarding and secure foraging experience.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Spore print color identification

Spore print color is a critical characteristic for identifying mushrooms, offering a reliable clue to their species. To create a spore print, place the cap of a mature mushroom gill-side down on a piece of paper or glass, cover it with a bowl to maintain humidity, and leave it undisturbed for 24 hours. The spores will drop onto the surface, revealing their color. This method is particularly useful because spore color is consistent within species, unlike cap color, which can vary due to environmental factors. For instance, the spore print of the edible *Lactarius deliciosus* is a distinctive orange-red, while the deadly *Amanita phalloides* produces a white spore print.

Analyzing spore print color requires attention to detail and the right tools. Use white and black paper to contrast with light and dark spores, ensuring accurate observation. For example, the spores of *Coprinus comatus*, the shaggy mane mushroom, appear black on white paper but may blend into black paper, making white the better choice. Conversely, the rusty brown spores of *Boletus edulis* are more visible on black paper. Always handle mushrooms with clean hands or gloves to avoid contaminating the print, which could lead to misidentification.

While spore print color is a valuable tool, it is not foolproof and should be used in conjunction with other identification methods. For instance, some mushrooms have spores that are too fine or sparse to produce a clear print, such as those in the *Marasmius* genus. Additionally, certain species may have spore colors that overlap, like the white spores of both edible *Agaricus bisporus* and toxic *Amanita ocreata*. Therefore, rely on spore print color as one piece of the puzzle, alongside characteristics like gill attachment, cap texture, and habitat.

Practical tips can enhance your success in spore print identification. Work with fresh, mature specimens, as immature or overripe mushrooms may not release spores effectively. If the mushroom has a partial veil or volva, remove it before placing the cap on the paper to avoid obstruction. For small or delicate mushrooms, use a razor blade to carefully separate the cap from the stem. Finally, document your findings with photographs or notes, including the time and conditions under which the print was made, to build a reliable reference for future identifications.

In conclusion, spore print color identification is a precise and revealing technique for mushroom enthusiasts. By mastering this method, you gain a deeper understanding of fungal taxonomy and improve your ability to distinguish edible species from toxic look-alikes. Remember, while spore color is a powerful identifier, it should always be cross-referenced with other features to ensure accuracy. With practice and patience, spore printing becomes an indispensable skill in your mycological toolkit.

Can You Eat Mushrooms Grown in Cow Manure? Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Gill attachment and structure analysis

The gills of a mushroom are its reproductive organs, and their attachment to the stem can reveal crucial details about the species. Free gills, for example, are not attached to the stem and can be a hallmark of certain edible varieties like the Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus). Conversely, adnate gills, which attach broadly to the stem, are common in many Lactarius species, some of which are edible but require careful identification due to look-alikes. Understanding these attachments is the first step in narrowing down your mushroom’s identity.

Next, examine the gill structure itself. Gills can be distant, close, or crowded, and their spacing often correlates with the mushroom’s age and habitat. For instance, the gills of young Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius) are often distant and fork-like, becoming more crowded as the mushroom matures. A hand lens can help you observe finer details, such as whether the gills are serrated or smooth, which can differentiate between similar species. For example, the serrated gills of the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius) are a warning sign, as this toxic look-alike mimics the edible Chantrelle.

When analyzing gill attachment and structure, consider the mushroom’s overall context. A mushroom with free gills growing in a grassy field might be a Shaggy Mane, but the same gill type in a woodland setting could indicate a different species. Always cross-reference gill characteristics with other features like cap color, spore print, and habitat. For beginners, practice on known species before attempting identification in the wild. A spore print kit, available for $10–$20, can complement gill analysis by revealing spore color, another critical identification factor.

One practical tip is to document your findings with photographs and notes. For instance, if you observe adnate gills with a pinkish hue, note the mushroom’s location, time of year, and nearby trees. This data can later be compared with field guides or apps like iNaturalist for verification. Remember, gill analysis is not foolproof; some toxic mushrooms, like the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata), have gills that mimic edible species. Always consult multiple resources and, when in doubt, avoid consumption.

Finally, consider the ethical and safety implications of your analysis. Overharvesting or misidentification can harm both ecosystems and individuals. If you’re under 18 or new to foraging, always work with an experienced guide. For adults, start with easily identifiable species like Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus), which has unique, dangling spines instead of gills. By combining gill analysis with broader ecological awareness, you’ll not only identify mushrooms safely but also deepen your connection to the natural world.

Are Lobster Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging and Cooking

You may want to see also

Cap shape and texture evaluation

The cap, or pileus, is often the most distinctive feature of a mushroom, and its shape and texture can provide crucial clues to its identity. When evaluating cap shape, consider its overall form: is it convex, flat, or depressed? Convex caps, like those of the button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), are common and often indicate young, developing fungi. As mushrooms mature, caps may flatten or even become funnel-shaped, as seen in the chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*). Depressed caps, with a central dip, are less common but characteristic of species like the fairy ring mushroom (*Marasmius oreades*). Observing these shapes in different stages of growth can refine your identification skills.

Texture is equally revealing. A cap’s surface may be smooth, like the glossy skin of the shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*), or scaly, as in the lion’s mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*). Some caps, such as those of the puffball (*Calvatia gigantea*), start off smooth but develop a textured or cracked appearance as they age. Run your fingers gently over the cap to assess its feel—is it slimy, dry, or velvety? For instance, the slippery jack (*Suillus luteus*) has a notably sticky cap due to a thick layer of mucus. Texture can also indicate freshness; a dry, brittle cap may suggest the mushroom is past its prime.

One practical tip for beginners is to compare cap textures across species. For example, the smooth, waxy cap of the witch’s hat (*Hygrocybe conica*) contrasts sharply with the fibrous, hairy surface of the enoki (*Flammulina velutipes*). Carrying a small magnifying lens can help you examine finer details, such as the presence of tiny scales or fibrils. Always note whether the texture changes with moisture—some caps become more slippery when wet, while others retain their dryness.

Caution is essential when evaluating texture, as some toxic mushrooms mimic edible ones in this regard. The deadly Amanita species, for instance, often have smooth, attractive caps that resemble those of edible varieties. Always cross-reference texture with other characteristics, such as color, gill structure, and habitat. A single trait is never enough to confirm edibility.

In conclusion, cap shape and texture are vital tools in mushroom identification. By systematically observing these features—convex or flat, smooth or scaly, dry or sticky—you can narrow down possibilities and make more informed decisions. Practice by examining both edible and non-edible species side by side, and always consult a field guide or expert when in doubt. Mastery of these details transforms mushroom hunting from guesswork into a precise, rewarding skill.

Are Inocybe Mushrooms Edible? Risks, Identification, and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.61 $8.95

$21.74 $24.95

Stem features and presence of veil

The stem of a mushroom is a critical feature for identification, often revealing more than meets the eye. Patrick Harding emphasizes examining the stem’s texture, color, and shape as foundational steps. A fibrous or smooth stem can distinguish between species, while a bulbous base may indicate a toxic variety. For instance, the stem of the edible *Boletus edulis* is stout and often netted, whereas the deadly *Amanita ocreata* has a smooth, fragile stem. Always note if the stem feels sturdy or brittle, as this can be a decisive factor in edibility.

One of the most revealing stem features is the presence or absence of a veil. A veil, or volva, is a membrane that partially or fully encases the young mushroom, often leaving remnants at the base of the stem or cap. Harding warns that a persistent veil at the stem base is a red flag, as it is commonly found in the toxic *Amanita* genus. However, not all veiled mushrooms are dangerous; the edible *Volvariella volvacea*, for example, has a distinctive volva but is safe when properly identified. Always inspect the stem base for veil remnants and cross-reference with other features to avoid misidentification.

To assess stem features effectively, follow these steps: First, gently dig around the mushroom base to expose the entire stem, ensuring no details are missed. Second, use a magnifying glass to examine the texture and color, noting any irregularities. Third, check for a veil by looking for a cup-like structure at the base or remnants on the stem. If a veil is present, avoid consumption unless you are absolutely certain of the species. Harding recommends documenting these observations with photos or notes for future reference.

While stem features and veils are invaluable for identification, they are not foolproof. Misinterpretation can lead to dangerous outcomes, as some toxic mushrooms mimic edible ones in these aspects. For instance, the *Galerina marginata*, a deadly species, has a slender stem and partial veil, resembling the edible *Armillaria*. Harding advises against relying solely on stem features; always corroborate with other characteristics like spore color, gill attachment, and habitat. When in doubt, consult an expert or avoid consumption altogether.

In conclusion, mastering stem features and veil presence is a cornerstone of mushroom identification, but it requires precision and caution. By combining careful observation with broader contextual clues, you can enhance your ability to distinguish edible species from their toxic counterparts. Remember, the goal is not just to identify mushrooms but to do so safely, ensuring every foraging expedition ends on a positive note.

Can You Eat Crimini Mushrooms Raw? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Habitat and seasonal growth patterns

Mushrooms thrive in specific environments, and understanding their preferred habitats is crucial for successful foraging. Edible species often favor deciduous or coniferous forests, where they form symbiotic relationships with trees. Look for them near oak, beech, or pine trees, as these are common hosts. The forest floor, rich in organic matter, provides the ideal conditions for mycelium growth, the vegetative part of the fungus. This network of thread-like cells remains hidden beneath the soil or wood, only revealing its presence when it fruits—the mushrooms we see and harvest.

Seasonal Growth Patterns: A Forager's Calendar

The appearance of edible mushrooms is a seasonal spectacle, with different species emerging at various times of the year. Spring brings the morel mushrooms, a highly prized delicacy, often found in woodland areas with well-drained soil. As summer arrives, chanterelles start to fruit, favoring the acidic soil of coniferous forests. These golden treasures can be abundant, but their season is relatively short-lived. In the fall, the forest floor transforms into a mycologist's paradise, with a wide variety of mushrooms on display. This is the time for porcini, also known as cep, which can be found in both deciduous and coniferous woods, often near birch or pine trees.

A Word of Caution: Timing is Critical

While seasonal patterns provide a general guide, it's essential to note that mushroom growth is highly dependent on local climate and weather conditions. A warm, wet spring may bring an early flush of morels, while a dry summer could delay or reduce the chanterelle crop. Foragers must be adaptable, keeping a close eye on weather patterns and being prepared to adjust their search accordingly. Additionally, some mushrooms have look-alikes that appear in similar seasons, so accurate identification is crucial.

Practical Tips for Foraging Success

To maximize your chances of finding edible mushrooms, consider the following:

- Research Local Species: Familiarize yourself with the mushrooms native to your region and their specific habitat preferences.

- Keep a Foraging Journal: Record the locations and dates of successful finds to build a personal database of productive sites.

- Check Weather Conditions: Monitor rainfall and temperature, as these factors significantly influence mushroom growth.

- Be Patient and Persistent: Mushroom foraging requires dedication; some days you may find an abundance, while other outings yield nothing.

- Learn from Experts: Join local mycological societies or foraging groups to gain practical knowledge and experience.

By understanding the intricate relationship between mushrooms, their habitat, and seasonal changes, foragers can embark on a rewarding journey, discovering the delights of the forest while ensuring a safe and sustainable harvest. This knowledge is a powerful tool, transforming a casual walk in the woods into a fascinating quest for nature's hidden treasures.

Are Jack O' Lantern Mushrooms Edible? A Toxic Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Patrick Harding is a mycologist and expert in mushroom identification with extensive experience in foraging and teaching. His knowledge and publications make him a trusted authority on safely identifying edible mushrooms.

Patrick Harding emphasizes observing spore color, gill structure, cap shape, and habitat. He also stresses the importance of using field guides and consulting experts to avoid toxic look-alikes.

Yes, Patrick Harding suggests using a hand lens, a knife for examining mushroom features, and a field guide or app. He also advises keeping a journal to document findings for future reference.

Patrick Harding warns against relying solely on color, assuming all mushrooms in a group are safe, or eating mushrooms without proper identification. He stresses the importance of certainty to avoid poisoning.