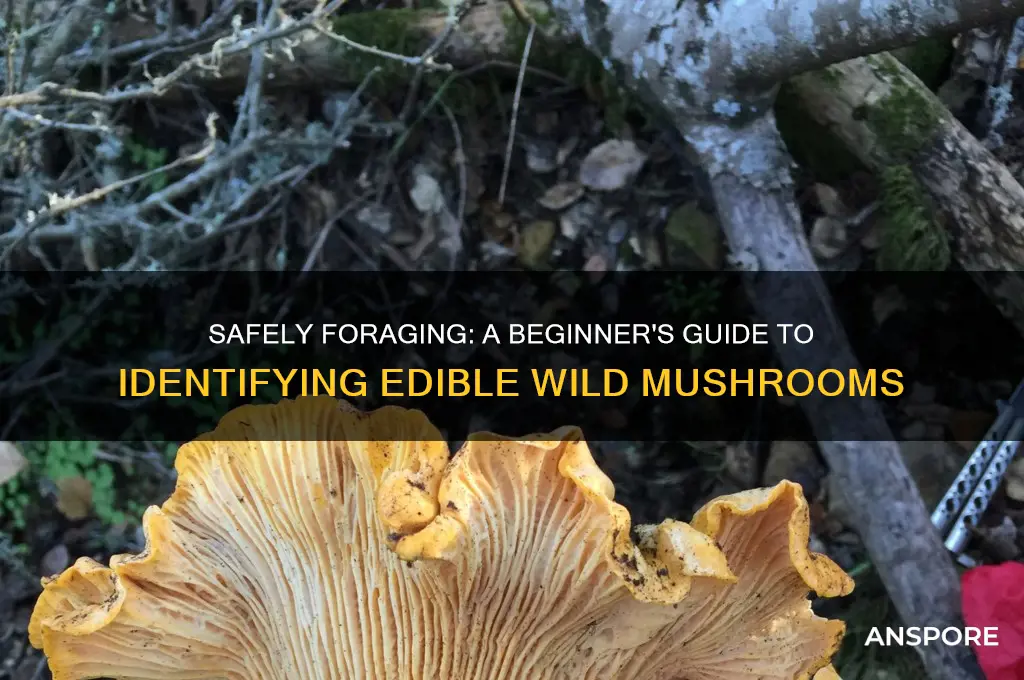

Identifying edible wild mushrooms requires a combination of knowledge, caution, and attention to detail, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even fatality. Start by familiarizing yourself with common edible species in your region, such as chanterelles, morels, and lion’s mane, and learn their distinctive features, including cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. Always use reliable field guides or consult with experienced foragers, and avoid mushrooms with red on the cap or stem, a white spore print, or those growing near polluted areas. Conduct a spore print test, smell for unusual odors, and perform a small taste test (after proper identification) to rule out toxic varieties. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its edibility, and when in doubt, throw it out.

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Spore Print Analysis: Collect spores on paper to identify mushroom species by color and pattern

- Gill and Cap Features: Examine gill attachment, cap shape, and color for key identification clues

- Stem Characteristics: Check for rings, volvas, and stem texture to differentiate edible from toxic types

- Habitat and Season: Learn where and when edible mushrooms grow to narrow down possibilities

- Smell and Taste Tests: Use odor and cautious taste tests (if safe) to confirm edibility

Spore Print Analysis: Collect spores on paper to identify mushroom species by color and pattern

A spore print is a simple yet powerful tool for identifying mushroom species, offering a glimpse into the hidden world of fungal reproduction. By capturing the spores released by a mushroom's gills, you can reveal a unique color and pattern that serves as a fingerprint for identification. This method is particularly useful for distinguishing between similar-looking species, some of which may be edible, while others could be toxic or even deadly.

To create a spore print, start by selecting a mature mushroom with open gills or pores. Place the cap on a sheet of white paper, with the gills facing downward, and cover it with a glass or bowl to maintain humidity. After 2-24 hours, depending on the species, the spores will have fallen onto the paper, creating a distinct pattern. The color of the spore print can range from white and cream to shades of brown, black, purple, or even red. For instance, the spore print of the edible Lion's Mane mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) is typically white, while the toxic Amanita species often produce white or cream-colored spores, highlighting the importance of considering multiple identification factors.

The process of spore print analysis is both an art and a science. It requires patience, attention to detail, and a willingness to learn from both successes and failures. When collecting spores, ensure the mushroom cap is clean and free from debris, as contaminants can distort the print. Additionally, using a black paper alongside the white one can help enhance the visibility of lighter-colored spores. This technique is especially valuable for foragers targeting species like the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), known for its vibrant yellow-gold spore print, or the Morel (Morchella spp.), which produces a distinctive pale cream to yellow print.

One of the key advantages of spore print analysis is its accessibility. Unlike DNA sequencing or chemical tests, this method requires minimal equipment and can be performed with everyday materials. However, it's crucial to remember that spore print color and pattern are just one piece of the identification puzzle. Always cross-reference your findings with other characteristics, such as cap shape, gill attachment, and habitat, to make a confident identification. Misidentification can have serious consequences, so when in doubt, consult a local mycological society or an experienced forager.

In the realm of wild mushroom foraging, spore print analysis stands as a testament to the beauty of nature's intricacies. By mastering this technique, you not only enhance your ability to identify edible species but also deepen your appreciation for the complex world of fungi. As you venture into the woods, armed with your spore print knowledge, remember that each mushroom holds a story waiting to be uncovered – one spore at a time. With practice and persistence, you'll soon find yourself deciphering the subtle nuances of spore colors and patterns, unlocking the secrets of the forest floor.

Identifying Edible Mushrooms: Safe Foraging Tips and Warning Signs

You may want to see also

Gill and Cap Features: Examine gill attachment, cap shape, and color for key identification clues

The gills of a mushroom are its underside ribs, and their attachment to the stem can be a critical identifier. Gills can be free (not attached to the stem), adnate (broadly attached), or adnexed (narrowly attached). For instance, the Chanterelle, a prized edible mushroom, has forked, free gills that run down the stem, giving it a distinctive appearance. In contrast, the deadly Amanita often has white, crowded gills that are free from the stem. Observing this feature closely can help distinguish between safe and toxic species. Always use a magnifying glass or a mushroom field guide to verify gill attachment, as subtle differences can be crucial.

Cap shape and texture are equally revealing. Conical caps often belong to young mushrooms, while flat or umbrella-shaped caps typically indicate maturity. The Shaggy Mane, an edible mushroom, has a cylindrical cap that eventually turns into a melting, inky mess—a unique feature that aids identification. Textures vary too: smooth caps may belong to the edible Button Mushroom, while scaly or fibrous caps could indicate a Boletus species, some of which are edible but require careful preparation. Avoid mushrooms with slimy caps, as this can be a sign of decay or toxicity.

Color is perhaps the most immediate visual clue, but it’s also the most deceptive. While the bright yellow-orange cap of the Chanterelle is a giveaway, many toxic mushrooms also have vivid colors. For example, the red-capped Amanita muscaria is poisonous despite its striking appearance. Always cross-reference color with other features. A practical tip: carry a color chart or use a mushroom identification app to compare hues accurately. Note that colors can fade or darken with age or exposure to sunlight, so examine multiple specimens if possible.

To summarize, gill attachment, cap shape, and color are interdependent features that require careful examination. Start by noting gill attachment—free, adnate, or adnexed—and compare it to known species. Next, assess the cap’s shape and texture, considering developmental stages. Finally, analyze color critically, avoiding reliance on it alone. For beginners, practice on common, easily identifiable species like the Lion’s Mane (hericium erinaceus) or the Oyster Mushroom (pleurotus ostreatus), both of which have distinctive gill and cap features. Always consult multiple sources and, when in doubt, seek expert advice.

Are Black Trumpet Mushrooms Edible? A Tasty Forager's Guide

You may want to see also

Stem Characteristics: Check for rings, volvas, and stem texture to differentiate edible from toxic types

The stem of a mushroom is more than just a support structure; it’s a treasure trove of clues for identifying whether a fungus is safe to eat. One of the first features to examine is the presence of a ring—a remnant of the partial veil that once connected the cap to the stem. Edible species like the Paddy Straw Mushroom (*Coprinus comatus*) often have a movable ring, while toxic look-alikes such as the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*) may also have a ring but lack other safe characteristics. Always cross-reference the ring with other traits, as its presence alone is not a definitive indicator of edibility.

Another critical stem feature is the volva, a cup-like structure at the base of the stem. This is a red flag, as it is commonly found in the highly toxic Amanita genus, including the infamous Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). Edible mushrooms rarely, if ever, have a volva. If you spot this feature, err on the side of caution and avoid consumption entirely. Even experienced foragers treat volva-bearing mushrooms with extreme skepticism, as misidentification can have fatal consequences.

Beyond rings and volvas, stem texture plays a pivotal role in identification. Edible mushrooms like the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) typically have smooth, firm stems, while toxic species such as the False Chanterelle (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*) may have brittle or fibrous textures. A practical tip is to gently squeeze the stem—edible varieties often retain their shape, whereas toxic ones might crumble or feel unusually soft. This simple test can help narrow down your options in the field.

When analyzing stem characteristics, it’s essential to adopt a multi-trait approach. For instance, the Lion’s Mane Mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), prized for its culinary and medicinal properties, has a unique, cascading stem texture with no ring or volva. In contrast, the toxic Jack-O’-Lantern Mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*) has a smooth stem but emits a bioluminescent glow—a warning sign. By combining observations of rings, volvas, and texture, you can build a more accurate profile of the mushroom in question.

Finally, documentation and comparison are your best allies. Carry a field guide or use a trusted app to cross-reference stem characteristics with known species. For beginners, focus on learning the stems of common edible mushrooms first, such as the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which has a laterally attached stem with no ring or volva. Avoid experimenting with unfamiliar species until you’ve mastered these foundational traits. Remember, the stem is not just a structural element—it’s a key to unlocking the safety of your wild harvest.

Are Orange Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat and Season: Learn where and when edible mushrooms grow to narrow down possibilities

Edible mushrooms are not random forest dwellers; they form symbiotic relationships with specific trees and thrive in particular environments. For instance, the prized chanterelle often partners with hardwoods like oak and beech, favoring acidic soil rich in organic matter. In contrast, the porcini mushroom prefers coniferous forests, particularly under pine and spruce trees. Understanding these mycorrhizal associations—where fungi exchange nutrients with tree roots—can significantly narrow your search. A walk through a deciduous woodland might yield morels, while a pine forest could reveal boletes. This ecological insight transforms mushroom hunting from a guessing game into a strategic pursuit.

Seasonality is another critical factor, as edible mushrooms are ephemeral, appearing in response to temperature, humidity, and rainfall. Spring showers bring morels, which emerge in deciduous woods as the soil warms. Summer’s heat and moisture coax chanterelles from the forest floor, while porcini peak in late summer and early fall, coinciding with cooler nights. Foraging in the wrong season is like searching for ripe strawberries in winter—fruitless. Keep a field journal to track local patterns, noting when and where you’ve found species in the past. This data becomes your personalized foraging calendar, increasing your chances of success year after year.

While habitat and season provide a framework, microclimates and weather anomalies can disrupt typical patterns. A particularly wet spring may trigger an early morel flush, while a dry summer could delay chanterelles. Elevation also plays a role; mushrooms at higher altitudes often appear later than their lowland counterparts. For example, porcini in mountainous regions may not emerge until September, while those in valleys could appear in August. Flexibility and observation are key—learn to read the forest’s cues, such as leaf litter moisture or recent rainfall, to predict fruiting times.

Caution is paramount, as misidentifying a mushroom based on habitat or season alone can be dangerous. Deadly galerina, for instance, grows in similar conditions to edible honey mushrooms, often on wood chips or stumps. Always cross-reference findings with multiple identification characteristics, such as spore color, gill structure, and odor. Carry a field guide or use a trusted app, but never rely solely on digital tools. Remember, even experts verify their finds—humility and thoroughness are your best allies in the field.

Finally, ethical foraging practices ensure these habitats remain productive for future seasons. Avoid overharvesting by taking only what you need and leaving behind mature specimens to drop spores. Disturb the soil minimally when collecting, as this protects the mycelium network. Respect private property and protected areas, and familiarize yourself with local regulations. By honoring the ecosystems that support edible mushrooms, you contribute to their sustainability, ensuring these seasonal treasures continue to thrive for generations to come.

Are Elephant Ear Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Smell and Taste Tests: Use odor and cautious taste tests (if safe) to confirm edibility

The sense of smell is a powerful tool in the wild mushroom hunter's arsenal, offering a quick and often revealing first impression. Many edible mushrooms have distinct, pleasant aromas that can hint at their identity. For instance, the coveted chanterelle emits a fruity, apricot-like fragrance, while the porcini mushroom boasts a nutty, earthy scent reminiscent of fresh soil after rain. These olfactory cues can be immediate indicators of edibility, guiding foragers toward a delicious find. However, it's crucial to remember that some toxic mushrooms also have appealing smells, so this test should never be the sole identifier.

Taste, a more daring sensory evaluation, can provide further confirmation but demands extreme caution. The principle here is simple: a tiny amount, a brief contact. Start by touching a small piece of the mushroom to your tongue, noting any immediate reactions like burning, numbness, or bitterness. If there's no adverse effect, you can proceed to a minimal taste test. Chew a small portion and spit it out immediately, assessing the flavor and any aftertaste. Edible mushrooms often have a mild, pleasant taste, but again, this isn't foolproof. Some poisonous varieties can taste good, and the consequences of a mistake can be severe. This method is best reserved for experienced foragers who can recognize the mushroom's other identifying features.

For the adventurous forager, the taste test can be a thrilling but risky endeavor. It's essential to understand the potential dangers and take a measured approach. Begin with a microscopic amount, no larger than a grain of rice, and wait at least 24 hours before considering a slightly larger sample. This gradual exposure allows you to monitor for any delayed reactions. Never consume a wild mushroom without positive identification through multiple characteristics, and always cook it thoroughly, as some toxins are neutralized by heat.

In the realm of mushroom identification, smell and taste tests offer a sensory journey, but they require a delicate balance between curiosity and caution. These methods are most effective when combined with other identification techniques, such as examining physical features and habitat. For beginners, it's advisable to focus on visual identification and consult expert guides or local mycological societies. As your knowledge grows, you can incorporate these sensory tests to enhance your foraging skills, always respecting the potential risks and the fascinating complexity of the fungal world.

While the idea of using smell and taste to identify edible mushrooms is enticing, it's a practice that demands respect and restraint. The consequences of misidentification can be severe, and these tests should never be the sole basis for consumption. Instead, they serve as additional tools in a comprehensive identification process, adding a layer of sensory engagement to the art and science of mushroom foraging. With proper education and a cautious approach, foragers can safely explore the delightful aromas and flavors of the forest's fungal treasures.

Are Russula Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Identification and Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Always use multiple reliable field guides, consult with experienced foragers, and verify characteristics like cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity.

No, there are no universal signs. Some poisonous mushrooms resemble edible ones, so thorough identification is crucial. Avoid relying on myths like "bugs eat it, so it’s safe" or "it smells good."

Bring a knife for clean cutting, a basket for airflow (not a plastic bag), a notebook for notes, and a field guide or mushroom identification app. A magnifying glass can also help examine small details.

If in doubt, throw it out. Do not taste or cook a mushroom you’re unsure about. Consult an expert or mycological society for help with identification.