Identifying flesh-eating poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina is a critical skill for foragers and nature enthusiasts, as misidentification can lead to severe health risks, including tissue necrosis and organ failure. North Carolina’s diverse ecosystems, ranging from mountainous forests to coastal plains, harbor a variety of mushroom species, including dangerous ones like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) and the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*). These toxic fungi often resemble edible varieties, making accurate identification essential. Key features to examine include cap color, gill structure, spore print, and the presence of a volva or ring on the stem. Additionally, understanding seasonal growth patterns and habitat preferences can aid in avoidance. Consulting local mycological guides, attending workshops, and using reliable field guides are invaluable resources for safely navigating the state’s fungal landscape.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Common Toxic Species in NC

North Carolina is home to a diverse array of mushroom species, including several that are toxic and can cause severe health issues, such as tissue necrosis or "flesh-eating" symptoms. Identifying these dangerous mushrooms is crucial for foragers and outdoor enthusiasts. One of the most notorious toxic species in the region is Amanita ocreata, though it is less common than its cousin, Amanita bisporigera, which is more frequently encountered in North Carolina. Both belong to the Amanita genus, often referred to as "Destroying Angels," and contain amatoxins that can cause liver and kidney failure, as well as tissue damage if ingested. These mushrooms have a white to creamy cap, white gills, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva, making them resemble harmless button mushrooms. However, their toxic nature makes proper identification essential.

Another common toxic species in North Carolina is Clitocybe dealbata, also known as the Ivory Funnel. This mushroom is often mistaken for edible chanterelles due to its pale cream color and funnel-shaped cap. It contains muscarine toxins, which can cause sweating, salivation, abdominal pain, and, in severe cases, respiratory failure. The Ivory Funnel typically grows in wooded areas and can be identified by its smooth cap, decurrent gills (gills that extend down the stem), and lack of a distinct odor. Foragers should avoid any funnel-shaped mushrooms unless they are absolutely certain of their identification.

Galerina marginata, or the Funeral Bell, is another highly toxic species found in North Carolina. This small, brown mushroom often grows on decaying wood and contains amatoxins similar to those in Amanitas. Its unassuming appearance—a rusty brown cap, slender stem, and gills that turn yellowish-brown with age—can lead to accidental ingestion. Symptoms of poisoning include severe gastrointestinal distress, liver damage, and potential tissue necrosis if left untreated. Proper identification requires careful examination of its habitat and microscopic features, such as its rusty brown spores.

Lastly, Gyromitra caroliniana, a false morel found in North Carolina, poses a significant risk due to its gyromitrin toxins. These toxins can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms, seizures, and even death if ingested in large quantities. False morels have a brain-like, wrinkled cap and a stout stem, distinguishing them from true morels, which have a honeycomb-like cap. Cooking does not always eliminate the toxins, making avoidance the safest option. Foragers should familiarize themselves with the differences between true and false morels to prevent accidental poisoning.

In summary, North Carolina’s toxic mushroom species, such as Amanitas, Clitocybe dealbata, Galerina marginata, and Gyromitra caroliniana, require careful identification to avoid severe health risks. Key features to look for include cap and gill color, stem structure, habitat, and microscopic characteristics. When in doubt, it is always best to consult an expert or avoid consumption altogether. Education and caution are paramount in safely navigating the state’s rich mycological landscape.

Risks of Consuming Old Mushrooms: Symptoms, Safety, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Key Identification Features

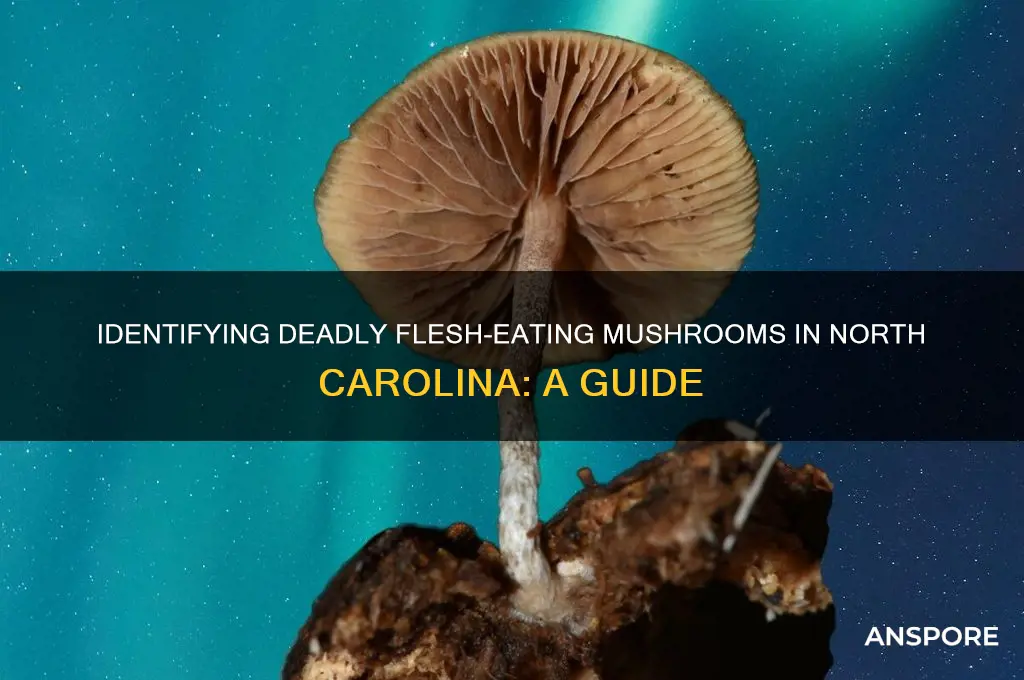

When identifying flesh-eating poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina, it's crucial to focus on key morphological features that distinguish toxic species from edible ones. One of the most notorious flesh-eating mushrooms is the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera* and *Amanita ocreata*), which thrives in wooded areas. These mushrooms have a pure white to creamy cap, often with a smooth or slightly fibrous texture, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva. The gills are white and closely spaced, and the stem is smooth with a movable ring (partial veil remnants). Another dangerous species is the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*), which grows on wood and has a brown, conical cap, a thin stem, and rust-colored spores. Always examine the cap color, shape, and texture, as well as the stem structure and base characteristics, to identify these deadly fungi.

Another critical feature to observe is the gill attachment and spore color. Poisonous mushrooms like the Destroying Angel and Deadly Galerina typically have white gills that attach freely to the stem. To confirm toxicity, collect spores by placing the cap gill-side down on a dark surface overnight and observe their color. These species often produce white spores, which can be a red flag. In contrast, edible mushrooms usually have spores in shades of brown, black, or purple. Additionally, note the presence of a ring on the stem or remnants of a universal veil, which are common in *Amanita* species and indicate potential danger.

The stem characteristics are equally important in identification. Flesh-eating mushrooms often have a fragile, slender stem that may bruise or discolor when handled. The Destroying Angel, for instance, has a smooth, white stem with a skirt-like ring and a bulbous base. In contrast, the Deadly Galerina has a thin, brittle stem that grows directly from wood. Look for bulbs, volvas, or sheaths at the base of the stem, as these are hallmark features of many toxic *Amanita* species. If the mushroom has a tapering or club-shaped stem with a distinct base structure, it warrants extreme caution.

Habitat and seasonality play a significant role in identifying poisonous mushrooms. Flesh-eating species in North Carolina often grow in deciduous or mixed forests, particularly under oak, hickory, and beech trees. The Destroying Angel typically appears in late summer to early fall, while the Deadly Galerina can be found year-round on decaying wood. Always note the substrate—whether the mushroom is growing on soil, wood, or in association with specific trees. Poisonous mushrooms often form mycorrhizal relationships with certain tree species, so understanding their ecological preferences is essential for accurate identification.

Lastly, odor and taste tests are not reliable methods for identifying poisonous mushrooms, as some toxic species may have mild or pleasant scents. Instead, focus on visual cues and microscopic features like spore shape and size. For example, the Destroying Angel and Deadly Galerina have elliptical, smooth spores under a microscope, which can help confirm their identity. Always carry a field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app, and when in doubt, avoid consumption entirely. Proper identification of these key features can save lives and prevent severe poisoning from flesh-eating mushrooms in North Carolina.

Pilgrims' Feast: Did Mushrooms Grace Their Thanksgiving Table?

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning

Consuming poisonous mushrooms, particularly those with flesh-eating or necrotic properties, can lead to severe and potentially life-threatening symptoms. In North Carolina, where a variety of toxic mushrooms grow, recognizing these symptoms early is crucial for prompt medical intervention. The onset of symptoms can vary depending on the type of mushroom ingested, but generally, they fall into distinct categories based on the toxin involved. For necrotic mushrooms, such as those containing orellanine (found in species like *Cortinarius* or "webcaps"), symptoms may not appear for several days, often 2 to 14 days after ingestion. This delayed onset can make diagnosis challenging, as individuals may not immediately associate their symptoms with mushroom consumption.

Initial symptoms of poisoning from flesh-eating mushrooms often include gastrointestinal distress, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These symptoms can be mistaken for food poisoning or a stomach virus, but they are typically more severe and persistent. As the toxins begin to affect the body, individuals may experience dehydration due to prolonged vomiting and diarrhea, which can lead to weakness, dizziness, and confusion. In cases of orellanine poisoning, kidney damage is a primary concern, as the toxin selectively targets renal tissue, leading to acute kidney injury. Symptoms of kidney failure, such as reduced urine output, swelling in the legs or face, and fatigue, may develop within 3 to 20 days after ingestion.

Another critical symptom to watch for is the development of skin lesions or necrosis, particularly with mushrooms containing toxins like coprine or certain unidentified compounds. These toxins can cause localized tissue damage, leading to redness, swelling, blistering, or even death of skin cells. In severe cases, this necrosis can spread, causing systemic issues and requiring surgical intervention to remove affected tissue. Additionally, some poisonous mushrooms may induce neurological symptoms, such as muscle cramps, confusion, hallucinations, or seizures, depending on the specific toxin involved.

In North Carolina, mushrooms like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) or the Fool’s Mushroom (*Amanita verna*) contain amatoxins, which cause severe liver and kidney damage. Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning typically appear within 6 to 24 hours and include severe gastrointestinal distress followed by a brief period of apparent improvement, after which liver failure symptoms emerge. These include jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), dark urine, and abdominal swelling due to fluid accumulation. Without immediate medical treatment, including liver transplantation in severe cases, amatoxin poisoning can be fatal.

It is essential to seek medical attention immediately if poisoning is suspected, even if symptoms seem mild or delayed. Bringing a sample of the mushroom or a detailed description to the hospital can aid in identification and treatment. Early intervention, including gastric decontamination, supportive care, and, in some cases, specific antidotes, can significantly improve outcomes. Awareness of these symptoms and swift action are key to preventing long-term damage or fatality from flesh-eating poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina.

Do Jack Rabbits Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Their Dietary Habits

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe Foraging Practices

When foraging for mushrooms in North Carolina, safety must be your top priority, especially given the presence of potentially deadly species like the destructive "flesh-eating" mushrooms, which can cause severe tissue damage. Safe foraging practices begin with education and preparation. Before heading into the woods, invest time in learning about the common mushroom species in your area, both edible and toxic. Purchase reputable field guides specific to North Carolina’s fungi or enroll in a local mycology class. Familiarize yourself with the characteristics of poisonous mushrooms, such as the Owl’s Eye Mushroom (Clitocybe acromelalga) or Poison Pie (Hebeloma) species, which can cause skin irritation or systemic symptoms. Never rely solely on online images or apps, as misidentification is common.

Always forage with an expert until you are confident in your identification skills. Local mycological societies or foraging groups in North Carolina often organize guided walks, which are excellent opportunities to learn from experienced foragers. When collecting mushrooms, use a knife to cut the base of the stem rather than pulling them out, as this preserves the mycelium and ensures the mushroom’s features remain intact for identification. Carry a basket or mesh bag to allow spores to disperse, aiding in the fungi’s life cycle. Avoid foraging in contaminated areas, such as roadside ditches or industrial sites, where mushrooms may absorb toxins.

Proper identification is critical to safe foraging. Examine mushrooms closely, noting key features like cap shape, color, gills, spores, stem characteristics, and any unusual odors or textures. For instance, some toxic mushrooms have a distinct musty smell or slimy texture. Document your findings with detailed notes and photographs, but never taste or smell a mushroom as a means of identification, as this can be dangerous. If in doubt, discard the mushroom—it’s better to err on the side of caution.

Handling and storage are equally important to prevent accidental exposure to toxins. Wear gloves when collecting or handling unfamiliar mushrooms, especially if they have a sticky or irritating surface. Wash your hands thoroughly after foraging and avoid touching your face. Store collected mushrooms in a cool, dry place and consume or preserve them promptly. If you suspect you’ve come into contact with a toxic mushroom, wash the affected area with soap and water and seek medical attention immediately.

Finally, document and report unusual or potentially dangerous species to contribute to local mycological knowledge. North Carolina’s diverse ecosystems support a wide variety of fungi, and reporting rare or toxic species can help researchers and foragers alike. Safe foraging is a blend of knowledge, caution, and respect for nature. By following these practices, you can enjoy the rewarding hobby of mushroom hunting while minimizing risks to your health and the environment.

Creative Ways to Enjoy Mushrooms Without Detecting Their Flavor

You may want to see also

Local Expert Resources

When it comes to identifying flesh-eating poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina, tapping into local expert resources is crucial for accurate and safe information. One of the most reliable resources is the North Carolina Mycological Society (NCMS), a community of mushroom enthusiasts and experts dedicated to the study and identification of fungi. The NCMS offers workshops, forays (guided mushroom hunts), and identification sessions where you can bring specimens for expert analysis. Their members are well-versed in the local fungal flora, including toxic species like the destructive Amanita species, which can cause severe tissue damage.

Another invaluable resource is the North Carolina State University (NCSU) Cooperative Extension Service. This organization provides science-based educational resources and often collaborates with mycologists to offer workshops on mushroom identification. Their county-based offices can connect you with local experts or provide literature on poisonous mushrooms specific to North Carolina. Additionally, NCSU’s Plant Disease and Insect Clinic can assist with fungal identifications, though it’s primarily focused on plant pathogens, it can still be a useful starting point.

For hands-on learning, consider attending foraging classes led by certified mushroom experts in North Carolina. Local experts like Alan Muskat of No Taste Like Home offer guided foraging tours that include lessons on identifying toxic mushrooms, such as the flesh-eating species found in the region. These classes often emphasize the importance of proper identification techniques, such as examining spore prints, gill structure, and habitat, to avoid dangerous look-alikes.

Hospitals and poison control centers are also critical local expert resources in case of accidental ingestion. The Carolina Poison Center provides 24/7 assistance for mushroom poisoning cases and can guide you on immediate steps to take if you suspect ingestion of a toxic species. They work closely with healthcare providers and mycologists to identify the mushroom involved and recommend appropriate treatment.

Lastly, local libraries and bookstores in North Carolina often carry field guides specific to the region, such as *Mushrooms of the Carolinas* by Alan Bessette and Arleen Bessette. While not a human resource, these guides are curated by local experts and can serve as a quick reference tool. Pairing these guides with advice from mycologists or extension services ensures a comprehensive approach to identifying flesh-eating poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina. Always remember, when in doubt, consult a local expert before handling or consuming any wild mushroom.

Should You Dry Magic Mushrooms Before Consumption? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Flesh-eating mushrooms, or those causing necrotic skin reactions, are rare. In North Carolina, the most concerning species is *Clathrus archeri* (Octopus Stinkhorn), though it’s not commonly deadly. Look for bright orange-red, tentacle-like structures with a foul odor. Avoid touching or consuming any unfamiliar mushrooms.

Poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina often have white gills, a bulbous base, or a ring on the stem. Examples include the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) and the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*). However, no single rule applies to all toxic species, so always consult a guide or expert.

Avoid touching or handling the mushroom. Take a photo from a safe distance and consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide to identify it. Do not attempt to remove it yourself, as some species can release spores or irritants when disturbed.

Apps like iNaturalist or Mushroom Observer can assist with identification, but they are not foolproof. Always cross-reference findings with a local expert or mycological society. Physical field guides specific to North Carolina mushrooms are also highly recommended.

Symptoms vary by species but may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dizziness, or skin irritation. In severe cases, organ failure or necrosis can occur. Seek immediate medical attention if poisoning is suspected, and bring a sample of the mushroom (if safely collected) for identification.