Identifying fungal spores is a crucial skill for mycologists, botanists, and enthusiasts alike, as it allows for the accurate classification and study of fungi. Fungal spores are microscopic reproductive structures that vary widely in shape, size, and color, making their identification both challenging and fascinating. To begin, one must collect a spore sample using techniques such as spore prints or tape lifts, followed by mounting the sample on a microscope slide for detailed examination. Key characteristics to observe include spore color, size, shape (e.g., round, oval, or elongated), surface texture (smooth or ornamented), and septation (presence of internal divisions). Additionally, tools like a spore size chart, caliper, and reference guides are invaluable for comparison. Advanced methods, such as staining or molecular analysis, may also be employed for precise identification. Understanding these features not only aids in species recognition but also contributes to broader ecological and medical research.

What You'll Learn

- Microscopic Examination: Use high-power microscopes to observe spore size, shape, and surface details

- Spore Coloration: Identify spores by their natural pigmentation under light or UV

- Germination Tests: Cultivate spores on media to observe growth patterns and structures

- Molecular Techniques: Use DNA sequencing or PCR for precise species identification

- Environmental Clues: Assess habitat, substrate, and associated organisms to narrow down spore types

Microscopic Examination: Use high-power microscopes to observe spore size, shape, and surface details

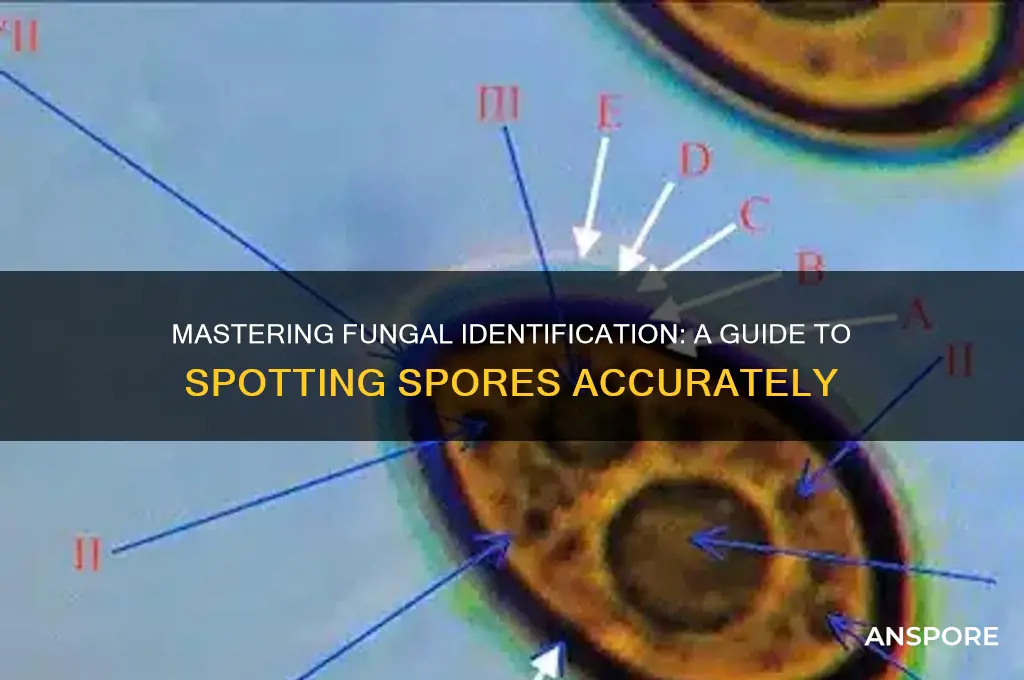

Under a high-power microscope, fungal spores reveal their unique identities through subtle yet distinct characteristics. Size matters—spore diameters range from 2 to 100 micrometers, with most falling between 5 and 20 micrometers. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores typically measure 3-5 micrometers, while *Cladosporium* spores are larger, around 10-20 micrometers. Calibrate your microscope to a 40x or 100x objective lens to capture these minute differences accurately. A micrometer scale slide is essential for precise measurements, ensuring you don’t misidentify species due to magnification errors.

Shape is another critical identifier. Spores can be spherical, oval, cylindrical, or even kidney-shaped. *Penicillium* spores, for example, are flask-shaped, while *Fusarium* spores are elongated and sickle-like. Sketching or photographing these shapes under the microscope aids in comparison with reference guides. Surface details, such as ridges, spines, or smooth walls, further refine identification. *Alternaria* spores, for instance, exhibit distinct septa and long beaks, visible only under high magnification. Use oil immersion techniques for clearer resolution of these fine structures.

To maximize accuracy, prepare spore samples using a wet mount technique. Place a drop of water or lactophenol cotton blue stain on a slide, add a small spore sample, and cover with a coverslip. The stain enhances contrast, making cell walls and internal structures more visible. Avoid overloading the slide, as clumping can obscure individual spores. For dry mounts, tap the fungal colony gently over the slide to release spores, but this method may lack the clarity of wet mounts for detailed examination.

Caution is necessary when handling fungal samples, especially those suspected to be pathogenic. Wear gloves and work in a well-ventilated area or biosafety cabinet to prevent inhalation of spores. Clean microscope slides and tools with 70% ethanol after use to avoid cross-contamination. Misidentification can lead to incorrect treatments or ecological mismanagement, so cross-reference findings with multiple sources, such as mycological atlases or online databases like the Fungal Spores Atlas.

In conclusion, microscopic examination is a cornerstone of fungal spore identification. By meticulously observing size, shape, and surface details under high magnification, you can differentiate between species with confidence. Pair this technique with proper sample preparation, safety precautions, and reference tools to ensure accurate and reliable results. Mastery of this method transforms the microscope into a powerful tool for both research and practical applications in fields like medicine, agriculture, and environmental science.

Can Antibiotics Kill Spores? Unraveling the Science Behind Resistance

You may want to see also

Spore Coloration: Identify spores by their natural pigmentation under light or UV

Fungal spores often reveal their identity through distinct natural pigmentation, a feature that can be observed under standard light or ultraviolet (UV) conditions. This coloration ranges from subtle hues to vibrant shades, each potentially indicative of specific fungal species. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores may appear green or gray, while *Penicillium* spores often exhibit blue-green tones. Recognizing these color patterns is a foundational step in spore identification, as it narrows down possibilities before further analysis.

To leverage spore coloration effectively, begin by examining samples under a bright, white light source. Note the initial color and any variations across the spore mass. For more nuanced identification, employ a UV lamp (365 nm wavelength) to detect fluorescence, a phenomenon where spores emit light of a different color when exposed to UV. For example, *Claviceps purpurea* spores fluoresce under UV, appearing bright yellow-green. Always document these observations with detailed notes or photographs, as subtle differences can distinguish between closely related species.

While spore coloration is a powerful tool, it is not without limitations. Environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and substrate can alter pigmentation, leading to false identifications. Additionally, some spores may appear colorless or exhibit minimal variation, requiring supplementary methods like microscopy or DNA analysis. To mitigate these challenges, cross-reference your findings with established databases or consult mycological literature. For beginners, start with common species like *Alternaria* (brown-black spores) or *Fusarium* (pinkish spores) to build confidence in color-based identification.

Practical tips for optimizing spore coloration analysis include using a clean, glass slide to mount samples, ensuring even distribution of spores for consistent observation. Avoid overexposure to UV light, as prolonged exposure can degrade spore structures. For field collections, store samples in airtight containers to preserve natural pigmentation. By combining careful observation with these techniques, spore coloration becomes a reliable and accessible method for identifying fungal species, offering a visual shortcut in the complex world of mycology.

Effective Techniques for Filtering Spores from Culture Media in Labs

You may want to see also

Germination Tests: Cultivate spores on media to observe growth patterns and structures

Fungal spores, though microscopic, hold the key to understanding fungal diversity and behavior. Germination tests serve as a powerful tool to unlock this potential by providing a controlled environment for spores to sprout and reveal their unique characteristics.

Imagine a petri dish, a miniature arena where spores, once dormant, awaken and stretch towards life. This is the essence of a germination test, a technique that allows us to witness the birth of fungal colonies and decipher their identities.

The Process Unveiled:

To conduct a germination test, a precise protocol is followed. A sterile growth medium, often agar-based and enriched with nutrients, is prepared. This medium acts as the nurturing soil for the spores. A measured quantity of spore suspension, typically ranging from 100 to 1000 spores per milliliter, is carefully inoculated onto the surface. The petri dish is then sealed and incubated at optimal temperature and humidity, mimicking the fungus's natural environment.

Over time, under the right conditions, spores germinate, sending out delicate hyphae that intertwine to form a network called a mycelium. This mycelium, visible to the naked eye, exhibits distinct growth patterns, textures, and colors, offering valuable clues for identification.

Observing the Unfolding Drama:

The beauty of germination tests lies in the visual narrative they present. Some fungi produce rapidly spreading, cottony mycelia, while others grow slowly, forming dense, compact colonies. Colors range from pure white to vibrant greens, browns, and even blacks. Certain species may even produce specialized structures like fruiting bodies or spores within the colony, further aiding identification.

By meticulously documenting these growth patterns, textures, and colors, along with factors like growth rate and response to different media compositions, mycologists can compare the observed characteristics against known fungal profiles, narrowing down the possibilities and ultimately identifying the fungus.

Beyond Identification:

Germination tests transcend mere identification. They provide insights into fungal viability, allowing researchers to assess spore health and germination potential. This is crucial for studying fungal ecology, understanding disease transmission, and developing effective control strategies. Furthermore, these tests can reveal a fungus's nutritional preferences, its tolerance to environmental stressors, and its potential for producing bioactive compounds, opening doors to biotechnological applications.

In essence, germination tests transform the microscopic world of fungal spores into a tangible, observable phenomenon, offering a window into the fascinating realm of fungi and their diverse roles in our world.

Mastering Spore Warden Builds: Essential Tips and Strategies for Success

You may want to see also

Molecular Techniques: Use DNA sequencing or PCR for precise species identification

Fungal spores are notoriously difficult to identify based on morphology alone, as many species exhibit similar physical characteristics. This is where molecular techniques step in, offering a precise and reliable solution. DNA sequencing and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have revolutionized fungal identification, providing a level of accuracy that traditional methods often lack. By targeting specific genetic markers, these techniques can differentiate between closely related species, even those with indistinguishable spore structures.

The Power of DNA Sequencing: Imagine having a unique genetic fingerprint for every fungal species. DNA sequencing makes this possible. This method involves extracting and amplifying a specific region of the fungal genome, typically the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, which is highly variable and species-specific. The ITS region is a popular choice due to its ability to discriminate between closely related fungi. Once amplified, the DNA sequence is compared to a reference database, such as GenBank, where millions of fungal sequences are stored. A close match reveals the species identity with remarkable precision. For instance, a study on *Aspergillus* species demonstrated that DNA sequencing accurately identified isolates to the species level, even when morphological characteristics were inconclusive.

PCR: A Rapid and Sensitive Approach: PCR is a versatile technique that can be tailored for various fungal identification scenarios. Real-time PCR, for example, allows for the simultaneous detection and quantification of multiple fungal species in a single reaction. This is particularly useful in environmental samples where numerous species coexist. By designing species-specific primers, researchers can target unique DNA sequences, ensuring accurate identification. A recent application of PCR in mycology involves the detection of fungal pathogens in clinical samples, where rapid and early diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment. For instance, a PCR assay for *Candida* species can provide results within hours, significantly faster than traditional culture methods.

Practical Considerations: Implementing molecular techniques requires careful planning and optimization. Laboratory setup is critical, ensuring a sterile environment to prevent DNA contamination. The choice of DNA extraction method is vital, as it affects the quality and yield of fungal DNA. Commercial kits are available, offering reliable and consistent results. When designing PCR primers, it's essential to consider the target region's conservation across the species of interest and its variability to ensure specificity. Additionally, the use of positive and negative controls is imperative to validate the accuracy of the assay.

Advantages and Applications: Molecular techniques offer several advantages over traditional identification methods. They provide rapid results, often within hours, compared to days or weeks for culture-based methods. The sensitivity of PCR allows for the detection of low-abundance species, which might be missed in morphological examinations. These techniques are particularly valuable in medical mycology, where swift and accurate identification of fungal pathogens is essential for patient treatment. Furthermore, DNA sequencing contributes to the growing fungal genome databases, aiding in the discovery and classification of new species. As technology advances, these molecular tools will become more accessible and affordable, making precise fungal spore identification a standard practice in various fields, from agriculture to environmental monitoring.

Cooking and Mold: Can Heat Destroy Spores in Food Safely?

You may want to see also

Environmental Clues: Assess habitat, substrate, and associated organisms to narrow down spore types

Fungal spores don't materialize in a vacuum. Their presence is intimately tied to the environment they inhabit. By scrutinizing the habitat, substrate, and associated organisms, you can significantly narrow down the identity of the spores you're examining. Imagine finding spores on a decaying log in a damp forest. This immediately suggests a wood-decomposing fungus, eliminating countless other possibilities.

A coniferous forest floor, rich in acidic humus, will host different fungal species than a calcareous grassland. Similarly, spores found on a living oak leaf likely belong to a pathogen or epiphyte, while those on a fallen, decaying leaf point towards saprotrophs.

This environmental detective work extends beyond broad habitat types. The specific substrate – the material the spores are growing on – is crucial. Are the spores on wood, soil, animal dung, or perhaps a living plant? Each substrate harbors distinct fungal communities. For instance, the genus *Coprinus* is known for its association with dung, while *Amanita* species often form mycorrhizal relationships with tree roots.

Observing associated organisms can further refine your identification. Lichens, for example, are composite organisms consisting of a fungus and a photosynthetic partner (algae or cyanobacteria). Finding spores in close association with lichenized algae strongly suggests a lichen-forming fungus.

This environmental approach isn't foolproof. Some fungi are generalists, thriving in diverse habitats. However, by carefully considering the ecological context, you can significantly reduce the pool of potential candidates, making spore identification a far more manageable task. Think of it as a process of elimination, where each environmental clue brings you closer to the correct answer.

Stanford's Intramural Sports Programs: Opportunities for Students to Get Active

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Key characteristics include spore shape (e.g., round, oval, or elongated), size, color, texture (smooth or rough), and any distinctive features like spines or appendages.

Fungal spores often have consistent shapes, sizes, and structures specific to their species, whereas other particles like dust or pollen may appear irregular or lack uniformity.

Essential tools include a microscope (preferably with high magnification), a spore collection device (e.g., tape or slides), and reference guides or databases for comparison.

While some spores may be visible to the naked eye in large quantities, a microscope is necessary for accurate identification due to their microscopic size and detailed features.

Yes, different fungal spores thrive in specific conditions, such as high humidity for mold spores or wooded areas for certain mushroom spores. Knowing the environment can aid identification.