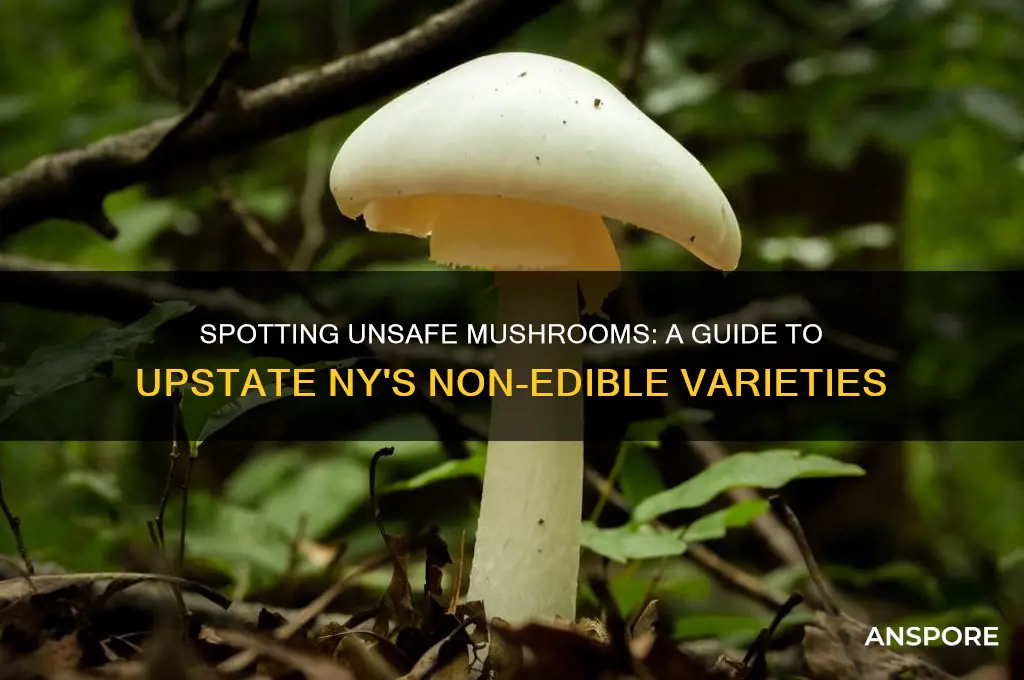

Identifying non-edible mushrooms in Upstate New York is crucial for foragers and nature enthusiasts to avoid accidental poisoning. The region’s diverse ecosystems, ranging from dense forests to open meadows, host a wide variety of mushroom species, many of which are toxic or inedible. Key characteristics to look for include vivid or unusual colors, such as bright red, yellow, or white, which often signal danger. Other warning signs include the presence of a skirt-like volva at the base of the stem, a bulbous base, or a slimy cap. Additionally, mushrooms that bruise easily or emit a strong, unpleasant odor are often unsafe to consume. Familiarizing oneself with common toxic species like the Amanita genus, which includes the deadly Death Cap and Destroying Angel, is essential. Always consult reliable field guides or local mycological experts, and remember the golden rule: never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Color and Texture: Bright colors, slimy textures often indicate toxicity; avoid mushrooms with these traits

- Gill and Spore Check: White or colored spores, unusual gill patterns can signal danger

- Habitat Clues: Growing near poisonous plants or in polluted areas may be toxic

- Odor and Taste: Foul smells or bitter tastes are warning signs; never taste-test

- Common Toxic Species: Learn to spot Amanita, Galerina, and other deadly mushrooms in the region

Color and Texture: Bright colors, slimy textures often indicate toxicity; avoid mushrooms with these traits

Bright colors in mushrooms often serve as a warning sign in nature, a phenomenon known as aposematism. This evolutionary strategy deters predators by signaling toxicity or unpleasant taste. In upstate New York, vivid reds, yellows, and oranges on mushroom caps or stems should raise caution. For instance, the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), with its iconic red cap dotted with white, is psychoactive and can cause severe gastrointestinal distress. Similarly, the False Chanterelle (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*), though resembling edible chanterelles, displays a bright orange color and should be avoided due to its potential to cause stomach upset. While not all brightly colored mushrooms are toxic, their striking appearance warrants careful scrutiny and, often, avoidance.

Texture plays an equally critical role in identifying potentially toxic mushrooms. A slimy or sticky surface, particularly on the cap or stem, can indicate the presence of harmful compounds or bacteria. For example, the Slime-Coated Oysterling (*Crepidotus mollis*) has a gelatinous texture and is not recommended for consumption due to its unpalatable nature and potential toxicity. Similarly, mushrooms with a greasy or viscid feel, such as certain species in the *Hygrocybe* genus, often contain compounds that can cause allergic reactions or digestive issues. When foraging in upstate New York, avoid mushrooms with unusual textures, especially if they feel unusually wet or slippery, as these traits often correlate with toxicity or spoilage.

To apply these principles in the field, follow a systematic approach. First, observe the mushroom’s color under natural light, noting any unusually bright or contrasting hues. Second, gently touch the cap and stem to assess texture; use gloves to avoid skin irritation from potentially harmful substances. If the mushroom feels slimy, sticky, or greasy, err on the side of caution and leave it undisturbed. Third, cross-reference your findings with a reliable field guide or mushroom identification app, paying close attention to toxic look-alikes. For instance, the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*), with its bright orange color and slimy texture, closely resembles edible chanterelles but is highly toxic and causes severe cramps and diarrhea.

While color and texture are valuable indicators, they are not foolproof. Some toxic mushrooms, like the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*), have dull colors and unremarkable textures, making them deceptively dangerous. Conversely, a few edible species, such as the Velvet Foot (*Flammulina velutipes*), have slimy caps when young but are safe to eat after proper preparation. Therefore, rely on a combination of traits, including spore color, gill attachment, and habitat, to make an informed decision. If in doubt, consult an experienced mycologist or avoid consumption altogether. Remember, the goal is not just to identify non-edible mushrooms but to ensure safety in the diverse fungal landscapes of upstate New York.

Cultivating Edible Mushrooms: A Guide to Sustainable Public Consumption

You may want to see also

Gill and Spore Check: White or colored spores, unusual gill patterns can signal danger

The gills of a mushroom, often hidden beneath the cap, are a treasure trove of information for foragers. These delicate, radiating structures are not just aesthetically pleasing; they play a crucial role in spore production and can be a key indicator of a mushroom's edibility. In upstate New York, where the forests are abundant with fungi, understanding the language of gills and spores is essential for any aspiring mycophile.

A Colorful Warning: One of the most straightforward methods to identify potentially toxic mushrooms is by examining their spore color. White spores are generally considered safer, as many edible mushrooms, like the beloved button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), produce them. However, this is not a hard and fast rule. Some toxic species, such as the deadly *Amanita ocreata*, also have white spores, emphasizing the need for additional identification methods. On the other hand, brightly colored spores, such as pink, green, or black, often indicate a mushroom's toxicity. For instance, the vibrant green spores of the *Chlorophyllum molybdites* are a clear warning sign, as this mushroom is known to cause severe gastrointestinal distress.

Unusual Gill Patterns: Beyond spore color, the arrangement and attachment of gills can provide valuable insights. Typically, gills are closely spaced and attached to the stem, but variations from this norm can be significant. For example, gills that are widely spaced or have a unique attachment, such as running down the stem (decurrent gills), may indicate a different species. The Lion's Mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), with its cascading, tooth-like spines instead of gills, is an edible exception, but such deviations often warrant caution.

Practical Tips for Foragers: When conducting a gill and spore check, it's essential to handle mushrooms with care. Gently lift the cap to expose the gills, and if possible, take a spore print. This involves placing the cap, gill-side down, on a piece of paper or glass for several hours. The resulting spore deposit will reveal its color and pattern. For beginners, it's advisable to start with easily identifiable species and always cross-reference multiple field guides or consult local mycological societies for accurate identification.

In the diverse fungal landscape of upstate New York, the gill and spore check is a critical step in mushroom identification. While it doesn't provide a definitive answer, it offers valuable clues, especially when combined with other identification techniques. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to develop a deep understanding of the fascinating world of fungi, where every color, pattern, and structure tells a story.

Can You Eat Baby Portabella Mushroom Stems? A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Habitat Clues: Growing near poisonous plants or in polluted areas may be toxic

Mushrooms absorb their surroundings with alarming efficiency, often concentrating toxins from soil, air, and nearby flora. This means a seemingly harmless species growing in a polluted area—near busy roads, industrial sites, or treated lawns—can accumulate heavy metals like lead or pesticides, rendering it unsafe for consumption. Similarly, mushrooms in close proximity to poisonous plants may absorb or mimic their toxins, a phenomenon known as allelopathy. For instance, fungi near poison hemlock or white snakeroot in upstate NY could pose hidden risks, even if they resemble edible varieties.

To leverage habitat clues effectively, start by mapping your foraging area. Avoid zones within 500 feet of high-traffic roads or agricultural fields where pesticide drift is common. Test soil for contaminants using home kits (available for $20–$50) if you suspect pollution. When scouting woodlands, note the presence of toxic plants like poison ivy, mayapple, or water hemlock—mushrooms nearby may have absorbed their defensive chemicals. For example, *Clitocybe dealbata*, a toxic species, often grows near oak trees alongside edible lookalikes, highlighting the need for vigilance.

Contrast this with pristine habitats: mushrooms in old-growth forests or remote areas are less likely to harbor toxins. However, even here, allelopathy can occur. For instance, *Amanita ocreata* thrives near oak roots in California, mimicking the benign *Amanita velosa* but causing severe poisoning. In upstate NY, *Amanita muscaria* (fly agaric) often grows near birch trees, a red flag despite its iconic appearance. Always cross-reference habitat with known toxic species in your region.

A persuasive argument for caution: no amount of cleaning or cooking can eliminate certain toxins absorbed from the environment. Boiling, for instance, reduces bacterial contamination but does nothing to remove heavy metals or plant-derived poisons. Similarly, peeling or trimming mushrooms grown in polluted areas is ineffective against systemic toxins. If in doubt, discard specimens from questionable habitats entirely—the risk of misidentification or contamination far outweighs the reward of a meal.

Instructively, develop a habitat checklist for safer foraging: 1) Avoid areas with visible pollution or nearby toxic plants. 2) Prioritize undisturbed ecosystems like deep forests or meadows far from human activity. 3) Research local toxic species and their preferred habitats. 4) When in doubt, consult a mycologist or use a testing kit for heavy metals. Remember, habitat is not definitive proof of edibility, but it’s a critical layer of protection against unseen dangers.

Are Purple Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Odor and Taste: Foul smells or bitter tastes are warning signs; never taste-test

A mushroom's aroma can be a powerful indicator of its edibility, and in the forests of Upstate New York, this sensory clue should not be overlooked. The presence of a strong, unpleasant odor is nature's way of waving a red flag. For instance, the toxic *Clitocybe dealbata*, commonly known as the Ivory Funnel, emits a distinct, pungent smell reminiscent of garlic or onions, which should immediately raise concerns. This is a critical lesson for foragers: trust your sense of smell. If a mushroom's fragrance is off-putting or unusual, it's a clear signal to proceed with caution.

Taste, however, is a different matter altogether. The age-old advice to 'taste a small bit and wait' is a dangerous myth. Even a tiny amount of certain mushrooms can be harmful, and symptoms may not appear immediately, making it a risky and unreliable method. The *Galerina marginata*, a deadly mushroom often found in the same habitats as edible species, has been mistaken for its edible counterparts due to its similar appearance. A single bite can lead to severe poisoning, emphasizing the importance of never using taste as a test. This is especially crucial for children, who may be more inclined to put things in their mouths, and the elderly, who might have a diminished sense of taste, making them more susceptible to accidental poisoning.

The key to safe foraging lies in understanding that these sensory warnings are not mere suggestions but critical indicators. Foul odors and bitter tastes are nature's defense mechanisms, evolved to deter consumption. For instance, the bitter taste of the *Hypholoma fasciculare*, or Sulfur Tuft, is a clear sign of its toxicity. This mushroom, often found in clusters on wood, can cause gastrointestinal distress, highlighting the importance of heeding these natural warnings.

In the context of Upstate New York's diverse mycoflora, where both delicious and dangerous mushrooms thrive, it is essential to approach foraging with a comprehensive understanding of these sensory cues. While visual identification is crucial, the addition of odor and taste analysis provides a more robust safety net. For beginners, it is advisable to start with easily identifiable, distinctively scented species like the anise-scented *Clitopilus prunulus* (The Miller), ensuring a safer introduction to the world of mushroom foraging. Always remember, when in doubt, throw it out—a simple rule that could save lives.

Are White Lawn Mushrooms Edible? A Safe Foraging Guide

You may want to see also

Common Toxic Species: Learn to spot Amanita, Galerina, and other deadly mushrooms in the region

Upstate New York’s forests are teeming with mushrooms, but not all are safe to eat. Among the most dangerous are species from the *Amanita* and *Galerina* genera, which contain potent toxins like amatoxins and orellanine. A single bite of *Amanita ocreata* or *Galerina marginata* can lead to severe liver or kidney failure within hours. Learning to identify these deadly species is crucial for foragers, as misidentification can be fatal. Always remember: when in doubt, throw it out.

To spot *Amanita* species, look for key features like a volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and gills that are typically white. The "Destroying Angel" (*Amanita bisporigera*) and "Death Cap" (*Amanita phalloides*) are particularly notorious in the region. Both have smooth caps, often greenish or white, and can resemble edible varieties like the meadow mushroom. A critical tip: *Amanitas* often have a collar-like ring on the stem, but its absence doesn’t rule out toxicity. If you find a mushroom with a volva, assume it’s deadly until proven otherwise.

Galerina species are smaller and less showy but equally dangerous. Often found on decaying wood, they have rusty-brown spores and a slender, fibrous stem. Galerina marginata, commonly called the "Funeral Bell," is easily mistaken for edible Psathyrella or Pholiota species. A key identifier is its gill attachment—Galerina gills often notch or run down the stem slightly. If you’re foraging near wood, scrutinize small brown mushrooms carefully, as Galerina thrives in these habitats.

Beyond *Amanita* and *Galerina*, other toxic species like *Conocybe filaris* (a lawn-dwelling lookalike of *Agaricus* species) and *Clitocybe dealbata* (the "Ivory Funnel," which causes severe gastrointestinal distress) are present in the region. These mushrooms often lack the dramatic features of *Amanitas* but are no less dangerous. A practical tip: carry a spore print kit. Rusty-brown spores, as seen in *Galerina*, or olive-brown spores, as in *Conocybe*, can be red flags.

The takeaway is clear: identification requires meticulous attention to detail. Relying on single traits like color or habitat is risky. Instead, examine multiple features—spore color, gill attachment, stem base, and habitat—and cross-reference with reliable guides. Foraging classes or local mycological clubs can provide hands-on training. Remember, no wild mushroom is worth risking your life. If you’re unsure, leave it be—the forest will always offer another opportunity.

Speckled Mushrooms: Edible Delights or Toxic Threats? A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Non-edible mushrooms often have sharp, pointed caps, bright or unusual colors (like red, white with scales, or vivid yellow), and may have a slimy or sticky texture. They frequently lack a pleasant smell and can have a bitter or unpleasant odor. Some may also have a skirt-like ring on the stem or a bulbous base.

Yes, several poisonous species are found in Upstate NY, including the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), which is deadly and resembles edible mushrooms; the Jack-O’-Lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*), which glows and causes severe gastrointestinal issues; and the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), which contains toxins that can be fatal if not properly prepared.

Always consult a reliable field guide or a local mycologist for accurate identification. Avoid mushrooms with white gills, a bulbous base, or those that bruise easily. Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Joining a local mycological society or attending foraging workshops can also improve your identification skills.