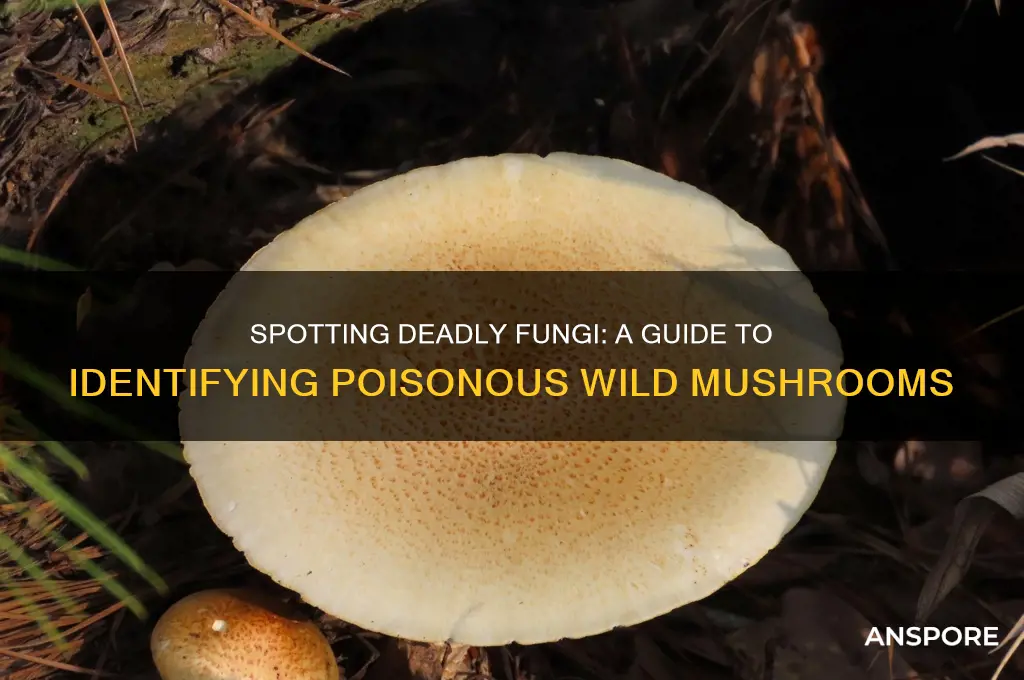

Identifying poisonous wild mushrooms is a critical skill for foragers and nature enthusiasts, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. Key characteristics to examine include the mushroom’s cap shape, color, and texture; the presence or absence of gills, pores, or spines; the color and structure of the stem; and any distinctive odors or tastes. Additionally, observing the mushroom’s habitat, such as the type of soil or trees nearby, can provide valuable clues. While some poisonous mushrooms resemble edible varieties, reliable identification often requires a field guide or expert consultation, as folklore and myths about safety tests (like using silver or animals) are unreliable. Always prioritize caution and avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless absolutely certain of their edibility.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore print color: Check underside for spore color; white, black, or colored prints can indicate toxicity

- Gill attachment: Examine how gills attach to stem; some poisonous types have distinct connections

- Cap features: Look for warts, scales, or unusual colors; these often signal danger

- Stem characteristics: Note rings, bulbs, or sticky textures; toxic mushrooms may have unique stems

- Habitat clues: Avoid mushrooms near certain trees or environments known for poisonous species

Spore print color: Check underside for spore color; white, black, or colored prints can indicate toxicity

The underside of a mushroom cap holds a hidden clue to its nature: the spore print. This often-overlooked detail can be a powerful tool in distinguishing between edible and poisonous fungi. By examining the color of the spores, foragers can gain valuable insights into the mushroom's identity and potential toxicity. A simple yet effective method, creating a spore print is a crucial step in the identification process, especially for those new to mushroom hunting.

Creating a Spore Print: To reveal this secret code, one must carefully remove the mushroom's cap and place it gill-side down on a piece of paper or glass. The spores will drop from the gills, creating a colored imprint. This process can take several hours, so patience is key. The resulting color can vary from pure white to dark black or even vibrant hues, each carrying a different message. For instance, a white spore print is common among many edible mushrooms, such as the beloved button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*). However, it's not a definitive sign of edibility, as some toxic species also produce white spores.

Deciphering the Color Code: Black spore prints are often associated with the genus *Coprinus*, which includes both edible and inedible species. The inky cap mushrooms, known for their unique deliquescing nature, typically fall into this category. Colored spore prints, such as brown, purple, or pink, can be more indicative of toxicity. For example, the deadly *Galerina* species, often mistaken for edible *Armillaria*, produce a rusty brown spore print. Similarly, the poisonous *Cortinarius* genus is known for its purple-brown spores. These colored prints serve as a warning sign, urging foragers to proceed with caution.

Practical Application: When in the field, carrying a small notebook and a collection of colored papers can be invaluable. By quickly creating spore prints on different colored backgrounds, foragers can enhance their ability to discern subtle shades. This technique is especially useful for beginners, providing a tangible reference point. It's essential to remember that spore color is just one piece of the puzzle. Combining this knowledge with other identification methods, such as examining gill attachment, cap shape, and habitat, will significantly reduce the risk of misidentification.

In the world of mycology, where look-alikes and imposters abound, the spore print is a reliable ally. It offers a scientific approach to mushroom identification, moving beyond the realm of guesswork. By mastering this technique, foragers can make more informed decisions, ensuring a safer and more enjoyable mushroom-hunting experience. This simple yet powerful tool empowers enthusiasts to explore the fascinating world of fungi with confidence.

Are Cone Cap Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Gill attachment: Examine how gills attach to stem; some poisonous types have distinct connections

The way a mushroom's gills attach to its stem can be a subtle yet critical clue in distinguishing between edible and poisonous varieties. This often-overlooked feature varies significantly across species, and certain attachments are more commonly associated with toxic mushrooms. For instance, gills that are adnate (broadly attached to the stem) or adnexed (narrowly attached) are typical in many edible species like the Chanterelle. In contrast, free gills, which do not attach to the stem at all, are often found in the highly toxic Amanita genus, including the notorious Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). Observing this detail requires careful examination, as it can be a decisive factor in avoiding dangerous look-alikes.

To inspect gill attachment, gently lift the mushroom cap and observe the point where the gills meet the stem. Use a magnifying glass if necessary, as the connection can be delicate and easily missed. For beginners, it’s helpful to compare findings with reliable field guides or apps that provide detailed illustrations. A practical tip is to note the overall structure: if the gills appear to detach easily from the stem or leave a clean break, this could indicate a free attachment, a red flag for potential toxicity. Always cross-reference this feature with other identifiers, as no single characteristic is foolproof.

From an analytical perspective, gill attachment is a morphological trait influenced by evolutionary adaptations. Free gills, for example, are thought to facilitate spore dispersal in certain environments, but they also correlate with higher toxicity in some species. This raises the question: is there a biological link between gill attachment and toxin production? While research is limited, the pattern suggests that free gills may serve as a warning sign in nature, deterring foragers with their distinctive structure. Understanding this evolutionary context can deepen your appreciation for the intricacies of mushroom identification.

For those new to foraging, mastering gill attachment examination is a skill that develops with practice. Start by collecting samples of known species to familiarize yourself with their gill structures. Caution is paramount: never consume a mushroom based solely on gill attachment. Instead, use it as one piece of a larger puzzle, alongside cap color, spore print, habitat, and other features. A persuasive argument for focusing on gill attachment is its reliability compared to more variable traits like color, which can fade or change with age. By prioritizing this detail, you build a safer, more systematic approach to mushroom identification.

In conclusion, gill attachment is a nuanced but vital characteristic in the quest to identify poisonous wild mushrooms. Its examination requires patience, precision, and a willingness to learn from both successes and mistakes. While it’s not a standalone identifier, it complements other diagnostic features, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the mushroom in question. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced forager, honing this skill can significantly reduce the risk of misidentification and enhance your appreciation for the complexity of the fungal world.

Are Fairy Ink Cap Mushrooms Poisonous? Facts and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Cap features: Look for warts, scales, or unusual colors; these often signal danger

The cap of a mushroom is its most distinctive feature, often the first thing foragers notice. Among the telltale signs of toxicity are warts, scales, or unusual colors. Warts, which appear as small, raised bumps, are particularly suspicious because they can indicate the presence of toxins like amatoxins, found in the deadly Amanita genus. Scales, resembling tiny flakes or patches on the cap, are another red flag, as they often accompany mushrooms that cause gastrointestinal distress or worse. Unusual colors—bright reds, vivid yellows, or garish greens—should also raise concern, as nature often uses bold hues to warn of danger. While not all mushrooms with these features are poisonous, they warrant extreme caution and further investigation.

Consider the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), a notorious example of a mushroom with a smooth, wart-free cap in its mature stage but often displaying a volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and a greenish-yellow hue. Its unassuming appearance belies its deadly nature, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. In contrast, the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), with its bright red cap dotted with white scales, is less lethal but still toxic, causing hallucinations and severe discomfort. These examples illustrate how cap features can serve as critical indicators of danger, even when other parts of the mushroom seem benign.

To safely assess cap features, start by examining the mushroom in its natural habitat without touching it. Use a magnifying glass to inspect warts or scales closely, noting their texture and distribution. Document the color accurately, as lighting conditions can alter perception—what appears orange in the forest might look red in sunlight. If the cap has a sticky or slimy texture, this can also signal toxicity, as seen in some species of *Cortinarius*. Avoid relying solely on color, as some edible mushrooms (like the Chanterelle) can have vibrant hues, while some poisonous ones (like the Destroying Angel) are deceptively pure white.

For novice foragers, a practical tip is to carry a field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app that highlights dangerous cap features. If you encounter a mushroom with warts, scales, or unusual colors, err on the side of caution and leave it undisturbed. Remember, no wild mushroom is worth risking your health. Even experienced foragers cross-reference multiple characteristics, including spore color, gill attachment, and habitat, before making a definitive identification. When in doubt, consult a mycologist or local mushroom club for expert advice.

In conclusion, the cap of a mushroom is a treasure trove of clues about its safety. Warts, scales, and unusual colors are nature’s warning signs, often pointing to toxicity. By observing these features carefully and combining them with other identification methods, foragers can minimize risk and enjoy the thrill of the hunt without endangering themselves. Always prioritize caution over curiosity, and let the cap be your first line of defense in the wild.

Are Violaceus Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Their Edibility

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Stem characteristics: Note rings, bulbs, or sticky textures; toxic mushrooms may have unique stems

The stem of a mushroom is often overlooked, but it can be a critical indicator of its toxicity. One distinctive feature to look for is the presence of a ring or annulus, a remnant of the partial veil that once covered the gills. While not exclusive to poisonous mushrooms, certain toxic species like the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata) often retain this ring, which can be a red flag. Always inspect the stem closely for such structures, especially if the mushroom resembles an edible variety like the common button mushroom.

Another stem characteristic to note is the bulbous base, often accompanied by a cup-like volva at the bottom. This feature is particularly associated with the Amanita genus, which includes some of the most deadly mushrooms in the world, such as the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) and the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera). The bulbous base is a unique adaptation that helps these mushrooms anchor in the soil, but it also serves as a clear warning sign. If you encounter a mushroom with this feature, avoid it entirely, as even a small bite can be fatal.

Sticky or slimy textures on the stem are less common but equally important to recognize. Some toxic mushrooms, like the Sticky Bun (Suillus luteus), have a viscous layer on their stems, which can deter animals and humans alike. While not all sticky mushrooms are poisonous, this texture often indicates a species that is unpalatable or potentially harmful. If you’re unsure, err on the side of caution and leave it untouched. A simple rule of thumb: if the stem feels unusually slippery, it’s best to avoid it.

Foraging safely requires a methodical approach. Start by examining the stem for rings, bulbs, or sticky textures, but don’t stop there. Combine these observations with other identifiers, such as gill color, spore print, and habitat. For instance, a mushroom with a bulbous base and white gills is far more likely to be toxic than one without these features. Always cross-reference your findings with reliable field guides or consult an expert. Remember, misidentification can have severe consequences, so take your time and double-check every detail.

Finally, consider the practical steps for stem inspection. Use a knife to carefully cut the mushroom at ground level, exposing the entire stem structure. Examine it under good light, noting any irregularities. For sticky stems, gently touch the surface with a gloved finger to avoid transferring toxins. If you’re teaching children or beginners, emphasize the importance of focusing on the stem as much as the cap. By making stem characteristics a priority in your identification process, you’ll significantly reduce the risk of accidental poisoning.

Are Trumpet Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Habitat clues: Avoid mushrooms near certain trees or environments known for poisonous species

Certain trees act as silent sentinels, warning foragers of potential danger lurking beneath their canopies. For instance, the majestic oak, a symbol of strength and longevity, often harbors the deadly Amanita ocreata, a fungus that mimics the edible Amanita muscaria but contains potent toxins. Similarly, yew trees, with their dark, needle-like foliage, are frequently accompanied by the Clitocybe dealbata, a deceptively innocuous-looking mushroom that causes severe gastrointestinal distress and, in extreme cases, respiratory failure. Recognizing these arboreal associations can serve as a critical first line of defense against accidental poisoning.

Instructive as it may be, avoiding specific trees is only part of the equation. Environments themselves can be telling indicators of a mushroom’s toxicity. Damp, decaying wood in coniferous forests often hosts the Galerina marginata, a small, unassuming fungus that contains the same deadly amatoxins found in the infamous Death Cap. Conversely, well-drained, grassy areas near hardwoods might be home to the Inosperma erubescens, whose reddish gills belie its ability to cause severe hemolytic anemia. Foraging in these habitats without prior knowledge of their fungal inhabitants is akin to navigating a minefield blindfolded.

Persuasive arguments aside, the practical application of habitat awareness cannot be overstated. A seasoned forager once quipped, “Know the neighborhood before you knock on the door.” This adage holds true when scouting for mushrooms. For example, if you’re in a mixed woodland with both conifers and deciduous trees, exercise caution, as this transitional zone often attracts a diverse array of fungi, including both edible and toxic species. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable app to cross-reference your findings, and when in doubt, leave it out.

Comparatively, the approach to habitat-based identification differs from other methods, such as spore prints or gill examination, in its emphasis on prevention rather than diagnosis. While spore color or cap texture can help identify a mushroom post-collection, habitat clues allow you to avoid risky specimens altogether. For instance, the Cortinarius rubellus, often found in birch forests, closely resembles edible webcaps but contains orellanine, a toxin that causes kidney failure. By steering clear of birch groves during your foraging expeditions, you eliminate the risk of mistaking this deadly doppelgänger for a meal.

Descriptively, imagine a dense, moss-covered forest floor beneath a stand of hemlocks, their needles casting a shadowy, acidic scent into the air. This environment is a favorite of the Conocybe filaris, a slender, nondescript mushroom that packs a punch with its potent toxins. Its presence here is no coincidence; the hemlock’s acidic soil creates the perfect breeding ground for this species. By familiarizing yourself with such ecological preferences, you not only enhance your foraging safety but also deepen your appreciation for the intricate relationships between fungi and their habitats.

Are Russula Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? Poison Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying poisonous mushrooms requires knowledge of key characteristics such as color, shape, gills, spores, and habitat. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert, as some toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones. When in doubt, avoid consumption.

There are no universal signs to identify poisonous mushrooms. Myths like "poisonous mushrooms are brightly colored" or "animals avoid toxic mushrooms" are unreliable. Always rely on specific identification features and expert advice.

If you suspect a mushroom is poisonous, do not touch or consume it. Take detailed notes or photos for identification, and consult a mycologist or poison control center if needed. Proper identification is crucial for safety.