Identifying wild mushrooms in British Columbia (BC) requires careful observation, knowledge of local species, and an understanding of key characteristics such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. BC’s diverse ecosystems, ranging from coastal rainforests to interior woodlands, host a wide variety of fungi, including edible treasures like chanterelles and morels, as well as toxic species like the Death Cap. Beginners should focus on learning common features like the presence of a ring or volva, spore print color, and the mushroom’s smell and texture. Utilizing field guides, mobile apps, and local mycological clubs can aid in accurate identification, while always adhering to the rule of never consuming a mushroom unless 100% certain of its edibility. Safety and respect for the environment are paramount when foraging in BC’s rich fungal landscapes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Common BC Mushroom Species: Learn key varieties like Chanterelles, Morels, and Boletes found in British Columbia forests

- Physical Identification Features: Examine caps, gills, stems, spores, and colors for accurate mushroom classification

- Habitat and Seasonality: Understand where and when specific mushrooms grow in BC’s diverse ecosystems

- Toxic vs. Edible Mushrooms: Spot dangerous species like Amanita and safe ones like Oyster mushrooms

- Field Guide and Tools: Use local guides, apps, and magnifying lenses for precise mushroom identification

Common BC Mushroom Species: Learn key varieties like Chanterelles, Morels, and Boletes found in British Columbia forests

British Columbia’s diverse forests are home to a wide array of wild mushrooms, making it a forager’s paradise. Among the most sought-after species are Chanterelles, Morels, and Boletes, each with distinct characteristics that help identify them. Understanding these key varieties is essential for safe and successful mushroom hunting in BC. Always remember to positively identify mushrooms before consuming them, as some look-alikes can be toxic.

Chanterelles (genus *Cantharellus*) are a favorite among foragers for their fruity aroma and delicate flavor. In BC, the most common species is the *Golden Chanterelle* (*Cantharellus formosus*). These mushrooms have a golden-yellow color, a wavy cap, and forked gills that run down the stem. They are often found in coniferous forests, particularly under Douglas fir and pine trees. To identify them, look for their false gills (ridges and forks) instead of true gills, and their egg-like shape when young. Chanterelles have no poisonous look-alikes in BC, but always check for their characteristic aroma and gill structure.

Morels (genus *Morchella*) are another prized find, known for their honeycomb-like caps and rich, earthy flavor. In BC, the *Yellow Morel* (*Morchella esculenta*) and *Black Morel* (*Morchella elata*) are commonly found in spring, often near recently burned areas or in deciduous forests. Morels have a conical cap with a spongy, pitted surface and a hollow stem. A key identification tip is to ensure the cap attaches to the stem with a seamless connection. Avoid false morels, which have a wrinkled, brain-like appearance and are not safe to eat. Always cut morels in half to confirm they are hollow throughout.

Boletes (family *Boletaceae*) are a large group of mushrooms characterized by their spongy pores instead of gills. In BC, the *King Bolete* (*Boletus edulis*) is highly prized for its meaty texture and nutty flavor. It has a brown cap, a thick white stem, and a pore surface that is white when young and turns greenish-brown with age. Boletes are often found under conifers and can be identified by their pores and the absence of gills. However, not all boletes are edible; some have red pores or stems that bruise blue, indicating toxicity. Always check the pore color and stem reaction when identifying boletes.

When foraging for these common BC mushroom species, it’s crucial to follow ethical practices, such as leaving some mushrooms behind to spore and using a knife to cut the stem rather than pulling them out. Additionally, carry a field guide or use a reliable app to cross-reference your findings. While Chanterelles, Morels, and Boletes are rewarding to find, always prioritize safety and certainty in identification to fully enjoy the bounty of BC’s forests.

Microdosing Mushrooms for Anxiety: Potential Benefits and Risks Explored

You may want to see also

Physical Identification Features: Examine caps, gills, stems, spores, and colors for accurate mushroom classification

When identifying wild mushrooms in British Columbia, physical identification features are your primary tools for accurate classification. Start by closely examining the cap, which is often the most noticeable part of the mushroom. Note its shape—is it convex, flat, or umbonate (with a central bump)? Measure its diameter and observe its texture: is it smooth, scaly, slimy, or fibrous? Some caps change color with age or when bruised, so take note of any variations. For example, the caps of *Lactarius* species often exude a milky substance when damaged. Understanding these cap characteristics is crucial, as they can significantly narrow down the possibilities.

Next, inspect the gills (or pores, teeth, or spines) located beneath the cap, as they play a vital role in spore production. Gills can be free, adnate (broadly attached), or decurrent (extending down the stem). Observe their color, spacing, and thickness. For instance, the gills of the *Amanita* genus are often white and closely spaced, while those of *Boletus* species are replaced by pores. Some mushrooms, like the lion's mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), have teeth instead of gills. These features are key to distinguishing between similar-looking species.

The stem is another critical component. Note its length, thickness, and shape—is it cylindrical, tapering, or club-shaped? Check for a ring (partial veil remnants) or a volva (cup-like structure at the base), which are common in *Amanita* species. The stem's texture, color, and presence of fibers or scales can also provide clues. For example, the stem of the chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) is smooth and often forked, while the destroying angel (*Amanita ocreata*) has a bulbous base with a volva.

Spores are microscopic, but their color and shape are essential for identification. To examine spores, place the cap gill-side down on a piece of paper or glass slide and leave it overnight. The spore print’s color—white, black, brown, or other hues—is a diagnostic feature. For instance, *Coprinus* species produce black spores, while *Agaricus* species typically produce dark brown spores. A hand lens or microscope can further reveal spore shape and size, aiding in precise classification.

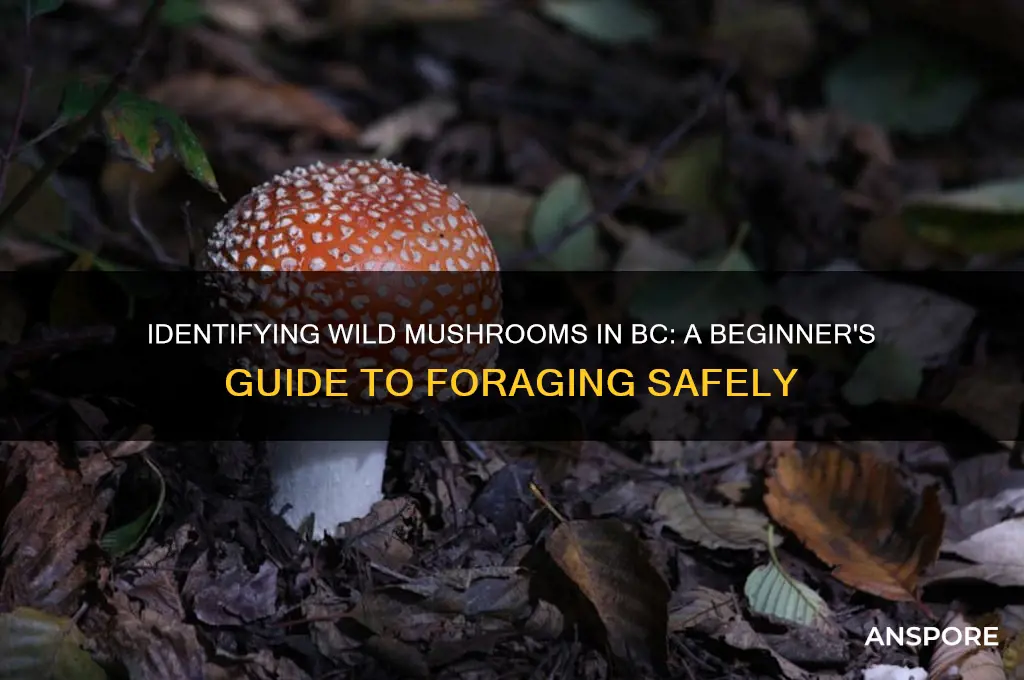

Finally, color is a striking but variable feature. While some mushrooms maintain consistent colors, others change with age, exposure to air, or damage. Document the colors of the cap, gills, stem, and flesh. For example, the golden chanterelle is vibrant yellow, while the fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) has a bright red cap with white spots. Always cross-reference color with other features, as similar colors can appear in unrelated species. By systematically examining caps, gills, stems, spores, and colors, you can confidently identify wild mushrooms in BC and avoid dangerous look-alikes.

Oyster Mushrooms: Safe Treat or Toxic for Cats?

You may want to see also

Habitat and Seasonality: Understand where and when specific mushrooms grow in BC’s diverse ecosystems

British Columbia’s diverse ecosystems provide a rich habitat for a wide variety of wild mushrooms, each with specific environmental preferences. Understanding the habitat of a mushroom is crucial for accurate identification. For instance, mycorrhizal mushrooms, which form symbiotic relationships with trees, are commonly found in forested areas. The coastal rainforests of BC, dominated by conifers like Douglas fir and western hemlock, are prime habitats for species such as the chanterelle (*Cantharellus formosus*). In contrast, saprotrophic mushrooms, which decompose dead organic matter, thrive in areas with abundant fallen logs, leaf litter, or decaying wood. The old-growth forests and wooded areas of Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland are particularly fertile grounds for these fungi.

Seasonality plays a significant role in mushroom foraging, as different species emerge at specific times of the year. In BC, the mushroom season generally begins in late summer and peaks in the fall, though some species appear as early as spring or as late as winter. For example, morels (*Morchella* spp.) are springtime favorites, often found in recently burned areas or deciduous forests. Chanterelles, on the other hand, are most abundant in late summer to early fall, coinciding with cooler, wetter weather. Winter mushrooms, such as the velvet foot (*Flammulina velutipes*), can be found in milder coastal regions, growing on decaying wood even in colder months. Monitoring local weather patterns, particularly rainfall and temperature, is essential for predicting mushroom fruiting times.

Elevation and microclimate also influence mushroom distribution in BC. Higher elevations, such as those in the Rocky Mountains or the Interior Plateau, host alpine and subalpine species adapted to cooler temperatures and shorter growing seasons. Mushrooms like the alpine entoloma (*Entoloma alpinum*) are exclusive to these regions. In contrast, low-lying coastal areas and river valleys support species that prefer milder, more humid conditions. Foragers should consider these factors when planning trips, as a short drive to a different elevation or ecosystem can yield entirely different mushroom species.

Soil type and pH levels are additional habitat factors to consider. Some mushrooms, like the iconic fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), prefer acidic soils commonly found under coniferous trees. Others, such as the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), thrive in neutral to slightly alkaline environments, often growing on hardwood trees. Understanding the soil composition of an area can narrow down the possibilities when identifying mushrooms. Coastal regions with sandy soils may host different species compared to the clay-rich soils of the Interior.

Finally, human-altered environments can also support unique mushroom habitats. Urban parks, gardens, and even woodchip mulch beds can host species like the sulfur tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*) or the common ink cap (*Coprinopsis atramentaria*). Similarly, disturbed areas such as clear-cuts or roadsides may foster opportunistic mushrooms that colonize bare or nutrient-rich soils. While these environments may not be as pristine as old-growth forests, they offer accessible opportunities for beginners to practice mushroom identification. By combining knowledge of habitat and seasonality, foragers can more effectively locate and identify wild mushrooms across BC’s varied landscapes.

How to Kill Mushrooms with Milorganite: Does it Work?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

Toxic vs. Edible Mushrooms: Spot dangerous species like Amanita and safe ones like Oyster mushrooms

When foraging for wild mushrooms in British Columbia, distinguishing between toxic and edible species is crucial for your safety. One of the most notorious toxic genera is Amanita, which includes the deadly "Death Cap" (*Amanita phalloides*) and the destructive "Destroying Angel" (*Amanita ocreata* and *Amanita bisporigera*). These mushrooms often have a distinctive cap with white gills, a skirt-like ring on the stem, and a bulbous base. The Death Cap, for instance, has a greenish-yellow to olive cap and can easily be mistaken for edible species like the Paddy Straw mushroom. To avoid confusion, always look for the telltale signs of Amanitas: the presence of a cup-like volva at the base and a ring on the stem. If you spot these features, it’s best to leave the mushroom alone, as consuming even a small amount can be fatal.

In contrast, Oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are a safe and delicious edible species commonly found in BC. They grow in shelf-like clusters on decaying wood and have a fan- or oyster shell-shaped cap with a smooth, grayish-brown surface. Unlike Amanitas, Oyster mushrooms lack a ring on the stem and do not have a bulbous base. Their gills are decurrent, meaning they run down the stem, which is a key identifying feature. Another edible look-alike is the *Pleurocybella porrigens* (Angel Wing), but it grows on conifers and has a whiter appearance. Always ensure the mushroom you’ve found matches all the characteristics of an Oyster mushroom, as some toxic species like the Jack-O-Lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*) can resemble it but have sharp gills and a bioluminescent quality.

Another dangerous group to watch out for is the Galerina genus, often called "deadly webcaps." These small, nondescript mushrooms grow on wood and can resemble edible species like Honey Mushrooms (*Armillaria*). Galerinas have a rusty-brown spore print and a cortina (a cobweb-like partial veil) when young, which later forms a faint ring on the stem. Unlike the clustered growth of Oyster mushrooms, Galerinas often grow singly or in small groups. Misidentification is common due to their unremarkable appearance, so always check for the rusty spores and avoid any small brown mushrooms growing on wood unless you’re absolutely certain.

To safely identify edible mushrooms, focus on species with well-documented characteristics and avoid those with toxic look-alikes. For example, Chanterelles (*Cantharellus formosus*) are a prized edible mushroom in BC, known for their golden-yellow color, forked gills, and fruity aroma. They lack a ring or volva, and their false gills run down the stem. However, be cautious of the False Chanterelle (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*), which has true gills and a more orange color. Always cross-reference multiple features, such as spore color, habitat, and season, to confirm your identification.

Lastly, when in doubt, leave it out. Relying on a single feature, such as color or shape, is risky. Use field guides, spore prints, and local mycological clubs to verify your findings. Toxic mushrooms like Amanitas and Galerinas can cause severe symptoms, including organ failure, while edible species like Oyster mushrooms and Chanterelles offer a rewarding foraging experience. Always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly before consumption, as some edible species can cause digestive upset when raw. Safe foraging practices ensure you enjoy the bounty of BC’s forests without endangering your health.

Hydrating Dried Mushrooms: Quick and Easy Methods

You may want to see also

Field Guide and Tools: Use local guides, apps, and magnifying lenses for precise mushroom identification

When venturing into the forests of British Columbia to identify wild mushrooms, having the right tools and resources is essential. Field guides specific to BC are invaluable, as they provide detailed information on local species, including their characteristics, habitats, and look-alikes. These guides often include high-quality photographs and descriptions of key features such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and stem details. Popular options include *Mushrooms of British Columbia* by Andy MacKinnon and *Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America* by Roger Phillips. Local guides are particularly useful because they focus on the species you’re most likely to encounter in BC’s diverse ecosystems, reducing confusion and increasing accuracy.

In addition to physical guides, mushroom identification apps have become indispensable tools for foragers. Apps like *PictureThis - Plant Identifier* or *Mushroom ID* allow you to upload photos of mushrooms for instant analysis. Some apps even use AI to compare your find with a database of species, providing probable matches and additional information. While apps are convenient, they should be used as a supplementary tool rather than a sole resource, as their accuracy can vary. Always cross-reference app results with a trusted field guide or expert to ensure correct identification.

A magnifying lens or hand lens is another critical tool for precise mushroom identification. Many distinguishing features, such as spore color or the texture of the cap, are too small to see with the naked eye. A 10x magnifying lens allows you to examine these details closely, which can be the difference between identifying a species correctly or mistaking it for a toxic look-alike. For example, observing the presence of partial veil remnants or the color of the spore print requires magnification. Investing in a durable, portable magnifying lens is a small but significant step toward becoming a skilled mushroom identifier.

Combining these tools—local field guides, apps, and magnifying lenses—creates a robust system for accurate mushroom identification. Start by consulting your field guide to narrow down possibilities based on habitat and visible features. Use your magnifying lens to inspect finer details, and then cross-reference your findings with an app for additional insights. This multi-pronged approach minimizes errors and builds confidence in your identification skills. Remember, proper identification is crucial, as misidentifying mushrooms can have serious consequences.

Lastly, consider joining local mycological clubs or workshops in BC to enhance your knowledge. These groups often provide hands-on experience and access to experts who can guide you in using your tools effectively. By equipping yourself with the right resources and practicing regularly, you’ll become adept at identifying the diverse and fascinating mushrooms found in British Columbia’s wilderness.

How to Clean Mushrooms: Rinse or Wipe?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Focus on the mushroom's cap shape, color, gills or pores, stem characteristics (e.g., ring, bulb, or veil remnants), spore color, and habitat. These features are essential for accurate identification.

Yes, several toxic mushrooms in BC, like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita ocreata*), resemble edible species such as the Paddy Straw Mushroom or Chanterelles. Always double-check identification.

While apps can be helpful, they are not always reliable. It’s best to cross-reference findings with field guides, consult experts, and gain hands-on experience to ensure accuracy.

The prime mushroom foraging season in BC is late summer to fall (August to November), when conditions are moist and temperatures are cooler, promoting fungal growth.

Join local mycological societies, attend guided foraging walks, and study reputable field guides specific to BC. Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification.