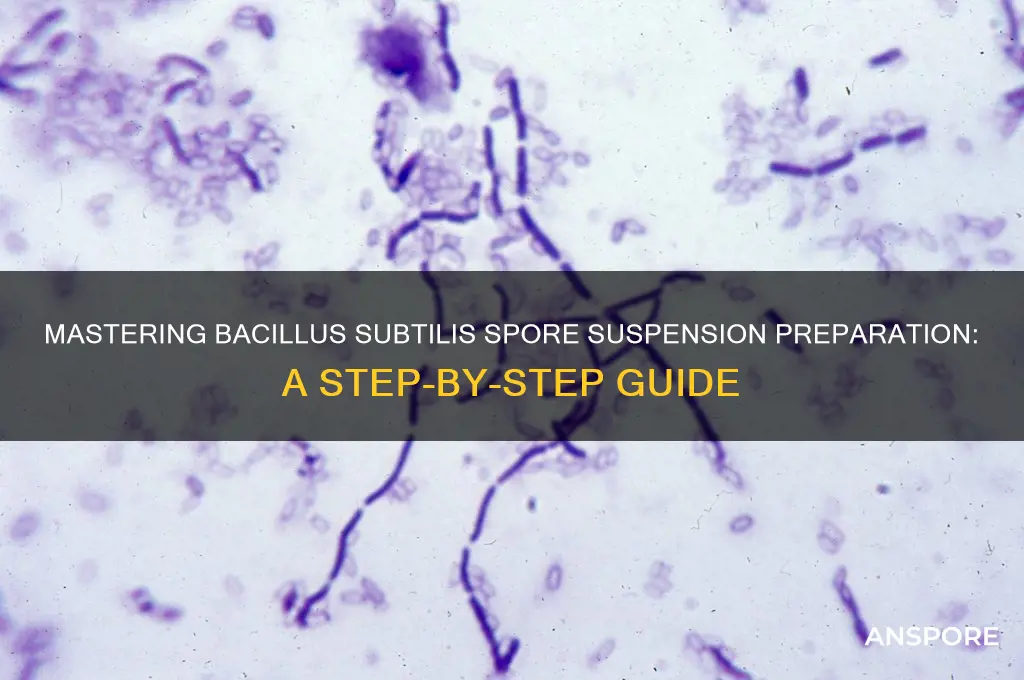

Bacillus subtilis, a Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium, is widely recognized for its ability to form resilient endospores that can withstand harsh environmental conditions. Preparing a spore suspension of Bacillus subtilis is a crucial step in various applications, including biotechnology, agriculture, and research. The process involves cultivating the bacterium under optimal conditions to promote sporulation, followed by harvesting and purifying the spores. Typically, Bacillus subtilis is grown in nutrient-rich media, such as nutrient broth or agar, under controlled temperature and aeration to encourage spore formation. Once sporulation is complete, the spores are separated from the vegetative cells and other debris through centrifugation, washing, and filtration. The resulting spore suspension can be stored for extended periods or used directly in experiments, ensuring a concentrated and viable population of Bacillus subtilis spores for downstream applications.

What You'll Learn

- Spore Induction Methods: Nutrient depletion, stress conditions, and environmental triggers to initiate sporulation in Bacillus subtilis

- Harvesting Spores: Centrifugation, filtration, and washing techniques to isolate spores from culture medium

- Spore Purification: Density gradient centrifugation and chemical treatments to remove cellular debris and contaminants

- Spore Suspension Preparation: Resuspending purified spores in sterile buffer or water to desired concentration

- Storage and Stability: Optimal conditions (temperature, pH, and additives) for long-term spore suspension preservation

Spore Induction Methods: Nutrient depletion, stress conditions, and environmental triggers to initiate sporulation in Bacillus subtilis

Bacillus subtilis, a model organism for studying sporulation, initiates this process in response to specific environmental cues. Among the most effective methods to induce spore formation are nutrient depletion, stress conditions, and environmental triggers. These strategies mimic the natural conditions that signal to the bacterium that resources are scarce, prompting it to enter a dormant, spore-forming state. Understanding these methods is crucial for researchers and industries aiming to produce spore suspensions efficiently.

Nutrient Depletion: A Starvation-Induced Response

One of the most reliable ways to induce sporulation in *B. subtilis* is through nutrient depletion, particularly the exhaustion of carbon and nitrogen sources. When grown in a defined medium, such as DSM (Difco Sporulation Medium) or a modified version like MSgg, cells enter stationary phase as nutrients are depleted. For optimal results, inoculate a culture at an initial OD600 of 0.1 and allow it to grow to late exponential phase (OD600 ~2.0). Transfer the culture to a fresh medium lacking key nutrients, and monitor sporulation over 24–48 hours. Studies show that complete nutrient depletion can achieve sporulation efficiencies of up to 90%. To enhance consistency, maintain a controlled pH (7.0–7.4) and temperature (37°C) during the process.

Stress Conditions: Pushing the Limits

Stress conditions, such as high salinity or osmotic shock, can also trigger sporulation in *B. subtilis*. For instance, exposing cells to 2–4% NaCl or 0.5 M sorbitol during late exponential phase can accelerate spore formation. This method is particularly useful when nutrient depletion alone is insufficient. However, caution is required: prolonged exposure to stress can lead to cell death rather than sporulation. A practical tip is to pre-adapt cells to mild stress (e.g., 1% NaCl) before applying more severe conditions. This two-step approach increases resilience and improves spore yield.

Environmental Triggers: The Role of Temperature and pH

Environmental factors like temperature shifts and pH changes act as subtle yet powerful triggers for sporulation. A temperature downshift from 37°C to 25°C, combined with nutrient depletion, can significantly enhance spore formation. Similarly, a slight decrease in pH (from 7.0 to 6.0) mimics natural soil conditions and promotes sporulation. These triggers are often used in conjunction with other methods to optimize efficiency. For example, a protocol combining nutrient depletion, a temperature downshift, and mild osmotic stress can yield spore suspensions with concentrations exceeding 10^9 spores/mL.

Practical Takeaways and Cautions

While these methods are effective, consistency requires attention to detail. Always sterilize equipment to prevent contamination, as spores are highly resistant and can survive harsh conditions. Monitor cultures regularly using phase-contrast microscopy to confirm spore morphology. For industrial applications, scale-up protocols should account for oxygen availability, as *B. subtilis* is aerobic and requires adequate aeration for efficient sporulation. Finally, store spore suspensions in a buffer containing 20% glycerol at -80°C to preserve viability for future use. By mastering these induction methods, researchers and practitioners can reliably produce high-quality *B. subtilis* spore suspensions tailored to their needs.

Unlocking the Zoologist Badge in Spore: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Harvesting Spores: Centrifugation, filtration, and washing techniques to isolate spores from culture medium

Centrifugation stands as a cornerstone technique in the isolation of *Bacillus subtilis* spores from culture medium, leveraging the density differential between spores and vegetative cells. To begin, transfer the mature spore culture into sterile centrifuge tubes, ensuring the volume does not exceed 80% of the tube's capacity to prevent spillage. Centrifuge at 5,000–7,000 × *g* for 10–15 minutes at 4°C to pellet the spores while keeping the vegetative cells and debris suspended in the supernatant. Carefully decant the supernatant, leaving behind a compact spore pellet. This step can be repeated 2–3 times to enhance purity, though over-centrifugation may damage spore integrity. For small-scale preparations, a benchtop centrifuge suffices, while larger volumes benefit from high-capacity centrifuges with swing-out rotors.

Filtration offers an alternative or complementary method to centrifugation, particularly when dealing with viscous or particulate-rich media. Use a 0.22–0.45 μm pore-size filter to retain spores while allowing smaller contaminants to pass through. Pre-wet the filter with sterile water or buffer to prevent spore adhesion and ensure even flow. Apply gentle vacuum pressure to expedite filtration without compromising spore viability. For large-scale applications, tangential flow filtration systems provide efficient separation, though they require careful monitoring to avoid clogging. Pairing filtration with centrifugation can significantly improve spore purity, especially in cultures with high vegetative cell counts.

Washing techniques are critical to removing residual nutrients, toxins, and cellular debris from the spore pellet, ensuring a clean suspension. Resuspend the pellet in sterile, cold distilled water or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuge again at 5,000 × *g* for 10 minutes. Repeat this washing step at least twice, or until the supernatant appears clear. For stringent purification, incorporate a heat treatment step by incubating the spore suspension at 80°C for 20 minutes to kill any remaining vegetative cells. Alternatively, use a dilute solution of sodium hypochlorite (0.1%) for 10 minutes, followed by thorough washing to remove residual disinfectant. Proper washing not only enhances spore purity but also prolongs suspension stability.

Comparing these techniques reveals their unique strengths and limitations. Centrifugation is rapid and effective but may require multiple rounds for high purity. Filtration excels in removing fine contaminants but can be time-consuming and prone to clogging. Washing is essential for all methods, serving as the final safeguard against impurities. Combining these techniques—starting with centrifugation, followed by filtration, and concluding with rigorous washing—yields the highest purity spore suspension. Practical considerations, such as culture volume, equipment availability, and desired purity level, should guide the selection of the most appropriate method or combination.

In conclusion, mastering centrifugation, filtration, and washing techniques is pivotal for isolating *Bacillus subtilis* spores with optimal purity and viability. Each method addresses specific challenges in spore harvesting, and their strategic integration ensures a robust suspension suitable for downstream applications. Attention to detail, such as maintaining sterile conditions and avoiding mechanical stress, preserves spore integrity throughout the process. Whether for research, industrial, or clinical use, a well-executed harvesting protocol lays the foundation for successful spore suspension preparation.

Vinegar's Power: Can It Effectively Kill Mildew Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore Purification: Density gradient centrifugation and chemical treatments to remove cellular debris and contaminants

Density gradient centrifugation stands as a cornerstone technique in spore purification, leveraging the principle of differential sedimentation to separate spores from cellular debris and contaminants. This method involves layering a spore suspension onto a density gradient medium, such as sucrose or Percoll, followed by high-speed centrifugation. Spores, being denser than most cellular debris, migrate through the gradient and form distinct bands at specific densities. For *Bacillus subtilis* spores, a 50-70% (w/v) sucrose gradient is commonly employed, with centrifugation at 10,000–15,000 × *g* for 30–60 minutes. The spore band is then carefully extracted, diluted, and washed to remove residual gradient material, yielding a highly purified spore suspension. This technique is particularly effective for large-scale purification, ensuring minimal contamination and high spore viability.

While density gradient centrifugation is powerful, it is often complemented by chemical treatments to further refine spore purity. Chemical treatments target specific contaminants, such as residual DNA, proteins, or cell wall fragments, which can interfere with downstream applications. For instance, treatment with DNase (10–50 μg/mL) and RNase (10–20 μg/mL) for 30–60 minutes at 37°C effectively degrades nucleic acids, reducing background in molecular assays. Additionally, protease treatment (e.g., 1 mg/mL proteinase K for 1 hour at 50°C) can eliminate residual proteins. These treatments must be followed by thorough washing, typically via centrifugation at 5,000 × *g* for 10 minutes, to remove enzymes and reaction byproducts. When combined with density gradient centrifugation, these chemical steps ensure a spore suspension of exceptional purity, suitable for applications like vaccination, probiotics, or environmental studies.

A critical consideration in spore purification is the balance between efficacy and spore integrity. While aggressive treatments may yield higher purity, they risk compromising spore viability or structure. For example, prolonged exposure to high concentrations of enzymes or harsh detergents can damage spore coats or exosporium layers. Practitioners must optimize conditions—such as enzyme concentration, incubation time, and temperature—to maximize purity without sacrificing spore functionality. A practical tip is to perform viability assays (e.g., colony-forming unit counts) before and after purification to monitor spore health. This iterative approach ensures that the purification protocol is both effective and gentle, preserving the spores' biological properties.

Comparatively, density gradient centrifugation and chemical treatments offer distinct advantages over alternative methods like filtration or simple washing. Filtration, while straightforward, often fails to remove small contaminants or debris of similar size to spores. Simple washing, though gentle, lacks the precision needed for high-purity suspensions. Density gradient centrifugation, on the other hand, provides a robust physical separation based on density, while chemical treatments address specific molecular contaminants. Together, these methods form a synergistic approach, combining the strengths of both techniques to achieve a level of purity unattainable by either alone. This makes them the gold standard for applications requiring pristine *Bacillus subtilis* spore suspensions.

Are Dead Mold Spores Dangerous? Uncovering the Hidden Health Risks

You may want to see also

Spore Suspension Preparation: Resuspending purified spores in sterile buffer or water to desired concentration

Resuspending purified *Bacillus subtilis* spores in sterile buffer or water is a critical step in spore suspension preparation, ensuring uniformity and viability for downstream applications. The process begins with selecting an appropriate sterile buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or distilled water, which maintains spore integrity without introducing contaminants. The choice of buffer depends on the intended use; for example, PBS is often preferred for its isotonic properties, which minimize osmotic stress on the spores. Once the buffer is prepared, it must be sterilized, typically by autoclaving or filtration through a 0.22 μm filter, to eliminate any microbial competitors or impurities.

The technique for resuspension is as important as the buffer selection. Purified spores, often obtained through heat treatment or density gradient centrifugation, tend to aggregate due to their hydrophobic nature. To achieve a homogeneous suspension, gentle but thorough mixing is essential. A common method involves vortexing the spore-buffer mixture for 10–15 seconds, followed by brief sonication if necessary to break up clumps. Alternatively, a sterile glass rod or pipette can be used for manual agitation, ensuring minimal shear stress that could damage the spores. The goal is to disperse the spores evenly without compromising their structural integrity.

Concentration control is another key aspect of spore suspension preparation. The desired spore concentration varies depending on the application, ranging from 10^6 to 10^9 spores per milliliter for most laboratory uses. To achieve this, the spore pellet is resuspended in a measured volume of buffer, and the suspension is then quantified using a hemocytometer or spectrophotometer. For precise adjustments, serial dilutions can be performed in sterile buffer, ensuring the final concentration meets experimental requirements. Consistency in concentration is vital for reproducibility, particularly in studies involving spore germination, antimicrobial testing, or probiotic formulation.

Practical tips can streamline the resuspension process and enhance its success. For instance, pre-chilling the buffer to 4°C can reduce spore metabolism during handling, preserving their dormant state. Additionally, adding a small amount of Tween 80 (0.05%) to the buffer can help reduce surface tension and improve spore dispersion, though its use should be avoided in applications sensitive to surfactants. Finally, storing the suspension at 4°C in sterile, sealed tubes can maintain spore viability for weeks, though long-term storage at -20°C or lyophilization may be necessary for extended preservation.

In conclusion, resuspending purified *Bacillus subtilis* spores in sterile buffer or water requires careful attention to buffer selection, mixing techniques, and concentration control. By adhering to best practices and incorporating practical tips, researchers can prepare high-quality spore suspensions tailored to their specific needs. This step is foundational for a wide range of applications, from fundamental microbiology research to industrial and therapeutic uses, underscoring its importance in the broader process of spore suspension preparation.

Mastering Spore Log Reduction: Calculation Methods and Practical Tips

You may want to see also

Storage and Stability: Optimal conditions (temperature, pH, and additives) for long-term spore suspension preservation

Long-term preservation of *Bacillus subtilis* spore suspensions hinges on maintaining their viability under optimal storage conditions. Temperature is a critical factor, with refrigeration at 4°C being the gold standard for extended storage. At this temperature, metabolic activity is minimized, significantly slowing the degradation of spore integrity. However, for ultra-long-term preservation, freezing at -20°C or even -80°C in the presence of cryoprotectants like glycerol (final concentration of 10-20%) is recommended. While freezing can stress spores, glycerol acts as a protective agent, preventing ice crystal formation and membrane damage.

Research indicates that spores stored at -80°C with glycerol can retain viability for decades, making this method ideal for archival purposes.

PH plays a subtle yet important role in spore suspension stability. *B. subtilis* spores are most stable in a slightly alkaline environment, with a pH range of 7.0 to 8.5 being optimal. Deviations from this range can lead to decreased viability over time. Buffering agents like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) are commonly used to maintain pH stability, ensuring a consistent environment for spore preservation. It's crucial to avoid acidic conditions, as low pH can compromise spore coat integrity and accelerate degradation.

While pH adjustments are relatively straightforward, regular monitoring is recommended, especially for long-term storage, to ensure the buffer system remains effective.

The addition of specific additives can significantly enhance spore suspension stability. Trehalose, a disaccharide sugar, is particularly effective at protecting spores during desiccation and freezing. Its ability to replace water molecules and stabilize macromolecular structures makes it a valuable preservative. Incorporating trehalose at a concentration of 5-10% (w/v) in the spore suspension before drying or freezing can dramatically improve long-term viability. Other additives like skim milk powder (10% w/v) or peptone (1% w/v) can provide nutrients and further stabilize spores, especially during refrigeration.

Beyond temperature, pH, and additives, the choice of storage container is also important. Glass vials with airtight seals are preferred over plastic due to their inert nature and ability to prevent moisture exchange. For freeze-dried spores, vacuum-sealed ampoules offer the best protection against environmental contaminants and moisture ingress. Regardless of the container, labeling with detailed information including spore strain, preparation date, storage conditions, and any additives used is essential for proper tracking and future use. By carefully considering these factors – temperature, pH, additives, and container choice – researchers can ensure the long-term viability and stability of *Bacillus subtilis* spore suspensions for various applications.

Focal Spora N3 Price Guide: How Much Does It Cost?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A Bacillus subtilis spore suspension is commonly used in research, agriculture, and industry for applications like biofertilizers, probiotics, and biocontrol agents. Spores are highly resistant and can survive harsh conditions, making them ideal for long-term storage and application.

You will need a Bacillus subtilis culture, nutrient broth (e.g., LB broth), sterile water, a heat-resistant container, a centrifuge, and sterile filters (0.22 μm). Additionally, a microscope and malachite green stain can be used to confirm spore formation.

Spore formation (sporulation) is induced by nutrient depletion. Grow the Bacillus subtilis culture in nutrient broth until it reaches the stationary phase (typically 24–48 hours at 37°C). The cells will then initiate sporulation as nutrients become scarce.

After sporulation, centrifuge the culture to pellet the spores, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the pellet in sterile water. Repeat the washing step 2–3 times to remove debris. Finally, filter the suspension through a 0.22 μm filter to remove any remaining vegetative cells and obtain a pure spore suspension.

Store the spore suspension at 4°C for short-term use (up to a few weeks) or at -20°C or -80°C with glycerol (15–20% final concentration) for long-term storage. Glycerol acts as a cryoprotectant, preserving spore viability during freezing.