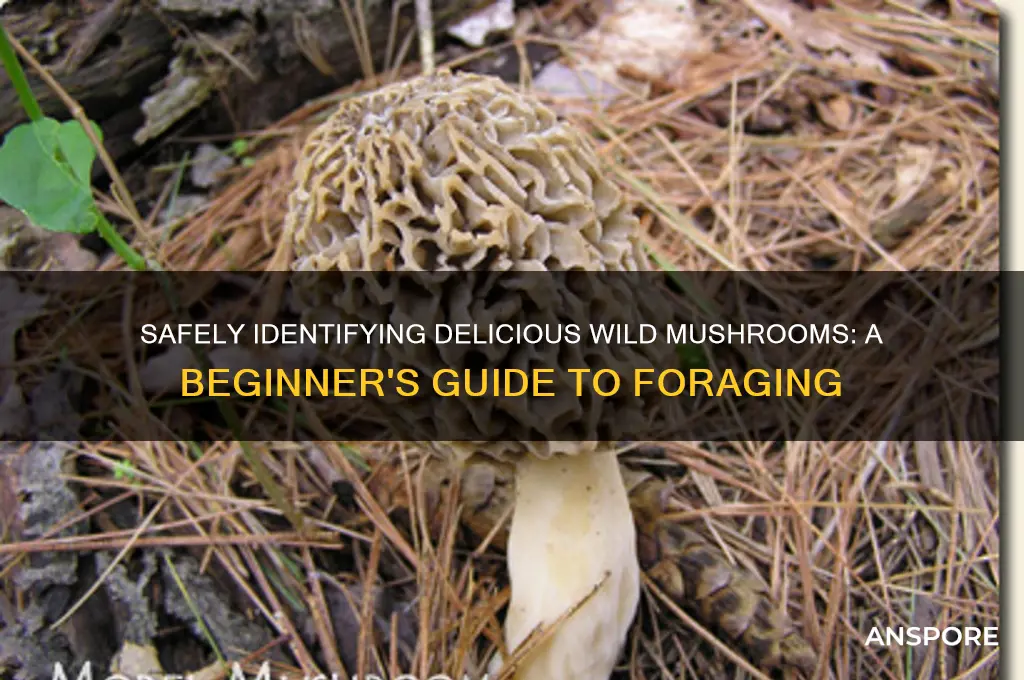

Identifying safe-to-eat wild mushrooms is a skill that requires careful observation, knowledge, and often expert guidance. While some wild mushrooms are delicious and nutritious, others can be toxic or even deadly. Key factors to consider include the mushroom’s cap shape, color, gills, stem, spore print, and habitat. Familiarizing yourself with common edible species like chanterelles, morels, and porcini is essential, as is learning to recognize dangerous look-alikes such as the Death Cap or Destroying Angel. Always cross-reference findings with reliable field guides or consult a mycologist, and never consume a wild mushroom unless you are absolutely certain of its identity. When in doubt, leave it out—safety should always come first.

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Identify Key Features: Learn spore print, gill, cap, and stem characteristics for safe mushroom identification

- Use Field Guides: Carry reliable guides to cross-reference findings and avoid toxic look-alikes

- Check Habitat: Understand where edible mushrooms grow; some thrive in specific trees or soils

- Avoid Common Toxins: Recognize poisonous types like Amanita or Galerina to prevent accidental ingestion

- Cook Before Eating: Always cook wild mushrooms to destroy potential toxins and improve digestibility

Identify Key Features: Learn spore print, gill, cap, and stem characteristics for safe mushroom identification

Identifying wild mushrooms for safe consumption requires a deep understanding of their key features, particularly the spore print, gill, cap, and stem characteristics. Spore prints are one of the most reliable methods for mushroom identification. To create a spore print, place the cap of the mushroom gill-side down on a piece of white or black paper (depending on the expected spore color) and cover it with a glass or bowl. After 24 hours, carefully remove the cap and examine the spore deposit. The color and pattern of the spores can help narrow down the mushroom species. For example, chanterelles typically produce a pale yellow to whitish spore print, while amanitas often have white spores. Always compare your findings with reliable guides to ensure accuracy.

The gill structure is another critical feature to examine. Gills are the thin, blade-like structures under the cap where spores are produced. Observe their attachment to the stem—whether they are free, adnate (broadly attached), or decurrent (extending down the stem). Also, note the gill spacing, color, and whether they have a serrated edge. For instance, edible mushrooms like oyster mushrooms have gills that are close and decurrent, while some toxic species may have crowded or forked gills. Always handle gills gently, as their appearance can change with age or damage.

The cap is perhaps the most noticeable part of a mushroom and provides essential clues for identification. Pay attention to its shape (conical, convex, flat), color, texture (smooth, scaly, slimy), and margin (curled inward, straight, or uplifted). Some edible mushrooms, such as porcini, have a distinctive brown cap with a slightly sticky texture when young. In contrast, the deadly Amanita species often have a smooth, white to brightly colored cap with distinctive warts or patches. Always consider the cap’s features in conjunction with other characteristics for accurate identification.

The stem is equally important and should be examined thoroughly. Note its length, thickness, shape (equal, enlarging, or tapering), color, and texture. Look for a ring (partial veil remnants) or a volva (cup-like structure at the base), which are often present in Amanita species and can indicate toxicity. Edible mushrooms like shiitakes typically have a smooth, even-colored stem without a volva. Additionally, check for any bruising or changes in color when the stem is damaged, as this can be a warning sign for toxic species.

Mastering these key features—spore print, gill, cap, and stem characteristics—is essential for safely identifying wild mushrooms. Always cross-reference your observations with multiple reliable sources, such as field guides or expert advice, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Remember, some toxic mushrooms closely resemble edible ones, so attention to detail is crucial. By developing these identification skills, you can confidently forage for wild mushrooms while minimizing risks.

Do Wolves Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Carnivores' Unexpected Dietary Habits

You may want to see also

Use Field Guides: Carry reliable guides to cross-reference findings and avoid toxic look-alikes

When foraging for wild mushrooms, one of the most critical tools you can carry is a reliable field guide. Field guides are essential for accurately identifying mushrooms and distinguishing edible species from toxic look-alikes. These guides provide detailed descriptions, photographs, and illustrations that help you cross-reference your findings in the field. Always choose guides written by mycologists or experienced foragers, as they offer scientifically accurate information. Popular options include *National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms* or *Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada*. Investing in a trusted guide can significantly reduce the risk of misidentification.

Using a field guide effectively requires careful observation and comparison. When you find a mushroom, note its key features such as cap shape, color, gill structure, stem characteristics, and habitat. Compare these details with the descriptions and images in your guide. Pay attention to subtle differences, as toxic mushrooms often mimic edible ones closely. For example, the deadly Amanita species can resemble harmless Agaricus mushrooms, but a field guide will highlight distinctions like the presence of a volva or ring. Always cross-reference multiple features to ensure accuracy.

Field guides also often include information on spore color, which is a crucial identification tool. To check spore color, place the mushroom cap on a piece of paper or glass overnight and observe the print left behind. Compare this color to the guide’s descriptions. While this step may require additional time, it can be a decisive factor in identification. Remember, some toxic mushrooms have spores that closely resemble those of edible species, so use this method in conjunction with other characteristics.

Another advantage of field guides is their portability and accessibility. Unlike digital resources, which may not always be available in remote areas, a physical guide can be carried anywhere. Laminated pages or waterproof editions are particularly useful for wet or muddy conditions. Additionally, many guides include regional-specific information, helping you focus on the mushrooms most likely to be found in your area. This targeted approach makes identification more efficient and less overwhelming.

Lastly, while field guides are invaluable, they should not be your only resource. Combine their use with other methods, such as consulting local mycological clubs or attending foraging workshops. However, field guides remain the cornerstone of safe mushroom identification. By carrying and using them diligently, you can enjoy the thrill of foraging while minimizing the risk of accidental poisoning. Always remember the forager’s motto: "When in doubt, throw it out."

Do Amphibians Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Their Diet and Habits

You may want to see also

Check Habitat: Understand where edible mushrooms grow; some thrive in specific trees or soils

When venturing into the world of wild mushroom foraging, understanding the habitat is crucial for identifying edible species. Different mushrooms have specific environmental preferences, and recognizing these can significantly increase your chances of finding safe and delicious varieties. For instance, many edible mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with certain trees, a phenomenon known as mycorrhizal association. Chanterelles, a highly prized edible mushroom, often grow in coniferous or beech forests, forming a mutualistic bond with the tree roots. This means that knowing the tree species in your foraging area can be a valuable clue. Look for chanterelles near spruce, fir, or oak trees, as they are commonly found in these habitats.

The type of soil is another critical factor in determining mushroom habitat. Some mushrooms prefer rich, organic soils, while others thrive in more acidic or alkaline conditions. Morels, a delicacy among foragers, often grow in areas with well-drained, loamy soil, particularly in recently burned forests or areas with decaying wood. On the other hand, the common oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) favors growing on decaying wood, especially beech or oak trees. Understanding these soil preferences can help you narrow down your search and avoid potentially toxic look-alikes.

It's essential to note that some mushrooms are highly specific about their habitat. For example, the prized truffle is a subterranean fungus that grows in symbiosis with the roots of certain trees, primarily oak, hazel, and beech. Truffle hunters often use trained animals to locate them due to their underground nature. This highlights the importance of researching and understanding the unique ecological requirements of different mushroom species.

In addition to trees and soil, consider the geographical location and climate. Certain mushrooms are more prevalent in specific regions due to the local environment. For instance, the porcini mushroom (Boletus edulis) is commonly found in Europe and North America, favoring temperate forests with acidic soil. In contrast, the enoki mushroom is native to China, Japan, and North America, growing in the wild on stumps and tree trunks.

By studying these habitat preferences, foragers can develop a keen eye for spotting edible mushrooms. It's a skill that combines knowledge of mycology, botany, and ecology, allowing you to appreciate the intricate relationships between mushrooms and their environment. Always remember that proper identification is crucial, and when in doubt, consult a local mycological society or an expert forager to ensure a safe and enjoyable mushroom-hunting experience.

Are Boletus Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Consumption

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Avoid Common Toxins: Recognize poisonous types like Amanita or Galerina to prevent accidental ingestion

When foraging for wild mushrooms, one of the most critical skills is learning to identify and avoid poisonous species. Among the most dangerous are Amanita and Galerina, which contain potent toxins that can cause severe illness or even be fatal if ingested. Amanita species, such as the "Death Cap" (*Amanita phalloides*) and the "Destroying Angel" (*Amanita bisporigera*), are responsible for the majority of mushroom-related fatalities worldwide. These mushrooms often resemble edible varieties like the button mushroom or paddy straw mushroom, making them particularly treacherous. Key features to look for in *Amanita* include a bulbous base, a ring (partial veil) on the stem, and white gills. However, relying solely on these characteristics can be risky, as some edible mushrooms share similar traits. Always cross-reference multiple identification guides and consult experts when in doubt.

Galerina mushrooms are another group to avoid, often found growing on wood or in mossy areas. They contain the same deadly amatoxins found in *Amanita* species. Galerina mushrooms are small, brown, and can easily be mistaken for edible species like *Psathyrella* or young *Armillaria*. A telltale sign of Galerina is their habitat—they are often found on decaying wood, while many edible mushrooms grow in soil. Additionally, Galerina typically has rusty-brown spores, which can be verified using a spore print. However, this requires careful handling and should not be the sole method of identification. If you are unsure about a mushroom growing on wood, it is best to leave it alone.

To avoid accidental ingestion of these toxins, always adhere to the principle of "when in doubt, throw it out." Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Beginners should focus on learning a few easily identifiable edible species, such as chanterelles, lion's mane, or morels, rather than trying to identify every mushroom they encounter. It is also crucial to avoid foraging in areas where toxic species are known to grow, such as near oak or birch trees, which are common habitats for *Amanita phalloides*.

Another important practice is to never rely on myths or folklore for identification. Common misconceptions, such as "poisonous mushrooms always taste bad" or "animals avoid toxic mushrooms," are false and dangerous. Many toxic mushrooms are odorless, taste pleasant, and are consumed by wildlife without immediate harm. Always use reliable field guides, apps, or consult mycological experts to confirm your findings.

Lastly, if you suspect you or someone else has ingested a poisonous mushroom, seek medical attention immediately. Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning, for example, may not appear for 6–24 hours after ingestion, but early treatment can be life-saving. Keep a sample of the mushroom for identification, as this can aid in diagnosis and treatment. By staying informed, cautious, and respectful of the risks, you can safely enjoy the rewarding hobby of mushroom foraging while avoiding the dangers of toxic species like *Amanita* and *Galerina*.

Avoid Portobello Mushrooms: Hidden Health Risks You Should Know

You may want to see also

Cook Before Eating: Always cook wild mushrooms to destroy potential toxins and improve digestibility

When foraging for wild mushrooms, it’s crucial to remember that even edible varieties can harbor toxins or hard-to-digest compounds in their raw state. Cooking wild mushrooms is not optional—it’s essential. Heat breaks down potentially harmful substances, such as hydrazines found in some species like the Agaricus family, which can cause gastrointestinal distress if consumed raw. Additionally, cooking improves digestibility by softening the mushroom’s tough cell walls, making nutrients more accessible to your body. Always treat wild mushrooms as raw ingredients that require preparation, never as ready-to-eat snacks.

The process of cooking also neutralizes mild toxins that might be present in otherwise edible mushrooms. For example, the common morel mushroom contains trace amounts of hydrazine compounds, which are rendered harmless by thorough cooking. Boiling, sautéing, or baking at temperatures above 140°F (60°C) for at least 10–15 minutes ensures these toxins are destroyed. Avoid consuming wild mushrooms raw, even if they are identified as edible, as raw consumption increases the risk of adverse reactions. Cooking is a simple yet critical step to ensure safety.

Another reason to cook wild mushrooms is to eliminate parasites, bacteria, and other microorganisms that may be present on their surfaces. Wild mushrooms grow in natural environments where they can come into contact with soil, insects, and other contaminants. Heat treatment effectively kills these potential pathogens, reducing the risk of foodborne illnesses. Even if you’ve thoroughly cleaned the mushrooms, cooking provides an extra layer of protection. Think of it as a necessary safeguard, similar to cooking meat or poultry.

Cooking also enhances the flavor and texture of wild mushrooms, making them more enjoyable to eat. Raw mushrooms can be tough, chewy, and bland, but cooking transforms them into tender, flavorful ingredients. Methods like sautéing in butter or olive oil, roasting, or simmering in soups and stews not only improve taste but also ensure safety. For instance, the earthy flavor of porcini mushrooms is amplified when cooked, while the delicate texture of chanterelles becomes more palatable. Cooking is both a culinary and safety practice.

Finally, cooking wild mushrooms is a universal guideline that applies regardless of your foraging expertise. Even experienced foragers and mycologists adhere to this rule because it eliminates uncertainty. Some mushrooms may resemble edible species but contain toxins that only cooking can neutralize. By always cooking wild mushrooms, you minimize the risk of accidental poisoning and ensure a safe dining experience. Remember: when in doubt, cook it out. This simple step is your best defense against potential hazards in wild mushroom consumption.

Can Rabbits Safely Eat Morel Mushrooms? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying edible wild mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. Always consult a reliable field guide or an experienced forager, and when in doubt, avoid consumption.

There are no universal signs, but some red flags include bright colors (red, white, or yellow), a bulbous base, or the presence of a ring on the stem. However, these are not foolproof indicators, so proper identification is crucial.

No, home tests like the silver spoon or garlic test are myths and unreliable for determining mushroom edibility. Always rely on accurate identification methods.

Common edible wild mushrooms include chanterelles, morels, porcini (bolete), and lion's mane. However, always verify their identity with a guide or expert before consuming.

Seek immediate medical attention. Bring a sample of the mushroom (if possible) or a detailed description to help healthcare providers identify the species and provide appropriate treatment.