Identifying edible mushrooms in Canada requires careful attention to detail and a solid understanding of local fungi species, as misidentification can lead to serious health risks. Canada’s diverse ecosystems support a wide variety of mushrooms, some of which are safe to eat, while others are toxic or even deadly. Key factors to consider include the mushroom’s physical characteristics, such as its cap shape, color, gills, stem, and spore print, as well as its habitat and seasonality. While field guides and mobile apps can be helpful tools, they should not replace expert knowledge or consultation with a mycologist. Foraging safely also involves avoiding mushrooms with certain warning signs, such as a bitter taste, unusual odors, or the presence of nearby livestock, and always cooking mushrooms before consumption to neutralize potential toxins. When in doubt, it’s best to err on the side of caution and leave the mushroom undisturbed.

Explore related products

$7.61 $8.95

What You'll Learn

- Color and Shape: Bright colors, unique shapes often indicate toxicity; plain, common shapes may be safe

- Spore Print: Check spore color; white or brown prints are common in edible varieties

- Gill Attachment: Free gills (not attached to stem) are typical in many edible mushrooms

- Smell and Taste: Mild, pleasant odors and tastes can suggest edibility, but caution is key

- Habitat and Season: Grow in specific environments and seasons; research common edible species in Canada

Color and Shape: Bright colors, unique shapes often indicate toxicity; plain, common shapes may be safe

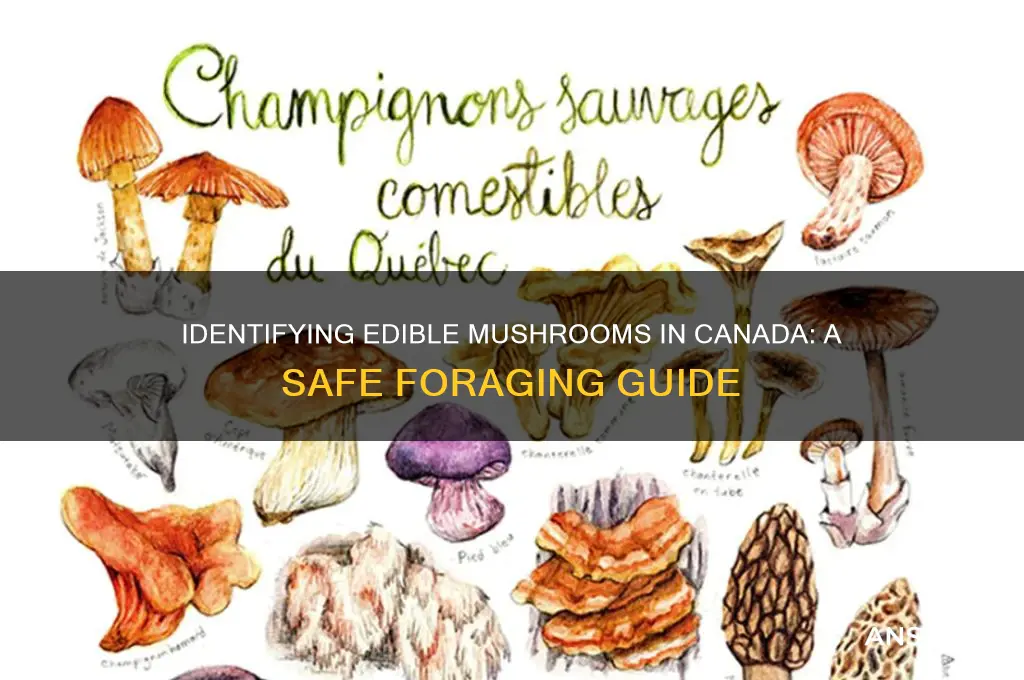

In the Canadian wilderness, a mushroom's appearance can be a critical clue to its edibility. Nature often uses color as a warning sign, and mushrooms are no exception. Bright, vivid hues like red, yellow, or green are nature's way of saying, "Proceed with caution." For instance, the fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), with its iconic red cap and white spots, is a well-known toxic species found across Canada. Its striking appearance serves as a natural deterrent, a visual alarm bell for foragers. This phenomenon, known as aposematism, is a defense mechanism where organisms advertise their toxicity through bold colors and patterns.

However, it's not just about color. The shape of a mushroom can also provide valuable insights. Unique, intricate forms may indicate a species that has evolved distinct characteristics, potentially including toxic compounds. For example, the lion's mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), with its cascading, icicle-like spines, is a safe and sought-after edible, but its unusual appearance is a reminder that not all strange shapes are dangerous. In contrast, the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), with its simple, rounded cap and plain gills, is a familiar sight in grocery stores and a safe bet for foragers.

Here's a practical tip: when in doubt, look for mushrooms with plain, brown caps and simple, gill-like structures underneath. These features are typical of many edible species in Canada, such as the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) and the shaggy mane (*Coprinus comatus*). Both have relatively subdued colors and common shapes, making them less likely to be toxic. Remember, this is a general guideline, and there are always exceptions, but it's a useful starting point for beginners.

A comparative analysis of mushroom shapes reveals that toxic species often have more complex structures. For instance, the deadly galerina (*Galerina marginata*) has a small, conical cap with a distinctive, slender stem, while the edible chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) has a more straightforward, vase-like shape with ridged undersides. This comparison highlights how nature's design can provide subtle hints about a mushroom's safety.

In summary, while color and shape are not definitive indicators of edibility, they are essential tools in a forager's arsenal. Bright colors and unusual shapes should prompt further investigation, while plain, common forms may suggest a safer option. However, always remember that proper identification requires a comprehensive approach, considering multiple factors such as habitat, odor, and spore print. Foraging for mushrooms is an art and a science, and understanding these visual cues is a crucial step in safely enjoying Canada's fungal bounty.

Can Lawn Mushrooms Get You High? Exploring the Truth

You may want to see also

Spore Print: Check spore color; white or brown prints are common in edible varieties

One of the most reliable methods to identify whether a mushroom is edible in Canada is by examining its spore print. This technique involves capturing the spores released from the mushroom’s gills or pores on a surface, revealing their color. While it may seem technical, the process is straightforward and can provide critical information. White or brown spore prints are particularly noteworthy, as they are commonly associated with edible varieties such as the Chanterelle or Porcini. However, this method is not foolproof; some toxic mushrooms also produce similar spore colors, so it should always be used in conjunction with other identification techniques.

To create a spore print, start by placing the mushroom cap gills-down on a piece of white or black paper (or glass for transparency). Cover it with a bowl to maintain humidity and leave it undisturbed for 6–24 hours. The spores will fall onto the surface, forming a distinct pattern and color. For example, the edible Oyster mushroom typically produces a white or lilac-gray spore print, while the toxic Amanita species often yield white spores that can be misleading. Always cross-reference your findings with a field guide or expert, as spore color alone is not definitive.

The analytical value of spore prints lies in their ability to narrow down mushroom identification. White and brown spores are prevalent among edible species, but exceptions exist. For instance, the edible Shaggy Mane mushroom has a black spore print, while the deadly Destroying Angel produces white spores. This highlights the importance of understanding spore color trends rather than relying on them exclusively. Additionally, spore prints can reveal unique patterns, such as the radial lines of certain boletes, which further aid in identification.

Practical tips for spore printing include using a clean, dry surface to ensure accurate color representation. If the mushroom is small or delicate, a piece of aluminum foil can be molded to support the cap. For beginners, starting with common species like the edible Lion’s Mane (yellow spores) or the toxic Galerina (rust-brown spores) can build familiarity with the process. Remember, spore printing is a tool, not a guarantee. Always avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity, and consult a mycologist or expert guide when in doubt.

In conclusion, while spore prints are a valuable step in determining edibility, they are part of a broader identification strategy. White or brown spore colors are promising indicators for edible mushrooms in Canada, but they must be interpreted carefully. Combining spore analysis with other characteristics—such as cap shape, gill attachment, and habitat—increases accuracy. Foraging safely requires patience, knowledge, and respect for the complexity of fungi. Treat spore printing as a fascinating skill that enhances your understanding of mushrooms, but never as a standalone green light for consumption.

Mushrooms in Fajitas: A Tasty Twist to Your Favorite Dish

You may want to see also

Gill Attachment: Free gills (not attached to stem) are typical in many edible mushrooms

Free gills, unattached to the stem, are a hallmark of many edible mushrooms in Canada, offering a crucial clue for foragers. This characteristic distinguishes them from certain toxic species, where gills often extend down the stem or appear to be directly connected. For instance, the beloved Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) boasts forked, free gills that run down its stem but remain distinctly separated, a feature that aligns with its edibility. Observing this detail can significantly reduce the risk of misidentification, especially when combined with other traits like color, smell, and habitat.

Analyzing gill attachment requires a methodical approach. Start by gently lifting the mushroom cap to expose the gills. If they appear to stop abruptly at the stem without any visible connection, you’re likely dealing with a free-gilled species. However, caution is paramount; free gills alone are not a definitive sign of edibility. For example, the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius) also has free gills but is highly toxic. Always cross-reference with other identifiers, such as the absence of a ring on the stem or a spicy odor, which are red flags for toxicity.

For novice foragers, practicing with common, easily identifiable species can build confidence. The Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), with its free gills and fan-like shape, is a safe starting point. Found on decaying wood, it lacks a stem in many cases, making gill attachment less of a concern. However, always carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app to verify findings. Misidentification can have severe consequences, so when in doubt, leave the mushroom untouched.

Comparatively, toxic mushrooms often exhibit gills that are adnate (attached to the stem) or decurrent (running down the stem). The Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata), for instance, has adnate gills and resembles edible species like the Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea). This similarity underscores the importance of scrutinizing gill attachment as part of a broader identification process. While free gills are a positive indicator, they should never be the sole criterion for determining edibility.

In conclusion, free gills serve as a valuable, yet not infallible, marker for edible mushrooms in Canada. By integrating this observation with other characteristics—such as habitat, spore color, and the presence of a volva or ring—foragers can make more informed decisions. Remember, mushroom hunting is as much about elimination as it is about identification. Always prioritize safety, and when uncertain, consult an expert or avoid consumption altogether.

Dialysis and Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Best Avoided?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.04 $29.99

Smell and Taste: Mild, pleasant odors and tastes can suggest edibility, but caution is key

A mushroom's aroma and flavor can offer subtle clues about its edibility, but this sensory approach demands caution and should never be the sole deciding factor. While some edible mushrooms emit mild, earthy, or nutty scents and have similarly pleasant tastes, many toxic species can also present appealing sensory profiles. For instance, the deadly Galerina marginata has a mild taste and odor, making it a dangerous look-alike to edible species like the Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea). This highlights the critical need to cross-reference smell and taste with other identification methods.

Analyzing the olfactory and gustatory characteristics requires a methodical approach. Start by gently inhaling the mushroom’s scent without touching your nose to it, as some spores can be harmful. Note whether the smell is mild, pungent, or absent. Next, if you’re confident the mushroom isn’t from a known toxic genus (like Amanita), you might cautiously taste a small portion by placing it on your tongue without swallowing. A mild, pleasant taste might suggest edibility, but a bitter, spicy, or acrid flavor is a red flag. However, even if the taste is benign, stop immediately and spit it out—some toxins act quickly, while others take hours to show symptoms.

The persuasive argument here is clear: relying solely on smell and taste is a gamble. While these senses can provide initial hints, they lack the precision needed for safe identification. For example, the edible Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) has a fruity, apricot-like aroma, but the toxic False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca) mimics this scent closely. Similarly, the edible Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) has a mild, anise-like taste, but the toxic Ivory Funnel (Clitocybe dealbata) can taste similarly benign. These overlaps underscore the importance of corroborating sensory observations with morphological features, habitat, and expert guidance.

In practice, treat smell and taste as supplementary tools, not definitive tests. Always consult field guides, apps like iNaturalist, or local mycological societies for verification. If you’re foraging with children or pets, avoid taste tests entirely, as their lower body weight makes them more susceptible to toxins. Instead, focus on teaching them visual identification cues, such as gill attachment, spore color, and cap texture. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to cultivate a respectful, informed approach to the fascinating yet perilous world of fungi.

Can Cooked Mushrooms Make You Sick? Risks and Safe Practices

You may want to see also

Habitat and Season: Grow in specific environments and seasons; research common edible species in Canada

Mushrooms don’t grow everywhere or at any time—they’re finicky about their habitat and season. In Canada, edible species like the Golden Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) thrive in coniferous and mixed forests, often forming symbiotic relationships with tree roots. Morels (*Morchella* spp.), another prized find, prefer disturbed soils, such as burned areas or recently logged forests, and emerge in spring. Knowing these preferences narrows your search and reduces the risk of mistaking a toxic look-alike for a meal.

To maximize your foraging success, align your hunts with peak seasons. In Canada, spring brings morels and oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), while late summer to fall is prime time for chanterelles and porcini (*Boletus edulis*). Coastal regions like British Columbia offer year-round opportunities due to milder climates, but inland areas like Ontario and Quebec have shorter, more concentrated seasons. Keep a foraging calendar tailored to your region, and note microclimates—south-facing slopes, for instance, warm earlier and may host mushrooms weeks before shaded areas.

Researching common edible species in Canada is non-negotiable. Start with field guides specific to your province, as distribution varies widely. For example, the Lobster Mushroom (*Hypomyces lactifluorum*), found across Canada, is a parasite that transforms other mushrooms into a seafood-like delicacy. In contrast, the Pine Mushroom (*Tricholoma magnivelare*) is a fall favorite in British Columbia but rare elsewhere. Online databases like the Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility (CBIF) and local mycological clubs provide updated distribution maps and identification tips.

Caution is paramount. Even in the right habitat and season, toxic species like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita ocreata*) or the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*) can lurk. Always cross-reference finds with multiple sources, and when in doubt, throw it out. Carry a spore print kit and a knife for detailed examination, and avoid picking near roadsides or industrial areas due to pollution risks. Remember, mushrooms absorb toxins readily—what grows in a pristine forest isn’t the same as one in a contaminated zone.

Finally, ethical foraging ensures sustainability. Harvest only what you’ll use, and cut mushrooms at the base to allow regrowth. Avoid trampling habitats, and never pick endangered species like the American Matsutake (*Tricholoma murrillianum*). By respecting these guidelines, you’ll not only safeguard your health but also preserve Canada’s fungal ecosystems for future foragers.

Can You Eat Mushrooms with a Stomach Ulcer? Expert Advice

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying edible mushrooms in Canada requires knowledge of specific characteristics. Look for mushrooms with a cap, gills, and a stem. Check for key features like color, shape, and any unique markings. Common edible species include the Chanterelle (bright yellow, forked gills) and Morel (honeycomb-like cap). Always consult a reliable field guide or expert for accurate identification.

Yes, several toxic mushrooms in Canada closely resemble edible varieties. For example, the deadly Galerina marginata looks similar to the edible Honey Mushroom. Another dangerous look-alike is the Amanita species, which can be mistaken for the edible Puffball. It's crucial to learn the distinct features of both edible and poisonous mushrooms to avoid confusion.

There are numerous resources available for mushroom enthusiasts in Canada. Consider joining local mycological societies or foraging groups, where experienced members can provide guidance. Online databases like the Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility (CBIF) offer detailed species information. Additionally, books such as "Mushrooms of Canada" by Georges M. Levesque and "Edible Wild Mushrooms of North America" by David W. Fischer are excellent references for learning about edible mushrooms and their identification.