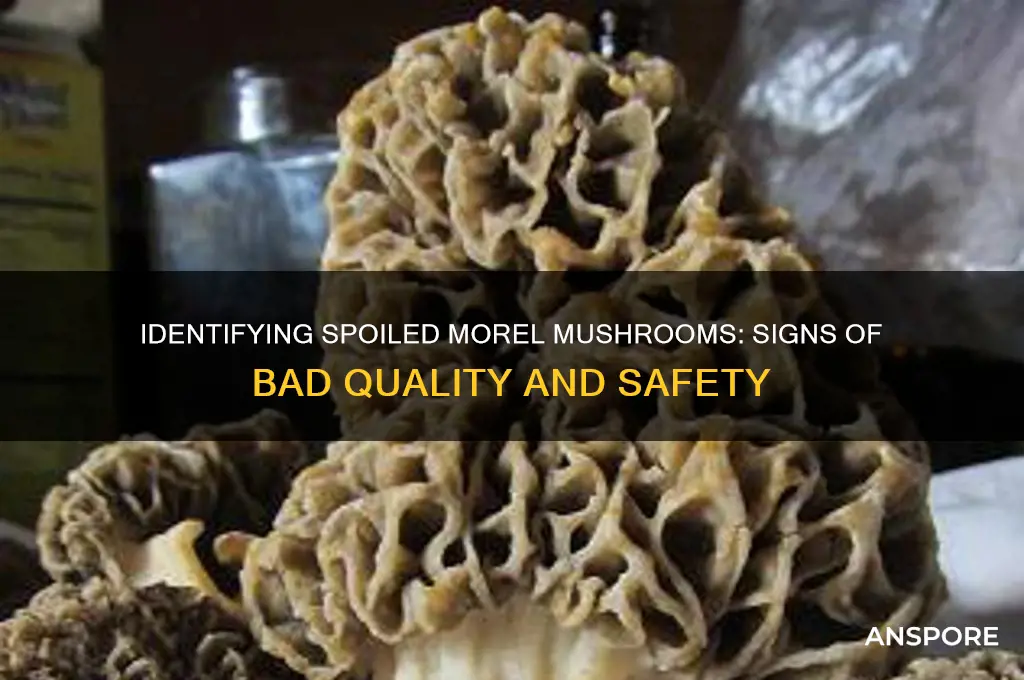

Identifying whether morel mushrooms are bad is crucial for ensuring food safety, as consuming spoiled or toxic mushrooms can lead to illness. Fresh morels should have a firm, spongy texture, a rich earthy aroma, and a vibrant, unblemished appearance. Signs of spoilage include a soft, mushy texture, discoloration, mold, or an off-putting odor. Additionally, morels that have been stored improperly or left at room temperature for too long may develop bacteria or other harmful microorganisms. Always inspect morels carefully before cooking, and when in doubt, err on the side of caution and discard them to avoid potential health risks.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Discoloration and Spots: Look for unusual colors like yellow, brown, or black spots, indicating spoilage

- Slimy Texture: Healthy morels are dry; sliminess suggests bacterial growth or decay

- Off Odor: Fresh morels smell earthy; a sour or ammonia-like odor means they’re bad

- Soft or Mushy: Firmness is key; softness or mushiness indicates overripe or spoiled mushrooms

- Insect Infestation: Check for holes, larvae, or insects, which render morels unsafe to eat

Discoloration and Spots: Look for unusual colors like yellow, brown, or black spots, indicating spoilage

Fresh morel mushrooms boast a distinctive honeycomb-like appearance with a creamy tan to golden brown hue. Any deviation from this natural palette should raise a red flag. Yellow, brown, or black spots are telltale signs of spoilage, often indicating bacterial or fungal growth. These discolorations typically start small but can quickly spread, compromising the mushroom’s integrity. If you notice such spots, especially if they’re soft or slimy to the touch, it’s best to discard the morel entirely. Even a single spoiled mushroom can contaminate others, so inspect each one carefully before use.

The presence of unusual colors isn’t just an aesthetic issue—it’s a health concern. Yellow spots, for instance, may suggest the growth of *Pseudomonas* bacteria, which can cause foodborne illness. Brown or black patches often indicate advanced decay, possibly from mold or other harmful microorganisms. While morels are prized for their earthy flavor, any off-putting odors accompanying these spots, such as a sour or ammonia-like smell, confirm spoilage. Always trust your senses; if something looks or smells wrong, it’s safer to err on the side of caution.

To minimize the risk of encountering spoiled morels, proper storage is key. Fresh morels should be consumed within 2–3 days of harvesting or purchasing. If you need to extend their shelf life, store them in a paper bag in the refrigerator, as plastic bags can trap moisture and accelerate spoilage. For longer preservation, drying or freezing morels is recommended. When rehydrating dried morels, inspect them for any discoloration that may have occurred during storage. Even preserved morels can spoil if exposed to improper conditions, so vigilance is essential.

While some foragers advocate for cutting away small discolored areas, this practice is risky. Spoilage often penetrates deeper than visible spots, and harmful toxins can spread throughout the mushroom. Additionally, morels are porous, making it difficult to ensure complete removal of contaminated tissue. Instead, focus on selecting pristine specimens and maintaining optimal storage conditions. By prioritizing freshness and safety, you’ll ensure that your morel mushrooms remain a delightful culinary treasure rather than a potential hazard.

Mushroom 13 Mechanics: How Difficulty Impacts Their Behavior

You may want to see also

Slimy Texture: Healthy morels are dry; sliminess suggests bacterial growth or decay

A slimy texture on morels is a red flag, signaling a departure from their natural, dry state. Healthy morels should feel spongy yet firm, with a honeycomb-like cap that’s free of moisture. Sliminess indicates excess water retention, often due to improper storage or advanced decay. This moisture creates an ideal environment for bacteria to thrive, compromising both the mushroom’s texture and safety. If you encounter a morel with a slick or sticky surface, it’s a clear warning to discard it immediately.

To understand why sliminess is problematic, consider the biology of morels. Their porous structure allows air circulation, keeping them dry and inhibiting bacterial growth. When exposed to high humidity or damp conditions, however, they absorb moisture, disrupting this natural defense. Bacterial colonies multiply rapidly in such environments, breaking down the mushroom’s cell walls and releasing enzymes that create a slimy film. This process not only alters the texture but also produces toxins that can cause foodborne illness if consumed.

Preventing sliminess begins with proper harvesting and storage. After foraging, gently brush off dirt and debris, but avoid washing morels—their sponge-like structure absorbs water, increasing the risk of decay. Instead, store them in a breathable container like a paper bag or mesh pouch, ensuring adequate airflow. If refrigeration is necessary, place them in the crisper drawer with a paper towel to absorb excess moisture. For long-term preservation, dehydrate morels at 125°F (52°C) until brittle, then store in an airtight container in a cool, dark place.

If you’re unsure whether a slimy morel can be salvaged, err on the side of caution. While some sources suggest trimming affected areas, the bacteria may have already penetrated deeper tissues, rendering the mushroom unsafe. Trust your senses: a healthy morel should smell earthy and clean, not sour or ammonia-like. When in doubt, discard the mushroom—the risk of illness far outweighs the desire to salvage a questionable specimen. Remember, foraging and consuming wild mushrooms requires vigilance; a single bad morel can ruin an entire meal and your health.

Driving on Mushrooms: Risks, Legalities, and Safety Concerns Explored

You may want to see also

Off Odor: Fresh morels smell earthy; a sour or ammonia-like odor means they’re bad

The aroma of a morel mushroom is its first whisper of quality. Fresh morels emit a scent that’s distinctly earthy, reminiscent of damp forest floors and rich soil. This fragrance is a hallmark of their freshness, signaling they’re ripe for cooking. However, if you detect a sour or ammonia-like odor, it’s a red flag. Such off-putting smells indicate spoilage, often due to bacterial growth or improper storage. Trust your nose—if it smells wrong, it likely is.

To identify spoilage through smell, follow a simple two-step process. First, hold the morel close to your nose and inhale gently. Note the initial scent. If it’s earthy and pleasant, proceed to the next step: sniff again after breaking the mushroom apart. Fresh morels should maintain their aroma even when fractured. A sour or chemical smell at any stage confirms they’re no longer safe to eat. This method is particularly useful for foragers or home cooks unsure of their mushrooms’ condition.

Comparing the scent of morels to other mushrooms highlights their uniqueness. While shiitakes have a smoky aroma and chanterelles smell fruity, morels’ earthy tone is unmistakable. However, this distinctiveness also makes off odors more alarming. Unlike the mild sourness that might be acceptable in aging vegetables, a sour morel is a spoiled morel. Ammonia-like smells are especially concerning, as they suggest protein breakdown, a clear sign of decay.

For practical storage tips, keep morels in a paper bag in the refrigerator, allowing airflow while absorbing excess moisture. Avoid plastic bags, which trap humidity and accelerate spoilage. Check their scent daily, especially if stored for more than 48 hours. If you’re unsure, err on the side of caution—consuming spoiled morels can lead to gastrointestinal discomfort. Remember, their aroma is both a delight and a diagnostic tool, guiding you to freshness or warning of waste.

Exploring the Effects: Is 2 Grams of Mushrooms a Substantial Dose?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Soft or Mushy: Firmness is key; softness or mushiness indicates overripe or spoiled mushrooms

Fresh morel mushrooms should feel like nature's version of a firm handshake—solid, resilient, and full of life. When you gently squeeze the base of a healthy morel, it yields slightly but retains its structure, much like a ripe avocado that’s ready to eat but not bruised. This firmness is a sign of proper hydration and freshness, indicating the mushroom was harvested at its peak. If, however, the morel feels soft or mushy, it’s a red flag. Softness suggests the mushroom has begun to break down, either from age, improper storage, or exposure to moisture. At this stage, the mushroom’s cell walls are collapsing, and its natural defenses against decay are failing. While a slightly pliable morel might still be edible, a truly mushy one is past its prime and should be discarded to avoid potential foodborne illness.

To assess firmness, use your fingertips rather than your full grip. Start by pressing the base of the mushroom, where it’s thickest, and work your way up to the cap. A fresh morel will spring back slightly under pressure, while a spoiled one will remain indented or feel spongy. Another practical tip is to compare the weight of the mushroom to its size. Fresh morels feel surprisingly light for their volume due to their hollow structure, whereas mushy morels may feel heavier, as waterlogged cells add unnecessary weight. If you’re in doubt, err on the side of caution—a single spoiled mushroom can compromise an entire batch.

The science behind mushiness lies in the mushroom’s cellular structure. Morel mushrooms are composed of a network of hyphae, which form a sponge-like matrix. When the mushroom is fresh, this matrix holds its shape, but as enzymes break down cell walls over time, the structure weakens. Moisture accelerates this process, as bacteria and mold thrive in damp environments. Proper storage—such as keeping morels in a paper bag in the refrigerator and using them within 2–3 days—can slow this degradation. However, once mushiness sets in, it’s irreversible, and the mushroom’s flavor and texture will be compromised.

Comparing morels to other mushrooms highlights the importance of firmness. For instance, button mushrooms can become slimy when spoiled, while morels turn mushy. This distinction is crucial because mushiness in morels often coincides with the growth of harmful bacteria or mold, which can be less visible than the slime on other mushroom varieties. While some foragers advocate for cutting away spoiled parts, this practice is risky with morels due to their honeycomb-like structure, which can harbor contaminants deep within the cap. The takeaway is clear: firmness isn’t just a quality marker—it’s a safety indicator.

Finally, consider the sensory experience of handling a fresh versus spoiled morel. A firm morel feels alive, its texture inviting you to cook and savor it. In contrast, a mushy morel feels like a missed opportunity, its once-vibrant structure now a cautionary tale. By prioritizing firmness, you not only ensure a better culinary outcome but also protect yourself from the risks of consuming spoiled fungi. Trust your touch—it’s one of the most reliable tools in your foraging arsenal.

Mushroom Power: Natural Anti-Inflammatory Superfood

You may want to see also

Insect Infestation: Check for holes, larvae, or insects, which render morels unsafe to eat

Morels, prized for their earthy flavor and unique honeycomb texture, can quickly turn from a gourmet delight to a health hazard if infested with insects. A single tiny hole or the presence of larvae can indicate a compromised mushroom, making it unsafe for consumption. These signs are not merely cosmetic flaws; they signal that the mushroom has been invaded by pests that can carry bacteria or toxins. Always inspect morels closely under good lighting, using a magnifying glass if necessary, to detect these subtle yet critical markers of infestation.

The process of checking for insect infestation begins with a visual examination. Look for small holes or tunnels in the mushroom’s cap or stem, which are telltale signs of insect activity. Larvae, often white or cream-colored, may be visible inside these openings or crawling on the mushroom’s surface. Even if the larvae are no longer present, their frass (excrement) or webbing can indicate past infestation. A single infested mushroom can contaminate an entire batch, so isolate and discard any suspect specimens immediately to prevent cross-contamination.

While some foragers advocate for soaking morels in saltwater to draw out insects, this method is not foolproof. Insects can burrow deep into the mushroom’s structure, remaining undetected until cooking or consumption. A more reliable approach is to carefully dissect larger morels, slicing them in half lengthwise to inspect the interior for larvae or damage. This step, though time-consuming, is essential for ensuring safety, especially when foraging in areas known for high insect activity.

The risks of consuming insect-infested morels extend beyond mere disgust. Insects can introduce harmful bacteria, such as *E. coli* or *Salmonella*, which thrive in the damp, organic environment of a mushroom. Additionally, some larvae produce toxins as a defense mechanism, which can cause gastrointestinal distress or allergic reactions. For vulnerable populations, including children, the elderly, or those with compromised immune systems, these risks are amplified, making thorough inspection a non-negotiable step in morel preparation.

In conclusion, while morels are a forager’s treasure, their delicate nature makes them susceptible to insect infestation. By adopting a meticulous inspection routine—checking for holes, larvae, or insects—you can safeguard your health and fully enjoy this seasonal delicacy. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out; no meal is worth the risk of illness.

Mushroom Interactions: Medication Risks and Side Effects

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Look for signs of spoilage such as a slimy texture, mold growth, off-putting odors, or a dark, discolored appearance. Fresh morels should be firm, dry, and have a pleasant earthy smell.

No, soft or mushy morels are likely spoiled and should be discarded. Fresh morels should have a firm, spongy texture.

While bugs in morels are common and not necessarily a sign of spoilage, thoroughly clean the mushrooms to remove them. If the mushrooms show other signs of decay, discard them.

Fresh morels last 3–5 days in the fridge. If stored properly and they still look firm, dry, and smell fresh, they’re likely safe to eat. Discard if they show any signs of spoilage.