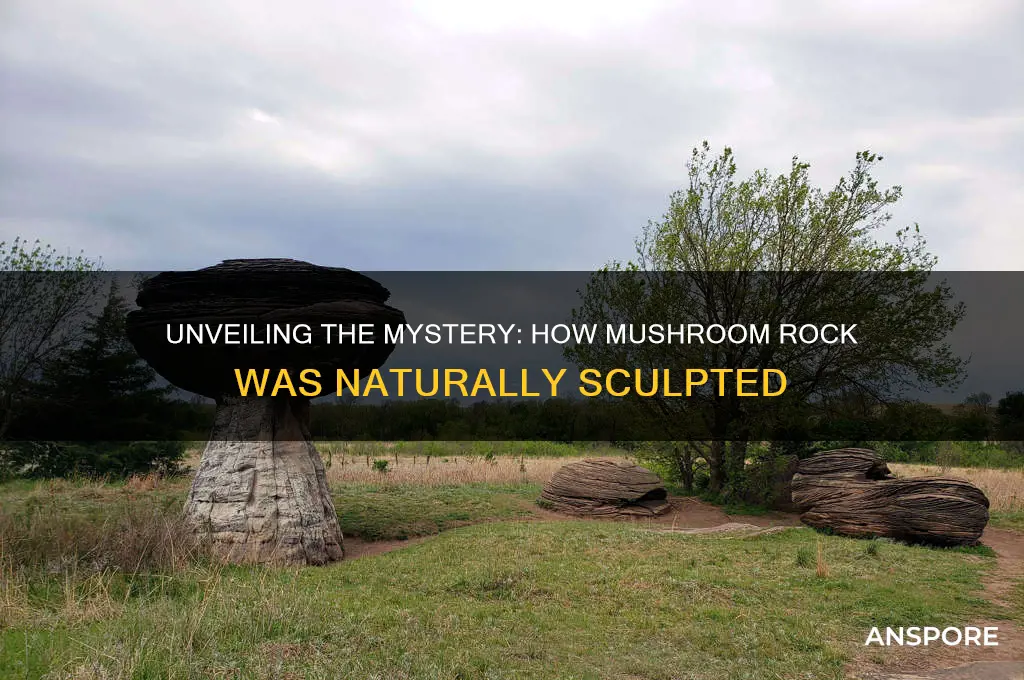

Mushroom Rock, a fascinating geological formation, is the result of differential erosion, a process where softer rock wears away more quickly than harder rock. Typically, these structures consist of a harder rock cap perched atop a softer rock pedestal. Over millions of years, wind, water, and other natural forces erode the softer material at a faster rate, leaving behind the distinctive mushroom-like shape. The cap often remains intact due to its greater resistance to weathering, while the base is gradually sculpted into a narrower column. This phenomenon is commonly observed in arid or semi-arid regions where erosion rates are high, and the rock layers vary significantly in hardness. Understanding the formation of Mushroom Rock provides valuable insights into Earth’s geological processes and the interplay between rock types and environmental forces.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formation Process | Differential erosion (softer rock beneath harder rock) |

| Primary Mechanism | Wind and water erosion |

| Rock Types Involved | Harder cap rock (e.g., sandstone) and softer base rock (e.g., limestone) |

| Geological Timeframe | Thousands to millions of years |

| Key Factors | Weathering, abrasion, and chemical erosion |

| Common Locations | Arid or semi-arid regions with exposed rock formations |

| Shape | Distinct mushroom-like structure with a wider top and narrower base |

| Examples | Mushroom Rock in Kansas, USA; Pedra do Forno in Brazil |

| Preservation Challenges | Continued erosion and human impact (e.g., vandalism, tourism) |

| Scientific Significance | Provides insights into geological processes and local climate history |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Erosion Processes: Wind, water, and ice gradually wear away softer rock, leaving harder layers intact

- Differential Erosion: Harder capstone resists erosion longer than the softer base, creating the mushroom shape

- Geological Materials: Sandstone, limestone, and granite are common materials forming mushroom rocks

- Environmental Factors: Climate, topography, and weathering rates influence mushroom rock formation over time

- Timeframe of Formation: Takes thousands to millions of years depending on erosion speed and rock type

Erosion Processes: Wind, water, and ice gradually wear away softer rock, leaving harder layers intact

Mushroom rocks, also known as pedestal rocks or rock pedestals, are fascinating geological formations that result from differential erosion, a process where softer rock is worn away more quickly than harder rock. This phenomenon is primarily driven by three key erosion agents: wind, water, and ice. Each of these elements plays a distinct role in shaping the distinctive mushroom-like structures that captivate geologists and nature enthusiasts alike.

Wind Erosion is a significant factor in arid and semi-arid regions where vegetation is sparse, and loose particles are abundant. As wind blows across the landscape, it carries sand and other abrasive particles that act like natural sandpaper. Over time, this process, known as deflation and abrasion, wears away the softer, more friable rock layers. The harder, more resistant rock layers, often composed of materials like sandstone or limestone, remain intact, forming the cap of the mushroom rock. Wind erosion is particularly effective in creating these formations in areas with consistent wind patterns and exposed rock surfaces.

Water Erosion is another critical process in the formation of mushroom rocks, especially in regions with seasonal rainfall or flowing water bodies. Raindrop impact and the flow of water can dislodge and transport sediment, gradually eroding softer rock. In areas with alternating layers of hard and soft rock, water seeps into cracks and crevices, weakening the softer layers through processes like hydration and carbonation. As the softer rock is washed away, the harder layers are left standing, often in a column or pedestal shape. This process is further accelerated by the presence of slight slopes or drainage patterns that direct water flow.

Ice Erosion, though less common in the formation of mushroom rocks, still plays a role in certain environments, particularly in colder climates. Freeze-thaw cycles, where water seeps into cracks in the rock and freezes, exerting pressure as it expands, can break apart softer rock layers. This process, known as frost wedging, gradually weakens and removes the less resistant material. The harder rock, being more resistant to this mechanical weathering, remains as a prominent feature. While ice erosion is more commonly associated with larger-scale features like valleys and fjords, it can contribute to the differential erosion that creates mushroom rocks in specific conditions.

The interplay of these erosion processes—wind, water, and ice—results in the unique morphology of mushroom rocks. The softer rock is systematically removed, while the harder layers are preserved, often in a way that creates a distinct cap-and-stem structure. This differential erosion is a testament to the varying resistance of rock types to weathering and erosion. Factors such as rock composition, grain size, and cementation play crucial roles in determining which layers will erode more quickly and which will remain as the characteristic mushroom-shaped formations.

Understanding these erosion processes not only sheds light on the formation of mushroom rocks but also highlights the dynamic nature of Earth’s surface. Over thousands to millions of years, these agents of erosion sculpt the landscape, leaving behind remarkable geological features that tell the story of the planet’s history. By studying mushroom rocks, scientists can gain insights into past climatic conditions, erosion rates, and the geological processes that continue to shape our world today.

The Best Time to Take Genius Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Differential Erosion: Harder capstone resists erosion longer than the softer base, creating the mushroom shape

Mushroom rocks, also known as pedestal rocks or rock pinnacles, are fascinating geological formations that result from a process called differential erosion. This process occurs when two distinct layers of rock with different resistance to erosion are exposed to weathering agents like wind, water, and ice. The key to understanding mushroom rock formation lies in the contrast between a harder capstone and a softer base. The capstone, typically composed of more durable materials such as sandstone, limestone, or basalt, resists erosion more effectively than the underlying softer rock, often shale, mudstone, or conglomerate.

The formation begins with the exposure of these layered rocks to the elements. Over time, water seeps into cracks and crevices in the softer base rock, gradually weakening it through processes like hydration, freeze-thaw cycles, and chemical weathering. As the base erodes, it does so at a faster rate than the harder capstone, which remains relatively intact. This disparity in erosion rates creates a distinctive shape where the capstone appears to "float" above the narrowing base, resembling a mushroom.

Wind and water play crucial roles in accelerating differential erosion. Wind-driven sand acts like sandpaper, abrading the softer base more quickly than the harder capstone. Similarly, flowing water carries sediment that preferentially erodes the base, leaving the capstone protected. The capstone’s resistance to erosion is further enhanced by its composition and structure, which may include cementing minerals or a denser grain arrangement that slows down weathering processes.

As erosion progresses, the base continues to narrow, while the capstone remains relatively unchanged in size. This creates a visually striking formation where the cap appears disproportionately large compared to the slender pedestal beneath it. The process is gradual, often taking thousands of years, and the resulting mushroom rocks serve as natural monuments to the relentless forces of erosion.

In summary, differential erosion is the primary mechanism behind mushroom rock formation. The harder capstone resists erosion longer than the softer base, leading to the characteristic mushroom shape. This process highlights the interplay between rock composition, weathering agents, and time, showcasing how nature sculpts landscapes through selective erosion. Understanding differential erosion not only explains the origin of mushroom rocks but also provides insights into broader geological processes shaping Earth’s surface.

Instantly Wake Mushrooms in Agrabah: 3-Second Secret Technique Revealed

You may want to see also

Geological Materials: Sandstone, limestone, and granite are common materials forming mushroom rocks

Mushroom rocks, also known as pedestal rocks or rock pedestals, are fascinating geological formations that result from specific weathering and erosion processes. The materials that commonly form these structures—sandstone, limestone, and granite—play a crucial role in their development. Each of these rocks has unique properties that influence how they resist or succumb to the forces of nature, ultimately shaping the distinctive mushroom-like forms.

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed of sand-sized grains cemented together, often by minerals like silica or calcium carbonate. Its layered structure makes it susceptible to differential erosion, where harder layers resist weathering more than softer ones. In the formation of mushroom rocks, sandstone typically acts as the cap. The harder, more resistant layer remains intact while the softer layers beneath are eroded away by wind, water, or ice. This process, known as exfoliation or spheroidal weathering, gradually creates the pedestal-like stem, giving the rock its mushroom shape. Sandstone’s relatively high porosity and permeability also allow water to penetrate and weaken the rock, accelerating erosion in the lower sections.

Limestone, another sedimentary rock, is primarily composed of calcium carbonate, often from the remains of marine organisms. It is more soluble than sandstone, making it highly susceptible to chemical weathering, particularly in areas with acidic rainwater. In mushroom rock formation, limestone often forms the stem due to its tendency to dissolve and erode more uniformly. The cap may consist of a harder, less soluble layer, such as a silica-rich crust or a more resistant limestone variant. Over time, the chemical breakdown of limestone creates undercuts and overhangs, contributing to the mushroom-like appearance. Karst landscapes, where limestone is prevalent, frequently feature such formations due to the rock’s reactivity with water.

Granite, an igneous rock, is composed of minerals like quartz, feldspar, and mica, making it extremely hard and resistant to weathering. However, granite is prone to exfoliation, where outer layers peel away due to the release of pressure as the rock is exposed to the surface. In mushroom rock formations, granite typically forms both the cap and the stem, with the cap being a more resistant portion of the rock. The stem is created as weaker layers or joints in the granite erode away, leaving behind a narrower base. This process is slow but effective, as granite’s durability ensures that the cap remains intact while the stem is gradually shaped by physical weathering.

The formation of mushroom rocks from these materials is a testament to the interplay of rock composition, environmental conditions, and geological processes. Sandstone’s layered structure, limestone’s solubility, and granite’s hardness each contribute uniquely to the creation of these striking formations. Understanding the properties of these geological materials provides insight into the mechanisms behind mushroom rock formation and highlights the role of differential erosion in sculpting Earth’s landscapes. By studying these rocks, geologists can unravel the history of weathering and erosion in a given area, offering a window into the planet’s past.

Cream of Mushroom and Noodles: A Nutritious Dinner Option?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: Climate, topography, and weathering rates influence mushroom rock formation over time

Mushroom rock formations are captivating geological features shaped by a combination of environmental factors, primarily climate, topography, and weathering rates. These elements interact over extended periods to create the distinctive mushroom-like structures that intrigue geologists and nature enthusiasts alike. Understanding the role of these environmental factors provides insight into the processes that sculpt such unique landscapes.

Climate plays a pivotal role in mushroom rock formation, as it dictates the types of weathering processes that dominate a region. In arid or semi-arid climates, where precipitation is limited, physical weathering, such as thermal expansion and contraction, becomes the primary force. Daily temperature fluctuations cause the outer layers of rocks to expand and contract, leading to the gradual exfoliation of surface material. Over time, this process creates a pedestal-like base, while the harder, more resistant cap remains relatively intact, forming the mushroom shape. Conversely, in humid climates, chemical weathering, such as dissolution and hydrolysis, accelerates the breakdown of rock material. However, the formation of mushroom rocks is less common in such environments due to the rapid erosion of both the cap and the stem.

Topography further influences mushroom rock formation by determining how rocks are exposed to weathering agents. Rocks situated on slopes or elevated terrains are more susceptible to wind erosion and water runoff, which selectively remove softer materials. The orientation of rock layers, known as stratification, also affects the formation process. Horizontal or gently dipping layers often provide the structural integrity needed for the cap to withstand erosion, while the underlying layers erode more rapidly, forming the stem. Additionally, areas with sparse vegetation allow for greater exposure to weathering agents, facilitating the development of mushroom rocks.

Weathering rates are a critical factor in the formation of mushroom rocks, as they dictate the pace at which the stem and cap differentiate. Differential weathering occurs when varying rock types or layers erode at different rates. For instance, if a harder rock layer overlies a softer one, the softer layer will erode more quickly, leaving the harder layer as the cap. The rate of weathering is influenced by the rock’s mineral composition, grain size, and porosity. Rocks with higher resistance to weathering, such as quartz or sandstone, are more likely to form the cap, while less resistant materials, like shale or mudstone, form the stem. Over thousands to millions of years, this differential weathering carves out the characteristic mushroom shape.

In summary, the formation of mushroom rocks is a complex interplay of climate, topography, and weathering rates. Arid climates and specific topographic conditions enhance physical weathering, while differential weathering rates ensure the cap remains intact as the stem erodes. These environmental factors collectively shape the landscape, creating the striking mushroom rock formations observed in various parts of the world. By studying these processes, scientists can better understand the geological history and environmental conditions that have shaped Earth’s surface over millennia.

Mushrooms for Menstrual Cramps: Natural Relief or Myth?

You may want to see also

Timeframe of Formation: Takes thousands to millions of years depending on erosion speed and rock type

The formation of mushroom rocks, characterized by their distinctive cap-and-stem structure, is a geological process that unfolds over vast timescales, ranging from thousands to millions of years. This timeframe is primarily dictated by the interplay between erosion speed and the type of rock involved. Softer rocks, such as sandstone or limestone, erode more quickly under the influence of wind, water, and chemical weathering, leading to faster formation of mushroom shapes. Harder rocks, like granite, resist erosion more effectively, resulting in a much slower transformation process. Understanding this variability is crucial to appreciating the patience required by nature to sculpt these unique formations.

Erosion speed plays a pivotal role in determining how long it takes for a mushroom rock to form. In arid environments, where wind abrasion is the dominant erosive force, the process can still take thousands of years, as wind gradually wears away the base of the rock faster than the top. In contrast, humid environments with abundant water flow can accelerate erosion through processes like rain splash, stream abrasion, and chemical weathering. For instance, in areas with frequent rainfall, the softer base of a rock may erode within a few thousand years, while the harder cap remains relatively intact, creating the mushroom shape. Thus, the local climate significantly influences the overall timeframe of formation.

The type of rock is another critical factor in the formation timeline. Sedimentary rocks, composed of layered particles, often exhibit differential erosion rates due to variations in hardness between layers. This can lead to the rapid development of mushroom shapes within tens of thousands of years. Igneous and metamorphic rocks, however, are typically more uniform in composition and hardness, slowing the erosion process considerably. For example, a granite boulder might take millions of years to develop a mushroom shape due to its resistance to weathering. This highlights the importance of rock type in dictating the pace of geological transformation.

Chemical weathering also contributes to the formation of mushroom rocks, further extending the timeframe in certain conditions. In acidic environments, such as areas with high rainfall and acidic soil, chemical reactions can dissolve minerals in the rock more rapidly, hastening the erosion of the base. Conversely, in alkaline environments, chemical weathering occurs at a slower pace, prolonging the formation process. This interplay between physical and chemical erosion ensures that the creation of mushroom rocks is a complex, time-dependent phenomenon.

Ultimately, the formation of mushroom rocks is a testament to the relentless forces of nature operating over immense periods. Whether it takes thousands or millions of years, the process is a delicate balance of erosion speed and rock type, shaped by environmental factors like climate and chemistry. Observing these formations offers a glimpse into Earth’s geological history, reminding us of the slow, steady work of natural processes in sculpting the landscape. Each mushroom rock, therefore, is not just a curious geological feature but a chronicle of time itself.

Mushrooms: Unveiling the Secrets of Their Movements

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom rocks are formed through a geological process called differential erosion, where harder rock layers protect softer layers beneath, creating a mushroom-like shape.

Mushroom rocks are usually formed from sedimentary rocks like sandstone or limestone, where the cap is made of harder, more resistant material, and the stem is softer.

Mushroom rocks are often found in arid or semi-arid regions where wind and water erosion are prevalent, such as deserts or badlands.

The formation of a mushroom rock can take thousands to millions of years, depending on the rate of erosion and the hardness of the rock layers involved.