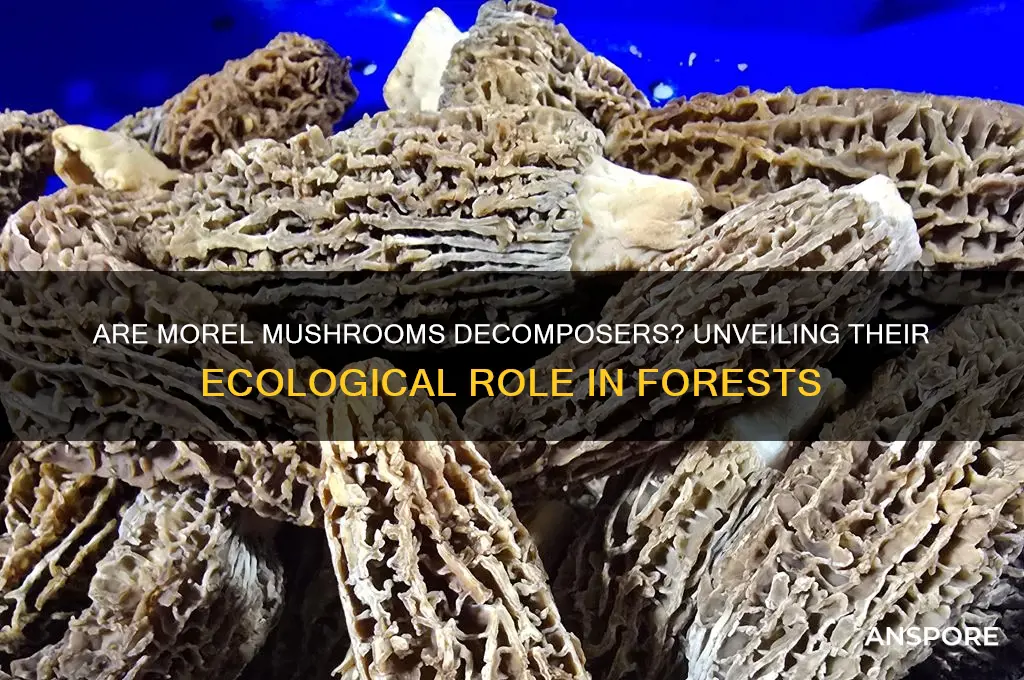

Morel mushrooms, prized for their unique honeycomb appearance and rich flavor, are often categorized as decomposers due to their ecological role in breaking down organic matter. These fungi thrive in forest ecosystems, where they form symbiotic relationships with trees, aiding in nutrient cycling by decomposing dead plant material and recycling essential elements back into the soil. While morels are primarily known as mycorrhizal fungi, which form mutualistic associations with plant roots, their ability to break down complex organic compounds also aligns with the characteristics of decomposers. This dual role highlights the complexity of morel mushrooms in their contribution to both nutrient uptake for living plants and the decomposition of dead organic matter, making them a fascinating subject in the study of fungal ecology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ecological Role | Decomposer (Saprotroph) |

| Feeding Mechanism | Breaks down dead organic matter (wood, leaves, plant debris) |

| Enzymes Produced | Secretes enzymes to decompose complex organic compounds (e.g., cellulose, lignin) |

| Nutrient Absorption | Absorbs nutrients from decomposed organic material |

| Mycelium Function | Mycelium network facilitates decomposition and nutrient cycling |

| Habitat | Found in forests, woodlands, and areas with abundant dead plant material |

| Symbiotic Relationships | Can form mycorrhizal associations with living trees (dual role as decomposer and symbiont) |

| Spores | Produces spores for reproduction, not directly involved in decomposition |

| Decomposition Rate | Contributes to slow decomposition of woody and tough plant material |

| Ecosystem Contribution | Plays a key role in nutrient recycling and soil health |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Morel's Ecological Role: Do morels break down organic matter like typical decomposers

- Mycorrhizal Relationship: How does morel's symbiotic association affect its decomposer status

- Nutrient Cycling: Do morels contribute to nutrient recycling in ecosystems

- Saprotrophic vs. Mycorrhizal: Are morels primarily decomposers or mutualistic fungi

- Decomposition Process: Do morels directly decompose dead plant material

Morel's Ecological Role: Do morels break down organic matter like typical decomposers?

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and earthy aroma, are prized by foragers and chefs alike. But their ecological role is less celebrated. Unlike typical decomposers such as bacteria and saprotrophic fungi, morels do not directly break down dead organic matter into simpler compounds. Instead, they form symbiotic relationships with living trees, primarily through mycorrhizal associations. In these partnerships, morels exchange nutrients with their hosts, absorbing sugars from the tree while providing essential minerals like phosphorus and nitrogen in return. This mutualism highlights a unique ecological niche: morels are not decomposers but facilitators of nutrient cycling in living ecosystems.

To understand why morels aren’t decomposers, consider their life cycle and habitat. Morels thrive in forests, often appearing in the spring after disturbances like wildfires or logging. Their mycelium networks persist underground, forming connections with tree roots rather than decaying wood or leaf litter. Decomposers, by contrast, secrete enzymes to break down complex organic materials into inorganic compounds, releasing nutrients back into the soil. Morels lack this enzymatic machinery, relying instead on their hosts for carbon. This distinction is crucial for ecologists and foragers alike, as it explains why morels are found near living trees rather than in areas of abundant dead matter.

From a practical standpoint, this ecological role has implications for cultivation and conservation. Attempts to grow morels commercially often fail because replicating their symbiotic relationship with trees is challenging. Foragers should note that morels’ presence indicates a healthy forest ecosystem, not a decomposing one. To support morel populations, focus on preserving mature trees and minimizing soil disturbance. Avoid overharvesting, as morels play a vital role in tree health and forest resilience. Understanding their non-decomposer status can guide sustainable practices and deepen appreciation for their ecological significance.

Comparatively, morels’ ecological role contrasts sharply with that of decomposer fungi like *Coprinus comatus* (the shaggy mane) or *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms). These species actively break down wood, leaves, and other organic debris, accelerating decomposition and nutrient release. Morels, however, operate within a living system, enhancing nutrient uptake for their tree partners. This difference underscores the diversity of fungal strategies in ecosystems. While decomposers are essential for recycling dead matter, morels contribute by strengthening the health and productivity of living organisms, showcasing the multifaceted roles fungi play in nature.

In conclusion, morels are not decomposers but rather symbiotic partners in forest ecosystems. Their reliance on mycorrhizal relationships with living trees distinguishes them from fungi that break down dead organic matter. This unique ecological role has practical implications for cultivation, foraging, and conservation. By recognizing morels’ contribution to nutrient cycling in living systems, we can better appreciate their value and work to protect the habitats that sustain them. Understanding this distinction enriches our knowledge of fungal ecology and highlights the intricate connections within forest ecosystems.

Are All Mushroom Coffees Equal? Exploring Varieties and Benefits

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal Relationship: How does morel's symbiotic association affect its decomposer status?

Morels, those prized springtime fungi, are not your typical decomposers. While many mushrooms break down dead organic matter, morels form a unique partnership with living trees through a mycorrhizal relationship. This symbiotic association challenges the straightforward label of "decomposer."

Instead of relying solely on decaying material, morels act as intermediaries, connecting with tree roots to exchange nutrients.

Imagine a bustling underground marketplace. The tree provides carbohydrates, products of photosynthesis, to the morel. In return, the morel's extensive network of filaments, called hyphae, acts as an extension of the tree's root system, efficiently absorbing water and minerals from the soil that the tree might struggle to reach on its own. This mutually beneficial exchange highlights the complexity of fungal ecology, blurring the lines between decomposer and collaborator.

Unlike saprotrophic fungi that directly decompose organic matter, morels rely on their living partners for sustenance, making them more akin to facilitators of nutrient cycling than primary decomposers.

This mycorrhizal relationship has profound implications for both the morel and its host tree. The morel gains access to a reliable food source, while the tree benefits from enhanced nutrient uptake and potentially increased resistance to pathogens. This interdependence underscores the intricate web of life beneath our feet, where fungi play a crucial role in forest health and ecosystem functioning. Understanding this symbiotic dance is essential for appreciating the true nature of morels and their place in the natural world.

Shiitake Mushrooms: Safe or Unsafe During Pregnancy?

You may want to see also

Nutrient Cycling: Do morels contribute to nutrient recycling in ecosystems?

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and elusive nature, are more than just a forager’s prize—they are key players in nutrient cycling within forest ecosystems. Unlike decomposers that break down dead organic matter directly, morels form symbiotic relationships with living trees, primarily through mycorrhizal associations. In this partnership, morels extend their filamentous hyphae into the soil, increasing the tree’s access to nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. In exchange, the tree provides carbohydrates to the fungus. This process not only supports tree health but also redistributes nutrients throughout the ecosystem, ensuring their availability for other organisms.

Consider the lifecycle of a morel: it thrives in disturbed environments, such as burned forests or recently logged areas. Here, the fungus accelerates nutrient release from decaying wood and organic debris, though it does not decompose material itself. Instead, morels act as facilitators, enhancing the breakdown process by partnering with bacteria and other fungi. For instance, their hyphae can penetrate wood more efficiently than many decomposers, making nutrients trapped in lignin and cellulose accessible to the broader ecosystem. This indirect contribution to decomposition is a critical yet often overlooked role in nutrient recycling.

To understand morels’ impact, imagine a forest floor after a wildfire. Nutrients locked in dead trees and ash are inaccessible to most plants. Morels, however, can mobilize these nutrients, forming mycorrhizal networks that connect surviving trees and emerging seedlings. This process not only aids forest recovery but also prevents nutrient loss through leaching or runoff. Studies show that morel-dominated ecosystems exhibit higher soil fertility and faster regeneration rates compared to areas lacking such fungi. For forest managers, encouraging morel growth post-disturbance could be a practical strategy to restore nutrient cycles.

While morels are not decomposers in the traditional sense, their role in nutrient cycling is undeniable. By bridging the gap between organic matter and living organisms, they ensure that essential elements remain in circulation. Foragers and conservationists alike should recognize this function: harvesting morels sustainably, avoiding damage to their mycelial networks, and preserving their habitats are vital steps to maintain healthy ecosystems. In the delicate balance of nature, morels are not just a culinary treasure but a linchpin of ecological resilience.

Mushrooms and Breastfeeding: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Saprotrophic vs. Mycorrhizal: Are morels primarily decomposers or mutualistic fungi?

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and elusive nature, are prized by foragers and chefs alike. But their ecological role is less celebrated yet equally fascinating. To understand whether morels are primarily decomposers or mutualistic fungi, we must delve into the dual worlds of saprotrophic and mycorrhizal fungi. Saprotrophs break down dead organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem, while mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plants, enhancing nutrient uptake in exchange for carbohydrates. Morels, it turns out, straddle both roles, though their primary function leans toward mutualism.

Consider the life cycle of a morel. Unlike saprotrophic fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, which thrive on decaying wood or leaves, morels rarely decompose dead material directly. Instead, they form intricate underground networks called mycorrhizae, primarily with trees such as ash, elm, and poplar. Through these partnerships, morels help trees absorb phosphorus, nitrogen, and other essential nutrients from the soil, while the trees provide the fungi with sugars produced via photosynthesis. This mutualistic relationship is so critical that morels often fail to fruit in the absence of their host trees, underscoring their dependence on this symbiosis.

However, morels are not strictly mycorrhizal. Recent studies suggest they may exhibit saprotrophic tendencies under specific conditions, particularly in nutrient-poor soils. For instance, morels have been observed breaking down complex organic compounds like lignin and cellulose, typically the domain of decomposer fungi. This dual capability allows morels to adapt to varying environmental conditions, though their primary ecological role remains rooted in mutualism. For foragers, this means morels are most commonly found in healthy, living forests rather than decaying woodlots.

Practical implications of this distinction are significant. If you’re cultivating morels, focus on creating a mycorrhizal-friendly environment: plant compatible tree species, maintain soil pH between 6.0 and 7.5, and avoid excessive nitrogen fertilization, which can disrupt the symbiosis. Foraging efforts should target areas with recent disturbances, such as wildfires or logging, where morels often fruit prolifically due to their ability to colonize regenerating forests. Understanding their dual nature also highlights the importance of preserving diverse ecosystems, as morels’ survival depends on both their tree partners and their occasional saprotrophic flexibility.

In the debate of saprotrophic versus mycorrhizal, morels defy simple categorization. They are not primarily decomposers but rather mutualistic fungi with a saprotrophic backup plan. This duality makes them ecological chameleons, thriving in dynamic environments and rewarding those who understand their complex relationships. Whether you’re a forager, gardener, or ecologist, recognizing morels’ dual roles enriches both your knowledge and your appreciation of these enigmatic fungi.

Are Mushrooms Legal in Washington? Decriminalization Status Explained

You may want to see also

Decomposition Process: Do morels directly decompose dead plant material?

Morels, those prized fungi of spring foraging, are often lumped into the broad category of decomposers. But do they directly break down dead plant material like other mushrooms? The answer lies in understanding their unique ecological role. Unlike saprotrophic fungi that secrete enzymes to decompose organic matter, morels are mycorrhizal. This means they form symbiotic relationships with living tree roots, exchanging nutrients for carbohydrates. While they don’t directly decompose dead plants, their presence in forest ecosystems contributes to overall decomposition indirectly by supporting the health of their host trees.

To grasp this process, consider the steps involved in morel-tree symbiosis. First, morel mycelium intertwines with tree roots, creating a network that enhances the tree’s ability to absorb water and minerals. In return, the tree provides sugars produced through photosynthesis. This mutualism strengthens the tree, allowing it to thrive and contribute more organic matter to the soil when leaves or branches eventually fall. Thus, while morels aren’t decomposers themselves, their role in sustaining trees indirectly supports the decomposition cycle.

A cautionary note: mistaking morels for decomposers can lead to misconceptions about their cultivation. Foragers and gardeners often assume that adding dead plant material will encourage morel growth, but this approach is ineffective. Instead, creating a habitat with compatible living trees, such as ash or elm, and maintaining a pH between 6.0 and 7.5 is key. Practical tips include leaving leaf litter undisturbed and avoiding soil compaction to foster the mycorrhizal relationship.

Comparatively, saprotrophic mushrooms like oyster or shiitake directly decompose wood and plant debris, making them ideal for recycling organic waste. Morels, however, are specialists in symbiosis, thriving in specific forest conditions. This distinction highlights the diversity of fungal roles in ecosystems and underscores why morels are not decomposers in the traditional sense.

In conclusion, while morels don’t directly decompose dead plant material, their mycorrhizal partnerships with trees play a vital role in forest health and nutrient cycling. Understanding this nuance not only deepens appreciation for these fungi but also guides effective foraging and cultivation practices. Next time you spot a morel, remember: it’s not breaking down the forest floor, but it’s certainly helping it flourish.

Mushroom Pills: A Natural Health Revolution?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, morel mushrooms are decomposers. They break down organic matter, such as dead plant material, in their environment to obtain nutrients.

Morel mushrooms secrete enzymes that break down complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin into simpler compounds, which they then absorb for growth and energy.

While morel mushrooms primarily act as decomposers, they also form symbiotic relationships with trees, helping them absorb nutrients in exchange for carbohydrates, making them both decomposers and mycorrhizal partners.