The question Is a spore sperm? arises from a misunderstanding of biological terms and their functions. Spores and sperm are both reproductive structures, but they belong to entirely different organisms and serve distinct purposes. Spores are typically produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria as a means of asexual reproduction or dispersal, allowing them to survive harsh conditions and colonize new environments. In contrast, sperm is a male reproductive cell found in animals and some plants, specifically designed to fertilize a female egg during sexual reproduction. While both spores and sperm play roles in reproduction, they are fundamentally different in origin, structure, and function, making the comparison inaccurate.

What You'll Learn

- Spore vs. Sperm: Definitions - Spores are reproductive cells of plants/fungi; sperm are male reproductive cells of animals

- Reproduction Methods - Spores reproduce asexually; sperm require fusion with egg for sexual reproduction

- Structure Differences - Spores are single-celled and hardy; sperm are motile with a tail

- Environmental Roles - Spores survive harsh conditions; sperm are short-lived and environment-sensitive

- Organism Types - Spores in plants/fungi; sperm in animals, highlighting distinct biological kingdoms

Spore vs. Sperm: Definitions - Spores are reproductive cells of plants/fungi; sperm are male reproductive cells of animals

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive cells, serve distinct purposes in the biological world. Spores are the resilient, often dormant cells produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria to survive harsh conditions and disperse to new environments. They are not directly involved in fertilization but rather in propagation and survival. Sperm, on the other hand, are specialized male gametes in animals, designed to fertilize female eggs, ensuring the continuation of a species through sexual reproduction. Understanding this fundamental difference is key to grasping the diversity of reproductive strategies in nature.

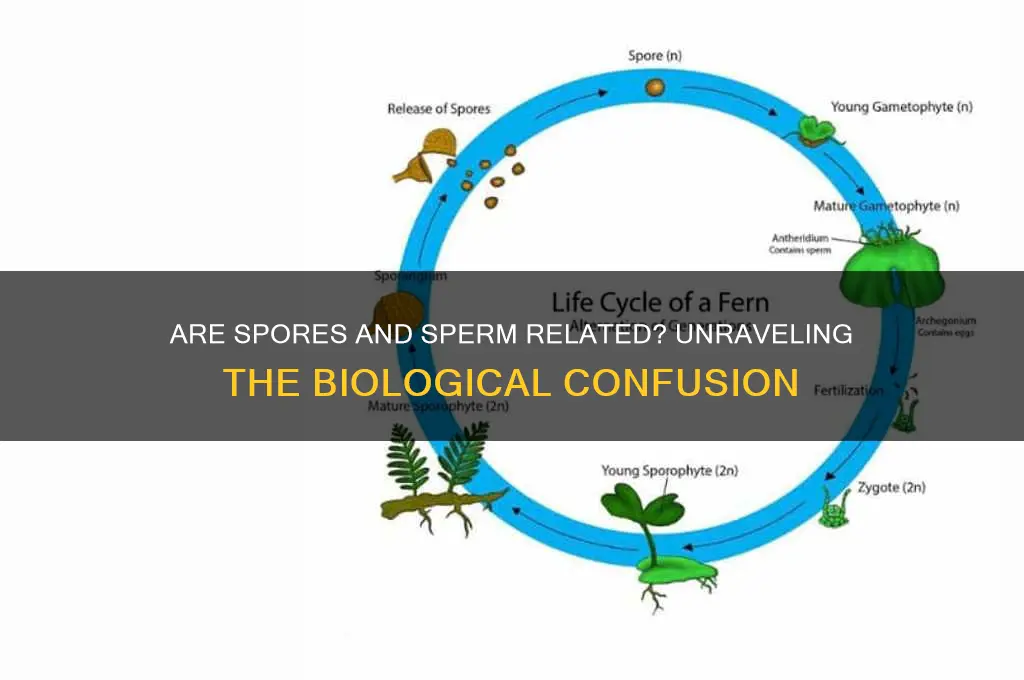

Consider the lifecycle of a fern versus that of a human. Ferns release spores that grow into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm. These sperm require water to swim to the egg, a process entirely dependent on external conditions. Humans, however, rely on sperm cells that are motile and actively seek out the egg within the reproductive tract. While both processes achieve reproduction, the mechanisms and environments in which they operate are vastly different. This contrast highlights the adaptability of life forms to their respective habitats.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between spores and sperm is crucial in fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, farmers use spore-based fungicides to combat plant diseases, while fertility clinics analyze sperm quality to assist in human reproduction. Knowing the unique roles of these cells allows for targeted interventions. For example, understanding spore dispersal helps in managing invasive fungal species, while optimizing sperm health involves factors like diet, age, and lifestyle—men over 35, for instance, may experience reduced sperm motility, necessitating lifestyle adjustments or medical intervention.

The comparison also underscores the elegance of evolution. Spores exemplify nature’s solution to survival in unpredictable environments, while sperm illustrate the precision required for complex multicellular life. This duality reflects the balance between resilience and specialization in the natural world. By studying these cells, scientists gain insights into biodiversity, ecosystem dynamics, and even potential applications in biotechnology, such as spore-inspired drug delivery systems or sperm-based diagnostics for reproductive health.

In essence, while spores and sperm share the common goal of reproduction, their structures, functions, and contexts diverge dramatically. Spores are the hardy pioneers of plant and fungal kingdoms, ensuring continuity through adversity, whereas sperm are the agile messengers of animal reproduction, driving genetic diversity. Recognizing these distinctions not only enriches our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications across disciplines, from conservation to medicine.

Does Basic G Effectively Kill Spores? A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Reproduction Methods - Spores reproduce asexually; sperm require fusion with egg for sexual reproduction

Spores and sperm represent fundamentally different strategies in the biological imperative to reproduce. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are single-celled reproductive units capable of developing into a new organism without fertilization. This asexual method ensures rapid proliferation under favorable conditions, as seen in the dispersal of fern spores or the resilience of bacterial endospores. In contrast, sperm, the male gametes in animals and certain plants, are specialized cells that must fuse with a female egg to initiate sexual reproduction. This fusion, or fertilization, combines genetic material from two parents, fostering genetic diversity and adaptability in offspring.

Consider the lifecycle of a mushroom. After releasing spores into the environment, each spore can germinate independently, growing into a new fungal organism without a partner. This efficiency allows fungi to colonize diverse habitats swiftly. Conversely, in humans, sperm must traverse the female reproductive tract to reach and penetrate an egg. This journey, though fraught with challenges, culminates in the formation of a zygote, the first cell of a genetically unique individual. The energy investment in sperm production and the complexity of fertilization underscore the trade-offs between asexual and sexual reproduction.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these mechanisms has tangible applications. In agriculture, spore-based reproduction in crops like wheat or rice can be manipulated to enhance yield through selective breeding. For instance, treating seeds with specific fungicides (e.g., 0.5% carbendazim solution) can protect spores from pathogens, ensuring healthier germination. In contrast, assisted reproductive technologies (ART) in humans, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), rely on optimizing sperm quality and viability. Sperm concentration above 15 million/mL and motility over 40% are benchmarks for successful fertilization in IVF procedures.

The distinction between spores and sperm also highlights evolutionary adaptations to environmental pressures. Spores, often resistant to extreme conditions, enable organisms to survive dormancy during unfavorable periods, as seen in bacterial spores enduring temperatures up to 100°C. Sperm, however, are short-lived and require a supportive environment, reflecting their role in immediate reproduction rather than long-term survival. This divergence illustrates how reproductive strategies align with ecological niches, whether through the resilience of asexual spores or the genetic innovation of sexual reproduction.

In educational contexts, teaching these concepts can engage students through hands-on activities. For younger learners (ages 8–12), observing mold spores grow on bread under different conditions (e.g., moist vs. dry) demonstrates asexual reproduction. For older students (ages 13–18), analyzing sperm motility under a microscope after exposing samples to varying temperatures (20°C vs. 37°C) illustrates the sensitivity of sexual reproduction. Such experiments not only clarify the differences between spores and sperm but also foster curiosity about the diversity of life’s reproductive strategies.

Master Spore Modding: A Step-by-Step Guide for Steam Users

You may want to see also

Structure Differences - Spores are single-celled and hardy; sperm are motile with a tail

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, exhibit stark structural differences that reflect their distinct functions and environments. Spores are single-celled entities designed for survival in harsh conditions. Their cell walls are thick and resilient, often composed of materials like chitin or sporopollenin, which provide protection against desiccation, radiation, and extreme temperatures. This hardiness allows spores to remain dormant for years, even centuries, until conditions are favorable for growth. In contrast, sperm cells are specialized for mobility and fertilization. Their structure is streamlined, featuring a compact head containing genetic material and a long, whip-like tail (flagellum) that propels them toward the egg. This motility is essential for their function but comes at the cost of fragility; sperm cannot survive outside their protective environment for long.

Consider the practical implications of these structural differences. For instance, in agriculture, fungal spores are used to inoculate crops because of their durability and ability to disperse over long distances. Gardeners often apply spore-based fungicides in low concentrations (e.g., 1–2 grams per liter of water) to ensure even coverage without waste. Sperm, on the other hand, are handled with extreme care in assisted reproductive technologies. During procedures like in vitro fertilization (IVF), sperm are typically washed and concentrated to a density of 5–20 million cells per milliliter to optimize fertilization rates. The fragility of sperm necessitates precise temperature control (around 37°C) and a pH-balanced medium to maintain viability.

From an evolutionary perspective, the structural differences between spores and sperm highlight contrasting reproductive strategies. Spores are a product of asexual reproduction, prioritizing survival and dispersal over immediate fertilization. Their single-celled nature and robust structure enable them to act as a genetic time capsule, waiting for the right moment to sprout. Sperm, however, are a hallmark of sexual reproduction, emphasizing speed and competition. Their motility allows them to navigate complex environments, such as the female reproductive tract, to reach the egg. This specialization, while effective, limits their lifespan and adaptability outside their intended habitat.

To illustrate these differences further, imagine a scenario where both spores and sperm are exposed to the same adverse conditions, such as dehydration or high salinity. Spores would likely persist, their protective layers shielding their genetic material from damage. Sperm, without their aqueous environment and energy reserves, would quickly lose viability. This comparison underscores the trade-off between durability and functionality. While spores excel in survival, sperm are optimized for a singular, time-sensitive task. Understanding these structural adaptations not only clarifies their roles in reproduction but also informs applications in fields like biotechnology, where harnessing the strengths of each can lead to innovations in preservation, propagation, and fertility treatments.

Breathing Mold Spores: Health Risks and Prevention Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Environmental Roles - Spores survive harsh conditions; sperm are short-lived and environment-sensitive

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, exhibit starkly different environmental tolerances. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are designed for survival. They can endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, often remaining dormant for years until conditions improve. For instance, bacterial endospores can survive boiling water for up to 20 minutes, a feat no sperm cell could achieve. This resilience allows spores to disperse widely, colonizing new habitats even in the harshest environments, from deserts to deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

In contrast, sperm cells are fragile and short-lived. Their primary function is rapid fertilization, not long-term survival. Human sperm, for example, can live inside the female reproductive tract for only 3–5 days, and their motility decreases significantly after 72 hours. Sperm require a stable, nutrient-rich environment with specific pH and temperature ranges—typically between 36.5°C and 37.5°C for mammals. Even slight deviations can impair their function. This sensitivity underscores their role as immediate agents of reproduction rather than long-term survivors.

The environmental sensitivity of sperm has practical implications for fields like agriculture and assisted reproduction. In livestock breeding, semen must be collected, diluted with extenders (e.g., Tris-based solutions), and stored at 4°C for no more than 24–48 hours before use. Cryopreservation, which involves cooling sperm to -196°C in liquid nitrogen, extends their viability but requires precise handling to avoid damage. Even then, only 40–60% of frozen-thawed sperm retain motility, highlighting their vulnerability.

Spores, on the other hand, are exploited in biotechnology for their durability. For example, *Bacillus thuringiensis* spores are used in bioinsecticides because they can withstand sunlight and rain, ensuring prolonged effectiveness in the field. Similarly, fungal spores like those of *Trichoderma* are applied in soil remediation due to their ability to survive harsh conditions while suppressing plant pathogens. These applications leverage spores’ environmental hardiness, a trait sperm lack entirely.

Understanding these differences is crucial for conservation and medical research. Efforts to preserve endangered species often focus on sperm banking, but the cells’ short lifespan necessitates frequent collection and optimal storage conditions. Conversely, spore-producing organisms can be conserved by simply storing their dormant forms, which can be revived decades later. This distinction highlights how evolutionary strategies shape reproductive units to fulfill specific ecological roles, with spores thriving in adversity and sperm thriving in immediacy.

Mastering Space Spore: Winning Strategies for Galactic Domination

You may want to see also

Organism Types - Spores in plants/fungi; sperm in animals, highlighting distinct biological kingdoms

Spores and sperm are both reproductive units, yet they serve distinct purposes across different biological kingdoms. In plants and fungi, spores are the primary means of asexual reproduction, allowing these organisms to disperse and colonize new environments efficiently. For instance, ferns release lightweight spores that can travel vast distances on air currents, ensuring survival in diverse habitats. Fungi, such as mushrooms, produce spores in the trillions, enabling rapid proliferation even in nutrient-poor conditions. These spores are hardy, capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, drought, and other environmental stresses, making them a highly effective survival mechanism.

In contrast, sperm in animals is a specialized reproductive cell designed for sexual reproduction, requiring the fusion with an egg to form a new organism. Unlike spores, sperm are motile, equipped with a flagellum to swim toward the egg, a feature absent in the passive dispersal of spores. For example, human sperm cells are microscopic, measuring about 50 micrometers in length, and can survive in the female reproductive tract for up to five days. Their primary function is to deliver genetic material, not to survive independently in harsh environments. This highlights a fundamental difference: spores are self-sustaining units of life, while sperm are transient carriers of genetic information.

The distinction between spores and sperm also reflects the evolutionary strategies of their respective kingdoms. Plants and fungi often thrive in unpredictable environments, where asexual reproduction via spores ensures genetic consistency and rapid colonization. Animals, however, rely on sexual reproduction to introduce genetic diversity, a critical factor in adapting to changing environments. For instance, a single fungal spore can grow into a new organism identical to its parent, whereas sperm must combine with an egg to create offspring with unique genetic traits. This divergence underscores the adaptability of life across kingdoms.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in agriculture and medicine. Farmers use spore-based fungicides to control plant diseases, leveraging the resilience of spores to combat pathogens. In contrast, assisted reproductive technologies in humans, such as in vitro fertilization, rely on the viability and motility of sperm. Understanding these differences allows scientists to manipulate reproductive processes for specific outcomes, whether it’s enhancing crop yields or addressing infertility. For example, storing fungal spores in desiccated conditions can preserve them for years, while sperm must be cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen at -196°C to maintain viability.

In summary, while spores and sperm share the common goal of reproduction, their structures, functions, and ecological roles are vastly different. Spores in plants and fungi are robust, asexual units designed for survival and dispersal, whereas sperm in animals are specialized cells optimized for sexual reproduction. Recognizing these distinctions not only deepens our understanding of biological diversity but also informs practical applications in fields ranging from ecology to medicine. This comparison underscores the ingenuity of life’s strategies across distinct biological kingdoms.

Mastering Spores in Baldur's Gate 3: Effective Strategies to Overcome Challenges

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a spore is not the same as sperm. Spores are reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms, while sperm is a male reproductive cell in animals.

Spores and sperm serve different reproductive purposes. Spores are used for asexual or sexual reproduction in organisms like fungi and plants, whereas sperm is involved in sexual reproduction in animals by fertilizing eggs.

No, spores cannot fertilize eggs. Spores are designed for dispersal and growth into new organisms, while sperm specifically fertilizes eggs in animals to create offspring.

Spores can be involved in both asexual and sexual reproduction, depending on the organism. Sperm, however, is exclusively involved in sexual reproduction in animals, combining with an egg to form a zygote.