The zygospore is a unique structure in the fungal kingdom, often sparking curiosity about its role in fungal reproduction. As a specialized cell, it forms through the fusion of two compatible haploid hyphae, marking a significant event in the sexual reproduction of certain fungi, particularly within the Zygomycota phylum. This process, known as zygosporation, results in the creation of a thick-walled, highly resistant zygospore, which can remain dormant for extended periods, ensuring the fungus's survival in harsh conditions. The question of whether a zygospore is indeed a sexual fungal spore is central to understanding fungal life cycles, as it highlights the distinction between asexual and sexual reproductive strategies in fungi, with zygospores being a clear indicator of sexual reproduction.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Spore | Sexual fungal spore |

| Formation | Results from the fusion of two compatible haploid hyphae or gametangia |

| Parent Structures | Formed within a zygosporangium after plasmogamy and karyogamy |

| Ploidy | Diploid (2n) |

| Function | Serves as a dormant, resistant stage in the fungal life cycle |

| Germination | Can germinate to produce a sporangium or directly form new hyphae under favorable conditions |

| Examples | Found in Zygomycota (e.g., Rhizopus, Mucor) |

| Significance | Represents a key stage in sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to environmental stresses such as desiccation and temperature extremes |

| Shape and Size | Thick-walled, often spherical or oval, and larger than asexual spores |

| Genetic Recombination | Facilitates genetic recombination through the fusion of haploid nuclei |

What You'll Learn

Zygospore formation process in fungi

Zygospores are indeed sexual fungal spores, formed through a specialized reproductive process that ensures genetic diversity and survival under adverse conditions. This process, known as zygospore formation, is a hallmark of the Zygomycota phylum, though similar mechanisms exist in other fungal groups. Unlike asexual spores, which are clones of the parent organism, zygospores result from the fusion of gametangia—hyphal structures containing haploid nuclei—from two compatible mating types. This sexual fusion creates a diploid zygote, which then develops into a thick-walled, dormant zygospore capable of withstanding harsh environments.

The zygospore formation process begins with the recognition of compatible mating types, often triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient scarcity or desiccation. Once compatible hyphae detect each other, they grow toward one another, forming specialized structures called gametangia. In Zygomycota, these are typically suspensor and zygosporangium, which align and fuse at their tips. The cytoplasm and nuclei from both gametangia mix, leading to the formation of a diploid zygote within a zygosporangium. This zygote then undergoes karyogamy, where the nuclei fuse, followed by meiosis to restore haploidy before the zygospore germinates.

One of the most fascinating aspects of zygospore formation is its adaptability. For example, in *Rhizopus stolonifer*, a common bread mold, zygospores can remain dormant for years, only germinating when conditions improve. This resilience is due to the zygospore’s thick, melanized cell wall, which protects against UV radiation, heat, and desiccation. Practical applications of this knowledge include controlling fungal growth in food storage—reducing moisture and nutrients can prevent zygospore germination—and harnessing zygospores in biotechnology for their ability to produce enzymes under stress.

Comparatively, zygospore formation differs from other sexual fungal spores, such as asci in Ascomycota or basidia in Basidiomycota, in its simplicity and directness. While those groups produce multiple spores per sexual structure, Zygomycota typically produces a single zygospore per fusion event. This efficiency reflects the zygospore’s role as a survival mechanism rather than a means of rapid dispersal. For instance, in agricultural settings, understanding this process can help manage soil fungi by manipulating environmental conditions to inhibit zygospore formation.

In conclusion, zygospore formation is a critical sexual reproductive strategy in fungi, combining genetic recombination with environmental resilience. By studying this process, researchers can develop targeted interventions for fungal control and leverage zygospores’ unique properties in biotechnology. Whether in a laboratory or a field, understanding zygospore formation offers practical insights into managing fungal populations and harnessing their potential.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Using Spore Prints for Successful Growth

You may want to see also

Differences between zygospores and asexual spores

Zygospores and asexual spores are fundamentally different in their origin, structure, and function, reflecting their distinct roles in fungal reproduction. Zygospores are formed through the fusion of two compatible haploid gametangia, a process that involves the merging of genetic material from two individuals. This sexual reproduction mechanism ensures genetic diversity, a critical factor for fungi to adapt to changing environments. In contrast, asexual spores, such as conidia or sporangiospores, are produced by a single parent without the fusion of gametes. This method allows for rapid proliferation but limits genetic variation, as the offspring are genetically identical or nearly identical to the parent.

Structurally, zygospores are typically thick-walled and highly resilient, designed to withstand harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. This durability enables them to remain dormant for extended periods until environmental conditions become favorable for germination. Asexual spores, on the other hand, often have thinner walls and are more susceptible to environmental stressors. For example, conidia, a common type of asexual spore, are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, facilitating quick colonization of new habitats but at the cost of reduced longevity.

The functional differences between these spore types are equally pronounced. Zygospores serve as a long-term survival mechanism, ensuring the persistence of fungal species across generations. They are less about rapid spread and more about endurance. Asexual spores, however, are optimized for immediate dispersal and colonization. For instance, a single fungal colony can produce thousands of conidia within hours, allowing it to quickly exploit available resources. This distinction highlights the trade-off between survival and proliferation in fungal reproductive strategies.

Practical considerations for identifying these spores in a laboratory or field setting are essential. Zygospores are often larger and more distinctive in shape, such as the spherical zygospores of *Zygomycota*. They can be observed under a microscope following staining techniques like lactophenol cotton blue, which enhances their thick walls. Asexual spores, particularly conidia, are smaller and may require higher magnification or specific culturing techniques to visualize. For example, tape preparations or slide cultures can be used to collect and examine conidia from fungal colonies.

In summary, while both zygospores and asexual spores are vital to fungal life cycles, their differences in origin, structure, and function underscore their unique ecological roles. Understanding these distinctions not only aids in taxonomic identification but also provides insights into fungal survival strategies. Whether in research, agriculture, or environmental management, recognizing these spores can inform strategies to control fungal growth or harness their benefits effectively.

Mastering Planetary Descent: A Guide to Beaming Down in Spore

You may want to see also

Role of zygospores in fungal reproduction

Zygospores are indeed sexual fungal spores, formed through the fusion of gametangia from compatible mating types in certain fungi, primarily within the phylum Zygomycota. This process, known as zygosporangium formation, is a critical mechanism for genetic recombination and long-term survival in harsh environments. Unlike asexual spores, which are clones of the parent organism, zygospores result from the union of haploid nuclei, creating a diploid zygote that can remain dormant for extended periods. This sexual reproduction strategy ensures genetic diversity, a key factor in fungal adaptation and evolution.

Consider the life cycle of *Rhizopus stolonifer*, a common bread mold. When nutrients become scarce or environmental conditions deteriorate, hyphae from compatible mating types produce gametangia that fuse to form a thick-walled zygospore. This structure is remarkably resilient, capable of withstanding desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other stressors. Once conditions improve, the zygospore germinates, undergoes meiosis, and produces sporangiospores that can colonize new substrates. This cycle highlights the zygospore’s dual role: as a means of genetic exchange and as a survival mechanism.

From a practical standpoint, understanding zygospores is essential for managing fungal pathogens and optimizing biotechnological applications. For instance, in agriculture, zygospore formation in soil fungi can lead to sudden outbreaks of disease when conditions become favorable. Farmers can mitigate this by rotating crops and maintaining soil health to disrupt fungal life cycles. Conversely, in biotechnology, zygospores are exploited for their ability to produce secondary metabolites, such as antibiotics and enzymes, under stress conditions. Researchers induce zygospore formation in controlled environments to harvest these valuable compounds.

Comparatively, zygospores differ from other sexual fungal spores, like asci and basidia, in their structure and function. While asci and basidia release multiple haploid spores after karyogamy and meiosis, zygospores remain as a single, thick-walled cell until germination. This distinction reflects the diverse reproductive strategies fungi employ to thrive in varied ecosystems. For example, zygospores are more common in saprotrophic fungi, which decompose organic matter, whereas asci and basidia are prevalent in symbiotic and pathogenic species.

In conclusion, zygospores play a pivotal role in fungal reproduction by facilitating genetic diversity and ensuring survival in adverse conditions. Their formation is a testament to the adaptability of fungi, enabling them to colonize diverse habitats and respond to environmental challenges. Whether in the lab, field, or industry, recognizing the significance of zygospores provides valuable insights into fungal biology and its practical implications. By studying these structures, we can better manage fungal interactions and harness their potential for human benefit.

Crafting a Shroom Spore Syringe: Step-by-Step DIY Guide

You may want to see also

Conditions triggering zygospore development

Zygospores are indeed sexual fungal spores, formed through the fusion of gametangia from compatible mating types in certain fungi, primarily within the phylum Zygomycota. This process, known as zygosporogenesis, is a critical reproductive strategy for these organisms. However, zygospore development is not a spontaneous event; it is triggered by specific environmental and physiological conditions that signal the need for long-term survival or genetic recombination. Understanding these triggers is essential for both mycologists and those applying fungal biology in agriculture or biotechnology.

Environmental Cues: The Role of Stress and Nutrient Depletion

Zygospore formation is often induced by adverse environmental conditions, such as nutrient scarcity, desiccation, or extreme temperatures. For example, in *Mucor* and *Rhizopus* species, starvation triggers the differentiation of gametangia, which then fuse to form zygospores. This response is adaptive, as zygospores are highly resilient structures capable of surviving harsh conditions for years. Laboratory studies show that reducing nitrogen or carbon sources in growth media accelerates zygospore development, mimicking natural nutrient depletion. Practically, maintaining a controlled nutrient-poor environment can induce zygospore formation in fungal cultures, a technique useful in research and industrial settings.

Physiological Triggers: Mating Compatibility and Hormonal Signals

Beyond external stressors, internal physiological factors play a pivotal role. Zygospore development requires the interaction of compatible mating types, often determined by alleles at a single mating-type locus. In *Zygomycota*, pheromone signaling between compatible individuals initiates the process. For instance, in *Phycomyces blakesleeanus*, mating pheromones induce gametangial swelling and fusion. Researchers have identified specific pheromone concentrations (e.g., 10^-8 M) as optimal for triggering this response. Ensuring mating compatibility and providing pheromone cues are critical steps for inducing zygospore formation in experimental setups.

Comparative Analysis: Zygospores vs. Other Fungal Spores

Unlike asexual spores (e.g., conidia or spores), zygospores are not produced under favorable conditions. Their development is a last resort, triggered by environmental extremes or genetic necessity. This contrasts with asexual sporulation, which occurs during vegetative growth. For example, while *Aspergillus* species readily produce conidia in nutrient-rich conditions, zygospores in *Rhizopus* require nutrient deprivation. This distinction highlights the unique ecological role of zygospores as survival structures rather than dispersal agents.

Practical Applications: Manipulating Conditions for Zygospore Induction

For researchers and biotechnologists, understanding these triggers allows for controlled zygospore production. A step-by-step approach includes: (1) identifying compatible mating types, (2) inducing stress by reducing nutrients (e.g., cutting carbon sources by 70%), and (3) maintaining optimal pheromone concentrations. Caution must be taken to avoid over-stressing cultures, as prolonged starvation can lead to cell death. This method is particularly useful in studying zygospore genetics or producing resilient fungal strains for agricultural applications.

In summary, zygospore development is a finely tuned response to environmental and physiological cues, ensuring fungal survival under adverse conditions. By manipulating these triggers, scientists can harness the unique properties of zygospores for research and practical applications, underscoring their significance in fungal biology.

Exploring the Surprising Diversity Among Commonly Assumed Similar Spores

You may want to see also

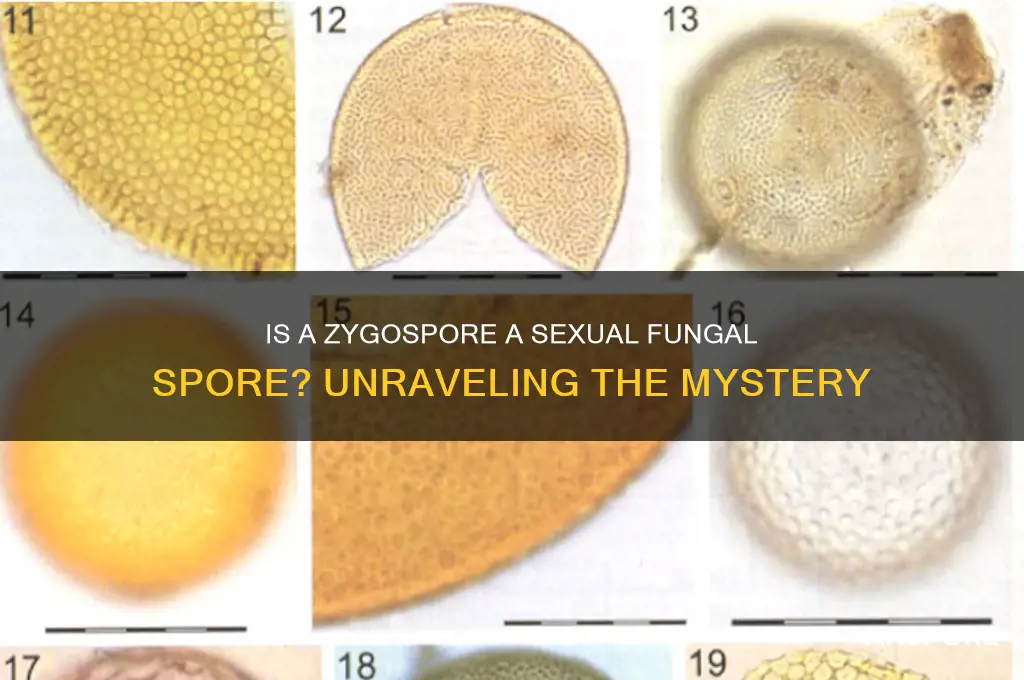

Zygospore structure and genetic composition

Zygospores, formed through the fusion of gametangia in certain fungi, represent a remarkable example of sexual reproduction in the microbial world. Structurally, a zygospore is a thick-walled, highly resilient spore that serves as a survival mechanism in adverse environmental conditions. Its wall, composed of multiple layers including chitin and other complex polymers, provides protection against desiccation, extreme temperatures, and predation. This robust structure allows zygospores to remain dormant for extended periods, sometimes even decades, until conditions become favorable for germination.

Genetically, zygospores are diploid, resulting from the fusion of two haploid nuclei during karyogamy. This genetic recombination introduces diversity, a critical advantage in evolving fungal populations. The diploid nucleus within the zygospore undergoes meiosis upon germination, producing haploid spores that can disperse and colonize new environments. This process not only ensures genetic variability but also enhances the species' adaptability to changing ecosystems. For instance, in *Zygorhynchus* species, the zygospore's genetic composition has been studied to understand how fungi respond to environmental stressors like nutrient scarcity or climate fluctuations.

To illustrate the practical significance of zygospore structure and genetics, consider their role in agriculture. Farmers and mycologists can exploit the zygospore's durability to preserve beneficial fungal strains for biocontrol agents. By isolating zygospores from fungi like *Glomus* (arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi), which enhance plant nutrient uptake, these spores can be stored and later reintroduced to soil to improve crop yields. However, caution must be exercised to prevent contamination during storage, as zygospores' resilience can also protect unwanted pathogens.

A comparative analysis of zygospores across different fungal phyla reveals variations in wall thickness and genetic expression. For example, zygospores in the phylum Zygomycota exhibit thicker walls compared to those in Chytridiomycota, reflecting adaptations to their respective habitats. Such differences underscore the importance of tailoring preservation and cultivation techniques to specific fungal species. Researchers can use this knowledge to optimize laboratory conditions for studying zygospore germination, ensuring accurate replication of natural processes.

In conclusion, understanding zygospore structure and genetic composition is essential for both scientific inquiry and practical applications. From their role in genetic diversity to their utility in agriculture, zygospores exemplify the intricate interplay between form and function in fungal biology. By studying these spores, we gain insights into fungal survival strategies and unlock potential solutions for challenges in agriculture, ecology, and biotechnology.

Fern Growth Timeline: From Spore to Plant – What to Expect

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, a zygospore is a sexual fungal spore formed through the fusion of two compatible haploid gametangia in certain fungi, such as Zygomycota.

A zygospore is formed through sexual reproduction, involving the fusion of gametes, while asexual fungal spores (like conidia or spores) are produced without fertilization and do not involve genetic recombination.

The primary function of a zygospore is to serve as a thick-walled, dormant structure that allows the fungus to survive harsh environmental conditions until favorable conditions return for germination.

Zygospores are primarily produced by fungi in the phylum Zygomycota, though similar structures may occur in some other fungal groups under specific conditions.