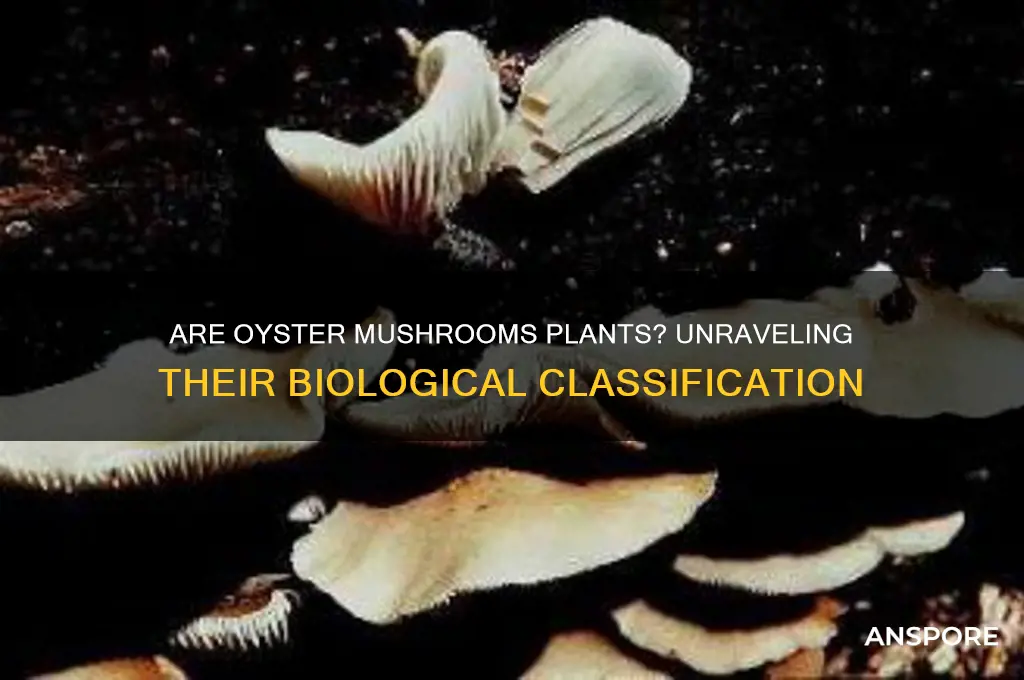

The question of whether an oyster mushroom is a plant is a common one, but it stems from a misunderstanding of the biological classification of fungi. Unlike plants, which produce their own food through photosynthesis, oyster mushrooms belong to the kingdom Fungi and are heterotrophs, obtaining nutrients by breaking down organic matter. They lack chlorophyll, roots, and other plant-like structures, instead growing from mycelium and producing fruiting bodies. This fundamental difference in biology and nutrition distinguishes oyster mushrooms from plants, placing them in a separate and unique category of life.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division | Basidiomycota |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Pleurotaceae |

| Genus | Pleurotus |

| Species | Pleurotus ostreatus (common oyster mushroom) |

| Cellular Structure | Eukaryotic, with chitinous cell walls |

| Nutrition | Absorbs nutrients from decaying organic matter (saprotrophic) |

| Photosynthesis | No, does not contain chlorophyll |

| Reproduction | Asexual (via spores) and sexual (via mycelium fusion) |

| Growth Medium | Typically grows on dead or decaying wood |

| Classification | Not a plant; belongs to the fungi kingdom |

| Ecological Role | Decomposer, breaks down lignin and cellulose in wood |

| Edibility | Edible and widely cultivated for food |

| Habitat | Temperate and subtropical forests |

| Lifespan | Short-lived fruiting bodies, but mycelium can persist longer |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Oyster Mushroom Classification: Are they fungi or plants Understanding their biological kingdom

- Plant vs. Fungus Traits: Comparing cellular structure, nutrition methods, and growth patterns

- Photosynthesis Absence: Why oyster mushrooms don’t produce energy like plants

- Mycelium Networks: How fungi differ from plant root systems in nutrient absorption

- Reproduction Methods: Spores vs. seeds: key differences in how they multiply

Oyster Mushroom Classification: Are they fungi or plants? Understanding their biological kingdom

Oyster mushrooms, scientifically known as *Pleurotus ostreatus*, are often mistaken for plants due to their appearance and growth habits. However, they do not belong to the plant kingdom. Instead, oyster mushrooms are classified as fungi, a distinct biological kingdom separate from plants, animals, and bacteria. This classification is based on fundamental differences in their cellular structure, mode of nutrition, and reproductive processes. Unlike plants, which produce their own food through photosynthesis, fungi like oyster mushrooms are heterotrophs, obtaining nutrients by breaking down organic matter in their environment.

The confusion between fungi and plants arises partly because both are stationary and grow in similar environments, such as soil or decaying wood. However, the biological distinctions are clear. Plants have cells with rigid cell walls made of cellulose, chloroplasts for photosynthesis, and a vascular system for transporting water and nutrients. In contrast, fungi, including oyster mushrooms, have cell walls composed of chitin, lack chloroplasts, and do not possess a true vascular system. Instead, fungi absorb nutrients directly through their cell walls via a network of thread-like structures called hyphae.

Oyster mushrooms, as fungi, play a unique ecological role as decomposers. They break down complex organic materials like lignin and cellulose in dead wood, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. This process is essential for nutrient cycling and soil health, highlighting the importance of fungi in maintaining ecological balance. Their classification as fungi also explains their inability to produce seeds or flowers, traits commonly associated with plants. Instead, fungi reproduce through spores, which are dispersed into the environment to colonize new substrates.

Understanding the biological kingdom of oyster mushrooms is crucial for their cultivation and use. As fungi, they require specific conditions, such as a substrate rich in organic matter and controlled humidity, to thrive. This knowledge informs agricultural practices, allowing growers to optimize conditions for mushroom production. Additionally, recognizing oyster mushrooms as fungi clarifies their nutritional profile, which differs significantly from plants. They are low in calories, rich in protein, and contain bioactive compounds with potential health benefits, making them a valuable addition to diets.

In summary, oyster mushrooms are definitively fungi, not plants, based on their biological characteristics and ecological functions. Their classification in the fungal kingdom is supported by their chitinous cell walls, heterotrophic nutrition, and spore-based reproduction. While they may resemble plants in some ways, their distinct biology sets them apart. This understanding not only resolves common misconceptions but also underscores the unique role of fungi in ecosystems and their practical applications in agriculture and nutrition.

Mushrooms' Intriguing Sexual Reproduction

You may want to see also

Plant vs. Fungus Traits: Comparing cellular structure, nutrition methods, and growth patterns

Oyster mushrooms, like all fungi, are fundamentally different from plants in several key biological aspects. To understand why an oyster mushroom is not a plant, it’s essential to compare their cellular structure, nutrition methods, and growth patterns. These distinctions highlight the unique characteristics of fungi and plants, placing oyster mushrooms firmly in the fungal kingdom.

Cellular Structure: Plant vs. Fungus

Plants and fungi differ significantly in their cellular composition. Plant cells are eukaryotic and contain rigid cell walls made of cellulose, chloroplasts for photosynthesis, and a large central vacuole. In contrast, fungal cells, including those of oyster mushrooms, have cell walls composed of chitin, a substance not found in plants. Fungi lack chloroplasts and thus cannot perform photosynthesis. Additionally, fungal cells often form a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which collectively make up the mycelium. This mycelial network is a defining feature of fungi and is absent in plants. Oyster mushrooms, therefore, exhibit classic fungal cellular traits, not plant traits.

Nutrition Methods: Autotrophy vs. Heterotrophy

One of the most critical distinctions between plants and fungi is their method of obtaining nutrients. Plants are autotrophs, meaning they produce their own food through photosynthesis, converting sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into glucose. Fungi, including oyster mushrooms, are heterotrophs. They obtain nutrients by breaking down organic matter externally through enzymes secreted by their hyphae. Oyster mushrooms decompose dead wood, leaves, and other organic substrates, absorbing the released nutrients directly into their mycelium. This saprotrophic lifestyle contrasts sharply with the photosynthetic nutrition of plants.

Growth Patterns: Structured vs. Networked Growth

The growth patterns of plants and fungi also differ markedly. Plants grow in a structured, directional manner, with roots anchoring them in the soil and shoots reaching toward light. Their growth is determined by apical meristems, which produce new cells for roots and shoots. Fungi, however, grow through the extension of their hyphal network, which can spread in all directions in search of nutrients. Oyster mushrooms develop fruiting bodies (the visible mushrooms) only under specific conditions, and these structures emerge from the underlying mycelium. This networked, exploratory growth is a hallmark of fungi and contrasts with the localized, structured growth of plants.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: Spores vs. Seeds

Reproduction further distinguishes plants from fungi. Plants reproduce via seeds, which contain an embryo and stored nutrients, and often rely on external agents like wind, water, or animals for dispersal. Fungi, including oyster mushrooms, reproduce through spores, which are microscopic, lightweight, and produced in vast quantities. These spores are dispersed through air currents and germinate when they land in a suitable environment. The life cycle of fungi is dominated by the vegetative mycelium phase, with the fruiting body (mushroom) serving primarily for spore production. This spore-based reproduction and the prominence of the mycelium phase are distinctly fungal traits.

In conclusion, while oyster mushrooms may superficially resemble plants due to their visible fruiting bodies, they are unequivocally fungi. Their chitinous cell walls, heterotrophic nutrition, networked growth patterns, and spore-based reproduction align them with the fungal kingdom, not the plant kingdom. Understanding these traits clarifies why an oyster mushroom is not a plant but a fascinating example of fungal biology.

Unlocking the Secrets to Cooking Mushrooms in an Instant Pot

You may want to see also

Photosynthesis Absence: Why oyster mushrooms don’t produce energy like plants

Oyster mushrooms, like all fungi, are fundamentally different from plants in how they obtain and utilize energy. One of the most striking differences is the absence of photosynthesis in fungi. Plants, algae, and some bacteria perform photosynthesis, a process that converts sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water into glucose (a form of energy) and oxygen. This process relies on chlorophyll, a green pigment found in plant cells. Oyster mushrooms, however, lack chlorophyll and the cellular structures (chloroplasts) necessary for photosynthesis. As a result, they cannot produce their own energy from sunlight, which immediately sets them apart from plants in terms of energy acquisition.

Instead of photosynthesis, oyster mushrooms are heterotrophs, meaning they obtain energy by breaking down organic matter. Fungi secrete enzymes into their environment to decompose complex organic materials, such as dead wood, leaves, or other plant debris. These enzymes break down substances like cellulose and lignin into simpler compounds, which the mushroom then absorbs and metabolizes for energy. This process, known as extracellular digestion, is a hallmark of fungal biology and contrasts sharply with the autotrophic nature of plants. While plants create their own food, oyster mushrooms rely entirely on external sources, highlighting their distinct ecological role as decomposers rather than producers.

The absence of photosynthesis in oyster mushrooms also reflects their evolutionary history and cellular structure. Fungi belong to a separate kingdom from plants, with unique cell walls composed of chitin rather than cellulose. Their evolutionary path diverged from plants over a billion years ago, leading to distinct adaptations for survival. Unlike plants, which evolved to harness sunlight, fungi adapted to thrive in dark, nutrient-rich environments, such as forest floors or decaying matter. This evolutionary divergence explains why oyster mushrooms lack the genetic and biochemical machinery for photosynthesis and instead excel at breaking down organic material.

Another critical aspect of photosynthesis absence in oyster mushrooms is their dependency on environmental conditions. Plants can grow in sunlight-rich areas, using photosynthesis to fuel their growth. In contrast, oyster mushrooms require shaded, moist environments where organic matter is abundant. Their growth is closely tied to the availability of substrates they can decompose, such as straw or wood chips. This dependency underscores their role as saprotrophs, organisms that obtain nutrients from non-living organic matter, rather than as primary producers like plants.

Understanding the absence of photosynthesis in oyster mushrooms also clarifies why they are not classified as plants. While both fungi and plants are eukaryotic organisms, their methods of energy acquisition, cellular structure, and ecological roles are vastly different. Oyster mushrooms’ inability to photosynthesize is a defining characteristic that places them firmly in the fungal kingdom. This distinction is essential for fields like biology, agriculture, and ecology, where accurate classification and understanding of organisms’ roles in ecosystems are crucial. In summary, the absence of photosynthesis in oyster mushrooms is not just a biological detail but a fundamental aspect that shapes their identity, function, and relationship to the natural world.

Leeks and Mushrooms: A Flavorful Pairing or Culinary Clash?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.99 $19.99

Mycelium Networks: How fungi differ from plant root systems in nutrient absorption

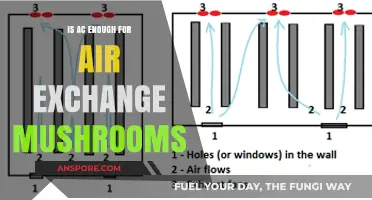

Fungi, including oyster mushrooms, are fundamentally different from plants in their biological classification and nutrient absorption mechanisms. While plants are part of the kingdom Plantae and rely on photosynthesis to produce energy, fungi belong to the kingdom Fungi and are heterotrophs, obtaining nutrients by breaking down organic matter. This distinction is crucial when comparing how fungi and plants absorb nutrients. Fungi achieve this through their mycelium networks, a vast web of thread-like structures called hyphae, which operate differently from plant root systems.

Mycelium networks excel in nutrient absorption due to their expansive and intricate structure. Unlike plant roots, which grow deeper into the soil primarily for water and mineral uptake, mycelium spreads horizontally and vertically, covering a much larger area. This extensive network allows fungi to access nutrients from a broader range of sources, including dead organic material, which plants cannot utilize directly. The hyphae secrete enzymes that break down complex organic compounds into simpler forms, such as sugars and amino acids, which the fungus then absorbs. This process, known as extracellular digestion, is unique to fungi and contrasts with plant roots, which primarily absorb already dissolved nutrients from the soil.

Another key difference lies in the symbiotic relationships fungi form with other organisms. Mycelium networks often engage in mutualistic associations, such as mycorrhizae, where fungi partner with plant roots to enhance nutrient exchange. In these relationships, the fungus provides plants with hard-to-access nutrients like phosphorus, while the plant supplies the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. While plant roots can also form symbiotic relationships, the extent and complexity of fungal mycelium networks in facilitating nutrient transfer are unparalleled. This symbiotic capability highlights the unique role of fungi in ecosystem nutrient cycling.

The efficiency of mycelium networks in nutrient absorption is further demonstrated by their ability to thrive in nutrient-poor environments. Fungi can extract nutrients from substrates that are inaccessible to plants, such as wood, straw, and even rocks. This adaptability is due to the hyphae's thin diameter and high surface-to-volume ratio, which maximizes contact with the surrounding environment. In contrast, plant roots are more limited in their ability to penetrate and extract nutrients from such materials. Additionally, mycelium networks can store nutrients internally, creating a reservoir that can be redistributed as needed, a feature not observed in plant root systems.

In summary, mycelium networks differ from plant root systems in their structure, nutrient acquisition strategies, and ecological roles. Fungi rely on extracellular digestion, expansive hyphal networks, and symbiotic relationships to absorb nutrients, whereas plants primarily absorb dissolved nutrients through their roots. Understanding these differences is essential for recognizing the unique contributions of fungi, like oyster mushrooms, to ecosystems and their distinction from plants. This knowledge also underscores the importance of fungi in processes such as decomposition and nutrient cycling, which are vital for soil health and ecosystem functioning.

Mushroom Tea: Caffeine or Not?

You may want to see also

Reproduction Methods: Spores vs. seeds: key differences in how they multiply

Oyster mushrooms, like all fungi, are not plants. They belong to a separate kingdom of organisms called Fungi, which sets them apart from plants in terms of structure, nutrition, and reproduction. One of the most significant differences lies in their reproductive methods. While plants primarily reproduce using seeds, fungi, including oyster mushrooms, rely on spores. Understanding the distinctions between spores and seeds is crucial to grasping how these organisms multiply and thrive in their respective environments.

Spores: The Fungal Reproductive Units

Spores are microscopic, single-celled structures produced by fungi for reproduction. In oyster mushrooms, spores are generated in the gills located on the underside of the cap. When mature, these spores are released into the environment, often carried by air currents. Unlike seeds, spores do not contain an embryo or stored nutrients. Instead, they are lightweight and can travel vast distances, allowing fungi to colonize new habitats efficiently. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment with adequate moisture and organic matter, it germinates and grows into a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which eventually form the mushroom’s fruiting body. This asexual method of reproduction enables rapid proliferation under favorable conditions.

Seeds: The Plant Reproductive Strategy

Seeds, in contrast, are the primary reproductive units of plants. They are multicellular structures that contain an embryo, stored food (such as endosperm or cotyledons), and a protective outer layer. Seeds are typically produced after fertilization, a process involving the fusion of male and female gametes. Unlike spores, seeds are heavier and often rely on external agents like wind, water, or animals for dispersal. Once a seed lands in a suitable environment, it germinates, using the stored nutrients to grow into a new plant. This method ensures that the offspring has the resources needed to establish itself, even in less-than-ideal conditions.

Key Differences in Multiplication

The primary difference between spores and seeds lies in their structure, function, and dispersal mechanisms. Spores are simple, single-celled units designed for widespread dispersal and rapid colonization, whereas seeds are complex, nutrient-rich structures that support the early growth of a new plant. Additionally, spores are produced asexually, allowing for quick multiplication without the need for a mate, while seeds result from sexual reproduction, promoting genetic diversity. These differences reflect the distinct ecological roles of fungi and plants: fungi are decomposers that thrive on organic matter, while plants are producers that rely on photosynthesis.

Implications for Oyster Mushrooms

For oyster mushrooms, spore-based reproduction is highly effective in their role as decomposers. Their ability to produce vast quantities of spores ensures that they can quickly colonize dead wood or other organic substrates, breaking them down and recycling nutrients in ecosystems. This method contrasts sharply with seed-based reproduction in plants, which is more energy-intensive but provides offspring with a head start in growth. By relying on spores, oyster mushrooms exemplify the efficiency and adaptability of fungal reproductive strategies, further highlighting why they are not classified as plants.

Whole Foods Mushroom Stock: What's Available?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, an oyster mushroom is not a plant. It is a type of fungus, belonging to the kingdom Fungi, which is distinct from the kingdom Plantae.

Oyster mushrooms are often confused with plants because they grow in soil or on organic matter, similar to some plants. However, they lack chlorophyll and do not perform photosynthesis, which are key characteristics of plants.

The main differences are that oyster mushrooms are fungi, lack chlorophyll, do not have roots, stems, or leaves, and obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter, whereas plants are part of the kingdom Plantae, contain chlorophyll, and produce their own food through photosynthesis.