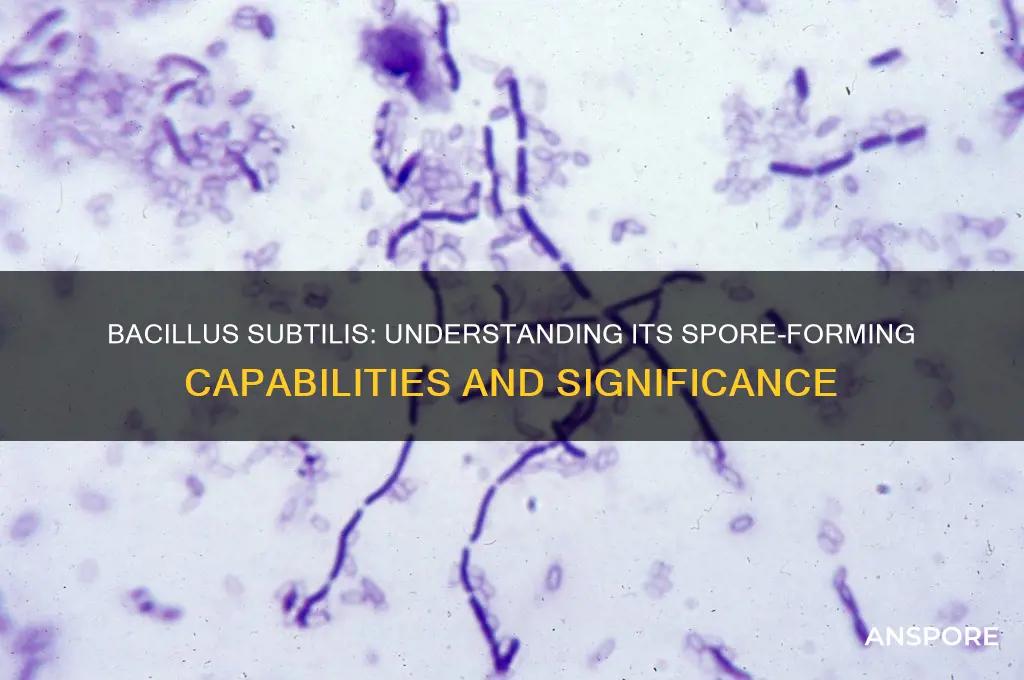

Bacillus subtilis is a well-studied, Gram-positive bacterium known for its remarkable ability to form endospores, which are highly resistant structures that allow the organism to survive extreme environmental conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. This spore-forming capability is a defining characteristic of the species and plays a crucial role in its ecological success and industrial applications. When exposed to nutrient depletion or other stressors, B. subtilis undergoes a complex process of sporulation, resulting in the formation of a dormant spore that can remain viable for extended periods until favorable conditions return. Understanding the mechanisms and significance of spore formation in B. subtilis not only sheds light on its survival strategies but also informs its use in biotechnology, agriculture, and food production.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | Yes, Bacillus subtilis is a well-known spore-forming bacterium. |

| Spore Type | Endospore (formed within the vegetative cell). |

| Spore Location | Central or terminal in the cell. |

| Spore Shape | Oval or round. |

| Spore Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. |

| Spore Germination | Can germinate under favorable conditions (e.g., nutrients, moisture). |

| Spore Function | Survival mechanism during harsh environmental conditions. |

| Spore Formation Conditions | Triggered by nutrient depletion or other stress factors. |

| Spore Composition | Composed of dipicolinic acid, calcium, and a thick spore coat. |

| Spore Lifespan | Can remain viable for years or even decades. |

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: How does B. subtilis initiate and complete endospore formation under stress

- Spore Structure: Key components and layers of B. subtilis spores for survival

- Spore Germination: Conditions and triggers for B. subtilis spore revival

- Survival Advantages: Benefits of spore formation in B. subtilis for longevity

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like nutrient depletion inducing spore formation in B. subtilis

Spore Formation Process: How does B. subtilis initiate and complete endospore formation under stress?

Bacillus subtilis, a Gram-positive bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form endospores under stress conditions. This process, known as sporulation, is a survival mechanism that allows the bacterium to withstand extreme environments such as nutrient depletion, desiccation, and high temperatures. Understanding how B. subtilis initiates and completes endospore formation is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications in biotechnology and medicine.

The sporulation process in B. subtilis is tightly regulated and involves a series of well-coordinated steps. It begins with the activation of specific genes in response to stress signals, primarily nutrient limitation. When starved, the bacterium senses the lack of essential nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus through signaling pathways such as the phosphorelay system. This triggers the activation of the master regulator Spo0A, which initiates the sporulation cascade. Spo0A phosphorylates and activates genes involved in the early stages of sporulation, setting the stage for the formation of the endospore.

As sporulation progresses, the bacterial cell undergoes asymmetric division, creating a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. This division is mediated by proteins like FtsZ, which localize to the septation site. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, forming a double-membrane structure. Within this structure, the forespore develops a thick, protective coat composed of proteins and peptidoglycan. Concurrently, the mother cell synthesizes and secretes enzymes that degrade its own DNA and cellular components, providing nutrients for the developing endospore. This altruistic behavior ensures the survival of the forespore, which eventually matures into a highly resistant endospore.

The completion of endospore formation involves the deposition of additional layers, including the cortex (rich in peptidoglycan) and the outer spore coat. These layers provide mechanical strength and chemical resistance, enabling the endospore to survive harsh conditions for extended periods. Notably, B. subtilis endospores can remain dormant for years, only to germinate and resume vegetative growth when favorable conditions return. This resilience makes B. subtilis a model organism for studying stress responses and a valuable tool in industrial applications, such as probiotic production and enzyme stabilization.

Practical tips for inducing sporulation in B. subtilis include culturing the bacterium in nutrient-limited media, such as Difco Sporulation Medium, and maintaining conditions that mimic starvation. Researchers often monitor sporulation efficiency by staining cells with dyes like malachite green or by assessing heat resistance, as mature endospores can withstand temperatures above 80°C. Understanding the sporulation process not only sheds light on bacterial survival strategies but also informs strategies for harnessing B. subtilis in biotechnology, from biofertilizers to biopreservatives.

Reviving Ancient Traditions: Rebuilding a Tribal Hut in Spore

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Key components and layers of B. subtilis spores for survival

Bacillus subtilis, a Gram-positive bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores, often referred to as spores. These structures are not merely dormant forms but are survival capsules engineered to withstand extreme conditions. The spore’s architecture is a marvel of biological design, comprising distinct layers and components that collectively ensure longevity and resilience. Understanding this structure is crucial for applications in biotechnology, medicine, and environmental science.

At the core of the B. subtilis spore lies the core wall, a modified peptidoglycan layer that maintains the spore’s shape and protects the genetic material. Within this core resides the nucleoid, a compact, dehydrated DNA molecule stabilized by small acid-soluble proteins (SASPs). These SASPs not only shield the DNA from damage but also contribute to the spore’s resistance to heat, radiation, and desiccation. Surrounding the core is the cortex, a thick layer of peptidoglycan that is partially degraded during germination, providing the energy and structural changes needed for revival. This layer’s cross-linked structure is critical for withstanding mechanical stress and enzymatic attacks.

Encasing the cortex is the spore coat, a proteinaceous layer composed of over 70 different proteins arranged in an inner and outer coat. The coat acts as a barrier against environmental stressors, including chemicals, enzymes, and physical abrasion. Its hydrophobic nature also prevents water uptake, further enhancing desiccation resistance. Notably, the coat’s proteins are highly cross-linked, forming a rigid yet flexible armor. For instance, the CotA protein, a heme-containing oxidase, contributes to the coat’s structural integrity and protects against oxidative damage.

The outermost layer, the exosporium, is a thin, hair-like structure that envelops the entire spore. This layer is often likened to a protective skin, shielding the spore from external threats while allowing for surface attachment and interaction with the environment. The exosporium is studded with glycoproteins and lipids, which play roles in spore dispersal, immune evasion, and environmental sensing. Its presence is particularly significant in soil-dwelling bacteria like B. subtilis, where it aids in survival amidst fluctuating conditions.

Practical applications of spore structure knowledge are vast. For instance, in biotechnology, spores are used as delivery vehicles for enzymes and vaccines due to their stability. Understanding the coat’s protein composition allows for genetic engineering to enhance spore functionality, such as improving adhesion to surfaces or increasing resistance to specific stressors. In medicine, spore structure insights inform the development of antimicrobial strategies targeting spore germination. For example, disrupting the cortex layer’s integrity can prevent spore revival, a tactic explored in combating spore-forming pathogens like Bacillus anthracis.

In summary, the B. subtilis spore’s structure is a testament to evolutionary ingenuity, with each layer and component serving a specific survival function. From the DNA-protecting core to the environmentally interactive exosporium, every element contributes to the spore’s remarkable resilience. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of microbial survival strategies but also unlocks practical applications across industries, making spore biology a field of enduring relevance.

Freezing and C. Diff: Does Cold Temperatures Kill Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore Germination: Conditions and triggers for B. subtilis spore revival

Bacillus subtilis, a well-known spore-forming bacterium, has mastered the art of survival through its ability to produce highly resistant endospores. These spores can remain dormant for years, withstanding extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. However, under the right circumstances, they can revive and resume growth, a process known as spore germination. Understanding the conditions and triggers for B. subtilis spore revival is crucial for applications in biotechnology, food safety, and environmental science.

Analytical Perspective: Spore germination in B. subtilis is a complex, multi-step process initiated by specific nutrients and environmental cues. The primary triggers include the presence of certain amino acids, particularly L-valine, and purine nucleosides like inosine and guanosine. These germinants bind to specific receptors on the spore’s surface, triggering a cascade of events that lead to the activation of metabolic pathways and the breakdown of the spore’s protective layers. For instance, a study published in *Journal of Bacteriology* found that a concentration of 10 mM L-valine could induce germination in over 90% of B. subtilis spores within 30 minutes under optimal conditions (37°C, pH 7.5).

Instructive Approach: To induce spore germination in a laboratory setting, follow these steps: 1) Prepare a nutrient solution containing 10 mM L-valine and 1 mM inosine in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.5). 2) Suspend the B. subtilis spores in this solution at a concentration of 10^6 spores/mL. 3) Incubate the suspension at 37°C with gentle agitation. 4) Monitor germination progress using phase-contrast microscopy or by measuring the decrease in optical density (OD600) over time. Caution: Avoid using high temperatures (>50°C) or harsh chemicals, as these can damage the spores irreversibly.

Comparative Insight: Unlike other spore-forming bacteria, such as Clostridium botulinum, B. subtilis spores require specific germinants for revival. While C. botulinum spores can germinate in response to a broader range of nutrients, B. subtilis is more selective, relying heavily on amino acids and nucleosides. This specificity makes B. subtilis a valuable model for studying spore germination mechanisms and developing targeted strategies to control spore revival in industrial and clinical settings.

Descriptive Narrative: Imagine a dormant B. subtilis spore, encased in a rugged coat and waiting for the right moment to awaken. When a drop of nutrient-rich water containing L-valine reaches it, the spore’s receptors spring into action. The coat begins to degrade, and the core rehydrates, swelling like a seed after rain. Within minutes, the spore’s metabolic machinery restarts, and it transforms into a vegetative cell, ready to grow and multiply. This revival process is not just a biological curiosity but a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life.

Persuasive Argument: Harnessing the conditions for B. subtilis spore germination has practical implications. In biotechnology, controlled germination can enhance the production of enzymes and other bioactive compounds. In food safety, understanding these triggers helps develop strategies to prevent spore outgrowth in processed foods. For environmental scientists, studying spore revival mechanisms provides insights into bacterial survival in extreme habitats. By mastering these conditions, we can both exploit and control B. subtilis spores, turning their remarkable resilience into a tool for innovation and safety.

Play Spore on Mac: Compatibility Guide and Solutions

You may want to see also

Survival Advantages: Benefits of spore formation in B. subtilis for longevity

Bacillus subtilis, a ubiquitous bacterium, has mastered the art of survival through its remarkable ability to form spores. These spores are not just dormant cells but highly resilient structures that enable the bacterium to endure extreme conditions, ensuring its longevity in diverse environments.

The Spore Formation Process: A Strategic Retreat

In the face of adversity, B. subtilis initiates a complex transformation. As nutrients deplete or environmental stresses mount, the bacterium undergoes sporulation, a process akin to a strategic retreat. This involves the formation of a spore within the mother cell, which then lyses, releasing the spore. The spore's structure is a marvel of nature, comprising multiple layers, including a thick peptidoglycan cortex and a protective coat, all encased within an outer membrane. This intricate design is the key to its survival prowess.

Resisting the Odds: Spore Longevity

The benefits of spore formation are profound. Firstly, spores can withstand desiccation, a critical advantage in arid environments. This resistance allows B. subtilis to persist in soil and on surfaces for extended periods, waiting for favorable conditions to return. Moreover, spores are highly resistant to heat, radiation, and chemicals, including many disinfectants. For instance, spores can survive temperatures above 100°C, a feat achieved through the stabilization of their DNA and proteins. This extreme tolerance enables B. subtilis to endure sterilization processes, making it a challenge in food preservation and healthcare settings.

A Comparative Perspective: Spores vs. Vegetative Cells

Comparing spores to their vegetative counterparts highlights their superiority in survival. Vegetative cells, the active form of B. subtilis, are susceptible to environmental stresses, with limited tolerance to harsh conditions. In contrast, spores can remain viable for years, even decades, under adverse circumstances. This longevity is not just a passive resistance but an active state, as spores can sense environmental cues and revert to vegetative growth when conditions improve, ensuring the species' continuity.

Practical Implications and Applications

Understanding spore formation has practical implications. In agriculture, B. subtilis spores are used as biofertilizers and biocontrol agents, enhancing crop growth and protecting against pathogens. The spores' longevity ensures their effectiveness over extended periods, reducing the need for frequent applications. In the pharmaceutical industry, spore-forming capabilities are leveraged for probiotic supplements, where spores' stability ensures product viability during storage and passage through the digestive system. For instance, a daily dose of 1-2 billion spores of B. subtilis is recommended for gut health in adults, showcasing the practical benefits of spore formation.

In summary, spore formation in B. subtilis is a sophisticated survival strategy, offering unparalleled longevity and resistance. This process not only ensures the bacterium's persistence in diverse ecosystems but also provides valuable applications in various industries, highlighting the practical significance of understanding and harnessing this natural phenomenon.

Mastering Spore: Unlocking Every Feature for Ultimate Gameplay Experience

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Factors like nutrient depletion inducing spore formation in B. subtilis

Bacillus subtilis, a ubiquitous soil bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores under adverse conditions. One of the most critical environmental triggers for spore formation is nutrient depletion. When essential resources like carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus become scarce, B. subtilis initiates a complex developmental program to ensure survival. This process, known as sporulation, is a remarkable adaptation that allows the bacterium to endure extreme environments, including desiccation, heat, and chemical stress.

The mechanism by which nutrient depletion induces sporulation is tightly regulated by a network of signaling pathways. For instance, the depletion of amino acids activates the Spo0A transcription factor, a master regulator of sporulation. Spo0A responds to signals from multiple pathways, including the kinase-phosphatase system, which monitors nutrient availability. When nutrients are abundant, phosphatases keep Spo0A inactive; however, under starvation conditions, kinases phosphorylate Spo0A, triggering the expression of genes required for spore formation. This regulatory system ensures that B. subtilis commits to sporulation only when survival is threatened.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in industrial and laboratory settings. For example, to induce spore formation in B. subtilis cultures, researchers often use defined minimal media lacking key nutrients like glucose or ammonium salts. Typically, a culture grown in rich LB broth (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl) is transferred to a minimal medium (e.g., Spizizen’s minimal medium with 0.5% glucose and 0.2% ammonium sulfate) and incubated for 24–48 hours at 37°C. This nutrient-limited environment reliably triggers sporulation, with spore yields reaching up to 10^8 spores per mL under optimized conditions.

Comparatively, nutrient depletion in B. subtilis contrasts with other spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium spp., which often require additional triggers such as oxygen limitation. This highlights the unique adaptability of B. subtilis, which can respond to nutrient scarcity alone. For instance, while Clostridium botulinum requires anaerobic conditions to sporulate, B. subtilis can initiate sporulation aerobically in the absence of nutrients. This distinction underscores the versatility of B. subtilis as a model organism for studying stress responses.

In conclusion, nutrient depletion serves as a potent environmental trigger for spore formation in B. subtilis, driven by a sophisticated regulatory network centered on Spo0A. Understanding this process not only sheds light on bacterial survival strategies but also informs practical applications in biotechnology, such as spore production for probiotics or biocontrol agents. By manipulating nutrient availability, researchers can harness the natural resilience of B. subtilis, turning environmental stress into a tool for innovation.

Can Mold Spores Contaminate Your Clothes? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Bacillus subtilis is a well-known spore-forming bacterium.

Bacillus subtilis forms spores in response to nutrient depletion, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources, as a survival mechanism.

Yes, Bacillus subtilis spores are highly resistant to extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, allowing them to survive for long periods.

Yes, under favorable conditions, Bacillus subtilis spores can germinate and return to their vegetative, actively growing state.