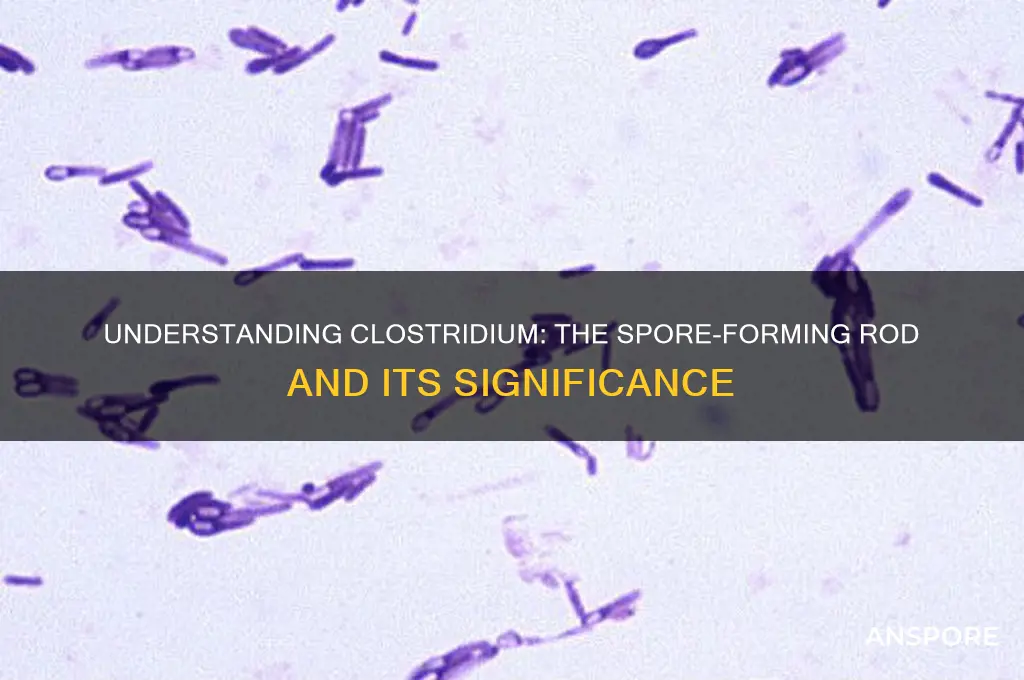

Clostridium is a genus of Gram-positive, anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria that are widely recognized for their ability to form highly resistant endospores, commonly referred to as spores. These spores allow Clostridium species to survive in harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to disinfectants, making them ubiquitous in soil, water, and the gastrointestinal tracts of animals and humans. The spore-forming capability is a defining characteristic of Clostridium, distinguishing it from many other bacterial genera and contributing to its significance in both medical and environmental contexts. Understanding whether Clostridium is a spore-forming rod is essential for comprehending its pathogenic potential, ecological role, and the challenges associated with its control and eradication.

What You'll Learn

- Clostridium Characteristics: Gram-positive, anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria known for spore formation and toxin production

- Spore Formation Process: Endospore development under stress, ensuring survival in harsh environments like heat and chemicals

- Species Diversity: Includes *C. botulinum*, *C. difficile*, and *C. tetani*, each causing distinct diseases

- Clinical Significance: Spores resist disinfection, leading to infections like botulism, tetanus, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Laboratory Identification: Detected via culture, staining, and molecular methods to confirm spore-forming rod morphology

Clostridium Characteristics: Gram-positive, anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria known for spore formation and toxin production

Clostridium species are gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria that thrive in anaerobic environments, meaning they do not require oxygen for growth. This characteristic makes them particularly adept at surviving in oxygen-depleted settings, such as soil, sediment, and the human gastrointestinal tract. Their gram-positive cell wall structure, composed primarily of a thick peptidoglycan layer, provides structural integrity and contributes to their resistance to certain environmental stresses. However, it is their ability to form highly resilient spores that sets them apart from many other bacterial genera. These spores can withstand extreme conditions, including heat, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals, ensuring the bacteria's survival in harsh environments.

One of the most notable features of Clostridium is its spore-forming capability, a process triggered by nutrient deprivation or other adverse conditions. Sporulation involves the differentiation of a vegetative cell into a spore, which is encased in a protective protein coat and can remain dormant for years. This adaptability allows Clostridium to persist in diverse ecosystems and poses challenges in clinical and industrial settings, as spores are notoriously difficult to eradicate. For instance, in healthcare, Clostridium spores can contaminate medical equipment and surfaces, necessitating rigorous sterilization protocols, such as autoclaving at 121°C for at least 15 minutes, to ensure complete inactivation.

Beyond their survival strategies, Clostridium species are infamous for producing potent toxins that contribute to severe human and animal diseases. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* produces botulinum toxin, one of the most lethal substances known, which causes botulism, a potentially fatal paralytic illness. Similarly, *Clostridium difficile* secretes toxins A and B, leading to antibiotic-associated diarrhea and life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis. These toxins act by disrupting cellular processes, such as nerve function or intestinal epithelial integrity, underscoring the clinical significance of Clostridium infections. Treatment often involves targeted antibiotics, like metronidazole or vancomycin for *C. difficile*, but must be carefully managed to avoid exacerbating toxin release.

Comparatively, while many bacteria produce toxins, Clostridium's combination of spore formation and toxin production makes it uniquely problematic. Unlike non-spore-forming pathogens, Clostridium can remain latent in the environment, only to cause disease when conditions become favorable. This dual threat necessitates a two-pronged approach to control: preventing spore germination and neutralizing toxin activity. For example, in food processing, combining heat treatment to destroy spores with toxin-binding agents, such as specific antibodies or activated charcoal, can mitigate the risk of contamination. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat Clostridium-related diseases and contamination.

Practically, individuals can reduce the risk of Clostridium infections by adopting simple yet effective measures. Proper food handling, including thorough cooking to temperatures above 75°C, can kill vegetative cells and spores. In healthcare settings, strict adherence to hand hygiene and isolation precautions for patients with *C. difficile* infections can limit transmission. For those prescribed antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum agents, discussing the risk of *C. difficile* infection with a healthcare provider and considering probiotic supplementation may help maintain gut flora balance. By recognizing the unique traits of Clostridium and implementing targeted interventions, both individuals and industries can minimize the impact of these resilient and toxigenic bacteria.

Install Spore Mods Easily: A Guide Without Game Assistant

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process: Endospore development under stress, ensuring survival in harsh environments like heat and chemicals

Clostridium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores under stress conditions. These endospores are not just dormant structures but are metabolically inactive, resilient forms that ensure survival in extreme environments such as high temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. The spore formation process, or sporulation, is a complex, multi-stage mechanism triggered when nutrients become scarce or environmental conditions turn hostile. This process is a testament to the bacterium's evolutionary ingenuity, allowing it to persist in settings where most other microorganisms would perish.

The sporulation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterial cell divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is not merely physical but also involves the partitioning of genetic material, ensuring the forespore retains a complete copy of the genome. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, creating a double-membrane structure. Within this protective envelope, the forespore undergoes a series of morphological and biochemical changes, including the synthesis of a thick, multi-layered spore coat and the deposition of calcium dipicolinate, a compound that stabilizes the spore's DNA. This stage is critical, as it equips the endospore with the ability to withstand temperatures up to 100°C and exposure to harsh chemicals like ethanol and hydrogen peroxide.

One of the most fascinating aspects of endospore development is its regulatory precision. The process is governed by a cascade of sigma factors, proteins that direct gene expression at specific stages of sporulation. For instance, sigma factor σ^H^ is activated early in the process, initiating the expression of genes required for the engulfment of the forespore. Later, sigma factors σ^E^, σ^G^, and σ^K^ take over, each controlling distinct phases of spore maturation. This tightly regulated sequence ensures that each step of sporulation occurs in the correct order, maximizing the spore's chances of survival.

Practical applications of understanding spore formation extend beyond microbiology. For example, in the food industry, Clostridium spores are a significant concern due to their heat resistance, which can survive pasteurization temperatures (typically 72°C for 15 seconds). To ensure food safety, more aggressive methods like autoclaving (121°C for 15 minutes) are employed to destroy these spores. Similarly, in healthcare, Clostridium spores, particularly those of *Clostridium difficile*, pose a risk in hospital settings, necessitating stringent disinfection protocols using spore-specific chemicals like chlorine-based agents.

In conclusion, the spore formation process in Clostridium is a remarkable adaptation to environmental stress, showcasing the bacterium's ability to transform into a nearly indestructible form. By understanding the intricacies of endospore development, we can devise more effective strategies to control these organisms in various settings, from food processing to medical environments. This knowledge not only highlights the resilience of life but also underscores the importance of targeted interventions in managing microbial threats.

Surviving the Flames: Can Spores Endure Wildfires and Heat?

You may want to see also

Species Diversity: Includes *C. botulinum*, *C. difficile*, and *C. tetani*, each causing distinct diseases

The genus *Clostridium* encompasses a diverse array of spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria, many of which are pathogenic to humans. Among these, *C. botulinum*, *C. difficile*, and *C. tetani* stand out for their ability to cause distinct and severe diseases. Each species has evolved unique mechanisms to exploit human vulnerabilities, making them significant public health concerns. Understanding their differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

Consider *C. botulinum*, the causative agent of botulism, a potentially fatal disease characterized by muscle paralysis. This bacterium produces one of the most potent toxins known to science, botulinum neurotoxin. Ingesting as little as 0.000001 grams of this toxin can be lethal. It thrives in anaerobic environments, such as improperly canned foods or contaminated soil. Infants are particularly susceptible to intestinal botulism, where spores germinate in the gut, producing toxin in situ. Prevention hinges on proper food handling—boiling home-canned foods for 10 minutes before consumption and avoiding honey in children under one year old.

In contrast, *C. difficile* is a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis, primarily affecting hospitalized or immunocompromised individuals. This species exploits disruptions in the gut microbiome caused by broad-spectrum antibiotics, allowing it to colonize and produce toxins A and B. Symptoms range from mild diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation. Treatment often involves discontinuing the offending antibiotic and administering narrow-spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin or fidaxomicin. Probiotics, particularly *Saccharomyces boulardii*, may aid in restoring gut flora balance. Hand hygiene and isolation precautions are critical in healthcare settings to prevent transmission.

C. tetani, the etiological agent of tetanus, takes a different approach. Its spores are ubiquitous in soil and can enter the body through wounds, where they germinate and produce tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin that causes painful muscle contractions. Unlike the other two species, C. tetani does not require a gut environment to cause disease. Tetanus is preventable through vaccination, with the DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) vaccine recommended for children and booster shots every 10 years for adults. Wound care is essential—cleaning injuries thoroughly and seeking medical attention for deep or dirty wounds can prevent spore germination.

These three *Clostridium* species exemplify the genus’s adaptability and pathogenic potential. While *C. botulinum* and *C. difficile* exploit the gastrointestinal tract, *C. tetani* targets the nervous system. Their distinct disease mechanisms underscore the importance of tailored prevention strategies, from food safety and antibiotic stewardship to vaccination and wound management. Recognizing their differences empowers healthcare professionals and the public to mitigate risks effectively.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Crafting Liquid Culture from Spores

You may want to see also

Clinical Significance: Spores resist disinfection, leading to infections like botulism, tetanus, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea

Clostridium species are notorious for their ability to form highly resistant spores, a trait that significantly impacts their clinical relevance. These spores are not just a survival mechanism for the bacteria; they are a formidable challenge in healthcare settings. The resilience of Clostridium spores to disinfection methods is a critical factor in the persistence and spread of infections, making them a silent yet potent threat in hospitals and communities alike.

The Disinfection Dilemma: Standard disinfection protocols often fall short when confronted with Clostridium spores. These spores can withstand extreme conditions, including high temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to many common disinfectants. For instance, a study comparing the efficacy of various disinfectants against Clostridium difficile spores revealed that even prolonged exposure to 10% bleach solution, a potent disinfectant, failed to achieve complete spore eradication. This resistance is attributed to the spore's unique structure, featuring a thick protein coat and a highly impermeable outer layer, which acts as an effective barrier against external threats.

Infections Unveiled: The clinical implications of this spore resistance are far-reaching, manifesting in several severe infections. Botulism, caused by Clostridium botulinum, is a potentially fatal disease characterized by muscle paralysis. The spores of this bacterium can contaminate food, and their resistance to cooking temperatures allows them to survive in improperly processed canned foods. Tetanus, another spore-related infection, is caused by Clostridium tetani and is known for its severe muscle spasms. The spores of this bacterium are ubiquitous in soil, and their ability to persist in the environment contributes to the risk of infection through wounds. Furthermore, Clostridium difficile is a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, particularly in healthcare settings. Its spores can survive on surfaces for extended periods, facilitating transmission and making infection control a daunting task.

Prevention and Control Strategies: Given the challenges posed by spore-forming Clostridium species, infection prevention and control require a multifaceted approach. In healthcare facilities, stringent environmental cleaning and disinfection protocols are essential. This includes the use of sporicidal agents, such as chlorine dioxide or hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants, which have demonstrated efficacy against Clostridium spores. For food-related botulism prevention, proper canning techniques, including adequate heating to destroy spores, are crucial. Public health education plays a vital role in raising awareness about the risks associated with home-canned foods and the importance of wound care to prevent tetanus.

Antibiotic Stewardship: The rise of antibiotic-associated diarrhea caused by C. difficile highlights the importance of judicious antibiotic use. Prolonged or inappropriate antibiotic therapy disrupts the normal gut flora, allowing C. difficile to proliferate and cause disease. Healthcare providers must adhere to antibiotic prescribing guidelines, ensuring that these medications are used only when necessary and for the shortest effective duration. This approach not only reduces the risk of C. difficile infections but also helps combat the broader issue of antibiotic resistance. In cases where C. difficile infection occurs, specific antibiotics like fidaxomicin or vancomycin are used, targeting the bacterium while minimizing further disruption to the gut microbiome.

Understanding the clinical significance of spore-forming Clostridium species is essential for healthcare professionals and the public alike. The ability of these spores to resist disinfection underscores the need for tailored infection control measures, from enhanced cleaning protocols to responsible antibiotic use. By addressing these challenges, we can mitigate the impact of Clostridium-related infections and improve patient outcomes. This knowledge is a powerful tool in the ongoing battle against these resilient bacterial adversaries.

Listeria Spores: Unraveling the Truth About Their Formation and Risks

You may want to see also

Laboratory Identification: Detected via culture, staining, and molecular methods to confirm spore-forming rod morphology

Clostridium species are notorious for their ability to form highly resistant spores, a characteristic that complicates their detection and identification in clinical and environmental samples. Laboratory identification of these spore-forming rods relies on a combination of culture, staining, and molecular methods, each offering unique insights into their morphology and genetic makeup. This multi-pronged approach ensures accurate identification, which is critical for diagnosing infections such as Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea or gas gangrene caused by Clostridium perfringens.

Culture Methods: The Foundation of Identification

Culturing Clostridium species begins with creating an anaerobic environment, as these organisms are obligate anaerobes. Selective media like blood agar or egg yolk agar are commonly used, with the latter aiding in the detection of lecithinase activity, a hallmark of C. perfringens. Sporulation can be induced by extending incubation times (up to 7 days) at 37°C. A key observation is the formation of dull, gritty colonies, which, when examined microscopically, reveal the characteristic rod-shaped morphology. For C. difficile, cycloserine-cefoxitin-fructose agar (CCFA) is preferred, as it inhibits non-C. difficile flora while promoting the growth of target organisms.

Staining Techniques: Visual Confirmation of Morphology

Gram staining is the initial step, typically revealing Gram-positive rods, though some species may appear Gram-variable due to spore formation. The presence of oval or spherical spores, often terminally or subterminally located, is confirmed using specialized stains like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain. This method employs malachite green to penetrate spores, followed by counterstaining with safranin. Under 1000x magnification, the spores appear green against the red vegetative cells, providing visual confirmation of spore-forming capability.

Molecular Methods: Precision in Identification

While culture and staining offer morphological evidence, molecular methods provide definitive identification. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting 16S rRNA genes or toxin-encoding genes (e.g., *tcdA* and *tcdB* for C. difficile) is highly sensitive and specific. For instance, PCR assays can detect as few as 10^3 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL of C. difficile in stool samples, making it invaluable for rapid diagnosis. DNA sequencing of the *rpoB* gene or multilocus sequence typing (MLST) further differentiates between closely related species, ensuring accurate taxonomic placement.

Practical Tips and Cautions

When working with Clostridium species, strict anaerobic conditions are non-negotiable; even brief exposure to oxygen can inhibit growth. For staining, ensure slides are heat-fixed to prevent spore loss during washing. In molecular assays, DNA extraction must be optimized to break spore walls, often requiring mechanical lysis or extended incubation with lysozyme. Cross-contamination is a risk, particularly with C. difficile, so dedicated lab spaces and stringent decontamination protocols (e.g., 10% bleach for surfaces) are essential.

The identification of Clostridium as a spore-forming rod demands a synergistic use of culture, staining, and molecular methods. Each technique complements the others, addressing their respective limitations. Culture provides phenotypic evidence, staining offers morphological confirmation, and molecular methods deliver genetic precision. Together, they form a robust framework for accurate identification, enabling timely diagnosis and effective management of Clostridium-related infections.

Mastering Spore Collection: Tips to Unlock All Parts Efficiently

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Clostridium is a genus of Gram-positive, spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria.

Clostridium forms spores in response to unfavorable environmental conditions, such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or exposure to toxins.

Yes, all species within the Clostridium genus are capable of forming spores as part of their life cycle.