Fungi exhibit remarkable diversity in their reproductive strategies, employing both sexual and asexual methods depending on environmental conditions and species. While some fungi primarily reproduce asexually through spores or fragmentation, others engage in sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of gametes and genetic recombination. This dual capability allows fungi to adapt to changing environments, ensuring survival and genetic diversity. Understanding whether fungi reproduce sexually or asexually is crucial for fields like mycology, ecology, and biotechnology, as it sheds light on their life cycles, evolutionary mechanisms, and ecological roles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Modes | Fungi can reproduce both sexually and asexually, depending on the species and environmental conditions. |

| Sexual Reproduction | Involves the fusion of gametes (e.g., hyphae from different individuals) to form a zygote, followed by meiosis. Examples include spore formation (e.g., basidiospores, asci). |

| Asexual Reproduction | Involves vegetative growth or spore production without gamete fusion. Examples include fragmentation, budding, and spore formation (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores). |

| Life Cycle | Many fungi exhibit alternation of generations, switching between sexual (meiosis) and asexual (mitosis) phases. |

| Environmental Triggers | Sexual reproduction often occurs under stressful conditions (e.g., nutrient depletion), while asexual reproduction is more common in favorable environments. |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual reproduction promotes genetic diversity through recombination, while asexual reproduction maintains clonal populations. |

| Examples | Sexual: Mushrooms (Basidiomycetes), Yeasts (during mating). Asexual: Molds (e.g., Penicillium), Yeasts (budding). |

| Dominant Mode | Asexual reproduction is more common in nature due to its efficiency, but sexual reproduction ensures long-term survival and adaptation. |

Explore related products

$17.86 $21.95

What You'll Learn

- Fungal Reproduction Methods: Overview of sexual and asexual reproduction mechanisms in fungi

- Sexual Spores in Fungi: Role of gametes and spores in fungal sexual reproduction

- Asexual Spores in Fungi: Types of asexual spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores)

- Environmental Factors: How environment influences sexual vs. asexual reproduction in fungi

- Fungal Life Cycles: Comparison of sexual and asexual phases in fungal life cycles

Fungal Reproduction Methods: Overview of sexual and asexual reproduction mechanisms in fungi

Fungi exhibit a remarkable diversity in their reproductive strategies, employing both sexual and asexual methods to ensure survival and adaptation. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; many fungal species alternate between the two depending on environmental conditions. Sexual reproduction involves the fusion of gametes, leading to genetic recombination and the formation of spores, such as asci or basidia. This process enhances genetic diversity, a critical factor in adapting to changing environments. For example, the common baker’s yeast (*Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) undergoes sexual reproduction through a process called sporulation, producing four haploid spores within an ascus. In contrast, asexual reproduction, which includes methods like budding, fragmentation, and spore formation (e.g., conidia), allows for rapid proliferation without genetic variation. This is particularly advantageous in stable environments where quick colonization is key. Understanding these mechanisms provides insight into fungal ecology, from their role in nutrient cycling to their impact on human health and agriculture.

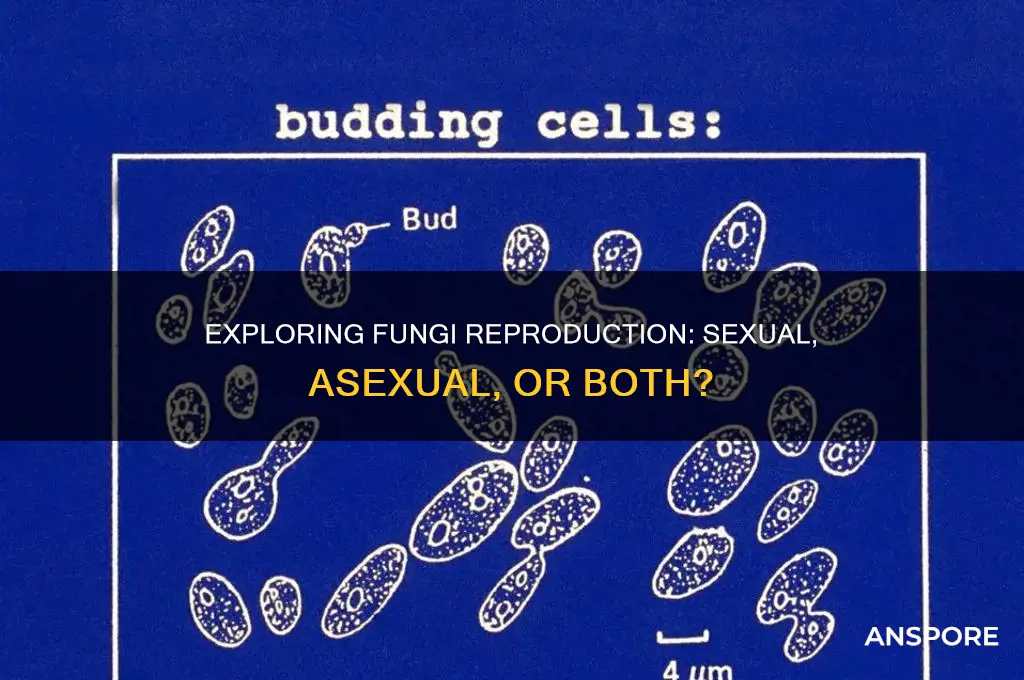

Consider the asexual reproduction method of budding, a process exemplified by *Candida albicans*, a fungus commonly found in the human microbiome. Here, a small outgrowth (bud) forms on the parent cell, eventually detaching to become a new individual. This method is efficient and rapid, enabling *C. albicans* to colonize host tissues quickly. However, it lacks genetic diversity, making the population vulnerable to environmental changes or antifungal treatments. To counteract this limitation, some fungi, like *Aspergillus*, employ both asexual (conidia) and sexual (cleistothecia) reproduction. Conidia, produced in vast quantities, disperse easily through air or water, facilitating colonization of new habitats. Meanwhile, sexual reproduction ensures genetic reshuffling, which can lead to the emergence of resistant strains. This dual strategy highlights the adaptability of fungi, allowing them to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

For those studying or managing fungal populations, recognizing the reproductive method is crucial. Asexual reproduction can be identified by the presence of structures like conidia or hyphae fragmentation, while sexual reproduction often involves more complex structures like fruiting bodies or asci. Practical tips include observing spore morphology under a microscope or using molecular techniques to detect mating-type genes. For instance, in agricultural settings, identifying asexual spores of *Fusarium* can help implement timely fungicide applications, whereas understanding the sexual cycle of *Magnaporthe oryzae* (rice blast fungus) can inform crop rotation strategies. Age categories of fungal colonies can also provide clues: younger colonies often favor asexual reproduction for rapid growth, while older colonies may shift to sexual reproduction under stress.

A comparative analysis reveals that sexual reproduction, while slower, offers long-term benefits by generating genetic diversity, which is essential for survival in unpredictable environments. Asexual reproduction, on the other hand, provides short-term advantages, such as rapid colonization and resource exploitation. This trade-off is evident in species like *Neurospora crassa*, which alternates between asexual conidia production and sexual reproduction via meiosis. The choice of method often depends on factors like nutrient availability, temperature, and pH. For example, *Penicillium* species produce conidia in nutrient-rich conditions but may shift to sexual reproduction when resources are scarce. This adaptability underscores the evolutionary success of fungi, making them one of the most widespread and resilient organisms on Earth.

In conclusion, fungal reproduction methods are a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By mastering both sexual and asexual strategies, fungi navigate diverse environments with precision. Whether through the rapid spread of conidia or the genetic innovation of meiosis, these mechanisms ensure their persistence. For researchers, farmers, and medical professionals, understanding these processes is not just academic—it’s practical. From combating fungal diseases to harnessing fungi for biotechnology, knowledge of their reproductive methods unlocks solutions to real-world challenges. By observing, analyzing, and applying this knowledge, we can better coexist with these ubiquitous organisms.

Mastering Spore Syringe Creation: A Step-by-Step DIY Guide

You may want to see also

Sexual Spores in Fungi: Role of gametes and spores in fungal sexual reproduction

Fungi exhibit a remarkable diversity in their reproductive strategies, blending both sexual and asexual methods to ensure survival across varying environments. While asexual reproduction through spores like conidia allows for rapid proliferation, sexual reproduction introduces genetic diversity, a critical advantage in adapting to changing conditions. Central to this process are sexual spores, specialized structures that encapsulate the fusion of gametes, marking the culmination of fungal sexual reproduction.

Consider the lifecycle of the common mushroom, *Agaricus bisporus*. Here, sexual reproduction begins with the fusion of haploid hyphae from two compatible individuals, forming a diploid zygote. This zygote develops into a structure called a basidium, which undergoes meiosis to produce haploid basidiospores. These spores, dispersed by wind or water, germinate into new haploid mycelia, perpetuating the cycle. The role of gametes in this process is pivotal: they ensure genetic recombination, a mechanism that fosters adaptability by shuffling genetic material. Without this step, fungi would lack the evolutionary flexibility to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Analyzing the broader implications, sexual spores serve as a reservoir of genetic variation, enabling fungi to resist diseases, tolerate environmental stresses, and exploit new ecological niches. For instance, in agricultural settings, the sexual spores of *Fusarium* species can lead to crop infections, but understanding their lifecycle allows for targeted interventions. Farmers can disrupt spore dispersal by adjusting irrigation practices or using fungicides at critical stages, reducing the risk of infection. This underscores the practical importance of recognizing the role of sexual spores in fungal reproduction.

A comparative perspective highlights the efficiency of sexual spores versus asexual methods. Asexual spores, like conidia, are produced rapidly and in large quantities, ideal for colonizing stable environments. Sexual spores, however, are fewer and require more energy to produce, but their genetic diversity ensures long-term survival. For example, in the chestnut blight fungus *Cryphonectria parasitica*, sexual reproduction has enabled the emergence of resistant strains, offering hope for the recovery of chestnut forests. This contrast illustrates the complementary roles of sexual and asexual spores in fungal lifecycles.

In conclusion, sexual spores in fungi are not merely reproductive endpoints but dynamic agents of genetic innovation. By facilitating the fusion of gametes and encapsulating the products of meiosis, they ensure fungi’s resilience and adaptability. Whether in natural ecosystems or agricultural contexts, understanding their role provides actionable insights for managing fungal populations and leveraging their ecological contributions.

UV Light's Power: Can It Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Asexual Spores in Fungi: Types of asexual spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores)

Fungi exhibit remarkable versatility in reproduction, employing both sexual and asexual strategies to thrive in diverse environments. Among asexual methods, spore production stands out as a key mechanism for dispersal and survival. Asexual spores, unlike their sexual counterparts, are produced by a single parent without the fusion of gametes, ensuring rapid proliferation under favorable conditions. This efficiency makes asexual spores critical for fungal colonization and persistence, particularly in stable ecosystems. Understanding the types and functions of these spores—such as conidia and sporangiospores—sheds light on fungal ecology and their impact on agriculture, medicine, and industry.

Conidia, perhaps the most recognizable asexual spores, are produced at the tips or sides of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. These spores are typically single-celled, dry, and lightweight, enabling wind or water dispersal. For example, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* genera rely heavily on conidia for propagation. In agricultural settings, conidia from *Botrytis cinerea* (gray mold) can devastate crops like grapes and tomatoes, highlighting their role in plant pathology. To mitigate conidia-driven infections, farmers often employ fungicides such as chlorothalonil or sulfur, applied preventatively at rates of 2–4 pounds per acre, depending on crop density and disease pressure.

Sporangiospores, in contrast, develop within a sporangium, a sac-like structure formed at the end of a sporangiophore. These spores are often wet at maturity and are released en masse, relying on rain splash or insect vectors for dispersal. *Phycomyces* and *Pilobolus* are classic examples, with the latter exhibiting a unique mechanism: spores are ejected with force, sometimes traveling several feet. In indoor environments, sporangiospores from *Mucor* and *Rhizopus* can contaminate damp materials, posing risks to immunocompromised individuals. Remediation involves reducing humidity below 50% and using HEPA filters to capture airborne spores, coupled with prompt removal of moldy substrates.

While conidia and sporangiospores dominate discussions of asexual spores, other types like chlamydospores and blastospores warrant attention. Chlamydospores, produced by fungi such as *Fusarium* and *Candida*, are thick-walled and serve as survival structures in harsh conditions. Blastospores, seen in yeasts like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, bud off from parent cells and are pivotal in fermentation processes. For instance, in brewing, controlling temperature (15–25°C) and sugar concentration (10–20%) optimizes blastospore production, ensuring consistent alcohol yields.

In summary, asexual spores in fungi are diverse in form and function, each adapted to specific ecological niches. Conidia and sporangiospores exemplify the range of dispersal strategies, while chlamydospores and blastospores underscore survival and industrial relevance. Recognizing these distinctions not only advances mycological research but also informs practical applications, from disease management to biotechnology. Whether in the field or lab, understanding these spores empowers us to harness or counteract their effects effectively.

Can Alcohol Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores? Facts and Myths Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: How environment influences sexual vs. asexual reproduction in fungi

Fungi, like many organisms, exhibit a remarkable adaptability in their reproductive strategies, shifting between sexual and asexual methods based on environmental cues. This flexibility is not random but a finely tuned response to their surroundings, ensuring survival and propagation under varying conditions. For instance, nutrient availability plays a pivotal role. In environments rich in resources, fungi often favor asexual reproduction, such as budding or spore formation, which allows for rapid proliferation. Conversely, nutrient scarcity can trigger sexual reproduction, as seen in the formation of fruiting bodies in mushrooms, which require more energy but offer genetic diversity—a hedge against unpredictable environments.

Temperature and humidity are equally critical in dictating fungal reproductive modes. Many fungi thrive in specific temperature ranges, with deviations prompting a shift in strategy. For example, certain species of *Aspergillus* switch to sexual reproduction under cooler temperatures, while warmer conditions may favor asexual spore production. Humidity levels also influence this decision-making process. High moisture environments often encourage asexual reproduction, as spores can easily disperse and germinate. In drier conditions, fungi may prioritize sexual reproduction to produce more resilient structures, like sclerotia, which can withstand harsher conditions.

Light exposure, though often overlooked, is another environmental factor that shapes fungal reproduction. Some fungi, such as *Neurospora crassa*, are highly sensitive to light, which can induce sexual reproduction by triggering the development of reproductive structures like perithecia. This response is thought to be an adaptation to surface environments where light exposure is common. In contrast, fungi in darker environments, like soil or decaying wood, may rely more on asexual methods, as light-induced cues are absent.

Practical considerations for manipulating these environmental factors can be valuable in agriculture, biotechnology, and conservation. For instance, farmers cultivating edible fungi like shiitake mushrooms can control temperature and humidity to optimize yield. Maintaining a temperature range of 18–24°C (64–75°F) and humidity above 85% encourages asexual spore production, ideal for rapid growth. Conversely, introducing cooler temperatures (10–15°C or 50–59°F) and reducing humidity can stimulate sexual reproduction, beneficial for breeding programs aiming to develop new strains.

In conclusion, the environment acts as a master conductor, orchestrating the reproductive symphony of fungi. By understanding these influences, we can not only appreciate the ecological roles of fungi but also harness their potential in various applications. Whether through controlled laboratory conditions or natural habitat management, manipulating environmental factors offers a powerful tool for steering fungal reproduction toward desired outcomes.

Optimal Timing for Planting Morel Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Fungal Life Cycles: Comparison of sexual and asexual phases in fungal life cycles

Fungi exhibit remarkable adaptability in their life cycles, employing both sexual and asexual reproduction strategies to thrive in diverse environments. Understanding the phases of these cycles reveals how fungi balance genetic diversity with rapid proliferation. Asexual reproduction, characterized by processes like budding, fragmentation, and spore formation, allows fungi to multiply quickly under favorable conditions. For instance, yeast (a unicellular fungus) reproduces asexually through budding, where a small outgrowth (bud) develops and eventually detaches to form a new individual. This method ensures swift colonization but limits genetic variation, making populations vulnerable to environmental changes.

In contrast, sexual reproduction in fungi introduces genetic diversity, a critical advantage in unpredictable environments. This phase involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) to form a diploid zygote, followed by meiosis to restore the haploid state. For example, mushrooms (basidiomycetes) produce basidiospores through sexual reproduction, which disperse widely to colonize new habitats. The sexual phase is often triggered by stress, such as nutrient depletion or temperature shifts, ensuring survival through adaptation. However, it is energetically costly and time-consuming compared to asexual methods.

Comparing these phases highlights their complementary roles. Asexual reproduction dominates in stable environments, enabling fungi to exploit resources efficiently. Sexual reproduction, though less frequent, is essential for long-term survival, as it generates genetic diversity to combat pathogens and environmental challenges. For instance, the fungus *Neurospora crassa* alternates between asexual conidia production and sexual reproduction, depending on environmental cues. This duality underscores fungi’s evolutionary success.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in agriculture and medicine. Farmers manipulate fungal life cycles to control crop diseases, favoring asexual phases in beneficial fungi like mycorrhizae for rapid soil colonization. Conversely, disrupting sexual reproduction in pathogenic fungi, such as *Aspergillus* or *Candida*, can limit their adaptability and virulence. Understanding these cycles also aids in biotechnology, where fungi are engineered for asexual spore production to enhance enzyme or antibiotic yields.

In summary, the sexual and asexual phases of fungal life cycles are not mutually exclusive but interconnected strategies. Asexual reproduction ensures rapid growth and resource utilization, while sexual reproduction fosters resilience through genetic recombination. By studying these phases, scientists and practitioners can harness fungi’s potential while mitigating their harmful impacts, illustrating the profound implications of these microscopic life cycles on ecosystems and human endeavors.

Optimal Autoclave Spore Testing Frequency for Reliable Sterilization Results

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi can reproduce both sexually and asexually, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Fungi reproduce asexually through methods like spore formation (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores), budding, or fragmentation, which allow for rapid multiplication without the need for a mate.

Fungi reproduce sexually by fusing compatible hyphae (somatogamy) or gametes, followed by the formation of specialized structures like asci or basidia, which produce sexual spores (ascospores or basidiospores).