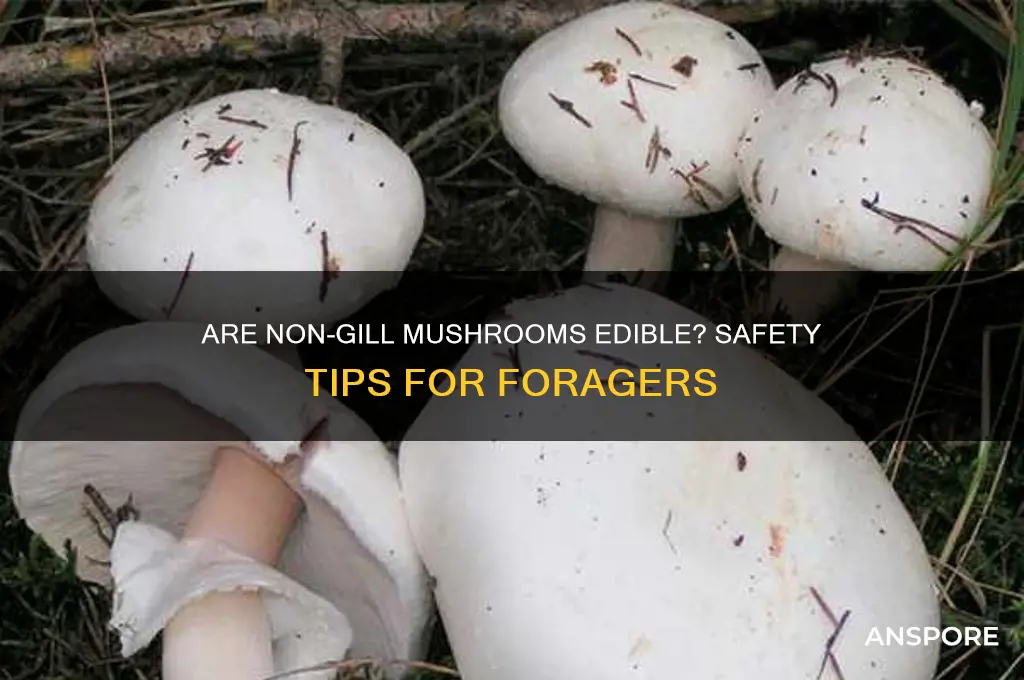

Non-gill mushrooms, which include varieties like puffballs, chanterelles, and morels, are a diverse group of fungi that lack the typical gill structure found in many common mushrooms. While some non-gill mushrooms are safe and highly prized for their culinary uses, such as the delicate flavor of chanterelles or the earthy richness of morels, others can be toxic or even deadly. Identifying these mushrooms accurately is crucial, as some poisonous species, like certain amanitas, may resemble edible varieties. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or fatalities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Non-gill mushrooms vary widely in edibility. Some are safe to eat (e.g., chanterelles, morels), while others are toxic or poisonous (e.g., Amanita species). |

| Identification | Proper identification is crucial. Non-gill mushrooms lack gills and may have pores, spines, or other structures (e.g., boletes, puffballs, coral fungi). |

| Toxic Species | Some non-gill mushrooms contain toxins (e.g., Amanita bisporigera, Amanita ocreata) that can cause severe illness or death. |

| Safe Species | Edible non-gill mushrooms include chanterelles, morels, lion's mane, and some boletes (e.g., Boletus edulis). |

| Preparation | Proper cooking is essential for some edible non-gill mushrooms (e.g., morels should always be cooked to destroy toxins). |

| Allergies | Some individuals may experience allergic reactions to certain mushrooms, regardless of their edibility. |

| Foraging Risks | Misidentification is a significant risk. Always consult a reliable guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms. |

| Conservation | Overharvesting can harm ecosystems. Practice sustainable foraging and avoid picking endangered species. |

| Seasonality | Many non-gill mushrooms are seasonal. For example, morels typically appear in spring, while chanterelles are more common in late summer to fall. |

| Habitat | Non-gill mushrooms grow in various habitats, including forests, grasslands, and even on wood (e.g., oyster mushrooms). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Non-Gill Mushrooms

When identifying non-gill mushrooms, it's essential to understand that these fungi lack the typical gill structure found under the caps of many mushrooms. Instead, they may have pores, spines, or other unique features. Non-gill mushrooms belong to various families, including boletes, polypores, and puffballs, each with distinct characteristics that aid in identification. To determine if a non-gill mushroom is safe to eat, start by examining its physical traits, habitat, and any associated odors or colors.

One common type of non-gill mushroom is the bolete, which has a spongy layer of pores under its cap instead of gills. Boletes often have a fleshy stem and a cap that can range in color from brown to red or yellow. To identify edible boletes, look for species like the *Boletus edulis* (porcini), which has a whitish pore surface that turns brownish with age and a mild, pleasant smell. Avoid boletes with a reddish pore surface or those that stain blue when bruised, as these may be toxic. Always cross-reference with a reliable field guide or consult an expert, as some poisonous mushrooms resemble edible boletes.

Polypores are another group of non-gill mushrooms, characterized by their bracket-like or shelf-like structures that grow on wood. Most polypores are tough and inedible, but a few, like the *Laetiporus sulphureus* (chicken of the woods), are safe to eat when young and tender. Identify chicken of the woods by its bright orange to yellow fan-shaped clusters and its growth on hardwood trees. Ensure it is free from insects and cook it thoroughly, as it can be tough if not prepared properly. Avoid polypores with white or pale undersides, as some of these can be toxic.

Puffballs are non-gill mushrooms that release spores through a hole or by breaking open when mature. Young, solid puffballs like the *Calvatia gigantea* (giant puffball) are edible and have a texture similar to tofu. To identify a safe puffball, cut it open to ensure the interior is pure white and free of gills or structures. Avoid older puffballs that have turned yellowish or greenish inside, as these are no longer safe to eat. Additionally, never consume a puffball without proper identification, as some poisonous mushrooms, like the Amanita species, can resemble puffballs in their early stages.

Lastly, always consider the habitat and season when identifying non-gill mushrooms. Edible species often grow in specific environments, such as boletes in forested areas or puffballs in grassy fields. Be cautious of mushrooms growing near polluted areas or treated lawns, as they can absorb toxins. If you are unsure about a mushroom's identity, do not consume it. Proper identification is crucial for safety, and when in doubt, consult a mycologist or experienced forager. Remember, while some non-gill mushrooms are delicious and safe, misidentification can lead to serious health risks.

Should You Soak Morel Mushrooms Before Cooking or Eating?

You may want to see also

Toxic vs. Edible Varieties

When exploring the safety of non-gill mushrooms, it’s crucial to distinguish between toxic and edible varieties, as misidentification can lead to severe health risks. Non-gill mushrooms, such as puffballs, coral fungi, and bracket fungi, lack the typical gill structure found in many common mushrooms. While some of these are safe and even prized for their culinary uses, others are highly toxic and can cause serious harm or even death if consumed. Understanding the key characteristics of toxic versus edible non-gill mushrooms is essential for foragers and enthusiasts.

Edible Non-Gill Mushrooms are often identified by their unique structures and lack of gills. For example, puffballs (genus *Calvatia* and *Lycoperdon*) are generally safe when young and white inside, but they must be cut open to ensure no gills or spores are present, as mature or impure specimens can be toxic. Coral mushrooms, such as *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower mushroom), are another edible group, known for their branching, coral-like appearance. These mushrooms are highly regarded for their flavor but require careful identification, as some coral species are toxic. Chanterelles, though they have false gills, are often included in non-gill discussions due to their distinct structure; they are edible and prized for their fruity aroma and golden color. Always ensure proper identification, as some toxic species, like the jack-o’-lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*), resemble chanterelles but have true gills and cause gastrointestinal distress.

Toxic Non-Gill Mushrooms pose significant risks and are often mistaken for their edible counterparts. For instance, false puffballs, such as the poisonous *Amanita ocreata* or *Amanita phalloides* in their early button stage, can resemble young puffballs but contain deadly amatoxins. Bracket fungi, while not typically consumed due to their woody texture, include both edible (e.g., *Laetiporus sulphureus*, chicken of the woods) and toxic species (e.g., *Hapalopilus rutilans*). Some coral fungi, like *Ramaria formosa*, are toxic and cause gastrointestinal symptoms despite their appealing appearance. Additionally, earthstars (genus *Geastrum*) are non-gill mushrooms that are generally considered inedible due to their tough texture and potential toxicity in some species.

To safely forage non-gill mushrooms, follow these guidelines: always cut specimens open to check for gills or unusual colors, consult reliable field guides or experts, and avoid consuming any mushroom unless 100% certain of its identity. Toxic mushrooms often lack obvious warning signs, making proper identification critical. For beginners, focus on easily identifiable edible species and avoid experimenting with unfamiliar varieties. Remember, while some non-gill mushrooms are culinary treasures, others can be dangerous or deadly.

In summary, the world of non-gill mushrooms offers both delights and dangers. Edible varieties like puffballs, chanterelles, and certain coral fungi are safe when properly identified, while toxic species such as false puffballs, poisonous brackets, and some corals can cause severe harm. Always prioritize caution, education, and verification to enjoy these fungi safely.

Are Wet Mushrooms Safe? Risks, Benefits, and Proper Handling Tips

You may want to see also

Common Safe Non-Gill Species

When exploring the safety of non-gill mushrooms, it’s essential to focus on species that are commonly recognized as safe for consumption. Non-gill mushrooms lack the typical gill structure found under the caps of many fungi and instead have unique features like pores, spines, or smooth undersides. Among these, several species are widely considered edible and are popular in culinary traditions worldwide. Below are some of the most common safe non-gill mushroom species that foragers and enthusiasts can confidently identify and consume.

One of the most well-known non-gill mushrooms is the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*). This distinctive mushroom has long, cascading spines instead of gills, resembling a lion’s mane. It is not only safe to eat but also highly prized for its seafood-like texture and flavor, often compared to crab or lobster. Lion’s Mane is commonly used in soups, stir-fries, and even as a meat substitute. Beyond its culinary appeal, it is also studied for its potential cognitive and neurological benefits, making it a dual-purpose mushroom for both the kitchen and health.

Another safe and popular non-gill species is the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). Named for its oyster-shell shape, this mushroom has a smooth, gill-less underside and grows in clusters on wood. Oyster mushrooms are widely cultivated and foraged due to their mild, savory flavor and versatile texture. They are excellent sautéed, grilled, or added to pasta dishes. Additionally, they are known for their ability to grow on a variety of substrates, making them a favorite among home cultivators. Their safety and accessibility have cemented their place in both gourmet and everyday cooking.

The Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) is another non-gill mushroom that is highly sought after by foragers. Instead of gills, it has a smooth to slightly wrinkled underside with forked ridges. Chanterelles are prized for their fruity aroma and chewy texture, which pairs well with eggs, creams, and sauces. They are commonly found in forests across North America, Europe, and Asia. Proper identification is crucial, as some toxic look-alikes exist, but true chanterelles are safe and a delicacy in many cuisines.

For those interested in unique textures, the Cauliflower Mushroom (*Sparassis crispa*) is a safe non-gill option. This mushroom resembles a head of cauliflower with its folded, branching structure. It has a meaty texture and absorbs flavors well, making it ideal for roasting or frying. Found at the base of hardwood trees, it is a seasonal treat in autumn. Its distinct appearance makes it easy to identify, and its safety is well-established among experienced foragers.

Lastly, the Puffball (*Calvatia gigantea*) is a safe and easily recognizable non-gill mushroom. Young puffballs have a smooth, white exterior and a solid, flesh-like interior without gills or spores. They are best when young and firm, with a flavor similar to tofu, making them a great canvas for seasonings. However, it’s crucial to avoid older puffballs, which release spores and become inedible. Proper identification is key, as some toxic mushrooms, like the Amanita species, can resemble puffballs in their early stages.

In summary, several non-gill mushrooms are safe and delicious, provided they are correctly identified. Lion’s Mane, Oyster Mushrooms, Chanterelles, Cauliflower Mushrooms, and Puffballs are excellent examples of common safe species that offer unique flavors and textures for culinary exploration. Always consult a field guide or expert when foraging, as misidentification can lead to serious consequences. With proper knowledge, these non-gill mushrooms can be a rewarding addition to any forager’s repertoire.

Delicious Enoki Mushrooms: Simple Tips for Cooking and Enjoying Them

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.99 $9.4

Symptoms of Poisoning Risks

Consuming non-gill mushrooms, such as those with pores, spines, or other structures instead of gills, carries significant poisoning risks if proper identification is not ensured. Symptoms of mushroom poisoning can vary widely depending on the species ingested, but they generally fall into several categories based on the toxins present. Gastrointestinal symptoms are among the most common and typically appear within 6 to 24 hours after consumption. These include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and cramps. Such symptoms often resemble food poisoning and can be mistaken for a stomach virus, making it crucial to consider recent mushroom consumption if these signs appear.

Neurological symptoms are another serious concern, particularly with toxic non-gill mushrooms like certain species of Amanita or false morels. These symptoms may manifest as confusion, dizziness, hallucinations, seizures, or even coma in severe cases. The onset can be rapid, sometimes occurring within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, depending on the toxin involved. For instance, amatoxins found in some Amanita species can cause severe liver and kidney damage, leading to life-threatening conditions if not treated promptly.

Cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms may also arise in cases of mushroom poisoning. These can include irregular heartbeat, low blood pressure, difficulty breathing, or even respiratory failure. Such symptoms often indicate a severe toxic reaction and require immediate medical attention. It is important to note that some toxic mushrooms, like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), can cause these symptoms without any initial gastrointestinal distress, making them particularly dangerous.

Delayed symptoms are a hallmark of certain poisonous non-gill mushrooms, such as those containing orellanine (found in some Cortinarius species) or cyclopeptides (found in some Amanita species). Orellanine poisoning, for example, may not show symptoms for 2 to 3 days after ingestion, leading to kidney failure if left untreated. Similarly, amatoxin poisoning can cause a "false recovery" phase, where symptoms seem to improve before rapidly worsening, often resulting in liver failure.

To mitigate these risks, immediate action is essential if poisoning is suspected. Contacting a poison control center, healthcare provider, or local mycological society can provide critical guidance. Bringing a sample of the mushroom or a detailed description can aid in identification and treatment. Prevention remains the best approach, emphasizing the importance of accurately identifying non-gill mushrooms before consumption and avoiding those with unknown safety profiles. When in doubt, it is always safer to discard the mushroom rather than risk poisoning.

Mushroom Discovery: Can This Fungus Really Consume Plastic Waste?

You may want to see also

Proper Preparation Methods

When preparing non-gill mushrooms for consumption, it’s crucial to start with proper identification. Many non-gill mushrooms, such as puffballs, chanterelles, and morels, are safe to eat, but misidentification can lead to poisoning. Always consult a reliable field guide or an experienced forager to confirm the species. Once you’re certain the mushroom is edible, the next step is to clean it thoroughly. Non-gill mushrooms often grow in soil and can harbor dirt, debris, and even insects. Gently brush off surface dirt with a soft brush or a damp cloth, avoiding excessive water, as mushrooms absorb moisture quickly and can become soggy.

After cleaning, the preparation method depends on the type of non-gill mushroom. For puffballs, for example, slice them open to ensure there are no gills or spores inside, as mature puffballs can be toxic. If the interior is solid white and firm, it’s safe to cook. Chanterelles and morels, on the other hand, require more thorough cleaning due to their ridged or honeycomb-like structures, which can trap dirt. Soak them briefly in cold water, then pat them dry with a paper towel or clean cloth. This step is essential to remove any hidden particles without compromising their texture.

Cooking non-gill mushrooms properly is vital to ensure safety and enhance flavor. Most non-gill mushrooms should be cooked thoroughly, as raw consumption can cause digestive discomfort or allergic reactions. Sautéing is a popular method, as it brings out their natural flavors. Heat a pan with butter or oil over medium heat, add the mushrooms, and cook until they are tender and lightly browned. For morels, a brief blanching in hot water before sautéing can help remove any remaining debris and reduce bitterness. Avoid eating non-gill mushrooms raw unless specifically advised for the species.

Some non-gill mushrooms, like chanterelles, pair well with creamy sauces or soups, while others, like puffballs, can be breaded and fried for a crispy texture. Regardless of the recipe, ensure the mushrooms are cooked until they reach an internal temperature of at least 165°F (74°C) to eliminate any potential toxins or harmful microorganisms. Proper cooking not only ensures safety but also improves digestibility and enhances the mushroom’s unique taste.

Finally, store non-gill mushrooms correctly if not using them immediately. Place them in a paper bag or wrap them loosely in a paper towel, then store them in the refrigerator. Avoid airtight containers or plastic bags, as these can trap moisture and cause the mushrooms to spoil quickly. Proper storage ensures they remain fresh and safe to eat for up to a week. By following these preparation methods, you can safely enjoy the diverse flavors and textures of non-gill mushrooms while minimizing risks.

Safely Enjoying Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide to Foraging and Cooking

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not all non-gill mushrooms are safe to eat. Some, like chanterelles and morels, are edible and highly prized, while others, such as the Amanita genus, are toxic and can be deadly. Always identify mushrooms accurately before consuming.

Identifying edible non-gill mushrooms requires knowledge of their specific characteristics, such as spore color, stem structure, and habitat. Consulting a field guide or a mycologist is essential, as relying on folklore or appearance alone can be dangerous.

Yes, many poisonous mushrooms lack gills, such as certain Amanita species and false morels. These can cause severe illness or death if ingested, so proper identification is crucial.

Most wild mushrooms, including non-gill varieties, should be cooked before eating to break down toxins and improve digestibility. Some species may still be toxic even when cooked, so always verify edibility first.