Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria, is often a subject of curiosity regarding its life cycle and reproductive mechanisms. While it undergoes complex stages of development, including asexual and sexual reproduction, it does not produce spores. Spores are typically associated with fungi, plants, and some bacteria as a means of dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. In contrast, Plasmodium relies on mosquito vectors for transmission and alternates between human and mosquito hosts to complete its life cycle. Understanding this distinction is crucial for accurately describing the parasite's biology and its role in causing malaria.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Is Plasmodium a spore? | No |

| Reason | Plasmodium is a genus of parasitic protozoans, not a fungus or plant that produces spores. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Plasmodium has a complex life cycle involving mosquitoes and vertebrate hosts, but it does not produce spores. Instead, it forms stages like sporozoites, merozoites, gametocytes, and ookinetes. |

| Reproductive Method | Asexual and sexual reproduction, but not through spore formation. |

| Classification | Protozoan (Kingdom: Protista, Phylum: Apicomplexa) |

| Common Misconception | Sometimes confused with fungal or plant spores due to the term "sporozoite," but sporozoites are not spores. |

| Disease Caused | Malaria, transmitted by infected mosquitoes. |

| Spore-like Stages | None; all stages are distinct and not classified as spores. |

What You'll Learn

- Plasmodium Life Cycle Stages: Does plasmodium produce spores during its complex life cycle

- Spore Definition vs. Plasmodium: Are plasmodium structures classified as spores biologically

- Reproduction Methods: How does plasmodium reproduce if not through spores

- Comparative Analysis: Do other parasites like plasmodium produce spores

- Scientific Classification: Is plasmodium categorized as a spore-forming organism in taxonomy

Plasmodium Life Cycle Stages: Does plasmodium produce spores during its complex life cycle?

Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria, undergoes a complex life cycle involving multiple stages and two hosts: humans and mosquitoes. A critical question arises: does this intricate process include the production of spores? To address this, let's dissect the life cycle and examine each stage for spore-like structures or functions.

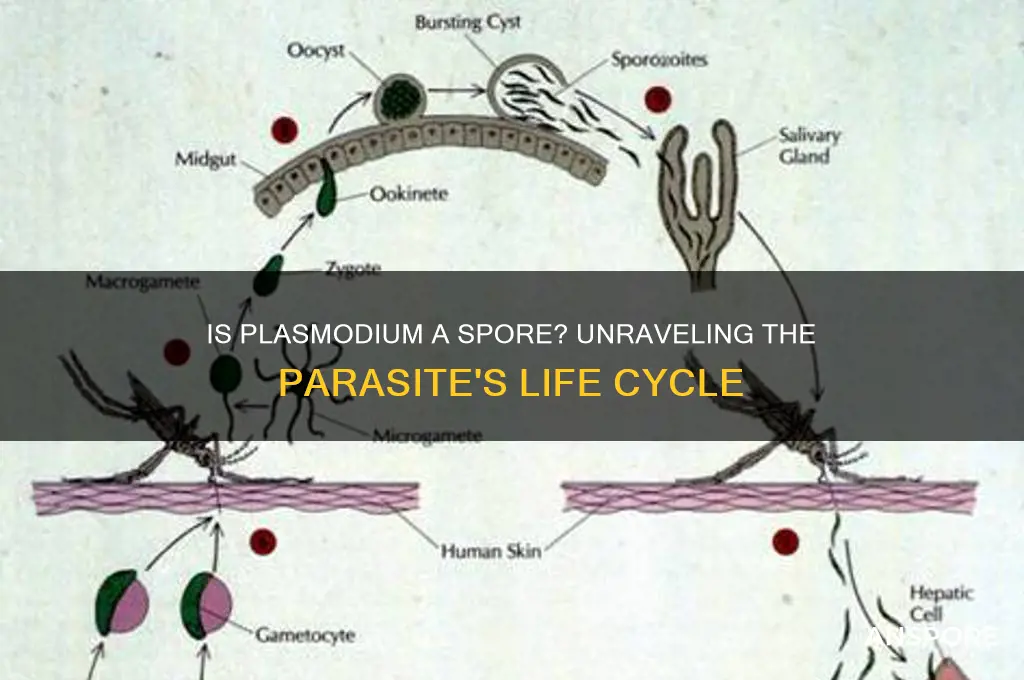

The Plasmodium Life Cycle: A Journey Through Stages

The life cycle begins when a female Anopheles mosquito, carrying the parasite, bites a human. Sporozoites, a motile and invasive form of the parasite, are injected into the bloodstream. These sporozoites quickly travel to the liver, where they invade hepatocytes and develop into schizonts. Within these liver cells, the parasites undergo asexual reproduction, resulting in the formation of merozoites. This liver stage is crucial, as it allows the parasite to multiply and prepare for the next phase.

After several days, the infected liver cells rupture, releasing merozoites into the bloodstream. These merozoites then invade red blood cells (RBCs), marking the beginning of the erythrocytic cycle. Inside the RBCs, the parasites develop into trophozoites, which feed on the cell's hemoglobin. As they mature, they become schizonts, undergoing another round of asexual reproduction to produce new merozoites. This cycle repeats, leading to the characteristic symptoms of malaria, including fever and anemia.

Analyzing Spore-like Characteristics

While the plasmodium life cycle is undoubtedly complex, it lacks a traditional spore-forming stage. Spores are typically associated with fungi and some bacteria, serving as resistant structures for survival and dispersal. In contrast, plasmodium's various forms (sporozoites, merozoites, trophozoites) are specialized for invasion, replication, and transmission, rather than long-term survival in harsh environments.

However, one could draw a comparative analogy between plasmodium's sporozoites and fungal spores. Both are dispersal forms, capable of surviving outside their immediate host environment. Sporozoites, when transmitted through mosquito saliva, can endure the journey from mosquito to human, similar to how fungal spores travel through air or water to reach new habitats. Yet, this comparison has limits; sporozoites are not dormant structures and lack the robust protective mechanisms of true spores.

In the context of its life cycle, plasmodium does not produce spores in the conventional sense. Its various stages are adapted for specific functions, such as invasion, replication, and transmission, rather than long-term survival. While sporozoites share some similarities with spores, they are not equivalent. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for developing targeted interventions, such as vaccines or drugs, that disrupt specific stages of the plasmodium life cycle, ultimately contributing to the global effort to eradicate malaria.

Bryophytes and Haploid Spores: Unraveling the Truth Behind Their Reproduction

You may want to see also

Spore Definition vs. Plasmodium: Are plasmodium structures classified as spores biologically?

Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria, undergoes complex life cycles involving multiple stages and hosts. One stage, the oocyst, forms on the midgut wall of a mosquito after it ingests infected blood. Within the oocyst, thousands of sporozoites develop, which are motile structures capable of migrating to the mosquito’s salivary glands. These sporozoites are often the focus when discussing whether plasmodium structures resemble spores. To determine if they fit the biological definition of spores, we must first examine what constitutes a spore.

Biologically, spores are reproductive or resistant structures produced by organisms such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria. They are typically unicellular, dormant, and capable of surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments trigger germination. Spores are also dispersal units, aiding in the spread of the species. In contrast, plasmodium sporozoites are not dormant; they remain metabolically active and do not serve as long-term survival structures. Instead, they are specialized for immediate transmission to a new host via the mosquito’s bite. This distinction challenges their classification as spores.

From a comparative perspective, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* or plant spores such as pollen are designed for endurance and dispersal. For example, fungal spores can survive extreme temperatures, desiccation, and UV radiation, often remaining viable for years. Plasmodium sporozoites, however, are fragile and short-lived outside their host environment. They rely on rapid transmission rather than long-term survival, which aligns more with the function of a transient infective stage than a true spore.

Persuasively, classifying plasmodium sporozoites as spores could lead to confusion in biological terminology. While they share some superficial similarities, such as being unicellular and involved in dispersal, their functional roles differ significantly. Spores are primarily reproductive and resistant, whereas sporozoites are infective agents optimized for immediate host invasion. Adhering to precise definitions ensures clarity in scientific communication and avoids misclassification of distinct biological structures.

In conclusion, while plasmodium sporozoites share certain characteristics with spores, they do not meet the biological criteria for classification as such. Their active metabolism, lack of dormancy, and specialized role in infection distinguish them from true spores. Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate scientific discourse and for appreciating the unique adaptations of plasmodium in its life cycle.

Mastering Spore Prints: A Step-by-Step Guide Using Spore Syringes

You may want to see also

Reproduction Methods: How does plasmodium reproduce if not through spores?

Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria, does not reproduce through spores. Instead, it employs a complex life cycle involving both asexual and sexual reproduction phases, each occurring in different hosts—mosquitoes and humans. Understanding these methods is crucial for developing targeted interventions against malaria.

Asexual Reproduction: The Human Phase

In humans, Plasmodium reproduces asexually through a process called schizogony. After a mosquito bite introduces the parasite into the bloodstream, it travels to the liver, where it infects hepatocytes. Within these cells, a single parasite undergoes multiple rounds of division, producing thousands of merozoites. These merozoites burst from the liver cell, re-enter the bloodstream, and invade red blood cells (RBCs). Inside RBCs, each merozoite grows into a trophozoite, which then divides into 16–32 new merozoites. This cycle repeats, causing the periodic fever and chills characteristic of malaria. For instance, *Plasmodium falciparum* completes this cycle every 48 hours, while *P. vivax* takes 72 hours. This rapid replication leads to the destruction of RBCs and the release of toxins, contributing to disease symptoms.

Sexual Reproduction: The Mosquito Phase

Sexual reproduction occurs in the mosquito vector, a critical step for the parasite’s survival and transmission. When a mosquito feeds on an infected human, it ingests male and female gametocytes—specialized sexual forms of the parasite. Within the mosquito’s gut, these gametocytes mature and fuse to form a zygote, which develops into an ookinete. The ookinete penetrates the mosquito’s midgut wall and forms an oocyst. Inside the oocyst, the parasite undergoes another round of asexual replication, producing thousands of sporozoites. These sporozoites migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands, ready to be transmitted to the next human host during a bite. This phase ensures genetic diversity through recombination, enhancing the parasite’s adaptability.

Key Takeaways for Prevention and Treatment

Targeting these reproduction methods is essential for malaria control. Antimalarial drugs like chloroquine and artemisinin disrupt asexual replication in RBCs, while primaquine targets liver-stage parasites and gametocytes. Mosquito control measures, such as insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying, reduce transmission by limiting the sexual phase. Understanding these distinct reproductive strategies highlights the need for multifaceted approaches to combat malaria effectively. For travelers to endemic regions, prophylactic medications like atovaquone-proguanil (250 mg/100 mg daily) can prevent infection by inhibiting both liver and blood stages.

Comparative Insight: Spores vs. Plasmodium’s Methods

Unlike spore-forming organisms, which produce dormant, resilient structures for survival, Plasmodium relies on continuous replication and host switching. Spores are typically associated with fungi and some bacteria, serving as a means of dispersal and endurance in harsh conditions. In contrast, Plasmodium’s life cycle is tightly coupled with its hosts, requiring specific environmental and physiological conditions for each phase. This dependency makes it vulnerable to interventions but also challenging to eradicate due to its complexity and adaptability. By focusing on disrupting its unique reproductive mechanisms, researchers can develop more effective strategies against this deadly parasite.

Mastering Spore Galactic Adventures: Creative Tips to Enlarge Objects Effortlessly

You may want to see also

Comparative Analysis: Do other parasites like plasmodium produce spores?

Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria, does not produce spores. Instead, it undergoes complex life cycle stages involving mosquitoes and humans, alternating between asexual replication (schizogony) and sexual reproduction (sporogony). This raises the question: do other parasites employ spore-like mechanisms for survival and transmission? A comparative analysis reveals diverse strategies among parasitic organisms, some of which resemble spore production in function, if not in form.

Consider *Toxoplasma gondii*, a protozoan parasite causing toxoplasmosis. While it does not produce spores, it forms environmentally resistant oocysts in the intestines of its definitive host (felines). These oocysts, akin to spores in their durability, can survive in soil for months, facilitating transmission to intermediate hosts like humans. Similarly, *Cryptosporidium*, a waterborne parasite, produces oocysts that withstand harsh conditions, enabling its spread through contaminated water sources. These examples highlight how certain parasites develop spore-like structures to ensure persistence outside hosts, a strategy absent in Plasmodium.

In contrast, helminths (parasitic worms) like *Schistosoma* and *Taenia* rely on eggs or cysts for transmission, which, while not spores, serve comparable ecological roles. For instance, *Schistosoma* eggs are excreted in urine or feces and hatch upon contact with freshwater, releasing miracidia that infect intermediate snail hosts. This protective encapsulation mirrors the function of spores, ensuring survival during vulnerable life stages. However, these structures lack the dormant, highly resistant characteristics typically associated with true spores found in fungi or bacteria.

A key takeaway is that while spore production is not a universal trait among parasites, many have evolved analogous mechanisms to enhance survival and transmission. These adaptations—whether oocysts, eggs, or cysts—underscore the convergent evolution of protective strategies in parasitic life cycles. Unlike Plasmodium, which relies on rapid replication and vector-mediated transmission, these parasites prioritize environmental resilience, trading immediate proliferation for long-term persistence.

Practically, understanding these differences informs targeted interventions. For instance, disrupting oocyst or egg viability through environmental sanitation or chemical treatments could curb transmission of *Toxoplasma* or *Schistosoma*, whereas Plasmodium control focuses on vector management and drug therapy. This comparative analysis not only clarifies the absence of spores in Plasmodium but also illuminates the diverse survival strategies of parasitic organisms, offering insights for disease prevention and treatment.

Can Steam Mops Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

Scientific Classification: Is plasmodium categorized as a spore-forming organism in taxonomy?

Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria, is a complex organism with a life cycle spanning multiple hosts and stages. In scientific classification, it belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa and the genus Plasmodium. However, when considering whether Plasmodium is categorized as a spore-forming organism in taxonomy, it’s essential to clarify the distinction between spores and the reproductive stages of this parasite. Spores are typically associated with fungi, plants, and some bacteria, serving as dormant, resilient structures for survival and dispersal. Plasmodium, in contrast, does not produce spores. Instead, it undergoes asexual and sexual reproduction through stages like merozoites, gametocytes, and ookinetes, none of which are taxonomically classified as spores.

To understand why Plasmodium is not considered spore-forming, examine its life cycle. In the mosquito vector, the parasite develops into oocysts, which release sporozoites—infective forms that migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands. While "sporozoite" contains the root "spore," this term is a misnomer in the context of spore-forming organisms. Sporozoites are motile, invasive cells, not dormant survival structures. Similarly, in the human host, Plasmodium produces merozoites during the asexual blood stage, but these are replicative forms, not spores. Taxonomy does not classify any of these stages as spores, as they lack the defining characteristics of true spores, such as dormancy and resistance to harsh conditions.

From a taxonomic perspective, the classification of Plasmodium as a non-spore-forming organism is rooted in its evolutionary lineage and reproductive strategies. Apicomplexans, the group to which Plasmodium belongs, are primarily intracellular parasites that rely on complex life cycles for transmission. Their reproductive stages are adapted for invasion and replication, not for long-term survival outside a host. In contrast, spore-forming organisms like fungi and certain bacteria produce spores as a survival mechanism, often in response to environmental stress. Plasmodium’s life cycle lacks this adaptive feature, reinforcing its taxonomic distinction from spore-forming taxa.

Practically, this classification has implications for malaria control and research. Understanding that Plasmodium does not form spores helps focus efforts on targeting its vulnerable life stages, such as sporozoites during transmission or merozoites during blood infection. For instance, vaccines like RTS,S aim to block sporozoite invasion of the liver, while antimalarial drugs like chloroquine target blood-stage merozoites. Recognizing the parasite’s non-spore-forming nature ensures that interventions are tailored to its actual biology, avoiding misdirected strategies based on incorrect taxonomic assumptions.

In conclusion, Plasmodium is not categorized as a spore-forming organism in taxonomy. Its reproductive stages, though diverse and complex, do not align with the characteristics of spores. This distinction is critical for both scientific accuracy and practical applications in combating malaria. By focusing on Plasmodium’s unique biology, researchers and healthcare providers can develop more effective strategies to control this devastating parasite.

Buying Psychedelic Mushroom Spores: Legal or Illegal? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Plasmodium is not a spore. It is a parasitic protozoan that causes malaria in humans and other animals.

Plasmodium has a complex life cycle involving both mosquitoes and vertebrate hosts. It does not produce spores; instead, it undergoes stages like sporozoites, merozoites, and gametocytes.

No, Plasmodium does not produce spores at any stage of its life cycle. Spores are typically associated with fungi and some bacteria, not protozoa like Plasmodium.

Plasmodium reproduces both asexually (through binary fission in the liver and red blood cells) and sexually (in the mosquito gut, forming zygotes and ookinetes).

While Plasmodium and spore-forming organisms both have complex life cycles, they are distinct. Plasmodium is a protozoan parasite, whereas spore-forming organisms are typically fungi, bacteria, or plants.