Pollen and spores are often confused due to their microscopic size and role in plant reproduction, but they serve distinct purposes and originate from different types of organisms. Pollen is produced by seed-bearing plants, such as flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (gymnosperms), and functions as the male gametophyte in sexual reproduction, transferring genetic material to the female reproductive structures. In contrast, spores are produced by non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, as well as by some bacteria and algae, and are typically involved in asexual reproduction or dispersal, allowing these organisms to survive harsh conditions and colonize new environments. While both are essential for the life cycles of their respective organisms, their structures, functions, and evolutionary origins highlight key differences between these two reproductive units.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Pollen: Fine powdery particles produced by flowering plants for reproduction. Spores: Reproductive units produced by plants (like ferns, mosses), fungi, and some bacteria. |

| Producers | Pollen: Produced by angiosperms (flowering plants) and gymnosperms (e.g., conifers). Spores: Produced by non-flowering plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), fungi, and some bacteria. |

| Function | Pollen: Primarily for sexual reproduction via pollination. Spores: Primarily for asexual reproduction or dispersal in adverse conditions. |

| Structure | Pollen: Contains male gametes (sperm cells) and is often larger and more complex. Spores: Typically single-celled and simpler in structure. |

| Dispersal | Pollen: Dispersed by wind, water, or animals (e.g., insects). Spores: Dispersed by wind, water, or other environmental factors. |

| Size | Pollen: Generally larger (10–200 micrometers). Spores: Generally smaller (1–50 micrometers). |

| Allergenicity | Pollen: Common allergen for many people (e.g., hay fever). Spores: Some fungal spores can cause allergies but are less commonly associated with seasonal allergies. |

| Lifespan | Pollen: Short-lived, typically viable for a few days to weeks. Spores: Can remain dormant for extended periods (years to decades) under favorable conditions. |

| Environmental Role | Pollen: Key in plant reproduction and ecosystem health. Spores: Important in decomposition, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience. |

What You'll Learn

Pollen vs Spores: Reproduction Methods

Pollen and spores are both reproductive units, but they serve distinct purposes and operate through fundamentally different mechanisms. Pollen is produced by seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) and functions exclusively in sexual reproduction. It contains the male gametes necessary for fertilizing the female ovule, ultimately leading to seed formation. Spores, on the other hand, are produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, as well as some algae and bacteria. Unlike pollen, spores are typically unicellular and can reproduce both sexually and asexually, often developing into new organisms without fertilization.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern to illustrate the spore’s versatility. Ferns release spores that germinate into small, heart-shaped structures called prothalli. These prothalli produce both male and female reproductive cells, which require water to swim and unite, forming a new fern plant. This process, known as alternation of generations, highlights the spore’s role in both sexual and asexual reproduction. Pollen, in contrast, is part of a more direct reproductive cycle. For example, in flowering plants, pollen grains land on the stigma of a flower, grow down the style, and fertilize the ovule, a process dependent on external agents like wind, water, or animals for pollination.

The structural differences between pollen and spores further underscore their distinct roles. Pollen grains are often larger and more complex, with protective outer layers (exine and intine) that aid in survival during transport. Some pollen grains even have spines or grooves to attach to pollinators. Spores, however, are typically smaller and simpler, designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. For instance, fungal spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate. This adaptability makes spores ideal for colonizing new environments, while pollen’s specialized structure reflects its singular focus on fertilization.

Practical implications of these differences are evident in agriculture and medicine. Farmers and gardeners must understand pollen’s role in plant breeding to optimize crop yields. For example, hand-pollination in greenhouses ensures consistent fruit production in the absence of natural pollinators. Spores, meanwhile, are critical in the spread of diseases like athlete’s foot (caused by fungal spores) and in the production of antibiotics like penicillin, derived from fungal spore cultures. Recognizing these distinctions allows for targeted interventions, whether enhancing pollination or controlling spore-borne pathogens.

In summary, while both pollen and spores are reproductive units, their methods and purposes diverge sharply. Pollen is a specialized agent of sexual reproduction in seed plants, reliant on external vectors for success. Spores, with their dual reproductive capabilities and resilient structure, are the lifeblood of non-seed plants and fungi, enabling survival and dispersal in diverse environments. Understanding these differences not only clarifies their biological roles but also informs practical applications in agriculture, medicine, and conservation.

Cordyceps Spore Spread: How This Fungus Infects and Propagates

You may want to see also

Structural Differences: Pollen vs Spores

Pollen and spores, though both reproductive units, exhibit distinct structural differences that reflect their unique biological roles. Pollen grains, produced by seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms), are typically larger and more complex, ranging from 10 to 100 micrometers in diameter. They are encased in a robust, multilayered wall composed of an outer exine and inner intine. The exine is often sculptured with intricate patterns (e.g., spines, ridges) that aid in dispersal and adhesion to pollinators. In contrast, spores, produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, are generally smaller, measuring 5 to 50 micrometers. Their walls are simpler, usually consisting of a single layer of sporopollenin, a durable polymer that protects the spore during dormancy and dispersal.

Consider the functional implications of these structural differences. Pollen’s larger size and complex wall structure are adaptations for animal-mediated pollination, ensuring successful transfer between flowers. For instance, the spiny surface of sunflower pollen helps it adhere to bee bodies. Spores, however, are designed for wind or water dispersal and long-term survival in harsh conditions. Fern spores, for example, can remain dormant for years, their smooth, lightweight structure allowing them to travel vast distances. This contrast highlights how form follows function in reproductive biology.

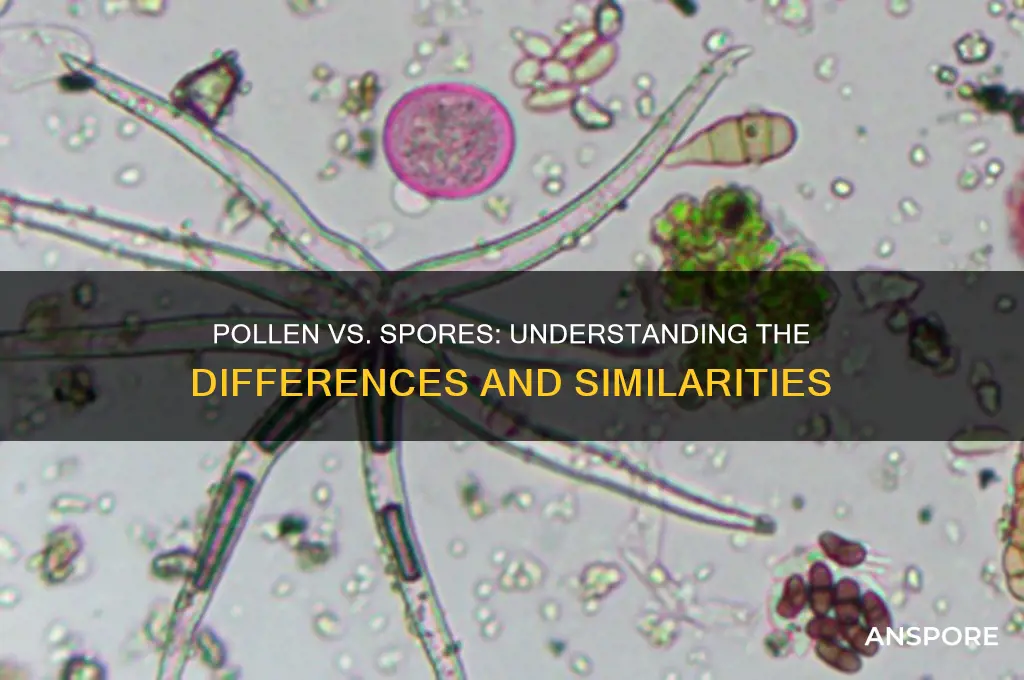

To illustrate these differences practically, examine pollen and spores under a microscope. Pollen grains often appear brightly colored (yellow, orange) due to pigments like carotenoids, which attract pollinators. Spores, in contrast, are typically colorless or pale, reflecting their reliance on passive dispersal. For educators or hobbyists, preparing a slide of pine pollen (gymnosperm) and fern spores side by side can demonstrate these variations. Use a 40x objective lens to observe the pollen’s sculptured exine and the spore’s smooth, uniform wall. This hands-on approach reinforces the structural distinctions between the two.

From an evolutionary perspective, these differences underscore divergent reproductive strategies. Pollen’s complexity evolved alongside animal pollinators, a co-adaptation that enhances fertilization efficiency. Spores, however, represent an older strategy, predating seed plants by millions of years. Their simplicity and durability reflect a reliance on environmental factors for dispersal and germination. Understanding these structural differences not only clarifies their roles but also highlights the diversity of plant reproductive mechanisms.

In practical applications, such as allergy management, these structural differences are crucial. Pollen’s larger size (20–70 micrometers) makes it a common allergen, as it can irritate nasal passages but rarely reaches the lungs. Spores, being smaller (5–50 micrometers), can penetrate deeper into the respiratory system, potentially causing more severe reactions in sensitive individuals. For allergy sufferers, monitoring pollen counts (e.g., using apps like Pollen.com) and wearing masks during high-spore seasons (e.g., fall for mold spores) can mitigate symptoms. This knowledge bridges the gap between biology and everyday health.

Mastering Psilocybe Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Spores

You may want to see also

Plants vs Fungi: Producers of Each

Pollen and spores, though both microscopic reproductive units, serve distinct purposes in the life cycles of plants and fungi, respectively. This distinction highlights the fundamental differences in how these two kingdoms propagate and survive. Plants, as primary producers, rely on pollen to facilitate sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptation. Fungi, on the other hand, produce spores as a means of asexual reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions. Understanding these differences is crucial for appreciating the unique ecological roles of plants and fungi.

Analytical Perspective:

Plants produce pollen as part of their flowering process, a mechanism tightly linked to their role as producers in ecosystems. Pollen grains contain male gametes and are transferred between flowers, often via pollinators like bees, to fertilize female ovules. This process is energy-intensive but ensures genetic recombination, which is vital for plant evolution. Fungi, in contrast, produce spores as a low-energy, high-volume strategy. Spores are lightweight, resilient, and can remain dormant for years, allowing fungi to colonize new environments rapidly. While plants invest in quality (pollen), fungi prioritize quantity (spores), reflecting their distinct ecological strategies.

Instructive Approach:

To differentiate between pollen and spores in practical terms, consider their structure and function. Pollen grains are typically larger (20–70 micrometers) and contain nutrients to support germination upon reaching the stigma. They are often sticky or spiky to adhere to pollinators. Spores, however, are smaller (1–10 micrometers) and designed for dispersal, with features like wings or hydrophobic surfaces. For example, if you’re examining a sample under a microscope, look for these characteristics: pollen will appear granular and varied in shape, while spores will be more uniform and streamlined. This distinction is essential for botanists, mycologists, and even allergy sufferers, as pollen is a common allergen, while spores are less so.

Comparative Analysis:

The production of pollen and spores also reflects the contrasting lifestyles of plants and fungi. Plants are sessile organisms that invest heavily in structural growth (roots, stems, leaves) and reproductive precision. Pollen production is part of this strategy, ensuring successful fertilization despite limited mobility. Fungi, however, are decomposers and saprotrophs, thriving in nutrient-poor environments. Spores allow them to disperse widely and colonize new substrates efficiently. For instance, a single mushroom can release billions of spores in a day, while a flower produces a limited number of pollen grains. This comparison underscores how each organism’s reproductive strategy aligns with its ecological niche.

Descriptive Insight:

Imagine a forest ecosystem: plants dominate the canopy, their flowers releasing pollen into the air, carried by the wind or insects to distant mates. Below, fungi decompose fallen leaves and wood, their mycelial networks hidden beneath the soil. When conditions are right, fungi produce fruiting bodies like mushrooms, which release spores into the air. These spores drift on currents, landing on new substrates to start the cycle anew. While pollen is a fleeting, seasonal phenomenon tied to plant reproduction, spores are a year-round, ubiquitous presence, ensuring fungal survival across seasons and environments. This interplay between pollen and spores highlights the complementary roles of plants and fungi in sustaining ecosystems.

Persuasive Argument:

Understanding the differences between pollen and spores is not just academic—it has practical implications for agriculture, medicine, and conservation. Farmers rely on pollen for crop fertilization, while mycologists harness spores for fungal cultivation and bioremediation. Allergy sufferers need to distinguish between pollen (a common trigger) and spores (less allergenic). By recognizing these distinctions, we can better manage ecosystems, improve agricultural practices, and address health concerns. For instance, planting wind-pollinated crops away from residential areas can reduce pollen exposure, while using fungal spores in soil restoration can enhance nutrient cycling. This knowledge empowers us to work with nature, not against it.

Effortless Spore Registration: A Step-by-Step Guide Without the Manual

You may want to see also

Allergies: Pollen vs Spores Impact

Pollen and spores, though both microscopic particles dispersed by plants, serve distinct biological purposes and trigger different allergic responses. Pollen, produced by flowering plants, is essential for plant reproduction and is often carried by wind or insects. Spores, on the other hand, are reproductive units of fungi, molds, and non-flowering plants like ferns, designed to survive harsh conditions and disperse widely. While both can cause allergies, their sources, seasons, and symptoms vary significantly.

For allergy sufferers, understanding the difference between pollen and spores is crucial for effective management. Pollen allergies, commonly known as hay fever, peak during specific seasons—spring for tree pollen, summer for grass pollen, and fall for weed pollen. Symptoms include sneezing, runny nose, and itchy eyes. Spores, particularly mold spores, thrive in damp environments and can cause year-round allergies, especially indoors. Mold spore allergies often manifest as respiratory issues, such as coughing, wheezing, and asthma exacerbations. Monitoring local pollen and mold counts can help individuals anticipate and mitigate exposure.

Practical steps to reduce pollen and spore exposure differ due to their unique characteristics. For pollen allergies, keep windows closed during high-count days, use air purifiers with HEPA filters, and shower before bed to remove particles from hair and skin. For spore allergies, focus on moisture control: fix leaks, use dehumidifiers to keep indoor humidity below 50%, and clean mold-prone areas like bathrooms and basements regularly. Additionally, wearing masks during outdoor activities in high-spore environments can provide extra protection.

Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to both pollen and spore allergies due to developing or weakened immune systems. For children, limit outdoor play during peak pollen hours (typically mid-morning and early evening) and ensure schools are aware of their allergies. For older adults, regular home maintenance to prevent mold growth and consistent use of prescribed allergy medications are essential. Both groups may benefit from allergy testing to identify specific triggers and tailor treatment plans.

In conclusion, while pollen and spores share similarities as airborne allergens, their origins, seasons, and management strategies differ. Pollen allergies are seasonal and tied to outdoor exposure, while spore allergies persist year-round and are often linked to indoor environments. By recognizing these distinctions and implementing targeted measures, individuals can effectively reduce their allergy symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Mildew Spores and Kidney Health: Uncovering Potential Risks and Impacts

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: How They Spread Differently

Pollen and spores, though both reproductive units, employ distinct dispersal mechanisms tailored to their biological roles. Pollen, produced by seed plants, relies heavily on external agents like wind, water, and animals for transport. Wind-pollinated plants, such as grasses and pines, release lightweight, dry pollen grains in vast quantities to increase the likelihood of reaching a receptive stigma. Animal-pollinated plants, like flowers, produce sticky, protein-rich pollen carried by insects or birds, often in exchange for nectar. In contrast, spores, produced by fungi, ferns, and mosses, are designed for survival and dispersal in diverse environments. Fungal spores, for instance, may be ejected forcibly from structures like sporangia, while fern spores are often dispersed by wind due to their minute size and lightweight nature.

Consider the anatomical adaptations that facilitate these dispersal strategies. Pollen grains are typically larger and more robust, equipped with structures like spines or grooves to aid in attachment to pollinators. Spores, however, are smaller and more numerous, often with thick cell walls to withstand harsh conditions. For example, fungal spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This difference in design reflects their respective functions: pollen seeks immediate fertilization, while spores prioritize long-term survival and colonization of new habitats.

To illustrate, compare the dispersal of ragweed pollen and fern spores. Ragweed, a wind-pollinated plant, releases billions of pollen grains annually, each capable of traveling miles in the air. This efficiency comes at a cost: it’s a leading cause of seasonal allergies, affecting up to 23 million Americans. Fern spores, on the other hand, are dispersed in smaller quantities but are adapted to survive extreme conditions, such as desiccation or freezing temperatures. A single fern sporophyte can release thousands of spores, ensuring at least a few land in suitable environments for growth.

Practical implications arise from understanding these mechanisms. For allergy sufferers, monitoring pollen forecasts and staying indoors during peak wind-pollination times (typically early morning) can reduce exposure. Gardeners can exploit spore dispersal by creating moist, shaded environments to encourage fern growth. Farmers of wind-pollinated crops like corn can optimize planting patterns to maximize pollen overlap between fields. Conversely, understanding spore dispersal helps in controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture; for instance, reducing humidity can inhibit spore germination in crops like wheat.

In conclusion, while pollen and spores share a reproductive purpose, their dispersal mechanisms are finely tuned to their ecological niches. Pollen’s reliance on external vectors contrasts with spores’ self-sufficient, resilient design. By studying these differences, we gain insights into plant and fungal biology, as well as practical strategies for managing allergies, agriculture, and ecosystems. Whether you’re a gardener, farmer, or allergy sufferer, understanding these mechanisms empowers you to work with, rather than against, nature’s design.

Effective Methods to Destroy Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, pollen and spores are not the same thing. Pollen is produced by seed-bearing plants (like flowers) for reproduction, while spores are produced by non-seed plants (like ferns and fungi) for reproduction and dispersal.

Both pollen and spores are involved in reproduction, but they serve different purposes. Pollen is specifically for fertilizing seeds in flowering plants, whereas spores are used for asexual reproduction and can develop into new organisms under the right conditions.

Pollen is a common allergen for many people, causing symptoms like sneezing and itching. Spores, particularly from molds and fungi, can also trigger allergies, but they are less frequently associated with seasonal allergies compared to pollen.

Pollen is most commonly found in environments with flowering plants, such as gardens, fields, and forests. Spores are more prevalent in damp, humid environments where fungi and non-seed plants thrive, like basements, soil, and decaying organic matter.