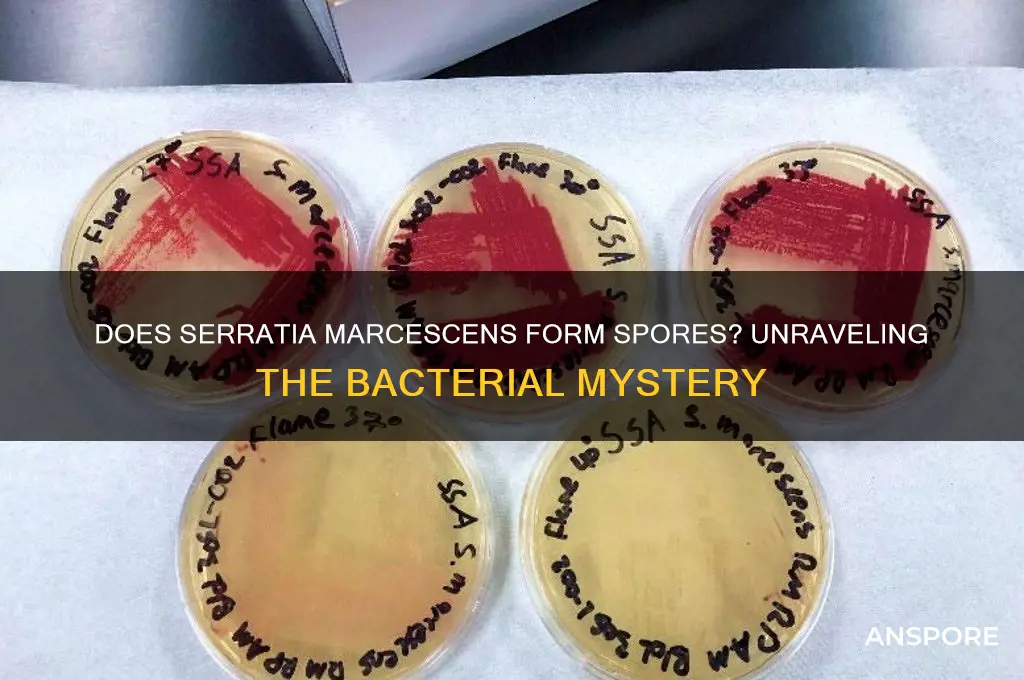

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium known for its distinctive red pigmentation, is often a topic of interest in microbiology due to its environmental prevalence and potential pathogenicity. One common question surrounding this bacterium is whether it is spore-forming, a characteristic that would significantly impact its survival and transmission. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus or Clostridium, Serratia marcescens does not produce spores. Instead, it relies on its robust survival mechanisms, including biofilm formation and resistance to desiccation, to persist in various environments. Understanding its non-spore-forming nature is crucial for effective infection control and treatment strategies, as it influences how the bacterium spreads and responds to disinfection methods.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | No, Serratia marcescens is a non-spore-forming bacterium. |

| Gram Staining | Gram-negative |

| Morphology | Rod-shaped (bacilli) |

| Motility | Motile (possesses peritrichous flagella) |

| Colony Appearance | Red pigmented colonies due to production of prodigiosin |

| Optimal Growth Temperature | 30-37°C (mesophilic) |

| Oxygen Requirement | Facultative anaerobe |

| Habitat | Soil, water, and gastrointestinal tracts of animals and humans |

| Pathogenicity | Opportunistic pathogen, can cause infections in immunocompromised hosts |

| Antibiotic Resistance | Increasing resistance to multiple antibiotics |

| Biochemical Tests | Positive for catalase, oxidase, and citrate utilization |

| Clinical Significance | Associated with hospital-acquired infections (e.g., UTIs, pneumonia) |

| Identification | Identified by biochemical tests and molecular methods (e.g., 16S rRNA sequencing) |

What You'll Learn

Serratia Marcescens Spore Formation Mechanism

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium known for its vibrant red pigmentation, has long intrigued microbiologists due to its adaptability and resilience. One question that frequently arises is whether this bacterium forms spores, a survival mechanism common in other species like Bacillus and Clostridium. Research indicates that Serratia marcescens is not a spore-forming bacterium. Unlike spore-formers, which produce highly resistant endospores to withstand harsh conditions, S. marcescens relies on other strategies for survival, such as biofilm formation and metabolic flexibility. This distinction is critical in clinical and industrial settings, where understanding its survival mechanisms informs disinfection protocols and infection control measures.

To explore the absence of spore formation in S. marcescens, it’s essential to examine its cellular mechanisms. Spore formation typically involves a complex process of asymmetric cell division, culminating in the creation of a durable spore coat. S. marcescens lacks the genetic machinery required for this process, specifically the *spo* genes found in spore-forming bacteria. Instead, it employs alternative strategies, such as producing extracellular polysaccharides to form biofilms, which protect it from environmental stressors like desiccation and antimicrobials. This biofilm matrix acts as a surrogate defense mechanism, compensating for the absence of spores.

From a practical standpoint, the non-spore-forming nature of S. marcescens has significant implications for disinfection practices. Since spores are notoriously resistant to common disinfectants like alcohol and quaternary ammonium compounds, non-spore-forming bacteria like S. marcescens are generally easier to eradicate. However, its biofilm-forming ability poses a unique challenge, particularly in healthcare settings. To effectively eliminate S. marcescens, use disinfectants with broad-spectrum activity, such as chlorine-based solutions or hydrogen peroxide, and ensure thorough surface cleaning to disrupt biofilms. Regular monitoring of high-risk areas, such as hospital sinks and respiratory equipment, is also crucial.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation in S. marcescens highlights its evolutionary trade-offs. While spore-forming bacteria can survive extreme conditions for years, S. marcescens thrives in nutrient-rich environments, such as water systems and medical devices. Its ability to rapidly adapt to new niches, coupled with its biofilm formation, allows it to persist in healthcare settings despite its lack of spores. This adaptability underscores the importance of targeted infection control strategies, focusing on environmental hygiene and early detection of outbreaks.

In conclusion, while Serratia marcescens does not form spores, its survival mechanisms are no less formidable. Understanding its reliance on biofilms and metabolic versatility provides actionable insights for preventing and managing infections. By tailoring disinfection protocols to its unique characteristics, healthcare professionals and researchers can mitigate the risks posed by this resilient bacterium.

Mastering Planet Spore: Exclusive Creations for Your Unique World

You may want to see also

Environmental Conditions for Spore Production

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is known for its vibrant red pigmentation and opportunistic pathogenic nature. Despite its resilience and ability to thrive in diverse environments, Serratia marcescens is not a spore-forming bacterium. Unlike spore-formers such as Bacillus or Clostridium, it lacks the genetic machinery to produce endospores, which are highly resistant structures enabling survival in harsh conditions. However, understanding the environmental conditions that might influence its survival and proliferation is crucial, as these factors can mimic the protective effects of spore formation in other species.

To explore the environmental conditions that could enhance Serratia marcescens' survival, consider factors such as nutrient availability, pH levels, temperature, and moisture content. For instance, this bacterium thrives in moist environments with temperatures ranging from 20°C to 37°C, with optimal growth at 30°C to 35°C. In healthcare settings, it often colonizes areas with high humidity, such as respiratory equipment or shower facilities. While these conditions do not induce spore formation, they create an ideal milieu for its persistence and dissemination. Practical tips include maintaining relative humidity below 50% in clinical environments and regularly disinfecting surfaces with quaternary ammonium compounds or 70% ethanol to inhibit its growth.

Analyzing the role of nutrient availability reveals that Serratia marcescens can adapt to low-nutrient environments, a trait often associated with spore-formers. It can utilize a variety of carbon sources, including amino acids and sugars, allowing it to survive in nutrient-poor settings like soil or water systems. However, unlike spores, which remain dormant until conditions improve, Serratia marcescens remains metabolically active, albeit at a reduced rate. This distinction highlights the importance of proactive environmental management: limiting nutrient sources in at-risk areas, such as removing organic debris from water reservoirs or using closed systems in healthcare devices, can significantly reduce its proliferation.

A comparative analysis with spore-forming bacteria underscores the limitations of Serratia marcescens in extreme conditions. While spores can withstand temperatures above 100°C, desiccation, and exposure to UV radiation, Serratia marcescens is far more susceptible to these stressors. For example, it is effectively inactivated by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, a standard sterilization method that targets vegetative cells. However, its ability to form biofilms—a protective matrix of extracellular polymeric substances—partially compensates for its lack of spores. Biofilms enhance its resistance to antimicrobials and environmental stresses, making them a critical target for control strategies. Regular mechanical disruption of biofilms, combined with chemical disinfection, is essential in high-risk settings.

In conclusion, while Serratia marcescens does not produce spores, its survival in diverse environments is facilitated by specific conditions that mimic the protective effects of spore formation. By focusing on controlling temperature, humidity, nutrient availability, and biofilm formation, one can effectively mitigate its persistence. This knowledge is particularly valuable in healthcare and industrial settings, where preventing contamination is paramount. Understanding these environmental conditions not only highlights the bacterium's vulnerabilities but also informs targeted interventions to curb its spread.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores from Your Carpet Safely

You may want to see also

Spore Formation vs. Vegetative Growth

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is known for its striking red pigmentation and environmental resilience. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, *S. marcescens* does not produce spores. Instead, it relies solely on vegetative growth for survival and proliferation. This distinction is critical in understanding its behavior in clinical and environmental settings, as spore formation confers extreme durability, while vegetative growth is more susceptible to environmental stressors.

Vegetative growth in *S. marcescens* occurs through binary fission, a rapid process under optimal conditions (25–37°C, nutrient-rich media). This phase allows the bacterium to colonize diverse habitats, from soil and water to medical devices and human tissues. However, without spore formation, *S. marcescens* is vulnerable to desiccation, UV radiation, and disinfectants. For instance, a 10-minute exposure to 70% ethanol can effectively kill vegetative cells, whereas spores of *Bacillus* species may survive hours under the same conditions. This vulnerability limits its long-term survival in harsh environments but also makes it more manageable in infection control.

In contrast, spore-forming bacteria enter a dormant state characterized by minimal metabolic activity and a robust, multilayered spore coat. Spores can withstand extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and chemicals, for years or even decades. For example, *Clostridium difficile* spores can persist on hospital surfaces for up to 5 months, contributing to healthcare-associated infections. The absence of spore formation in *S. marcescens* means it lacks this survival mechanism, making it less likely to cause outbreaks via environmental reservoirs.

Clinically, the vegetative nature of *S. marcescens* has implications for treatment and prevention. Antibiotics targeting cell wall synthesis (e.g., beta-lactams) or protein synthesis (e.g., aminoglycosides) are effective against its vegetative cells. However, its ability to form biofilms on catheters or ventilators complicates eradication, requiring rigorous disinfection protocols. For example, a 2% glutaraldehyde solution or hydrogen peroxide gas plasma is recommended for sterilizing contaminated medical equipment. Understanding its vegetative limitations helps tailor strategies to control its spread.

In summary, the absence of spore formation in *S. marcescens* differentiates it from more resilient pathogens, shaping its ecological niche and clinical management. While vegetative growth enables rapid adaptation and colonization, it also exposes the bacterium to environmental threats. This knowledge informs targeted disinfection practices and antibiotic therapies, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria in microbiology.

Mastering Spore: Strategies to Recruit an Epic Team Member

You may want to see also

Clinical Implications of Spore Formation

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is not known to form spores under normal conditions. This characteristic significantly influences its clinical implications, particularly in healthcare settings. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Clostridium difficile, which can persist in the environment for extended periods, S. marcescens relies on its ability to survive on moist surfaces and in water sources. This distinction is critical for infection control strategies, as non-spore-forming bacteria are generally more susceptible to standard disinfection methods.

Understanding the lack of spore formation in S. marcescens allows healthcare providers to tailor their approach to preventing and managing infections. For instance, routine disinfection protocols using alcohol-based solutions or quaternary ammonium compounds are typically effective against this organism. However, its ability to colonize medical devices, such as catheters and respirators, underscores the need for vigilant hygiene practices. Patients with compromised immune systems, particularly those in intensive care units or undergoing chemotherapy, are at higher risk of opportunistic infections, making early detection and intervention crucial.

The clinical implications extend to diagnostic and treatment strategies. Since S. marcescens does not form spores, laboratory identification relies on conventional methods such as Gram staining, biochemical tests, and molecular techniques. Treatment typically involves antibiotics like cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, or carbapenems, depending on susceptibility patterns. However, the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains highlights the importance of antimicrobial stewardship programs to preserve treatment efficacy. For example, in a case of catheter-related bloodstream infection, prompt removal of the device and initiation of appropriate antibiotics within 24 hours can significantly improve outcomes.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation simplifies environmental decontamination efforts but does not diminish the need for proactive measures. Hospitals must ensure regular cleaning of high-touch surfaces, proper maintenance of water systems, and adherence to hand hygiene protocols. For instance, a study in a neonatal intensive care unit demonstrated that daily disinfection of water taps reduced S. marcescens colonization rates by 40%. Such targeted interventions are essential to prevent outbreaks, particularly in vulnerable populations like neonates and the elderly.

In conclusion, while Serratia marcescens does not form spores, its clinical implications demand a nuanced approach to infection prevention and management. Healthcare providers must leverage this knowledge to implement effective strategies, from diagnostic accuracy to environmental control and antimicrobial therapy. By addressing the unique challenges posed by this bacterium, clinicians can mitigate risks and improve patient outcomes in diverse healthcare settings.

How Equisetum Spores Travel: Unveiling Their Unique Movement Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Laboratory Detection of Serratia Spores

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is not typically known for spore formation under standard conditions. However, understanding its potential to produce spore-like structures or survive in harsh environments is crucial for accurate laboratory detection. This distinction is vital because spores are highly resistant to common sterilization methods, whereas vegetative cells are more easily eradicated. Detecting Serratia spores, therefore, requires specialized techniques to differentiate them from their vegetative counterparts and other spore-forming bacteria.

Analytical Approach: The Challenge of Detection

Instructive Steps: Protocols for Detection

To detect Serratia spores in a laboratory setting, begin with selective enrichment media, such as sporulation-inducing agar supplemented with stressors like high salinity or nutrient deprivation. Incubate samples at 37°C for 24–48 hours, then apply heat treatment (e.g., 80°C for 10 minutes) to kill vegetative cells. Streak the surviving cells onto differential media like MacConkey agar, which inhibits Gram-positive spore formers while allowing Serratia colonies to grow. For molecular confirmation, extract DNA and perform PCR targeting Serratia-specific genes, such as the *rpoB* gene. Alternatively, use spore-specific stains like malachite green or fluorescent dyes for microscopic visualization.

Comparative Perspective: Differentiating from True Spores

Unlike true endospores, which are highly refractile and resistant to extreme conditions, Serratia spore-like structures are less robust and may not survive autoclaving. This distinction is critical for laboratory detection, as methods optimized for Bacillus or Clostridium spores may fail to identify Serratia. For instance, while true spores remain viable after exposure to 100°C for 15 minutes, Serratia structures may degrade under such conditions. Comparative analysis using viability assays, such as colony-forming unit (CFU) counts before and after heat treatment, can help differentiate these structures from true spores.

Practical Tips: Avoiding False Positives

False positives in Serratia spore detection often arise from contamination or misidentification of vegetative cells. To minimize errors, maintain strict aseptic techniques during sample collection and processing. Use sterile filters (0.22 μm) to exclude larger particles and reduce background noise. When interpreting results, consider the sample’s origin; Serratia is commonly found in water, soil, and clinical settings, but spore-like structures are rare. Always correlate laboratory findings with clinical or environmental context to ensure accurate reporting.

While Serratia marcescens is not a spore-forming bacterium in the classical sense, its potential to produce spore-like structures under stress conditions necessitates precise detection methods. By combining selective enrichment, molecular techniques, and comparative analysis, laboratories can accurately identify and differentiate these structures. This precision is essential for infection control, environmental monitoring, and research, ensuring that Serratia spores are neither overlooked nor misidentified in critical settings.

Mastering Fungal Spores: Techniques to Activate and Cultivate Successfully

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Serratia marcescens is not a spore-forming bacterium. It is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that does not produce spores.

Yes, Serratia marcescens can survive in various environments due to its ability to produce pigments like prodigiosin and its resistance to desiccation, but it does not form spores for survival.

Serratia marcescens is sometimes mistaken for spore-forming bacteria due to its red pigmentation, which can resemble certain spore-forming species like Bacillus. However, it lacks the ability to form spores.

No, the lack of spore formation does not prevent Serratia marcescens from causing infections. It is an opportunistic pathogen that can survive in hospital environments and cause infections through other means, such as biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance.