The question of whether a spore is a bacteria often arises due to the similarities in their microscopic size and survival mechanisms. However, spores are not bacteria themselves but rather a dormant, highly resistant form produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants as a survival strategy. Bacterial spores, in particular, are formed by specific bacterial species, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, to endure harsh environmental conditions like extreme temperatures, radiation, and desiccation. While spores share some characteristics with bacteria, they are distinct in their structure, function, and life cycle, serving primarily as a protective state rather than an active, metabolizing organism.

What You'll Learn

- Spore vs. Bacterial Cell Structure: Comparing cell walls, membranes, and internal components of spores and bacteria

- Spore Formation Process: How spores are created through sporulation in certain bacteria and fungi

- Spore Resistance Mechanisms: Understanding spores' ability to survive extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and chemicals

- Bacterial Spores vs. Fungal Spores: Key differences in origin, function, and characteristics between bacterial and fungal spores

- Spore Germination Triggers: Factors like nutrients, temperature, and moisture that activate spore germination

Spore vs. Bacterial Cell Structure: Comparing cell walls, membranes, and internal components of spores and bacteria

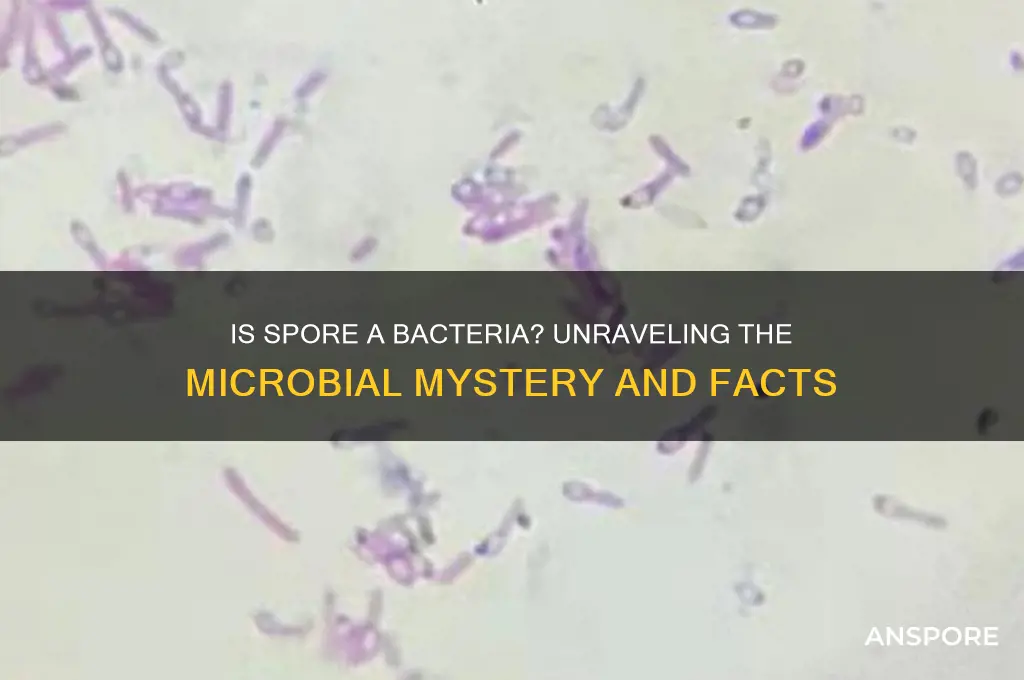

Spores and bacterial cells, though both microscopic entities, exhibit distinct structural differences that define their roles and survival strategies. At the core of this comparison lies the cell wall, a critical component for both. Bacterial cell walls are primarily composed of peptidoglycan, a robust yet flexible polymer that maintains cell shape and protects against osmotic pressure. In contrast, spores, particularly those of fungi and bacteria, often feature a multilayered cell wall enriched with durable compounds like dipicolinic acid and calcium ions. This fortified structure enables spores to withstand extreme conditions, including heat, desiccation, and radiation, far surpassing the resilience of a typical bacterial cell wall.

Membrane composition further highlights the divergence between spores and bacteria. Bacterial cell membranes are fluid phospholipid bilayers embedded with proteins essential for nutrient transport and waste removal. Spores, however, adopt a more rigid membrane structure, often supplemented with additional lipid layers and specialized proteins that minimize permeability. This adaptation reduces metabolic activity to nearly zero, allowing spores to enter a dormant state that can last for centuries. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores have been revived from sediments thousands of years old, a feat no ordinary bacterial cell could achieve.

Internally, the differences become even more pronounced. Bacterial cells house a cytoplasm filled with ribosomes, enzymes, and genetic material, all actively engaged in metabolic processes. Spores, on the other hand, contain a dehydrated cytoplasm with condensed DNA and minimal enzymatic activity. The core of a spore is often surrounded by a protective cortex layer, rich in peptidoglycan, which acts as an additional barrier against environmental stressors. This internal reorganization is a key factor in the spore’s ability to endure conditions that would destroy most bacterial cells.

Understanding these structural disparities is crucial for practical applications, particularly in fields like medicine and food preservation. For example, antibiotics targeting peptidoglycan synthesis, such as penicillin, are effective against actively growing bacteria but ineffective against dormant spores. Similarly, sterilization techniques like autoclaving rely on prolonged exposure to high temperatures to penetrate the spore’s robust cell wall and degrade its internal components. By recognizing the unique architecture of spores and bacteria, scientists can develop more targeted strategies to combat bacterial infections and ensure food safety.

In summary, while both spores and bacterial cells share fundamental features like cell walls and membranes, their structural nuances reflect their distinct survival mechanisms. Bacteria prioritize metabolic activity and growth, whereas spores excel in dormancy and resilience. This comparison not only underscores the diversity of microbial life but also informs practical approaches to managing these organisms in various contexts. Whether in a laboratory or a food processing plant, appreciating these differences is essential for effective control and utilization of microbial entities.

Exploring the Cost of Psychedelic Mushroom Spores in a Syringe

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process: How spores are created through sporulation in certain bacteria and fungi

Spores are not bacteria themselves but rather a resilient, dormant form produced by certain bacteria and fungi to survive harsh conditions. This process, known as sporulation, is a complex, highly regulated mechanism that ensures the organism’s long-term survival. In bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, sporulation is triggered by nutrient depletion, while in fungi such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, it often occurs in response to environmental stressors like desiccation or temperature extremes. Understanding sporulation is crucial, as spores can withstand extreme conditions—heat, radiation, and chemicals—that would destroy their vegetative counterparts.

The sporulation process in bacteria begins with the formation of an asymmetrically positioned septum within the cell, dividing it into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. The forespore is engulfed by the mother cell in a process called engulfment, creating a double-membrane structure. Subsequently, the mother cell synthesizes a thick, protective coat around the forespore, which includes layers like the cortex (rich in peptidoglycan) and the exosporium (an outer proteinaceous layer). This multi-layered structure is key to the spore’s durability. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can survive boiling water for hours, a feat attributed to their robust coat and dehydrated core.

In fungi, sporulation involves the development of specialized structures like sporangia or asci, where spores are produced. For instance, in *Aspergillus*, hyphae differentiate into spore-bearing structures called conidiophores, which release asexual spores (conidia) into the environment. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air, ensuring widespread colonization. Unlike bacterial spores, fungal spores are often haploid and play a direct role in reproduction, though they also serve as survival structures in adverse conditions.

Practical considerations for dealing with spores include their resistance to standard disinfection methods. In healthcare settings, spores of *Clostridioides difficile* require specialized disinfectants like chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 10,000 ppm sodium hypochlorite) to ensure eradication. In food preservation, techniques like autoclaving (121°C for 15–30 minutes) are necessary to destroy bacterial spores, as they can survive pasteurization temperatures. For fungal spores, HEPA filtration systems are effective in controlling airborne dispersal, particularly in immunocompromised environments.

In summary, sporulation is a survival strategy that transforms vulnerable cells into indestructible spores. While bacterial spores focus on endurance through structural complexity, fungal spores balance survival with reproductive efficiency. Recognizing these differences is essential for developing targeted interventions, whether in medical disinfection, food safety, or environmental control. Spores may not be bacteria, but their bacterial and fungal origins highlight the ingenuity of microbial life in overcoming environmental challenges.

Can You Play Spore on Mobile? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Spore Resistance Mechanisms: Understanding spores' ability to survive extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and chemicals

Spores, often mistaken for bacteria, are actually dormant, highly resistant structures produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants. Unlike bacteria, which are active cells, spores are survival specialists, capable of withstanding extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. Their resilience is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation, and understanding their resistance mechanisms offers insights into both biological survival strategies and practical applications in fields like food preservation and space exploration.

One of the most remarkable features of spores is their ability to endure high temperatures. For instance, bacterial endospores, such as those produced by *Clostridium botulinum*, can survive boiling water (100°C) for hours. This heat resistance is attributed to their low water content, which minimizes thermal damage, and the presence of dipicolinic acid, a molecule that stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins. To kill such spores, temperatures exceeding 121°C are required, typically achieved through autoclaving, a process widely used in laboratories and medical settings. This highlights the importance of precise temperature control in sterilization protocols.

Radiation resistance is another extraordinary trait of spores. They can withstand doses of UV light, gamma radiation, and X-rays that would be lethal to most organisms. This resilience stems from their thick, multilayered cell walls and the presence of DNA repair enzymes that quickly fix radiation-induced damage. For example, *Deinococcus radiodurans*, a bacterium known for its spore-like resistance, can survive doses of radiation up to 5,000 grays (Gy), compared to the 5 Gy that is fatal to humans. Such capabilities have sparked interest in using spores as models for developing radiation-resistant technologies, including those for long-duration space missions.

Chemical resistance further underscores the spore’s survival prowess. Spores are impervious to many disinfectants, including ethanol and quaternary ammonium compounds, due to their impermeable outer layers. However, they are not invincible; spores can be inactivated by strong oxidizing agents like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine bleach. For household disinfection, a 10% bleach solution (5,000 ppm chlorine) is effective against spores when applied for at least 10 minutes. This knowledge is crucial for ensuring hygiene in environments where spores pose a risk, such as food processing facilities.

In summary, spores’ resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By studying these mechanisms, we not only gain a deeper understanding of life’s adaptability but also develop practical tools for sterilization, preservation, and exploration. Whether in a laboratory, kitchen, or spacecraft, the lessons from spore resistance are both scientifically fascinating and profoundly useful.

Roses Reproduction: Seeds or Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Rose Propagation

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores vs. Fungal Spores: Key differences in origin, function, and characteristics between bacterial and fungal spores

Spores are often misunderstood as a singular entity, but they represent distinct survival mechanisms across different organisms. To clarify, a spore is not a bacterium itself but rather a dormant, resilient structure produced by certain bacteria and fungi to endure harsh conditions. This distinction is crucial, as bacterial and fungal spores differ significantly in origin, function, and characteristics.

Origin and Formation: A Tale of Two Kingdoms

Bacterial spores, such as those formed by *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are created through a process called sporulation within a single bacterial cell. This process involves the encapsulation of DNA and essential enzymes within a protective layer, often in response to nutrient depletion or environmental stress. In contrast, fungal spores, like those of molds and yeasts, are typically produced externally through specialized structures such as sporangia or asci. For example, *Aspergillus* fungi release conidia, which are asexual spores dispersed via air currents. This external formation highlights a fundamental difference in how these organisms prepare for survival.

Function: Survival Strategies Compared

Both bacterial and fungal spores serve as survival mechanisms, but their functions diverge based on their ecological roles. Bacterial spores are primarily a means of long-term survival, capable of remaining dormant for decades or even centuries. They are highly resistant to heat, radiation, and desiccation, making them a concern in food preservation and sterilization processes. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures, necessitating pressure cooking to ensure food safety. Fungal spores, on the other hand, are often involved in dispersal and colonization. They are less resistant to extreme conditions but excel in rapid dissemination, allowing fungi to colonize new environments quickly. This difference underscores their distinct evolutionary priorities.

Characteristics: Structure and Resistance

Structurally, bacterial spores are more robust, featuring multiple protective layers, including a thick spore coat and cortex. These layers provide resistance to chemicals, enzymes, and physical stressors. Fungal spores, while also durable, lack the same level of complexity. For example, fungal conidia have a simpler cell wall composed primarily of chitin, which offers protection but is less resistant to extreme heat compared to bacterial spores. Additionally, bacterial spores often require specific germination conditions, such as nutrient availability and temperature shifts, whereas fungal spores can germinate under a broader range of environmental cues.

Practical Implications: Identification and Control

Understanding these differences is essential for practical applications. In healthcare, distinguishing between bacterial and fungal spores is critical for infection control. Bacterial spores, such as those of *Clostridioides difficile*, require specialized disinfectants like chlorine bleach, while fungal spores may be controlled with less aggressive agents. In agriculture, managing fungal spore dispersal can prevent crop diseases, whereas bacterial spores may require soil treatment to ensure long-term eradication. For instance, pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds effectively destroys most bacterial spores in milk but may not impact fungal spores, which are less heat-resistant but more prevalent in the environment.

Takeaway: A Nuanced Understanding

While both bacterial and fungal spores are survival structures, their origins, functions, and characteristics reflect their unique evolutionary paths. Bacterial spores prioritize extreme resistance and longevity, whereas fungal spores focus on rapid dispersal and colonization. Recognizing these differences enables targeted strategies for control, whether in medical, agricultural, or industrial settings. This nuanced understanding ensures effective management of spore-related challenges, from food safety to disease prevention.

Mastering Galactic Domination: A Comprehensive Guide to Conquering Spore's Galaxy

You may want to see also

Spore Germination Triggers: Factors like nutrients, temperature, and moisture that activate spore germination

Spores, often mistaken for bacteria due to their microscopic size and resilience, are actually dormant life forms produced by certain plants, fungi, and bacteria. Unlike bacteria, which are single-celled organisms actively metabolizing, spores are inactive survival structures capable of enduring extreme conditions. To transition from dormancy to active growth, spores require specific triggers—a process known as germination. Understanding these triggers is crucial for fields like agriculture, food safety, and medicine, where controlling spore behavior can prevent contamination or promote beneficial growth.

Nutrients act as the first signal for spore germination, providing the energy and building blocks necessary for revival. For bacterial spores, such as those of *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, the presence of specific amino acids like L-valine or inosine can initiate germination. In fungi, like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, simple sugars such as glucose or fructose are often the key. Practical applications include using nutrient-rich media in labs to study spore behavior or ensuring nutrient deprivation in food preservation to prevent spoilage. For instance, canning processes heat food to destroy spores, but residual nutrients can still trigger germination if temperatures aren’t adequately controlled.

Temperature plays a dual role in spore germination, acting as both a trigger and a regulator. Most bacterial spores germinate optimally between 25°C and 37°C, while fungal spores often prefer cooler ranges, such as 15°C to 25°C. However, extreme temperatures can also inhibit germination or even kill spores. For example, pasteurization (72°C for 15 seconds) is effective against many bacterial spores in milk, but *Clostridium botulinum* spores require higher temperatures (121°C) for destruction. In agriculture, soil temperature is monitored to predict fungal spore germination, helping farmers time fungicide applications effectively.

Moisture is the final critical factor, as spores require water to rehydrate and initiate metabolic processes. Bacterial spores, for instance, need at least 30-50% relative humidity to germinate, while fungal spores often require higher levels, around 80-90%. In food preservation, controlling moisture is as vital as temperature—dried foods like jerky or powders have low water activity, preventing spore germination. Conversely, humid environments, such as damp basements, can trigger mold spore germination, leading to health risks like allergies or asthma. Practical tips include using dehumidifiers in storage areas and ensuring proper ventilation to reduce moisture levels.

Combining these triggers—nutrients, temperature, and moisture—creates a precise environment for spore germination, whether to study, control, or exploit their behavior. For instance, in biotechnology, spores of *Bacillus thuringiensis* are germinated under controlled conditions to produce biopesticides. In contrast, food safety protocols focus on eliminating these triggers to prevent contamination. Understanding these factors allows for targeted interventions, such as adjusting storage conditions or designing spore-resistant materials. By manipulating these triggers, we can harness the benefits of spores while mitigating their risks.

Crafting a Facehugger in Spore: Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a spore is not a bacteria itself, but rather a dormant, highly resistant structure produced by certain bacteria (and some fungi and plants) to survive harsh environmental conditions.

No, only specific types of bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, have the ability to form spores as a survival mechanism.

Yes, bacterial spores can cause infections if they germinate into active bacteria under favorable conditions, such as in the human body or in food.

Bacterial spores are highly resistant to heat, radiation, and many disinfectants, requiring extreme conditions like autoclaving or specialized chemicals to destroy them.