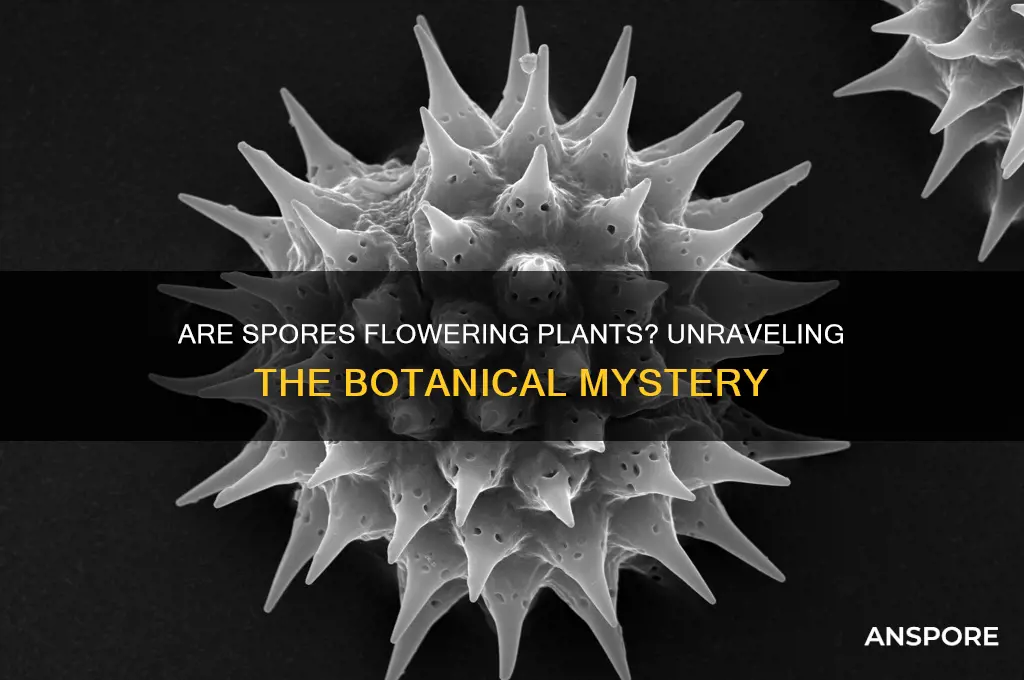

The question of whether spores are associated with flowering plants is a common point of confusion in botany. Flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, are characterized by their ability to produce flowers and seeds enclosed within fruits. In contrast, spores are reproductive structures typically found in non-flowering plants such as ferns, mosses, and fungi. These organisms reproduce through spore dispersal rather than seeds. While flowering plants do not produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle, some plants, like ferns and certain gymnosperms, use spores in their life cycles but do not flower. Understanding this distinction is crucial for accurately categorizing and studying plant species.

What You'll Learn

Are spores produced by flowering plants?

Spores are not produced by flowering plants, a fact that may surprise those unfamiliar with the distinct reproductive strategies of the plant kingdom. Flowering plants, or angiosperms, rely on seeds as their primary means of reproduction. These seeds develop from the ovules after pollination and fertilization, a process that occurs within the flower. In contrast, spores are characteristic of non-flowering plants such as ferns, mosses, and fungi. Understanding this difference is crucial for anyone studying botany or gardening, as it highlights the evolutionary divergence in plant reproduction methods.

To clarify further, let’s examine the reproductive structures involved. Flowering plants produce flowers, which contain reproductive organs like stamens and pistils. Pollen from the stamens fertilizes the ovules in the pistil, leading to seed formation. Spores, on the other hand, are microscopic, unicellular structures produced by sporophytes in non-flowering plants. These spores can disperse over long distances and develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. For example, ferns release spores from the undersides of their fronds, while mosses produce spores in capsules called sporangia. This comparison underscores why flowering plants and spore-producing plants are categorically distinct.

From a practical standpoint, gardeners and horticulturists should recognize that flowering plants propagate through seeds, cuttings, or grafting, not spores. If you’re cultivating roses, sunflowers, or tomatoes, you’ll work with seeds or vegetative parts, not spores. However, if you’re growing ferns or mushrooms, understanding spore dispersal and germination becomes essential. For instance, to propagate ferns, collect spores from mature fronds and sow them on a sterile medium, maintaining high humidity and indirect light. This distinction in propagation methods ensures that efforts are tailored to the specific needs of each plant type.

A persuasive argument can be made for appreciating the diversity of plant reproduction. While flowering plants dominate terrestrial ecosystems and agriculture, spore-producing plants play vital roles in ecological balance. Ferns and mosses, for example, are pioneers in colonizing barren or disturbed lands, preventing soil erosion and creating habitats for other organisms. By recognizing that flowering plants do not produce spores, we gain a deeper respect for the intricate ways plants ensure their survival and contribution to biodiversity. This knowledge encourages conservation efforts and informed gardening practices that support a variety of plant life.

In conclusion, the question of whether spores are produced by flowering plants has a definitive answer: no. Flowering plants rely on seeds, while spores are the domain of non-flowering plants and fungi. This distinction is not merely academic but has practical implications for gardening, botany, and ecology. By understanding these differences, individuals can better cultivate and conserve the diverse plant species that enrich our world. Whether you’re a gardener, student, or nature enthusiast, this knowledge empowers you to engage with plants more thoughtfully and effectively.

Exploring Galactic Adventures: Can You Purchase It Without Spore?

You may want to see also

Differences between spores and seeds in plants

Spores and seeds are both reproductive structures in plants, but they differ fundamentally in their structure, function, and the types of plants that produce them. Spores are typically unicellular or simple multicellular structures produced by non-flowering plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. Seeds, on the other hand, are complex structures exclusive to flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms, containing an embryo, stored food, and protective layers. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence between spore-producing and seed-producing plants.

Consider the lifecycle implications: spores rely on water for dispersal and germination, limiting their survival in dry environments. Seeds, however, are adapted for dormancy and can withstand harsh conditions, often requiring specific triggers like fire, cold, or scarification to germinate. For example, fern spores must land in a moist environment to grow into gametophytes, while a sunflower seed can remain viable in soil for years until conditions are favorable. This adaptability gives seed plants a competitive edge in diverse ecosystems.

From a structural perspective, spores are lightweight and often dispersed by wind or water, lacking the resources to support immediate growth. Seeds, in contrast, are nutrient-rich and encased in a protective coat, sometimes even with mechanisms like wings or hooks for dispersal. A pine cone, for instance, releases seeds with wings to aid wind dispersal, while a dandelion uses a feathery pappus. These differences reflect the contrasting strategies of spore-bearing and seed-bearing plants in ensuring survival and propagation.

Practically, understanding these differences is crucial for horticulture and conservation. Gardeners cultivating ferns must maintain high humidity to mimic spore-friendly conditions, whereas sowing seeds often involves controlled watering and soil preparation. In conservation, spore-bearing plants like mosses are used in soil stabilization, while seed-bearing plants are key to reforestation efforts. Knowing whether a plant reproduces via spores or seeds informs effective care and restoration strategies.

In summary, while both spores and seeds serve reproductive purposes, their disparities in structure, lifecycle, and environmental adaptation underscore the diversity of plant reproduction. Spores thrive in moist, stable environments, relying on simplicity and abundance for survival. Seeds, with their complexity and resilience, dominate diverse habitats, shaping ecosystems from forests to deserts. Recognizing these differences not only enriches botanical knowledge but also guides practical applications in gardening, agriculture, and conservation.

Unlocking Cyborg Parts in Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide to Cybernetic Upgrades

You may want to see also

Do flowering plants use spores for reproduction?

Flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, dominate the plant kingdom with their vibrant blooms and diverse reproductive strategies. However, when it comes to the question of whether they use spores for reproduction, the answer is a definitive no. Flowering plants rely on seeds as their primary means of reproduction, a characteristic that sets them apart from other plant groups like ferns and mosses, which do reproduce via spores. This fundamental difference in reproductive methods highlights the evolutionary divergence between these plant types.

To understand why flowering plants do not use spores, consider the structure and function of their reproductive systems. Angiosperms produce flowers, which contain reproductive organs such as stamens (male) and pistils (female). Pollination, often facilitated by insects or wind, transfers pollen from the stamen to the pistil, leading to fertilization and the formation of seeds. These seeds are encased in protective structures like fruits, which aid in dispersal and germination. Spores, on the other hand, are haploid cells produced by non-flowering plants for asexual reproduction. They are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, allowing plants like ferns to colonize new areas quickly. Flowering plants have evolved a more complex, seed-based system that ensures genetic diversity and survival in varied environments.

A comparative analysis reveals the advantages of seed reproduction over spore reproduction in flowering plants. Seeds contain an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat, providing a head start for the developing plant. This is particularly beneficial in unpredictable climates, where spores might struggle to survive. For example, a sunflower seed can remain dormant in soil for months before germinating under favorable conditions, whereas a fern spore requires immediate moisture to grow. Additionally, seeds allow for the development of more complex plant structures, such as trees and shrubs, which are rare among spore-reproducing plants.

For gardeners and botanists, understanding this distinction is practical. If you’re cultivating flowering plants, focus on seed-saving techniques, such as harvesting mature seeds from dried flower heads and storing them in cool, dry conditions. Avoid attempting to propagate them via spores, as this method is ineffective. For instance, to grow more roses, collect seeds from the rose hips in late autumn and sow them in spring, ensuring the soil is well-drained and lightly covered. In contrast, if you’re working with spore-producing plants like ferns, create a humid environment and sprinkle spores on the soil surface to encourage growth.

In conclusion, while spores are a vital reproductive mechanism for non-flowering plants, flowering plants have evolved to use seeds, a strategy that offers greater resilience and adaptability. This distinction not only defines their biological classification but also shapes their ecological roles and cultivation practices. By recognizing these differences, enthusiasts can better appreciate the diversity of the plant kingdom and apply appropriate techniques to nurture their gardens.

Understanding Clostridium Species: Their Ability to Form Spores Explained

You may want to see also

Examples of non-flowering spore-producing plants

Spore-producing plants, unlike their flowering counterparts, rely on spores for reproduction rather than seeds. These plants, often referred to as cryptogams, lack flowers and instead utilize spores to disperse and propagate. Among the diverse array of non-flowering spore-producing plants, several examples stand out for their unique characteristics and ecological significance.

Ferns: Ancient and Resilient

Ferns are perhaps the most recognizable non-flowering spore-producing plants, with over 10,000 species worldwide. They thrive in moist, shaded environments and reproduce via tiny spores located on the undersides of their fronds. For instance, the Boston fern (*Nephrolepis exaltata*) is a popular houseplant known for its air-purifying qualities. To cultivate ferns indoors, maintain high humidity levels by misting the leaves daily and ensuring the soil remains consistently moist but not waterlogged. Ferns are particularly beneficial for households with limited natural light, as they can tolerate low-light conditions.

Mosses: Miniature Ecosystems

Mosses are another prime example of non-flowering spore-producing plants, often found in dense, carpet-like formations in forests, bogs, and even urban environments. Species like the sphagnum moss (*Sphagnum* spp.) play a critical role in wetland ecosystems by retaining water and providing habitat for various organisms. For gardening enthusiasts, mosses can be used to create living walls or as ground cover in shaded areas. To encourage moss growth, avoid direct sunlight and maintain a damp environment. A practical tip is to blend moss with buttermilk or yogurt and paint the mixture onto surfaces where moss is desired, as the acidity promotes spore germination.

Horsetails: Living Fossils

Horsetails (*Equisetum* spp.) are primitive plants that have remained virtually unchanged for millions of years. These non-flowering plants produce spores at the tips of their cone-like structures and are often found in wet, sandy soils. While some species are considered weeds, others, like the giant horsetail (*Equisetum telmateia*), are cultivated for their architectural appeal in gardens. However, caution is advised when planting horsetails, as they can spread aggressively. To control their growth, plant them in containers buried in the ground to restrict rhizome expansion.

Clubmosses: Unassuming Yet Vital

Clubmosses (*Lycopodium* spp.) are often mistaken for mosses but belong to a distinct group of non-flowering spore-producing plants. They are characterized by their branching stems and spore-bearing cones. Historically, clubmoss spores were used as a flash powder in photography due to their flammable nature. Today, they are valued in horticulture for their ground-covering abilities in shaded areas. When planting clubmosses, ensure the soil is well-draining and rich in organic matter. Avoid overwatering, as excessive moisture can lead to root rot.

In summary, non-flowering spore-producing plants like ferns, mosses, horsetails, and clubmosses offer both ecological and aesthetic value. By understanding their unique characteristics and care requirements, enthusiasts can successfully incorporate these plants into gardens, homes, or conservation efforts. Whether for their historical significance, environmental benefits, or ornamental appeal, these plants underscore the diversity of the plant kingdom beyond flowering species.

Effective Post-Remediation Mold Cleanup: Eliminate Spores and Prevent Regrowth

You may want to see also

Role of spores in plant life cycles

Spores are not exclusive to flowering plants; instead, they are a hallmark of non-flowering plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. These microscopic, single-celled structures serve as the primary means of reproduction and dispersal in such organisms. Unlike flowering plants, which rely on seeds, spore-producing plants follow an alternation of generations, cycling between a sporophyte (spore-producing) and a gametophyte (gamete-producing) phase. This distinction highlights a fundamental divergence in plant life cycles, with spores playing a role akin to seeds but with unique mechanisms and ecological implications.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a prime example of spore-dependent reproduction. The mature fern plant (sporophyte) produces spores on the undersides of its fronds. When released, these spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which are often no larger than a fingernail. These gametophytes are bisexual, producing both sperm and eggs. After fertilization, a new sporophyte emerges, completing the cycle. This process underscores the spore’s dual role: as a dispersal unit and a genetic bridge between generations. For gardeners cultivating ferns, ensuring high humidity and indirect light during the gametophyte stage can enhance spore germination rates, typically within 2–4 weeks.

From an ecological perspective, spores offer advantages that seeds cannot match. Their lightweight, hardy structure allows for wind dispersal over vast distances, enabling colonization of inhospitable environments. For instance, fungi release trillions of spores into the air daily, ensuring survival in diverse habitats. This adaptability contrasts with flowering plants, whose seeds often require specific conditions for germination. However, spores’ reliance on water for fertilization limits their success in arid regions, a trade-off that shapes their distribution. Conservationists studying endangered bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) often collect spores for ex situ preservation, as their resilience makes them ideal for long-term storage.

A comparative analysis reveals that while spores and seeds both facilitate plant reproduction, their strategies differ markedly. Seeds encapsulate an embryo with stored nutrients, providing a head start for the developing plant. Spores, by contrast, are minimalist—a single cell with no reserves, requiring immediate access to moisture and nutrients. This simplicity makes spores highly efficient for rapid colonization but vulnerable to environmental fluctuations. For educators teaching botany, contrasting these strategies can illustrate the evolutionary trade-offs between protection and proliferation. A hands-on activity could involve students observing spore dispersal under a microscope versus seed germination in controlled conditions.

In practical terms, understanding spores’ role in plant life cycles has applications in agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For example, spore-based biofungicides, such as those derived from *Trichoderma* fungi, are used to combat plant pathogens sustainably. These spores outcompete harmful fungi for resources, reducing the need for chemical pesticides. Similarly, spore studies in lichens (symbiotic organisms of fungi and algae) inform climate research, as their sensitivity to environmental changes makes them bioindicators. Whether in a lab or a garden, recognizing spores’ unique contributions to plant diversity enriches our approach to botany and ecology.

How Spore Influences Bug Types: Unraveling the Impact and Effects

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spore-producing plants, such as ferns and mosses, are not flowering plants. They reproduce via spores instead of seeds and flowers.

No, flowering plants (angiosperms) reproduce through seeds and flowers, not spores. Spores are characteristic of non-flowering plants like ferns and fungi.

No, spores and flowers serve different reproductive functions. Spores are used by non-flowering plants for asexual reproduction, while flowers are used by angiosperms for sexual reproduction.

No, plants are classified as either spore-producing (non-flowering) or seed-producing (flowering). They do not produce both spores and flowers.