Determining whether a mushroom is poisonous based on a picture alone can be challenging, as many toxic and edible species closely resemble each other. Factors such as color, shape, gills, and habitat provide clues, but accurate identification often requires additional details like spore color, smell, and microscopic features. Misidentification can lead to severe illness or even fatality, making it crucial to consult expert resources or mycologists when in doubt. Always prioritize caution and avoid consuming wild mushrooms without absolute certainty of their safety.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying poisonous mushrooms

A single bite of the Death Cap mushroom (Amanita phalloid) contains enough toxins to kill a healthy adult. This stark fact underscores the critical importance of accurate identification. While many mushrooms are safe and even nutritious, others harbor deadly poisons. The challenge lies in distinguishing between them, as edible and toxic species often resemble each other closely. For instance, the Death Cap can be mistaken for the edible Paddy Straw mushroom, differing only in subtle features like spore color and the presence of a volva (a cup-like structure at the base).

To identify poisonous mushrooms, start by examining key physical characteristics. Color, shape, and texture are obvious starting points, but they’re not definitive. Instead, focus on less variable traits: gill attachment (are they free, attached, or decurrent?), spore print color (white, black, brown, or pink?), and the presence of a ring or volva. For example, mushrooms with a white spore print and a volva are more likely to belong to the Amanita genus, which includes some of the most toxic species. Always document these features with clear photographs for later reference.

Beyond physical traits, consider the mushroom’s habitat and behavior. Poisonous mushrooms often grow in specific environments, such as under oak or pine trees, where they form mycorrhizal relationships with the roots. Some, like the Destroying Angel (another Amanita species), thrive in woodland areas. Additionally, note any changes in appearance over time. For instance, the Galerina marginata, a toxic look-alike of the edible Honey Mushroom, often develops a rusty-brown spore print and grows on wood rather than in soil. Contextual clues like these can be as crucial as physical traits.

If you’re unsure, avoid consumption entirely. No meal is worth the risk of poisoning. Instead, consult a local mycological society or use reliable field guides and apps that incorporate AI-based identification. However, even these tools have limitations. For instance, the popular app iNaturalist can misidentify species due to user-submitted data errors. Always cross-reference findings with multiple sources and, when in doubt, discard the mushroom. Remember, symptoms of poisoning can appear within 6–24 hours and include gastrointestinal distress, organ failure, or neurological symptoms, depending on the toxin.

Finally, educate yourself through hands-on learning. Attend foraging workshops led by experienced mycologists, who can teach you the nuances of identification in real-world settings. Practice making spore prints and documenting microscopic features using a basic mycology kit. The more you engage with mushrooms directly, the sharper your identification skills will become. While it’s impossible to memorize every species, understanding the patterns and pitfalls of poisonous mushrooms will significantly reduce your risk of a fatal mistake.

Are Bruised Mushrooms Poisonous? Debunking Myths and Ensuring Safety

You may want to see also

Common toxic mushroom species

The Death Cap (*Amanita phalla*) is arguably the most infamous toxic mushroom, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Its elegant appearance—white to greenish cap, slender stem, and volva (cup-like base)—often leads foragers astray. Just 30 grams (about one mushroom) contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney damage in adults. Symptoms appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with vomiting and diarrhea, progressing to organ failure if untreated. Pro tip: Avoid any mushroom with a cup at its base, especially in wooded areas near oak trees, its preferred habitat.

Contrast the Death Cap with the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), a toxin-laden species often mistaken for its edible namesake. Its brain-like, wrinkled cap and meaty texture appeal to novice foragers, but it contains gyromitrin, which breaks down into a toxic compound similar to rocket fuel. Even small quantities (50–100 grams) can cause gastrointestinal distress, seizures, or coma in adults. Boiling reduces but does not eliminate toxins, making it unsafe for consumption. Takeaway: If a morel’s cap is wrinkled or its stem is substantial, discard it immediately.

For a comparative perspective, consider the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) and the Conocybe filaris*, both small, unassuming mushrooms with deadly potential. The Destroying Angel resembles the Death Cap but is pure white, blending seamlessly into forest floors. A single mushroom contains enough amatoxins to be lethal. *Conocybe filaris*, often found in lawns, contains the same toxins but is smaller, making it easier to ingest accidentally, especially by children or pets. Caution: Teach children to avoid touching or tasting any wild mushrooms, and keep pets leashed in areas where these species grow.

Finally, the Galerina marginata, often called the "Autumn Skullcap," thrives on decaying wood and closely resembles edible honey mushrooms. Its toxins, similar to those in the Death Cap, cause severe organ damage within 6–12 hours. A dose of 10–20 grams can be fatal. Foraging tip: Always carry a field guide and cross-reference multiple features (cap color, gill attachment, spore print) before consuming any mushroom. When in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth the risk.

Spotting Deadly Mushrooms: A South African Forager's Safety Guide

You may want to see also

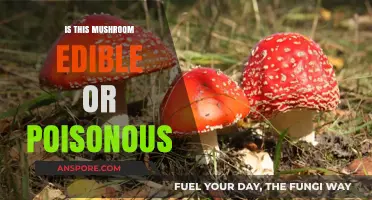

Safe mushroom look-alikes

In the world of fungi, appearances can be deceiving. The Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), one of the most poisonous mushrooms, often masquerades as the edible Paddy Straw Mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*). Both have a similar cap shape and color, but the Death Cap’s white gills and volva (cup-like base) are telltale signs of danger. The Paddy Straw, on the other hand, lacks a volva and has pinkish gills in maturity. Misidentification here can be fatal, as the Death Cap contains amatoxins, which cause liver and kidney failure within 24–48 hours of ingestion. Always check for the volva and gill color before harvesting.

Consider the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), a springtime favorite for some foragers, which closely resembles the edible Morel (*Morchella* spp.). While the False Morel has a brain-like, wrinkled cap, the Morel’s honeycomb structure is distinct. The False Morel contains gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel. Proper preparation—boiling and discarding the water twice—can reduce toxicity, but even then, it’s risky. For beginners, it’s safer to stick to true Morels, which have a hollow stem and a honeycomb cap that’s easy to identify.

The Jack-O’-Lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*) is another deceiver, often mistaken for the edible Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*). Both have wavy caps and grow at the base of trees, but the Jack-O’-Lantern’s bright orange-yellow gills (vs. the Chanterelle’s forked, false gills) and bioluminescent properties are red flags. Ingesting the Jack-O’-Lantern causes severe gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting and dehydration, though it’s rarely fatal. To avoid confusion, examine the gills closely and remember: Chanterelles have a fruity aroma, while Jack-O’-Lanterns smell spicy or unpleasant.

Foraging safely requires more than a quick glance. Take the Galerina Marginata, a small brown mushroom often mistaken for the edible Honey Mushroom (*Armillaria mellea*). Both grow on wood, but *Galerina* contains amatoxins similar to the Death Cap. A key difference is *Galerina*’s spore print color (rusty brown vs. white for *Armillaria*). Always carry a spore print kit and a field guide. If in doubt, leave it out—no meal is worth risking your life.

Lastly, the Little Brown Mushrooms (LBMs) are a forager’s nightmare. Species like the deadly *Conocybe filaris* resemble innocuous LBMs found in lawns. These mushrooms contain the same toxins as the Death Cap but are often overlooked due to their unremarkable appearance. Avoid all LBMs unless you’re an experienced mycologist with access to a microscope. Even experts sometimes hesitate, as microscopic features like spore size and shape are often the only reliable identifiers. When it comes to safe mushroom look-alikes, skepticism and caution are your best tools.

Are California Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Symptoms of mushroom poisoning

Mushroom poisoning symptoms can manifest within minutes to several hours after ingestion, depending on the type of toxin involved. Amanita phalloides, for example, contains amatoxins that may delay symptoms for 6–24 hours, leading to a false sense of security. Early signs often mimic gastrointestinal distress—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain—which can be mistaken for food poisoning. However, unlike typical foodborne illnesses, mushroom poisoning can progress to severe liver and kidney damage, requiring immediate medical attention. Recognizing this delayed onset is critical, as early treatment significantly improves outcomes.

Not all poisonous mushrooms cause the same symptoms. Clitocybe dealbata, which contains muscarine, triggers rapid onset symptoms within 15–30 minutes, including excessive salivation, sweating, tear production, and blurred vision. These effects are due to muscarine’s stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system. In contrast, Psilocybe species, known for their psychoactive compounds, induce hallucinations, confusion, and euphoria, often within 20–40 minutes. While these effects are rarely life-threatening, they can be distressing, especially in children or those unaware of the ingestion. Understanding these symptom profiles helps narrow down the potential culprit when identifying a poisonous mushroom.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning due to their smaller body mass and tendency to ingest unknown substances. For instance, a single Amanita ocreata cap can be fatal to a child, while an adult might require ingestion of multiple mushrooms to experience severe toxicity. If a child or pet exhibits sudden gastrointestinal symptoms or unusual behavior after outdoor exposure, consider mushroom poisoning as a potential cause. Immediate steps include contacting poison control, providing a description or photo of the mushroom, and preserving a sample for identification. Time is of the essence, as some toxins, like orellanine from Cortinarius species, cause irreversible kidney damage within 3–4 days.

To mitigate risks, educate yourself on common poisonous mushrooms in your region and teach children to avoid touching or tasting wild fungi. Apps like iNaturalist or Mushroom Observer can aid in identification, but never rely solely on visual inspection—some toxic and edible species are nearly identical. If poisoning is suspected, avoid home remedies like inducing vomiting or administering activated charcoal without professional guidance. Instead, seek emergency care, bringing the mushroom sample or a detailed description. Hospitals may use treatments like intravenous fluids, silibinin for amatoxin poisoning, or hemodialysis for kidney failure, depending on the toxin involved. Awareness and swift action are key to preventing fatal outcomes.

Are White Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Essential Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Expert mushroom identification tips

A single misidentified mushroom can be fatal, so expert identification is critical. Foragers must move beyond superficial features like color and shape, which can vary widely within species due to environmental factors. Instead, focus on immutable characteristics: spore print color, gill attachment, and the presence of a volva or annulus. For instance, Amanita phalloides, a deadly species, often has a white spore print and a volva at the base, details easily overlooked by novices. Always collect a whole specimen for analysis, as partial samples can lead to incorrect conclusions.

Analyzing habitat and seasonality provides additional context. Certain toxic mushrooms, like the Destroying Angel, thrive in woodland areas under deciduous trees, while edible varieties like chanterelles prefer mossy coniferous forests. Seasonal patterns also matter: spring favors morels, while autumn brings an abundance of Amanita species. Cross-referencing these ecological cues with physical traits significantly reduces misidentification risk. For example, if you find a gilled mushroom in a deciduous forest in late summer, verify the spore print and volva before assuming it’s safe.

Persuasive arguments for using field guides and digital tools cannot be overstated. Apps like iNaturalist or Mushroom Observer leverage AI and community expertise to provide real-time identification assistance. However, these tools should supplement, not replace, traditional methods. Carry a field guide with detailed illustrations and descriptions, and practice making spore prints in the field. For instance, a spore print kit—consisting of a glass pane, paper, and a container—is lightweight and invaluable for confirming species. Combining technology with hands-on techniques ensures a more accurate assessment.

Comparing edible and toxic look-alikes highlights the importance of meticulous observation. Take the case of the edible Parasol Mushroom (Macrolepiota procera) and the toxic Chlorophyllum molybdites. Both have similar cap patterns and grow in grassy areas, but the latter causes severe gastrointestinal distress. Key differentiators include the presence of a movable ring on the Parasol’s stem and its lack of a green spore deposit. Such subtle distinctions underscore why relying on a single characteristic is dangerous. Always examine multiple features before making a judgment.

Descriptive details about mushroom anatomy can transform a novice into a confident identifier. Note the texture of the cap—is it smooth, scaly, or fibrous? Examine the gills: are they free, adnate, or decurrent? Even the smell can be diagnostic; for example, the edible Puffball has a pleasant, earthy aroma, while the toxic Amanita often smells of bleach or raw potatoes. Practice dissecting specimens to observe internal structures like the presence of a veil or the color of the flesh when bruised. These nuanced observations build a robust identification skill set.

Are Gold Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Their Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying poisonous mushrooms from a picture alone is risky and not recommended. Many toxic and edible mushrooms look similar, and details like color, shape, or gills may not be clear in an image. Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide for accurate identification.

While sharing a picture can help, it’s not a reliable way to determine if a mushroom is poisonous. Factors like spore color, smell, and habitat are often needed for identification. Never eat a mushroom based solely on a photo or unverified advice.

Some apps claim to identify mushrooms from photos, but their accuracy varies. These tools should not be trusted for critical decisions like determining edibility. Always cross-reference with expert sources or consult a professional.