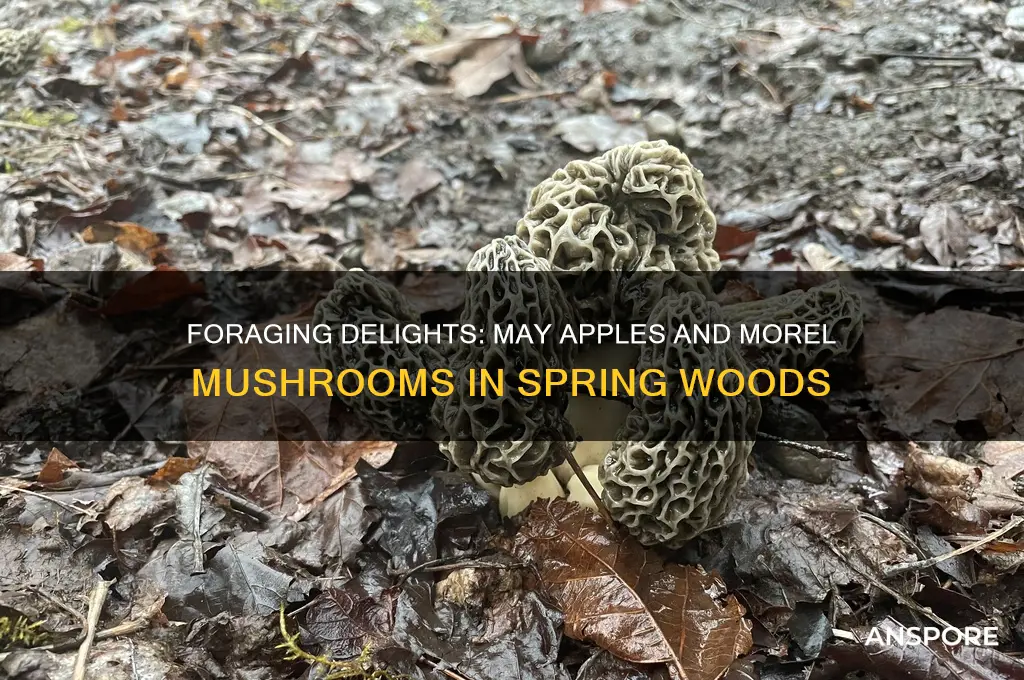

May apples and morel mushrooms are two distinctive springtime treasures that captivate foragers and nature enthusiasts alike. May apples, with their umbrella-like leaves and delicate white flowers, are native to eastern North America and are known for their unique, slightly toxic foliage and edible fruits when ripe. Morel mushrooms, on the other hand, are highly prized for their earthy flavor and honeycomb-like caps, making them a sought-after delicacy in culinary circles. Both species thrive in similar woodland habitats, often appearing together in the early spring, creating a symbiotic relationship with the forest ecosystem. Their ephemeral nature adds to their allure, as they require careful identification and ethical harvesting to ensure sustainability and safety.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | May Apple: Podophyllum peltatum Morel Mushroom: Morchella spp. |

| Family | May Apple: Berberidaceae Morel Mushroom: Morchellaceae |

| Type | May Apple: Perennial herbaceous plant Morel Mushroom: Edible fungus |

| Habitat | May Apple: Deciduous forests, shaded areas Morel Mushroom: Disturbed soil, forests, near trees (e.g., ash, elm, apple) |

| Season | May Apple: Spring (flowers in May) Morel Mushroom: Spring (typically March-May, depending on region) |

| Edibility | May Apple: Fruit is edible in small amounts; rhizome is toxic Morel Mushroom: Edible and highly prized when cooked; raw or undercooked morels can cause upset stomach |

| Appearance | May Apple: Umbrella-like leaves, white flowers, yellow fruit Morel Mushroom: Honeycomb-like cap, hollow stem, sponge-like texture |

| Uses | May Apple: Medicinal (rhizome contains podophyllotoxin, used in wart treatments) Morel Mushroom: Culinary (sautéed, fried, or dried for later use) |

| Toxicity | May Apple: Rhizome is highly toxic; fruit safe in moderation Morel Mushroom: Non-toxic when properly identified and cooked; avoid false morels (Gyromitra spp.) |

| Propagation | May Apple: Spreads via rhizomes and seeds Morel Mushroom: Spores and mycelium; cultivation is challenging and often unpredictable |

| Conservation Status | May Apple: Not endangered, common in suitable habitats Morel Mushroom: Not endangered, but overharvesting can impact local populations |

| Cultural Significance | May Apple: Used in traditional medicine by Native Americans Morel Mushroom: Celebrated in culinary traditions, especially in Europe and North America |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Habitat Overlap: May apples and morels thrive in similar woodland environments with rich, moist soil

- Seasonal Timing: Both emerge in spring, often found together during foraging expeditions

- Ecological Role: May apples provide ground cover; morels decompose organic matter, enriching soil

- Foraging Tips: Look for may apple patches; morels often grow nearby in shaded areas

- Toxicity Awareness: May apples are poisonous; morels are edible but must be cooked thoroughly

Habitat Overlap: May apples and morels thrive in similar woodland environments with rich, moist soil

In the dappled shade of deciduous woodlands, a symbiotic dance unfolds between May apples (*Podophyllum peltatum*) and morel mushrooms (*Morchella* spp.). Both thrive in soils rich in organic matter, slightly acidic (pH 5.5–6.5), and consistently moist—conditions often found under sugar maple, beech, and oak canopies. This habitat overlap isn’t coincidental. May apples, with their umbrella-like leaves, create a microclimate that retains soil moisture and suppresses competing vegetation, indirectly fostering the mycelial networks morels rely on. For foragers, this means a single habitat scan can yield both edible treasures, but caution is paramount: May apple roots are toxic, while morels must be cooked to neutralize trace toxins.

To cultivate this woodland duo, mimic their native environment. Start by amending soil with well-rotted leaf mold or compost to achieve a loamy texture and target pH. Plant May apple rhizomes in early spring, spacing them 12–18 inches apart, and shade with burlap or natural debris until established. Morel spores, notoriously finicky, benefit from inoculating wood chips or sawdust with commercial spawn, then layering this mixture beneath the May apple canopy. Maintain even moisture with drip irrigation or soaker hoses, avoiding overhead watering to prevent fungal diseases. Results aren’t immediate—May apples take 2–3 years to flower, while morels may fruit erratically for 5+ years—but patience yields a self-sustaining ecosystem.

The overlap extends beyond physical habitat. Both species are indicators of undisturbed, mature forests with minimal human intervention. May apples’ presence signals a stable understory, while morels’ mycorrhizal relationships with trees underscore forest health. For conservationists, protecting these habitats means preserving biodiversity: May apples support pollinators with their waxy flowers, while morels contribute to nutrient cycling via their fungal networks. Foragers, take note: Disturbing these ecosystems—overharvesting, trampling soil—threatens both species. Ethical harvesting limits (e.g., collecting no more than 10% of morels in an area) and replanting May apple seeds post-forage are small but impactful practices.

A comparative analysis reveals why this overlap matters. While May apples and morels share habitat preferences, their ecological roles differ. May apples are perennial herbs, storing energy in rhizomes to survive winters, whereas morels are ephemeral fungi, fruiting briefly in spring. This divergence means management strategies must be dual-focused: protecting soil structure for May apples’ root systems while minimizing surface disruption for morels’ delicate mycelium. For landowners, integrating these species into woodland management plans—avoiding heavy machinery, maintaining leaf litter—can enhance both biodiversity and forage potential. The takeaway? Understanding this habitat overlap transforms foraging from a scavenger hunt into a stewardship opportunity.

Descriptively, imagine a spring morning in such a woodland. Sunlight filters through emerald May apple leaves, their veins tracing patterns like miniature maps. Beneath this canopy, the spongy caps of morels emerge, their honeycomb texture blending seamlessly with the forest floor. This scene isn’t just picturesque—it’s a blueprint for coexistence. For educators or parents, this habitat serves as a living classroom: Teach children to identify May apples’ distinctive flowers (a single white bloom in May) as a signpost for potential morel patches. Pair this with a lesson on toxicity—May apple fruits are edible in small quantities when ripe, but unripe fruits and roots are dangerous—to instill respect for nature’s nuances. Practical tip: Carry a pH testing kit and moisture meter when scouting new sites to ensure conditions align with this delicate balance.

Delicious Mushroom Stuffing: Can Bread Be the Perfect Filler?

You may want to see also

Seasonal Timing: Both emerge in spring, often found together during foraging expeditions

Spring’s arrival signals a quiet awakening in the forest, where two elusive treasures—may apples and morel mushrooms—emerge in tandem. This seasonal timing is no coincidence; both thrive in the cool, moist conditions that follow winter’s retreat. Foragers know this as their cue: the unfurling of may apple leaves often marks the beginning of morel season. This symbiotic emergence creates a brief window of opportunity, typically lasting 4–6 weeks, during which both can be found carpeting woodland floors, particularly in deciduous forests with rich, loamy soil. Understanding this timing is crucial; miss it, and you’ll wait another year for nature’s dual bounty.

To maximize your foraging success, start by identifying may apple patches—their umbrella-like leaves are hard to miss. These plants prefer partial shade and often cluster near streams or in areas with decaying wood. Once you’ve located them, scan the surrounding ground for morels. Their honeycomb caps blend seamlessly with leaf litter, but their vertical growth makes them easier to spot than other mushrooms. Pro tip: carry a mesh bag instead of a plastic one; it allows spores to disperse as you walk, ensuring future harvests. Always leave some may apples undisturbed, as their roots are toxic and their presence supports morel growth through shared mycorrhizal networks.

While the timing of their emergence is predictable, environmental factors can shift the window. A warm, wet spring accelerates growth, while a cold, dry one delays it. Foragers in the Midwest, for instance, often find morels peaking in late April to early May, coinciding with may apple sprouting. In contrast, northern regions may see this duo emerge in late May or early June. To stay ahead of the curve, monitor local weather patterns and soil temperatures; morels typically fruit when soil reaches 50–55°F (10–13°C). Apps like iNaturalist or local foraging groups can provide real-time sightings to refine your search.

The ephemeral nature of this pairing demands preparation. Equip yourself with a knife for precise morel harvesting (cut at the base to avoid damaging mycelium) and gloves to handle may apple foliage, which can cause skin irritation. Avoid overharvesting; take only what you’ll use, and leave enough behind to sustain the ecosystem. For culinary enthusiasts, this timing is a gift: morels’ earthy flavor pairs perfectly with may apple’s mild, fruity notes in dishes like wild mushroom risotto or foraged spring salads. Just remember: may apple fruits are the only edible part, and even then, consume in moderation—no more than 2–3 fruits per person to avoid digestive discomfort.

In essence, the springtime convergence of may apples and morels is a forager’s dream, but it’s also a delicate balance of timing, respect, and knowledge. By understanding their seasonal rhythm and ecological interplay, you not only increase your chances of a successful harvest but also contribute to the preservation of these woodland wonders. So, when spring’s first warmth kisses the earth, grab your basket and head to the woods—this fleeting symphony of flora and fungi awaits.

Effective Mice Extermination Tips While Safeguarding Your Mushroom Garden

You may want to see also

Ecological Role: May apples provide ground cover; morels decompose organic matter, enriching soil

In the understory of deciduous forests, May apples (Podophyllum peltatum) form dense mats of foliage, creating a living mulch that conserves soil moisture and suppresses competing weeds. Their broad, umbrella-like leaves intercept rainfall, reducing erosion by slowing water runoff and allowing it to percolate into the soil. This ground cover also moderates soil temperature, protecting the forest floor from extreme heat or cold. By shading the soil, May apples indirectly support a microclimate conducive to the growth of other understory plants and fungi, including morels.

Morels, on the other hand, play a subterranean role as decomposers, breaking down complex organic matter like fallen leaves, wood, and dead roots into simpler nutrients. Their mycelial networks secrete enzymes that dissolve lignin and cellulose, two tough plant compounds resistant to decay. This process releases nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium into the soil, enriching it for other organisms. For example, a single morel mycelium can decompose up to 50 grams of organic matter per square meter annually, depending on environmental conditions. This decomposition not only recycles nutrients but also improves soil structure, enhancing aeration and water retention.

To maximize the ecological benefits of these organisms, consider planting May apples in shaded, moist areas with well-draining soil, spacing them 12–18 inches apart to ensure full ground coverage within 2–3 years. Avoid disturbing their rhizomatous roots, as they are slow to establish. For morels, cultivate their growth by creating a habitat rich in organic debris, such as wood chips or leaf litter, in areas with a pH between 6.0 and 8.0. Morel spores require a symbiotic relationship with trees (e.g., ash, elm, or oak), so plant compatible species nearby. Note that morel fruiting is temperature-sensitive, typically occurring when soil temperatures reach 50–60°F (10–15°C) in spring.

While May apples and morels serve distinct ecological functions, their combined presence amplifies forest health. The ground cover provided by May apples reduces soil compaction and evaporation, creating a stable environment for morel mycelium to thrive. In turn, morels’ nutrient cycling supports the growth of May apples and other plants by replenishing soil fertility. This mutualistic relationship highlights the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems and underscores the importance of preserving native species. For landowners or gardeners, integrating these organisms into woodland management practices can enhance biodiversity, soil health, and even provide edible benefits, as both May apple fruits (in moderation) and morel mushrooms are culinary treasures.

A cautionary note: while May apples and morels are ecologically beneficial, they require careful handling. May apple rhizomes and unripe fruits contain toxic compounds, so avoid ingestion unless properly prepared. Morel identification can be tricky; always confirm their species to avoid poisonous look-alikes. Despite these risks, their ecological roles make them invaluable to forest ecosystems. By understanding and supporting their functions, we can foster resilient habitats that sustain both wildlife and human communities.

Mushrooms and Vitamin C: Unveiling the Nutritional Secrets of Fungi

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Foraging Tips: Look for may apple patches; morels often grow nearby in shaded areas

May apples, with their umbrella-like leaves and distinctive fruit, are more than just a woodland curiosity—they’re a forager’s beacon. These plants thrive in rich, moist soil under partial shade, often forming dense patches in deciduous forests. Here’s the secret: morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and elusive nature, frequently grow in close proximity to may apple colonies. This symbiotic relationship isn’t random; both species favor similar environmental conditions, making may apple patches a strategic starting point for your morel hunt.

To maximize your foraging success, begin by identifying mature may apple patches. Look for areas with well-drained soil and dappled sunlight, typically near streams or on north-facing slopes. Once you’ve located a patch, expand your search to the surrounding shaded zones, particularly where leaf litter is thick and decomposing. Morels often emerge within a 10- to 20-foot radius of may apples, blending into the forest floor with their sponge-like caps. Patience and a keen eye are essential—their camouflage is nature’s way of protecting them from overharvesting.

While this tip increases your odds, it’s not foolproof. Not every may apple patch will yield morels, and environmental factors like temperature, rainfall, and soil pH play a role. Foraging in early spring, when both species are in season, improves your chances. Carry a mesh bag to collect your finds, allowing spores to disperse as you walk. Always leave some morels behind to ensure future growth, and avoid trampling may apple plants, as they’re sensitive to disturbance.

A word of caution: never consume morels or may apples without proper identification. May apple fruits are edible in small quantities when ripe, but the rest of the plant is toxic. Morels, while generally safe, can be confused with false morels, which are poisonous. If in doubt, consult a field guide or experienced forager. By respecting these guidelines, you’ll not only enjoy a bountiful harvest but also preserve the delicate ecosystems that sustain these treasures.

Mushrooms: Nutritional Value and Calories Explained

You may want to see also

Toxicity Awareness: May apples are poisonous; morels are edible but must be cooked thoroughly

May apples, with their umbrella-like leaves and delicate white flowers, are a charming sight in spring woodlands. Yet, their beauty belies a dangerous truth: every part of the plant, from the roots to the unripe green fruit, contains toxic alkaloids. Ingesting even a small amount—as little as one or two raw berries—can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. In extreme cases, particularly in children or pets, consumption can lead to seizures or respiratory failure. The ripe yellow fruit is sometimes considered safe in very small quantities, but this is risky and not recommended. Always err on the side of caution: admire may apples from a distance and never consume any part of the plant.

Contrast the may apple with the morel mushroom, a prized delicacy in the culinary world. Unlike its toxic woodland neighbor, morels are not only edible but highly sought after for their earthy, nutty flavor. However, their safety hinges on proper preparation. Raw morels contain trace amounts of hydrazine toxins, which can cause stomach upset or worse if consumed uncooked. To neutralize these toxins, morels must be thoroughly cooked—boiled for at least 10 minutes, then sautéed or incorporated into dishes. Avoid shortcuts like drying or simply sautéing without boiling, as these methods do not fully eliminate the risk. When prepared correctly, morels are a safe and exquisite addition to any meal, but always source them from a trusted supplier or forager to avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes like false morels.

The juxtaposition of may apples and morels highlights a critical lesson in foraging: nature’s bounty is not always benign. While one plant is entirely off-limits, the other requires careful handling to unlock its potential. For families, educators, or outdoor enthusiasts, this distinction is vital. Teach children to recognize may apples and emphasize the "look but don’t touch" rule. For morel hunters, carry a field guide and practice positive identification, as misidentification can have dire consequences. Cooking morels properly is non-negotiable—think of it as the price of enjoying their unique flavor.

Practical tips can further enhance safety. If you suspect may apple ingestion, contact poison control immediately, especially if symptoms like dizziness or rapid heartbeat appear. For morels, test a small batch first by cooking and consuming a minimal amount, waiting 24 hours to ensure no adverse reaction. Always forage with a knowledgeable guide until you’re confident in your skills. Finally, remember that toxicity in plants and fungi is often dose-dependent, but with may apples, even a small dose can be dangerous. With morels, the risk is manageable but demands respect for the process. By understanding these differences, you can safely navigate the delicate balance between nature’s hazards and its rewards.

Mushrooms: What's the Fuss?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

May apples (Podophyllum peltatum) are perennial plants with umbrella-like leaves and edible fruits, while morel mushrooms are edible fungi known for their honeycomb-like caps. They are not related; may apples are flowering plants, and morels are fungi.

Yes, both may apples and morel mushrooms often thrive in similar environments, such as deciduous forests with rich, moist soil and partial shade. Morel hunters sometimes spot may apples while foraging.

Morel mushrooms are highly prized as a culinary delicacy when properly identified and cooked. May apples have edible fruits, but their roots and unripe fruits are toxic. Always consult a reliable guide before consuming either.