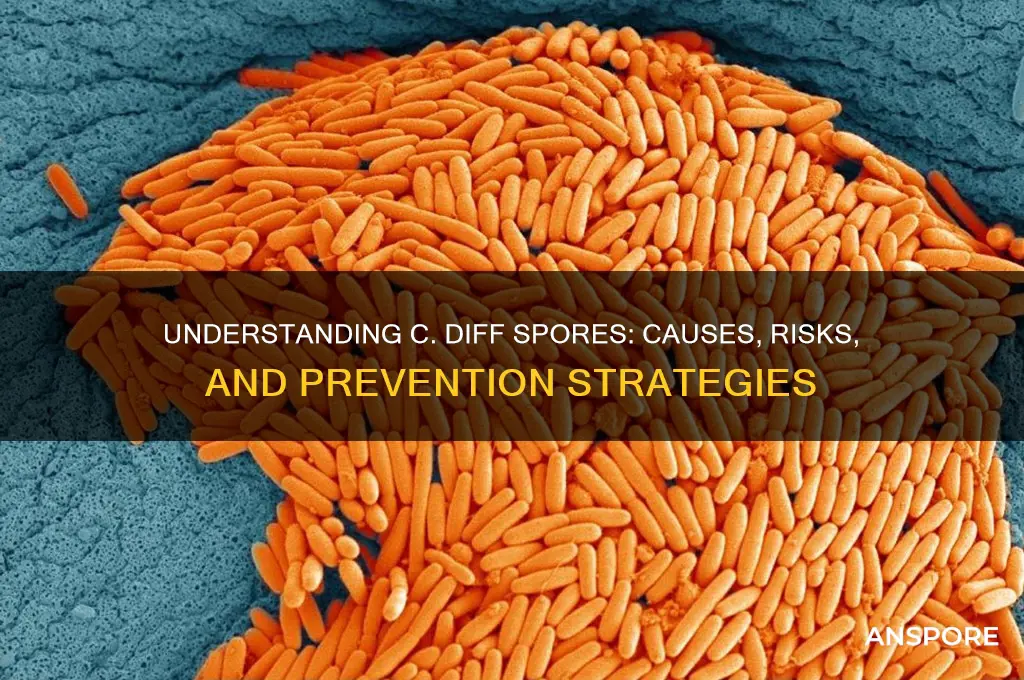

C. diff spores are highly resilient, dormant forms of the bacterium *Clostridioides difficile* (formerly known as *Clostridium difficile*), which can survive for extended periods in harsh environments, including on surfaces and in soil. These spores are a key factor in the transmission of C. diff infections, as they can persist outside the human body and are resistant to many disinfectants and antibiotics. When ingested, the spores can germinate into active bacteria in the gut, particularly when the normal gut flora is disrupted, leading to symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to severe, life-threatening conditions like pseudomembranous colitis. Understanding C. diff spores is crucial for preventing and controlling outbreaks, as they highlight the importance of proper hygiene, infection control measures, and targeted treatment strategies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Spores produced by Clostridioides difficile (C. diff), a gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium. |

| Function | Serve as a dormant, highly resistant form of the bacterium to survive harsh conditions. |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, drying, UV light, disinfectants, and antibiotics. |

| Survival Time | Can survive for months to years in the environment. |

| Infection Risk | Primary cause of C. diff infection (CDI) when ingested by susceptible individuals. |

| Transmission | Spread via fecal-oral route, contaminated surfaces, or healthcare settings. |

| Size | Approximately 0.5 to 1.5 μm in diameter. |

| Shape | Oval or spherical. |

| Location | Found in the intestinal tract of infected individuals or in the environment. |

| Disinfection | Requires spore-specific disinfectants (e.g., bleach solutions with 10% chlorine). |

| Antibiotic Susceptibility | Spores themselves are not affected by antibiotics; vegetative cells are targeted. |

| Germination | Spores germinate into vegetative cells under favorable conditions (e.g., bile salts in the gut). |

| Prevalence | Common in healthcare settings, especially among patients on antibiotics. |

| Symptoms of CDI | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and in severe cases, pseudomembranous colitis. |

| Risk Factors | Antibiotic use, hospitalization, advanced age, and weakened immune system. |

| Prevention | Hand hygiene, environmental disinfection, and judicious antibiotic use. |

What You'll Learn

- C. diff spore structure: Highly resistant, dormant bacterial cells with thick protein coats, surviving harsh conditions

- Spore formation process: Sporulation occurs under stress, transforming vegetative cells into durable spores

- Survival in environment: Spores persist on surfaces for months, resistant to heat, drying, and disinfectants

- Transmission risks: Spread via fecal-oral route, contaminated hands, or surfaces, causing infections in healthcare settings

- Inactivation methods: Spores require strong disinfectants like bleach or UV light for effective elimination

C. diff spore structure: Highly resistant, dormant bacterial cells with thick protein coats, surviving harsh conditions

C. diff spores are the dormant, highly resilient form of *Clostridioides difficile*, a bacterium notorious for causing severe gastrointestinal infections. Unlike active bacterial cells, spores are metabolically inactive, allowing them to withstand extreme conditions that would destroy their vegetative counterparts. This survival mechanism is critical to their persistence in healthcare environments, where they can remain viable on surfaces for months, posing a significant infection control challenge.

The structure of C. diff spores is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation. Encased in a thick protein coat, or exosporium, these spores are shielded from desiccation, heat, and disinfectants. This protective layer is composed of multiple proteins, including cotylase and SASP (spore-associated small acid-soluble proteins), which contribute to their durability. Additionally, the spore’s core contains a dehydrated cytoplasm and highly condensed DNA, further enhancing resistance to environmental stressors such as UV radiation and antibiotics.

Understanding the spore’s structure is crucial for effective disinfection strategies. Standard alcohol-based hand sanitizers, for instance, are ineffective against C. diff spores due to their protein coat’s resistance to alcohol. Instead, healthcare facilities must rely on spore-specific disinfectants like chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 1:10 dilution of household bleach) or sporicides containing hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid. Proper cleaning protocols, including thorough surface disinfection and hand hygiene with soap and water, are essential to breaking the chain of transmission.

For individuals at risk, particularly those over 65 or with compromised immune systems, preventing spore exposure is paramount. Practical tips include avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use, as these drugs disrupt gut flora and create opportunities for C. diff colonization. In healthcare settings, isolation precautions for infected patients, such as dedicated bathrooms and personal protective equipment (PPE), can limit spore spread. At home, laundering soiled linens with hot water and chlorine bleach, and disinfecting high-touch surfaces, can reduce environmental contamination.

In summary, the structure of C. diff spores—characterized by their thick protein coats and dormant state—underpins their ability to survive harsh conditions. This resilience necessitates targeted disinfection methods and proactive prevention measures. By understanding and addressing the unique properties of these spores, both healthcare providers and individuals can mitigate the risk of infection and curb the spread of this formidable pathogen.

Pine Tree Reproduction: Spores or Seeds? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Spore formation process: Sporulation occurs under stress, transforming vegetative cells into durable spores

Under stress, *Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) initiates a remarkable transformation: the sporulation process. This survival mechanism converts fragile, actively growing vegetative cells into resilient spores capable of enduring harsh environments. Unlike their vegetative counterparts, which thrive in the nutrient-rich gut, spores are dormant, metabolically inactive forms encased in a protective protein coat. This coat, composed of multiple layers including an outer exosporium and inner cortex, shields the spore’s genetic material from desiccation, heat, UV radiation, and disinfectants like chlorine. Understanding this process is critical, as spores are the primary vectors of C. diff transmission, surviving on surfaces for months and resisting routine cleaning protocols.

The sporulation process is triggered by nutrient deprivation, often when C. diff exhausts available resources in its environment. This stress signal activates a genetic cascade, initiating a series of morphological changes. First, the cell replicates its DNA and assembles a septum, dividing asymmetrically into a larger mother cell and smaller forespore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, a unique process called engulfment, forming a double-membrane structure. Next, the mother cell synthesizes the spore’s protective layers, including the peptidoglycan cortex and proteinaceous coat, before lysing to release the mature spore. This intricate process, lasting 6–8 hours under laboratory conditions, ensures the spore’s longevity and resistance.

Comparatively, sporulation in C. diff shares similarities with other spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* but differs in key aspects. For instance, C. diff spores lack the calcium dipicolinate found in *Bacillus* spores, yet they possess unique proteins like the S-layer, which enhances surface adhesion. This distinction underscores the need for targeted disinfection strategies. While alcohol-based hand sanitizers are ineffective against C. diff spores, chlorine-based cleaners (e.g., 5,000–10,000 ppm sodium hypochlorite) or sporicides like peracetic acid are recommended for healthcare settings. Proper cleaning protocols, including contact time of 10 minutes for disinfectants, are essential to break the chain of transmission.

Practically, preventing spore formation is as critical as eliminating existing spores. In healthcare, this involves judicious antibiotic use, as disruption of the gut microbiome by broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., clindamycin, fluoroquinolones) creates conditions conducive to C. diff overgrowth and sporulation. For patients at risk, probiotics containing *Lactobacillus* or *Saccharomyces boulardii* may help restore gut flora, though evidence is mixed. In outbreaks, isolating infected patients, using dedicated equipment, and employing barrier precautions (e.g., gloves, gowns) are vital. For surfaces, steam sterilization (autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes) is the gold standard, though impractical for large areas, making chemical disinfection the go-to method.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is C. diff’s evolutionary masterpiece, ensuring its persistence in hostile environments. By understanding this mechanism, healthcare providers and individuals can implement evidence-based strategies to mitigate spore formation and transmission. From antibiotic stewardship to targeted disinfection, every step counts in the battle against this resilient pathogen.

Mastering Oven-Baked Delights: Using Spores for Perfect Homemade Treats

You may want to see also

Survival in environment: Spores persist on surfaces for months, resistant to heat, drying, and disinfectants

C. difficile spores are environmental survivalists, enduring on surfaces for months, unfazed by heat, dryness, or common disinfectants. This resilience makes them a formidable challenge in healthcare settings, where they can silently persist on bed rails, doorknobs, and medical equipment, waiting to infect vulnerable patients. Their ability to withstand routine cleaning protocols underscores the need for specialized disinfection methods, such as using chlorine-based cleaners with a concentration of at least 5,000 ppm, to effectively eliminate these spores.

Consider the implications of this survival prowess in a hospital ward. A single patient with a C. difficile infection can shed millions of spores daily, contaminating surfaces within a 2-meter radius. These spores remain viable, capable of causing infection, even after weeks of exposure to room temperature and low humidity. Standard alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against many pathogens, are powerless against C. difficile spores, emphasizing the critical importance of handwashing with soap and water in healthcare environments.

The resistance of C. difficile spores to disinfectants is particularly concerning. Many commonly used cleaning agents, such as quaternary ammonium compounds, fail to inactivate these spores. This necessitates a shift in disinfection strategies, prioritizing spore-specific agents like bleach solutions. For example, a 1:10 dilution of household bleach (approximately 5,000–8,000 ppm) is recommended for surface decontamination in outbreak settings. However, even with proper disinfection, the spores’ ability to persist in the environment demands rigorous adherence to infection control practices.

In practical terms, preventing C. difficile transmission requires a multi-faceted approach. Healthcare facilities should implement contact precautions for infected patients, including the use of gloves and gowns, and ensure that environmental cleaning protocols are both thorough and spore-specific. For high-risk areas, such as patient rooms and bathrooms, daily disinfection with chlorine-based cleaners is essential. Additionally, educating staff and patients about the importance of hand hygiene can significantly reduce the risk of spore transmission. Understanding the environmental tenacity of C. difficile spores is not just an academic exercise—it’s a critical step in safeguarding public health.

Mastering Fungal Spore Harvesting: Techniques for Successful Collection and Storage

You may want to see also

Transmission risks: Spread via fecal-oral route, contaminated hands, or surfaces, causing infections in healthcare settings

C. difficile spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving on surfaces for months, making them a persistent threat in healthcare environments. These spores are the dormant form of *Clostridioides difficile*, a bacterium that causes severe diarrhea and colitis, particularly in individuals with disrupted gut microbiota. Understanding their transmission risks is crucial for preventing outbreaks, especially in hospitals and long-term care facilities where vulnerable populations reside.

The fecal-oral route is the primary pathway for C. difficile transmission. Spores shed in feces can contaminate hands, medical equipment, or environmental surfaces. Healthcare workers, patients, or visitors who touch these surfaces and then their mouths or mucous membranes inadvertently ingest the spores. This is why hand hygiene is non-negotiable in healthcare settings. The CDC recommends using soap and water instead of alcohol-based sanitizers, as alcohol does not effectively kill C. difficile spores. A 20-second handwashing protocol, focusing on fingernails, fingertips, and wrists, is essential after contact with patients or high-touch surfaces like bed rails, doorknobs, and toilets.

Contaminated surfaces act as silent carriers of C. difficile spores. Studies show that up to 50% of hospital room surfaces can remain contaminated even after routine cleaning. Enhanced disinfection protocols, such as using EPA-approved spore-killing agents like chlorine bleach (1:10 dilution of 5.25–6.15% sodium hypochlorite), are critical. Pay special attention to frequently touched areas and use disposable cleaning materials to avoid cross-contamination. For high-risk areas, consider ultraviolet (UV) light disinfection as an adjunct to manual cleaning.

In healthcare settings, the risk of transmission escalates due to the proximity of immunocompromised patients and frequent use of antibiotics, which disrupt gut flora and increase susceptibility to C. difficile infection (CDI). Patients aged 65 and older, those on prolonged antibiotic therapy, and individuals with comorbidities are at highest risk. Isolation precautions, such as placing CDI patients in private rooms or cohorting them, can limit spread. Healthcare providers must wear gloves and gowns during patient care and change them between patients to prevent spore transfer.

Breaking the chain of transmission requires a multifaceted approach. Educate staff and patients about the risks of C. difficile and the importance of hand hygiene. Implement contact precautions consistently and ensure cleaning protocols are rigorously followed. By addressing transmission risks at every level—from handwashing to surface disinfection—healthcare facilities can significantly reduce the incidence of CDI and protect vulnerable populations.

Maximize Your Spore Galactic Adventures: Tips for Epic Space Exploration

You may want to see also

Inactivation methods: Spores require strong disinfectants like bleach or UV light for effective elimination

C. difficile spores are notoriously resilient, surviving on surfaces for months and resisting many common cleaning agents. This resilience stems from their tough outer coating, which protects the dormant bacterium within. To effectively eliminate these spores, stronger measures are required, and this is where disinfectants like bleach and UV light come into play.

Unlike bacteria in their active vegetative state, C. diff spores are metabolically inactive, making them less susceptible to antibiotics and standard disinfectants. Their ability to withstand harsh conditions, including heat and desiccation, necessitates the use of potent agents that can penetrate their protective layers and disrupt their cellular structure.

Bleach: A Time-Tested Solution

Sodium hypochlorite, commonly known as bleach, is a powerful disinfectant effective against C. diff spores. A solution of 1:10 household bleach to water (approximately 5,000-8,000 ppm available chlorine) is recommended for surface disinfection. It's crucial to allow sufficient contact time, typically 10 minutes, for the bleach to penetrate the spore's protective coat and inactivate the bacterium. Remember, bleach is corrosive and should be handled with gloves and adequate ventilation.

Never mix bleach with ammonia or other cleaning agents, as this can produce toxic fumes.

UV Light: A Chemical-Free Alternative

Ultraviolet (UV) light, specifically UV-C radiation (254 nm), offers a chemical-free method for spore inactivation. UV-C light damages the DNA within the spore, preventing it from replicating. This method is particularly useful in healthcare settings where chemical disinfectants may be undesirable due to patient sensitivities or the risk of corrosion. However, UV light's effectiveness depends on direct exposure, meaning shadows and surface irregularities can limit its reach.

Choosing the Right Method

The choice between bleach and UV light depends on the specific situation. Bleach is cost-effective and readily available, making it suitable for most surface disinfection needs. UV light, while more expensive initially, offers a chemical-free option ideal for sensitive environments. Regardless of the method chosen, thorough cleaning to remove organic matter before disinfection is crucial for optimal spore inactivation.

Understanding Mold Spore Size: Microscopic Dimensions and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

C. diff spores are the dormant, highly resilient forms of the bacterium *Clostridioides difficile*. These spores are produced by the bacteria as a survival mechanism and can withstand harsh environmental conditions, including heat, dryness, and many disinfectants.

C. diff spores spread primarily through fecal-oral transmission. They can contaminate surfaces, hands, and objects after being shed in the stool of an infected person. Once ingested, the spores can germinate into active bacteria in the gut, potentially causing infection.

C. diff spores are difficult to eliminate because they are resistant to routine cleaning agents and alcohol-based sanitizers. They require specialized disinfectants, such as bleach solutions, and thorough cleaning to be effectively removed from surfaces. Their durability allows them to persist in environments for weeks or even months.