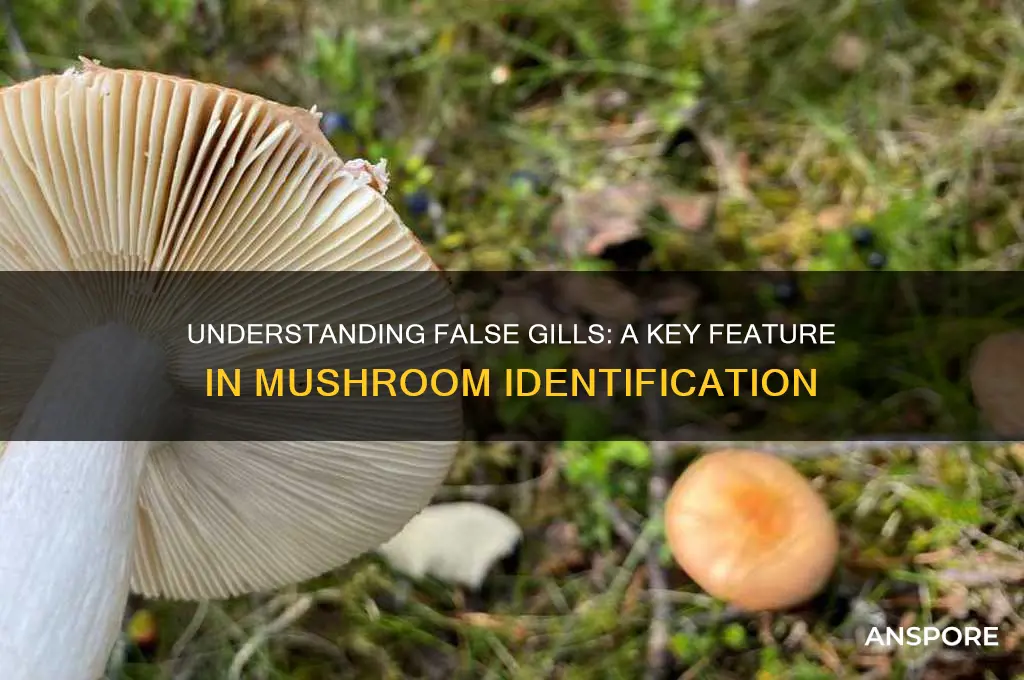

False gills on mushrooms are a distinctive feature found in certain species, particularly within the genus *Clitocybe* and related groups. Unlike true gills, which are thin, blade-like structures attached to the stem and cap of a mushroom, false gills are thicker, often forked or interconnected, and typically extend down the stem. They are not directly involved in spore production, which is the primary function of true gills. Instead, false gills serve as a diagnostic characteristic for identification, helping mycologists and enthusiasts distinguish these mushrooms from others. Their presence is a key feature in classifying species within the *Clitocybe* genus and understanding their evolutionary relationships.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | False gills are structures on mushrooms that resemble true gills but are not attached to the stem and do not produce spores. |

| Location | Found on the underside of the mushroom cap, similar to true gills. |

| Attachment | Not directly attached to the stem; often forked, interconnected, or descending. |

| Function | Do not play a role in spore production; primarily serve as a morphological feature for identification. |

| Types | Include forked gills (e.g., in Chanterelles), folded or wrinkled structures (e.g., in False Morels), and vein-like formations (e.g., in Hydnoid fungi). |

| Associated Genera | Commonly found in genera like Cantharellus (Chanterelles), Gyromitra (False Morels), and Hydnum (Hedgehogs). |

| Identification | Key for distinguishing between similar-looking mushroom species, especially in foraging and taxonomy. |

| Texture | Can vary from smooth to ridged, depending on the species. |

| Color | Ranges widely, often matching or contrasting with the cap color. |

| Spores | Absent; spores are produced on true gills or other structures like spines or pores. |

| Ecological Role | Primarily structural, aiding in species classification rather than reproduction or nutrient exchange. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- False gills vs. true gills: structural differences and identification tips for mushroom enthusiasts

- Types of false gills: ridges, folds, and veins found on various mushroom species

- Mushrooms with false gills: common examples like Chantrelles, Crust fungi, and more

- Ecological role: how false gills contribute to spore dispersal and mushroom survival

- False gills in taxonomy: their significance in classifying and identifying mushroom species

False gills vs. true gills: structural differences and identification tips for mushroom enthusiasts

False gills and true gills are distinct structures found on mushrooms, and understanding their differences is crucial for accurate identification. True gills, also known as lamellae, are thin, blade-like structures that radiate outward from the stem and are attached to the cap (pileus) of the mushroom. They are the primary site of spore production in many fungi. True gills are typically flexible, closely spaced, and run continuously from the stem to the cap edge. In contrast, false gills, often found in mushrooms of the genus *Chanterelle* and some polypores, are not directly attached to the stem or may appear forked, branched, or irregularly shaped. False gills are usually thicker and more rigid compared to true gills, and they often have a vein-like or wrinkled appearance.

Structurally, true gills are supported by a subhymenium, a layer of tissue beneath the spore-bearing surface, which allows them to be thin and delicate. They are uniformly attached to the stem and cap, creating a consistent pattern. False gills, however, lack this uniform attachment and may appear to be part of the cap's flesh or extend irregularly. For example, in chanterelles, the false gills are actually folds of the cap tissue itself, giving them a wavy or forked appearance. This distinction is essential for mushroom enthusiasts, as it helps differentiate between species that may otherwise look similar.

One key identification tip is to examine how the gills or gill-like structures attach to the stem. True gills will typically be narrowly attached or run down the stem (adnate), while false gills may appear to blend into the cap or stem without a clear point of attachment. Additionally, true gills are usually thinner and more numerous, whereas false gills are often fewer, thicker, and more widely spaced. Observing the color and texture can also be helpful; true gills often match the color of the cap or have a distinct contrast, while false gills may have a more blended or irregular appearance.

Another important feature to note is the presence of cross-veins or forking in false gills, which is uncommon in true gills. For instance, chanterelles have false gills that are often forked or anastomosing (interconnecting), a characteristic that is absent in mushrooms with true gills. Mushroom enthusiasts should also consider the habitat and associated trees, as certain species with false gills, like chanterelles, are often mycorrhizal and found near specific tree species.

In summary, distinguishing between false gills and true gills requires careful observation of attachment, structure, and overall appearance. True gills are uniformly attached, thin, and blade-like, while false gills are thicker, irregularly shaped, and often part of the cap tissue. By focusing on these structural differences and using identification tips such as attachment type, spacing, and forking, mushroom enthusiasts can accurately differentiate between species and deepen their understanding of fungal diversity.

Mushroom Compost: Spreading and Gardening Benefits

You may want to see also

Types of false gills: ridges, folds, and veins found on various mushroom species

False gills on mushrooms are structures that resemble true gills but are not directly involved in spore production. Instead, they are formed by the arrangement of tissue in ways that create ridges, folds, or veins on the undersurface of the mushroom cap. These structures can vary widely among species and are often key characteristics used in mushroom identification. Understanding the types of false gills—ridges, folds, and veins—is essential for distinguishing between different mushroom species and appreciating their morphological diversity.

Ridges are one of the most common forms of false gills. They appear as raised, linear structures that run parallel to each other on the undersurface of the cap. Unlike true gills, which are thin and blade-like, ridges are thicker and more robust. For example, species in the genus *Gomphidius* often feature prominent ridges that are forked or interconnected, giving them a gill-like appearance. These ridges are not individual structures but extensions of the cap tissue, and they do not bear spores directly. Ridges can vary in color, spacing, and thickness, providing important clues for identification.

Folds are another type of false gill, characterized by wavy or undulating tissue that creates a pleated appearance. Folds are often softer and more flexible than ridges, and they may appear irregular or uneven. The genus *Marasmius* includes species with distinct folds that can be closely or widely spaced. These folds are not attached to the stem and may extend only partway down the cap, unlike true gills, which typically extend fully from the cap to the stem. Folds can be particularly challenging to distinguish from true gills, especially in young or immature specimens.

Veins represent a third type of false gill, where the undersurface of the cap is divided into a network of vein-like structures. These veins are often anastomosing, meaning they branch and reconnect to form a complex pattern. Species in the genus *Phallaceae*, such as the stinkhorns, exhibit veined structures that are highly distinctive. Unlike ridges or folds, veins are typically thinner and more intricate, resembling the veins of a leaf. Veins are not involved in spore dispersal but contribute to the overall structure and appearance of the mushroom.

Each type of false gill—ridges, folds, and veins—serves as a diagnostic feature for identifying mushroom species. For instance, the presence of ridges is a hallmark of the genus *Gomphidius*, while folds are characteristic of many *Marasmius* species. Veins, on the other hand, are often associated with unusual or exotic mushrooms like the stinkhorns. By carefully examining these structures, mycologists and enthusiasts can differentiate between species that might otherwise appear similar. Understanding the nuances of false gills enhances our ability to classify and appreciate the remarkable diversity of fungi in the natural world.

Cleaning Mushrooms: To Wash or Not?

You may want to see also

Mushrooms with false gills: common examples like Chantrelles, Crust fungi, and more

False gills are a distinctive feature found in certain mushrooms, often leading to confusion among foragers and mycology enthusiasts. Unlike true gills, which are blade-like structures that radiate from the stem and are typical in many agaric mushrooms, false gills are not directly attached to the stem. Instead, they are formed by the folding or branching of the mushroom’s flesh, creating a gill-like appearance. This unique structure is a key identifier for several mushroom species, including Chantrelles, Crust fungi, and others. Understanding false gills is essential for accurate mushroom identification and appreciating the diversity of fungal morphology.

One of the most well-known mushrooms with false gills is the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius* and related species). Chanterelles are prized for their fruity aroma and meaty texture, making them a favorite among chefs and foragers. Their false gills are forked, wavy, and run down the stem, blending seamlessly with the cap. These structures are not individual gills but extensions of the cap’s tissue, creating a ridged or veined appearance. This feature, combined with their golden-yellow color, makes chanterelles relatively easy to identify in the wild. However, it’s crucial to distinguish them from look-alikes like the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, which has true gills and is toxic.

Crust fungi, or resupinate fungi, are another group that often exhibits false gills. These mushrooms grow flat against wood or other substrates, resembling a crust or thin layer. Species like *Gloeophyllum sepiarium* and *Phlebia radiata* have false gills that appear as radiating folds or ridges on their undersides. Unlike the more robust false gills of chanterelles, these are often delicate and closely spaced, giving the fungus a textured appearance. Crust fungi are primarily wood-decay organisms and play a vital role in forest ecosystems, though they are less commonly harvested for culinary use.

Beyond chanterelles and crust fungi, other mushrooms with false gills include species in the genus Hydnum, such as the Hedgehog Mushroom (*Hydnum repandum*). Instead of gills, these mushrooms have spines or teeth-like structures that hang downward from the cap, which are technically a form of false gill. These spines are soft and easily broken, unlike the tougher spines of hydnoid fungi. Hedgehog mushrooms are edible and highly regarded for their flavor, though they require careful identification to avoid toxic look-alikes like the Tooth Hedgehog (*Hydnellum peckii*).

Identifying mushrooms with false gills requires attention to detail and an understanding of their unique structures. Key features to look for include the attachment of the gill-like structures to the stem, their texture, and overall arrangement. For example, false gills in chanterelles are forked and blend with the stem, while those in crust fungi are more subtle and part of a flat, resupinate body. By familiarizing oneself with these characteristics, foragers can confidently distinguish false-gilled mushrooms from their true-gilled counterparts and appreciate the fascinating diversity of fungal forms. Always consult a field guide or expert when in doubt, as accurate identification is crucial for safety and enjoyment.

Cleaning and Cooking Dryad's Saddle Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ecological role: how false gills contribute to spore dispersal and mushroom survival

False gills, a distinctive feature found on certain mushroom species, play a crucial ecological role in spore dispersal and overall mushroom survival. Unlike true gills, which are thin, blade-like structures attached directly to the stem, false gills are formed by the splitting or forking of the flesh of the mushroom cap. This unique structure creates a larger surface area for spore production and release. When spores are produced on the surface of false gills, they are more exposed to air currents, increasing the likelihood of being carried away from the parent mushroom. This enhanced exposure is vital for spore dispersal, as it allows mushrooms to colonize new areas and ensure the survival of their species.

The intricate design of false gills facilitates efficient spore release, a critical process for mushroom reproduction. As air moves over the convoluted surface of the false gills, it creates turbulence that helps dislodge spores more effectively than smooth surfaces. This mechanism is particularly advantageous in environments with limited air movement, such as dense forests or understory habitats. By maximizing spore dispersal even in still conditions, false gills enable mushrooms to propagate successfully across diverse ecosystems. This adaptability is essential for the survival and proliferation of mushroom species in various ecological niches.

False gills also contribute to mushroom survival by optimizing spore production and longevity. The increased surface area provided by false gills allows for a higher density of spore-producing cells, known as basidia. This results in a greater number of spores being generated per mushroom, enhancing the chances of successful colonization. Additionally, the structure of false gills can protect spores from premature release or damage caused by environmental factors such as rain or physical disturbance. By safeguarding spores until they are ready for dispersal, false gills ensure that mushrooms can reproduce effectively even in challenging conditions.

Another ecological benefit of false gills is their role in attracting spore-dispersing agents. The unique appearance and texture of false gills can make mushrooms more noticeable to animals, insects, or water flow, which may inadvertently carry spores to new locations. For example, certain insects or small mammals might be drawn to the mushroom for shelter or food, picking up spores on their bodies in the process. Similarly, rainwater flowing over false gills can transport spores to nearby soil or substrates, aiding in local dispersal. This passive dispersal mechanism complements air-based dispersal, further enhancing the ecological success of mushrooms with false gills.

In summary, false gills are a key adaptation that significantly contributes to spore dispersal and mushroom survival. By increasing surface area, facilitating spore release, optimizing production, and attracting dispersing agents, false gills ensure that mushrooms can effectively reproduce and colonize new habitats. Their ecological role highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of fungi in overcoming the challenges of immobility and environmental variability. Understanding the function of false gills not only sheds light on mushroom biology but also underscores their importance in maintaining fungal diversity and ecosystem health.

Mushroom Powder: A Healthy MSG Alternative?

You may want to see also

False gills in taxonomy: their significance in classifying and identifying mushroom species

False gills, a distinctive feature in certain mushroom species, play a crucial role in the taxonomy and identification of fungi. Unlike true gills, which are blade-like structures attached to the stem and cap of mushrooms, false gills are formed by the splitting or forking of the flesh of the cap itself. This unique characteristic is particularly prominent in species belonging to the genus *Gomphidius* and *Chroogomphus*, where false gills are a defining trait. In taxonomy, the presence or absence of false gills is a key diagnostic feature that helps mycologists differentiate between closely related species. By examining the structure and arrangement of these false gills, taxonomists can classify mushrooms with greater precision, ensuring accurate identification and placement within the fungal kingdom.

The significance of false gills in taxonomy extends to their morphological consistency within specific genera. For instance, in the genus *Gomphidius*, false gills are typically thick, forked, and decurrent (extending down the stem), providing a clear distinction from true gills found in other genera like *Agaricus*. This consistency allows taxonomists to use false gills as a reliable character in identification keys and phylogenetic studies. Moreover, the development of false gills is often linked to specific ecological relationships, such as mycorrhizal associations with trees. Understanding these relationships further enhances the taxonomic value of false gills, as they can provide insights into the evolutionary history and ecological niche of the mushroom species in question.

In the field, false gills serve as a practical tool for mushroom enthusiasts and mycologists alike. Their distinctive appearance—often described as veiny or forked—makes them easily recognizable even to those with limited experience. For example, the *Gomphidius glutinosus*, commonly known as the slimy spike-cap, has false gills that are not only visually striking but also aid in distinguishing it from similar-looking species. This ease of identification is particularly important in regions with diverse fungal flora, where accurate classification can be challenging. By focusing on false gills, collectors can quickly narrow down the possibilities and avoid misidentification.

From a taxonomic perspective, the study of false gills also contributes to our understanding of fungal diversity and evolution. Comparative analyses of false gill structures across different species have revealed patterns of adaptation and speciation. For instance, variations in the thickness, color, and branching of false gills can indicate genetic divergence or responses to environmental pressures. Such observations are invaluable for constructing phylogenetic trees and tracing the evolutionary pathways of mushroom genera. Additionally, the presence of false gills in certain lineages suggests convergent evolution, as similar structures have independently developed in unrelated groups, highlighting the complexity and richness of fungal morphology.

In conclusion, false gills are a taxonomically significant feature that aids in the classification and identification of mushroom species. Their unique morphology, ecological associations, and evolutionary implications make them a focal point in mycological studies. By incorporating the analysis of false gills into taxonomic frameworks, scientists can enhance the accuracy and depth of fungal classifications. For both professionals and amateurs, recognizing and understanding false gills opens doors to a deeper appreciation of the diversity and complexity of the fungal world. As research continues to uncover the intricacies of these structures, their role in taxonomy will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone of mushroom identification and classification.

Mushrooms: Heartburn Trigger or Healthy Treat?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

False gills are structures found on some mushrooms that resemble true gills but are not attached to the stem in the same way. They are often formed by folds or ridges on the underside of the cap and are characteristic of certain mushroom families, such as the Chanterelles.

True gills are thin, blade-like structures that attach directly to the stem and run parallel to each other under the mushroom cap. False gills, on the other hand, are more irregular, often forked or vein-like, and do not attach to the stem in a consistent manner.

Mushrooms in the Cantharellaceae family, such as Chanterelles, are well-known for having false gills. Other examples include species in the Gomphaceae family, like the pig's ears mushroom (Gomphus clavatus).

Yes, false gills are a distinctive feature that can help identify certain mushroom species, particularly Chanterelles. However, they should be used in conjunction with other characteristics, such as color, habitat, and spore print, for accurate identification.

![Organized Living: Solutions and Inspiration for Your Home [A Home Organization Book]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71mgkA5jiCL._AC_UY218_.jpg)