The underside of mushrooms, often overlooked yet fascinating, is known as the gill or pore region, depending on the species. In most common mushrooms, this area consists of thin, blade-like structures called gills, which radiate outward from the stem and serve as the primary site for spore production. In contrast, some mushrooms, like boletes, have a spongy layer of pores instead of gills, which perform the same function. Understanding this part of the mushroom is crucial for identification, as it varies widely among species and plays a key role in their reproductive cycle.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mushroom Anatomy Basics: Understanding the structure and terminology of mushrooms, including the bottom side

- Gills vs. Pores: Identifying if the bottom side has gills or pores for spore release

- Technical Term Hymenium: The spore-bearing surface on the bottom side of mushrooms

- Stipe Attachment Types: How the stem connects to the bottom side (e.g., central, off-center)

- Edibility and Identification: Why knowing the bottom side is crucial for safe mushroom foraging

Mushroom Anatomy Basics: Understanding the structure and terminology of mushrooms, including the bottom side

Mushroom anatomy is a fascinating subject that helps both enthusiasts and mycologists understand the intricate structure of these fungi. One of the most commonly asked questions is, "What are the bottom side of mushrooms called?" The bottom side of a mushroom, often the most visually striking part, is known as the underside or hymenium. This area is crucial for the mushroom's reproductive function and is characterized by its spore-bearing structures. Understanding this part of the mushroom is essential for identification and cultivation.

The hymenium is typically located on the gills, pores, or teeth, depending on the mushroom species. Gills are the most common type of hymenium and appear as thin, blade-like structures radiating from the stem. They are found in many familiar mushrooms, such as the button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*). Pores, on the other hand, are small openings found on the underside of mushrooms in the Boletaceae family, like the porcini mushroom. These pores release spores and give the mushroom a spongy appearance. Teeth, less common but equally important, are found in species like the lion's mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), where the hymenium forms tooth-like projections.

The stem or stipe supports the mushroom's cap and connects it to the ground or substrate. While the stem is not part of the underside, it plays a vital role in the mushroom's structure, providing stability and allowing nutrients to flow between the mycelium and the fruiting body. The cap or pileus is the top part of the mushroom, often the most visible and colorful, but it is the underside that holds the key to the mushroom's reproductive capabilities.

Understanding the terminology of mushroom anatomy is crucial for accurate identification. For instance, the veil is a membrane that often covers the gills or pores in young mushrooms. As the mushroom matures, the veil may tear, leaving remnants like a ring on the stem or patches on the cap. The annulus, or ring, is a remnant of the partial veil, while the volva is a cup-like structure at the base of the stem, typically found in Amanita species. These features, combined with the characteristics of the underside, help distinguish between edible and toxic mushrooms.

In summary, the bottom side of a mushroom, referred to as the hymenium, is a critical component of its anatomy. Whether it consists of gills, pores, or teeth, this area is responsible for spore production and dispersal. Familiarizing oneself with these structures and their associated terminology is essential for anyone interested in mushrooms, whether for foraging, cultivation, or scientific study. By mastering mushroom anatomy basics, one can better appreciate the complexity and beauty of these remarkable organisms.

Popcorn Portions: Cups in 8 oz of Mushroom Popcorn

You may want to see also

Gills vs. Pores: Identifying if the bottom side has gills or pores for spore release

When examining the bottom side of mushrooms, you’ll typically encounter one of two structures responsible for spore release: gills or pores. These features are crucial for identifying mushroom species and understanding their reproductive mechanisms. Gills are thin, blade-like structures that radiate outward from the stem, resembling the ribs of an umbrella. They are commonly found in mushrooms belonging to the Agaricales order, such as button mushrooms and chanterelles. In contrast, pores are small, round openings that form a sponge-like layer on the underside of the cap. Mushrooms with pores, like boletes and polypores, belong to different orders and often have a more robust, fleshy appearance.

To identify whether a mushroom has gills or pores, carefully examine the underside of the cap. Gills are easily recognizable due to their papery or fleshy texture and their arrangement in parallel rows. They can vary in color, thickness, and spacing, which are important characteristics for species identification. For example, the gills of an Amanita mushroom are often white and closely spaced, while those of a shiitake mushroom are tan and more widely spaced. On the other hand, pores appear as a dense network of tiny holes, similar to the surface of a kitchen sponge. When pressed, spores from pored mushrooms may leave a dusty residue or create a distinct pattern on paper, known as a spore print.

The presence of gills or pores is not just a physical trait but also reflects the mushroom’s evolutionary adaptations. Gills maximize surface area for spore dispersal, allowing wind and insects to carry spores more efficiently. Pores, however, provide a more protected environment for spore development, often resulting in larger spore sizes. This distinction is fundamental in mycology, as it helps classify mushrooms into different families and genera. For instance, the Boletaceae family is characterized by its pored mushrooms, while the Amanitaceae family features gilled species.

When identifying mushrooms in the wild, it’s essential to observe the underside closely, as gills and pores can be subtle in young specimens. Gently lift the cap to expose the spore-bearing surface, and note its texture, color, and arrangement. For beginners, creating a spore print can be a helpful technique: place the cap on a piece of paper or glass overnight, and the spores will drop, revealing their color and structure. Gills typically produce a fine, powdery print, while pores yield a more granular or speckled pattern.

In summary, distinguishing between gills and pores is a key step in mushroom identification. Gills are thin, blade-like structures arranged in rows, while pores are small, round openings forming a sponge-like layer. Both serve the same purpose—spore release—but their differences in structure and appearance provide valuable clues about the mushroom’s taxonomy and habitat. By mastering this distinction, you’ll be better equipped to explore the diverse world of fungi with confidence and accuracy.

Exploring the Top Psilocybin Mushrooms for Mind-Altering Experiences

You may want to see also

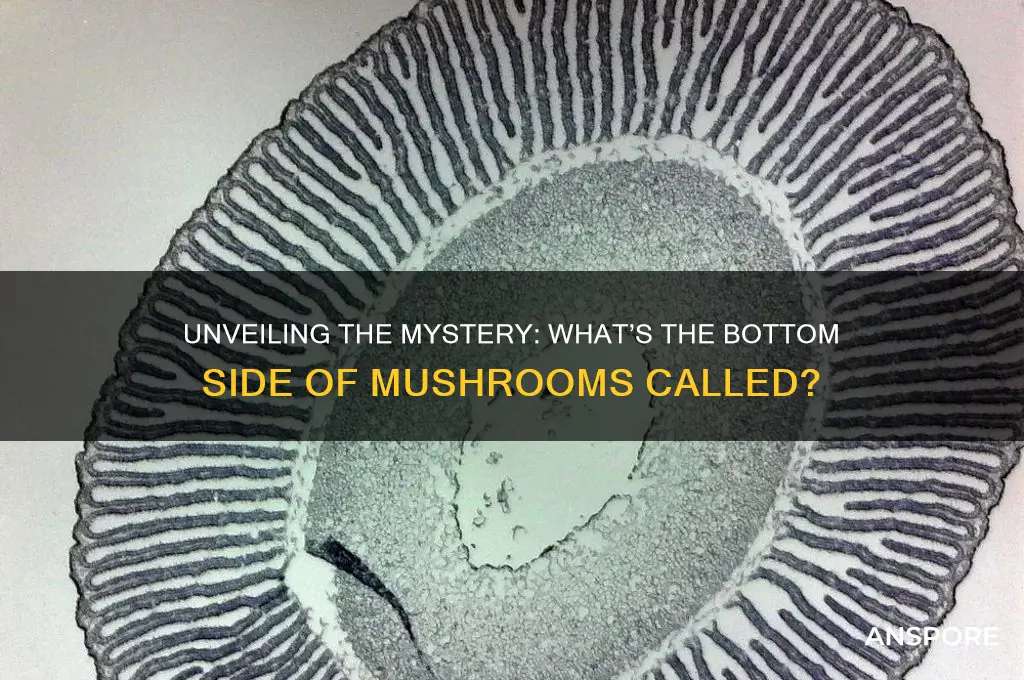

Technical Term Hymenium: The spore-bearing surface on the bottom side of mushrooms

The technical term hymenium refers to the spore-bearing surface located on the underside of mushrooms. This structure is a critical component of fungal reproduction, as it is responsible for producing and dispersing spores, which are the primary means by which fungi propagate. The hymenium is typically found on the gills, tubes, or pores of mushrooms, depending on the species. For instance, in gilled mushrooms like the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), the hymenium lines the thin, blade-like gills. In contrast, boletes and polypores have their hymenium on tubes or pores, respectively. Understanding the hymenium is essential for identifying mushroom species, as its structure and color often serve as key taxonomic characteristics.

The hymenium is composed of specialized cells called basidia, which are the spore-producing organs in basidiomycetes, the fungal division that includes most mushrooms. Each basidium typically bears four spores, which are externally attached and released into the environment when mature. The arrangement, shape, and size of the basidia and spores within the hymenium are crucial for classification and study. For example, the color of the spores, as seen in a spore print, can help distinguish between similar-looking mushroom species. The hymenium’s development and structure also provide insights into the mushroom’s life cycle and ecological role.

In gilled mushrooms, the hymenium is exposed on the gills, which are thin, radiating structures that maximize surface area for spore production. The gills are attached to the cap (pileus) in various ways, such as being free, adnate (broadly attached), or decurrent (extending down the stem). These attachment patterns are important for identification. In contrast, mushrooms with pores, like boletes, have a hymenium that forms a layer of tube-like structures, with the spores produced internally and released through small openings called pores. Polypores, another group, have a hymenium that forms a porous layer directly on the underside of the cap or on bracket-like structures.

The hymenium’s location and morphology are adapted to the mushroom’s environment and dispersal strategy. For example, gills are common in mushrooms that grow on the ground or decaying wood, where air movement can easily carry spores away. Pores and tubes, on the other hand, are often found in species that grow on trees or in more sheltered environments, where spore release may be more gradual. The hymenium’s efficiency in spore production and dispersal is a key factor in the success of fungal species in their ecosystems.

Studying the hymenium requires careful observation and often the use of a microscope to examine basidia, spores, and other microscopic features. Mycologists (fungi experts) use these details to classify mushrooms and understand their evolutionary relationships. For foragers and enthusiasts, recognizing the hymenium’s characteristics can help differentiate edible species from toxic look-alikes. For example, the white spores of *Amanita* species, produced by their gill hymenia, are a distinguishing feature, though not a guarantee of edibility. In summary, the hymenium is not just the bottom side of a mushroom but a complex, functionally vital structure that defines the mushroom’s role in reproduction and identification.

Mushroom Compote: A Savory, Sweet Delight

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$26.99

$39.99

Stipe Attachment Types: How the stem connects to the bottom side (e.g., central, off-center)

The bottom side of mushrooms, where the gills or pores are located, is called the pileus underside or more specifically, the hymenium. This area is crucial for spore production and dispersal. When discussing how the stem (stipe) connects to this underside, we refer to stipe attachment types. Understanding these types is essential for mushroom identification, as they vary significantly across species. The stipe can attach to the pileus in several distinct ways, each providing clues about the mushroom’s taxonomy and habitat.

One common stipe attachment type is central attachment, where the stem connects directly to the center of the pileus underside. This is often seen in agaric mushrooms, such as the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*). Central attachment results in a symmetrical appearance, with the gills or pores radiating evenly from the point of attachment. This type is straightforward to identify and is characteristic of many edible and well-known mushroom species. It is important to note that central attachment does not always mean the stipe is perfectly centered; slight deviations can occur due to growth conditions.

In contrast, off-center attachment occurs when the stipe connects to the pileus at a point other than the exact center. This type is less common but can be observed in species like the offset knight (*Tricholoma portentosum*). Off-center attachment often leads to an asymmetrical cap, with gills or pores appearing unevenly distributed. This characteristic can be a key identifier for certain mushroom species and may indicate specific ecological adaptations. Foragers and mycologists should pay close attention to this detail, as it can distinguish between similar-looking species.

Another stipe attachment type is lateral attachment, where the stem connects to the side of the pileus rather than the underside. This is typical in species like the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), where the cap appears to grow directly out from the substrate with the stipe off to one side. Lateral attachment is often associated with mushrooms that grow on wood or other vertical surfaces. This type allows the mushroom to maximize its exposure for spore dispersal, even in confined spaces.

Finally, some mushrooms exhibit absent or rudimentary stipes, where the stem is either extremely short or entirely absent. In these cases, the pileus may attach directly to the substrate, as seen in puffballs or some cup fungi. While not a traditional stipe attachment type, this variation highlights the diversity in mushroom morphology. Understanding these exceptions is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of fungal structures and their identification.

In summary, stipe attachment types—whether central, off-center, lateral, or absent—play a significant role in mushroom identification and taxonomy. By closely examining how the stem connects to the pileus underside (the hymenium), foragers and mycologists can gain valuable insights into a mushroom’s species, habitat, and ecological role. Each attachment type reflects unique evolutionary adaptations, making this a fascinating aspect of mycology to explore.

Cleaning Sheepshead Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Edibility and Identification: Why knowing the bottom side is crucial for safe mushroom foraging

The bottom side of mushrooms, often referred to as the underside, hymenium, or spore-bearing surface, plays a pivotal role in identifying mushroom species. This area is where spores are produced and released, and its structure can vary significantly between edible and toxic varieties. For foragers, understanding the anatomy of this region is essential for distinguishing safe mushrooms from dangerous look-alikes. The underside can be composed of gills, pores, teeth, or even a smooth surface, each of which is characteristic of specific mushroom families. For instance, the gills of an Agaricus mushroom (like the common button mushroom) are distinct from the pores of a Boletus mushroom. Misidentifying these features can lead to accidental poisoning, as toxic species like the deadly Amanita often mimic the appearance of edible ones.

One of the most critical aspects of mushroom identification is the gill attachment and color, both of which are found on the underside. Gills can be attached to the stem (adnate), free from it, or notched, and their color can change as the mushroom matures. For example, the edible Oyster mushroom has gills that are decurrent (running down the stem), while the toxic Galerina has gills that are adnate. Similarly, the color of the gills can be a key identifier—the Amanita phalloides, a highly toxic species, has white gills, whereas the edible Agaricus bisporus has pinkish-brown gills in maturity. Ignoring these details can have severe consequences, as many poisonous mushrooms share similar cap colors and shapes with edible ones.

For mushrooms with pores instead of gills, the underside structure is equally vital. Pore size, shape, and color are distinguishing features. For instance, the edible King Bolete has large, white pores that turn yellowish-green with age, while the toxic False Bolete has smaller, pale pores that stain blue when bruised. Additionally, the presence of a partial veil or universal veil remnants on the underside can help identify young mushrooms. These veils often leave behind a ring on the stem or a cup-like structure at the base, which are key identification markers. For example, the edible Amanita caesarea has a distinct volva (cup) at its base, while its toxic cousin, Amanita ocreata, has a similar but less pronounced structure.

Another important feature of the mushroom underside is its spore print, which is obtained by placing the cap on paper overnight to collect the falling spores. Spore color is a definitive characteristic for many species and can help differentiate between closely related mushrooms. For instance, the spores of edible Coprinus comatus (Shaggy Mane) are black, while those of the toxic Coprinopsis atramentaria are also black but cause severe reactions when consumed with alcohol. Without examining the underside and performing a spore print, foragers risk misidentifying these species based solely on cap appearance.

In conclusion, knowing the bottom side of mushrooms is indispensable for safe foraging. Whether it’s the gill attachment, pore structure, spore color, or veil remnants, these features provide critical clues to a mushroom’s identity. Relying solely on cap characteristics or superficial similarities can lead to dangerous mistakes. Foragers must develop a keen eye for these underside details, consult reliable field guides, and, when in doubt, seek expert advice. The underside is not just a part of the mushroom—it’s the key to unlocking its edibility and ensuring a safe foraging experience.

The Ultimate Guide to Storing Mushroom Syringes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The bottom side of mushrooms, where the spores are produced, is called the gill or pileus underside.

Yes, the gills are the radiating, blade-like structures found on the underside of the mushroom cap, which is the bottom side of the mushroom.

No, not all mushrooms have gills. Some mushrooms have pores, spines, or other structures on their underside instead of gills, depending on the species.